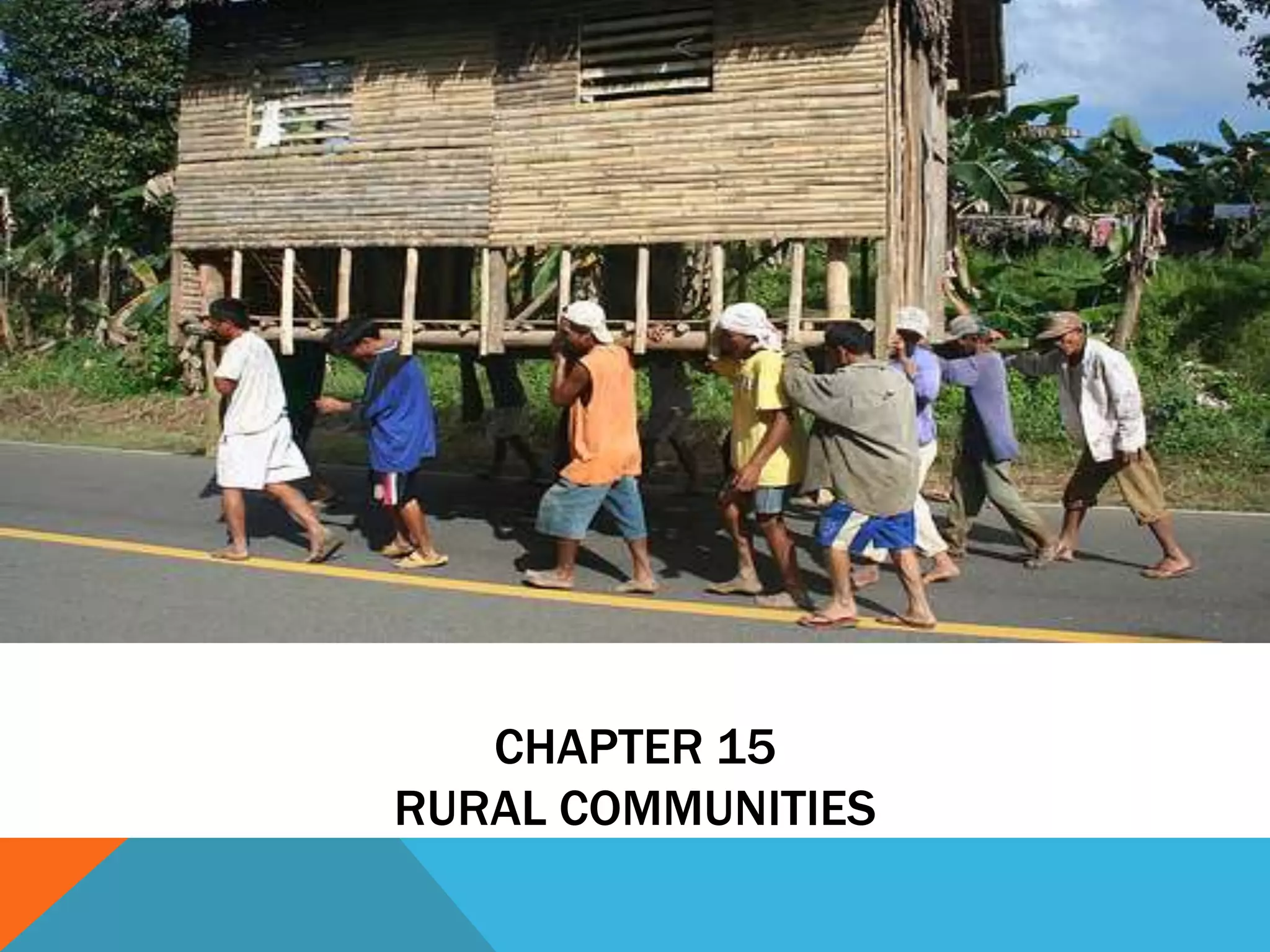

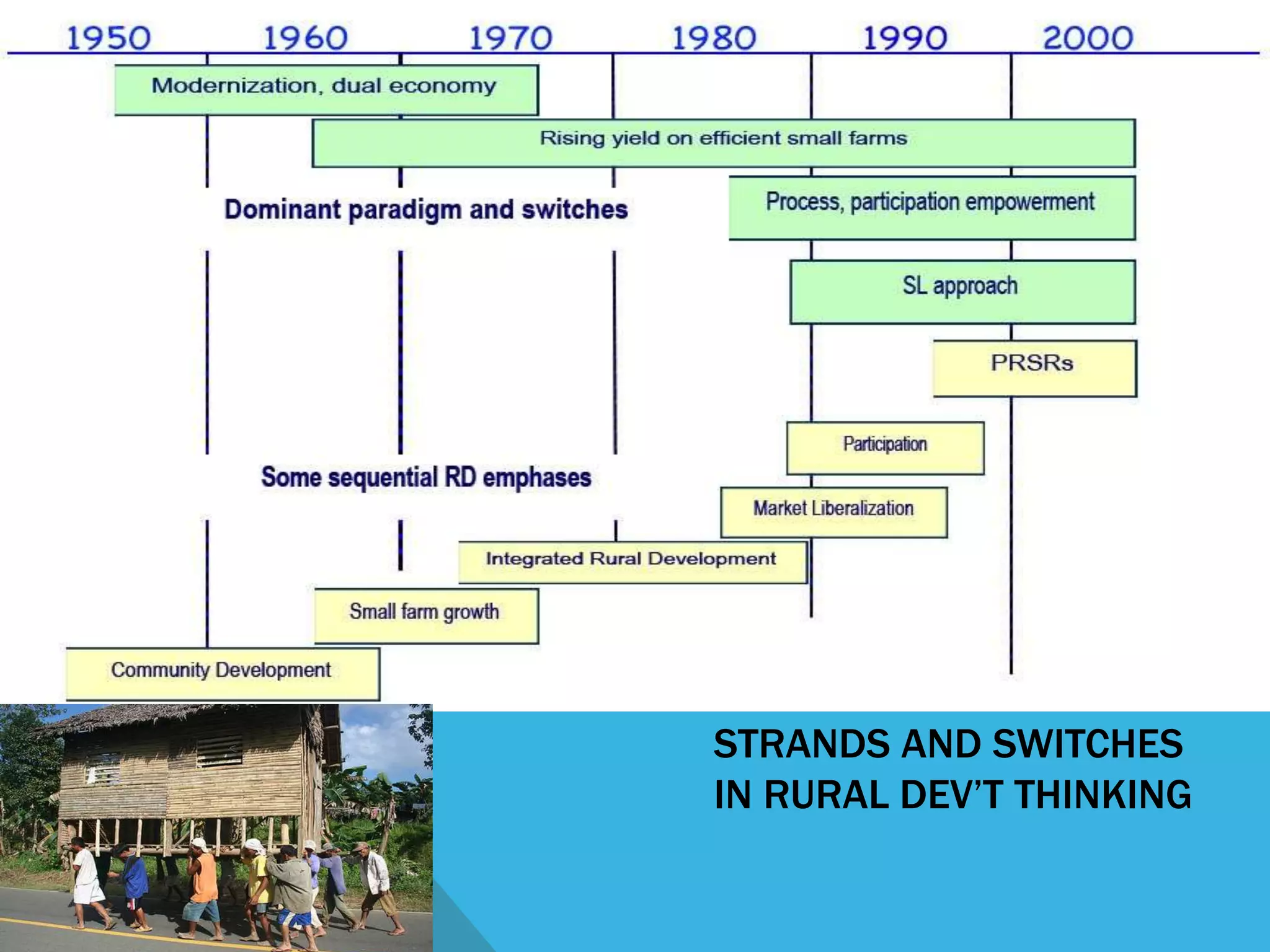

Chapter 15 discusses rural communities, highlighting their characteristics, the role of agriculture, and the development processes affecting them. It emphasizes the importance of self-sustenance and the integration of economic growth with social development in rural areas, as well as the shift in rural development strategies from top-down to participatory approaches. Furthermore, it reflects on governmental policies and the need for cross-sectoral views to effectively reduce rural poverty and improve quality of life.