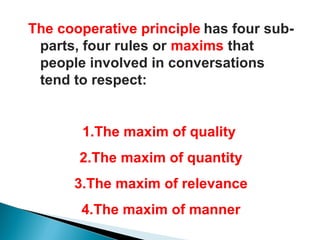

The document summarizes Paul Grice's theory of conversational implicature. It explains that Grice proposed that speaker meaning arises from both sentence meaning and what is implicated based on assumptions of cooperation between conversation participants. Grice's cooperative principle consists of four maxims - quality, quantity, relation, and manner. The document provides examples of how conversational implicatures can arise from observing, violating, or flouting the maxims in context.