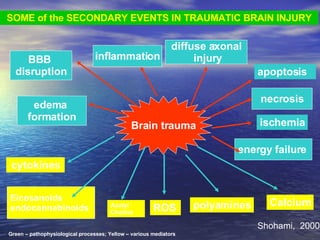

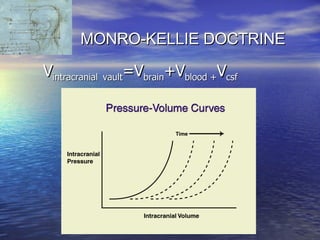

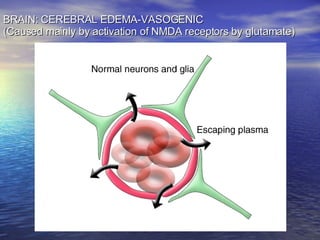

Cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension after traumatic brain injury can be managed through various interventions to control increased intracranial pressure. These include cerebral resuscitation, intracranial pressure monitoring, hyperosmolar therapy with mannitol or hypertonic saline, mild hyperventilation, CSF drainage, temperature control, surgical decompression, and in refractory cases high-dose barbiturates or calcium channel blockers. Nutritional support and anti-seizure prophylaxis may also be considered as part of the management approach.

![INDICATIONS FOR ICP MONITORING IN PATIENTS WITH SEVERE TBI ↑ ICP ≡ ↓ Outcome; Aggressive Tx ≡ ↑ Outcome Intra-cranial pressure monitoring (ICP) is appropriate in all patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Glasgow Coma [GCS] score ≤ 8) The presence of open fontanels and/or sutures in an infant with severe TBI does not preclude the development of intracranial hypertension or negate the utility of ICP monitoring.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cerebral-edema-1216586465240991-8/85/Cerebral-Edema-35-320.jpg)