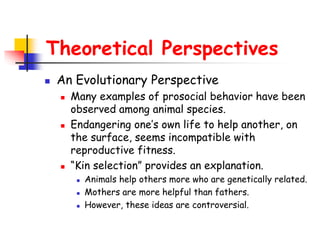

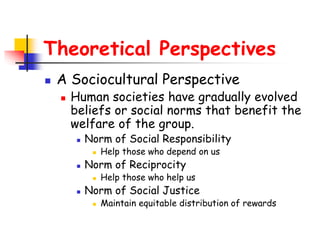

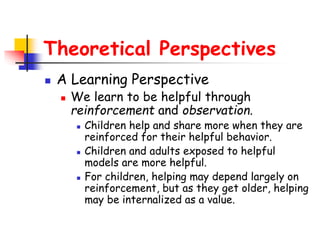

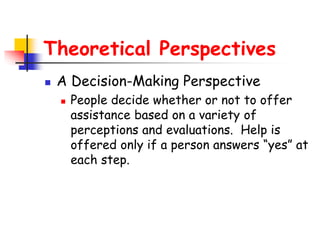

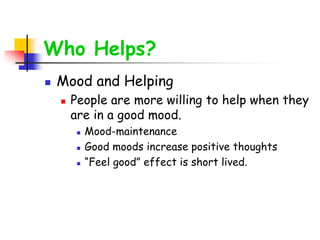

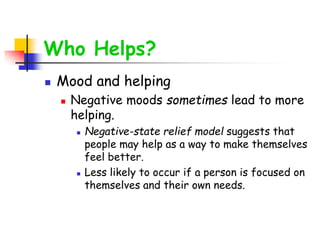

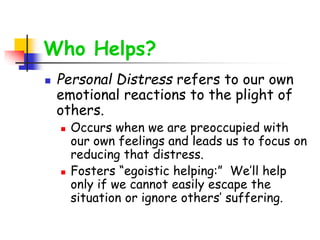

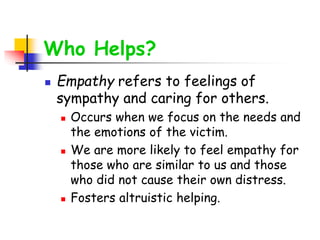

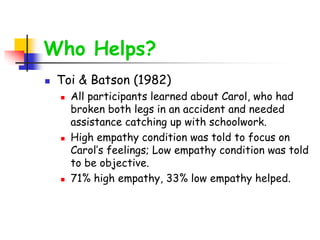

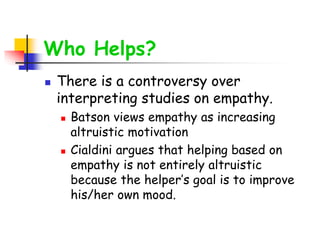

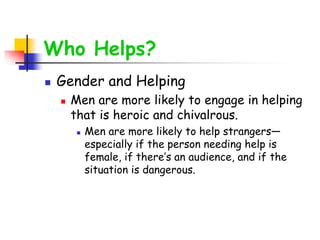

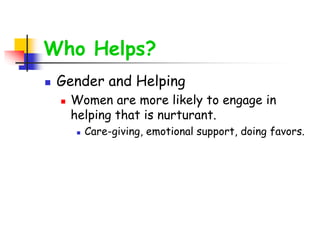

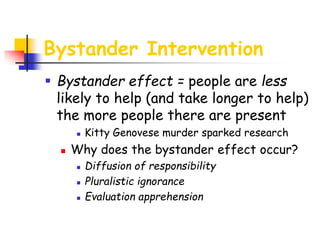

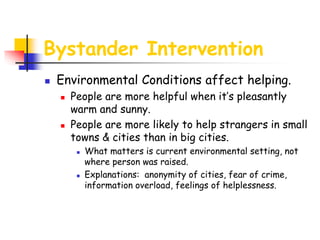

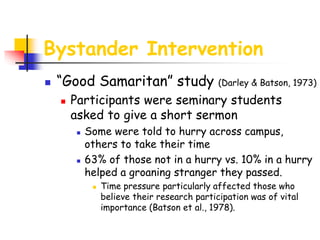

This chapter discusses theories and research on helping behavior and prosocial behavior. It defines key concepts like altruism and prosocial behavior. It outlines four main theoretical perspectives on helping: evolutionary, sociocultural, learning, and decision-making perspectives. It also discusses who helps including the influence of mood, empathy, personality, gender, and environmental factors. Finally, it covers bystander intervention, volunteerism, caregiving, and perspectives on receiving help.