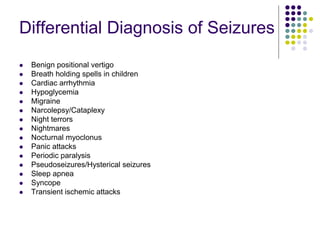

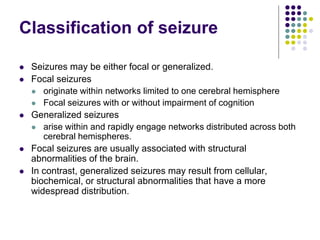

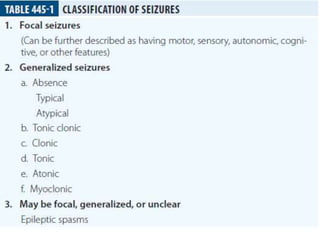

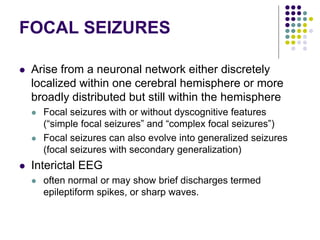

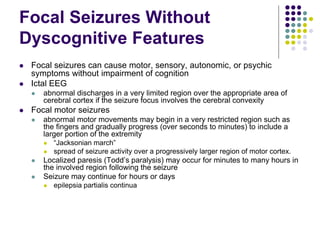

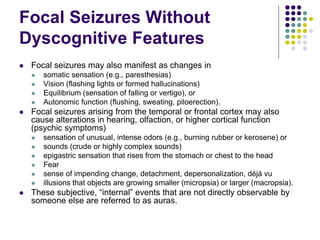

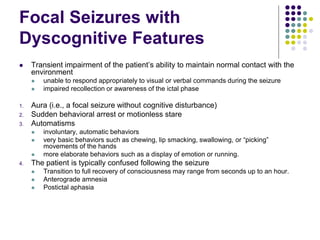

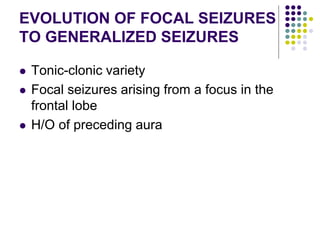

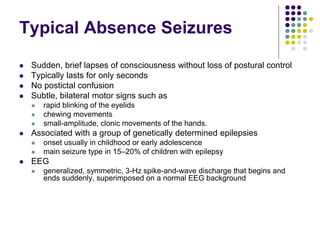

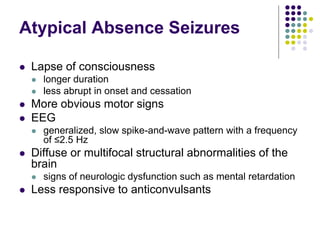

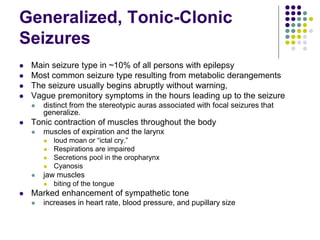

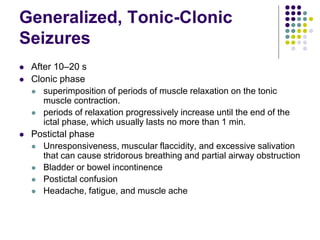

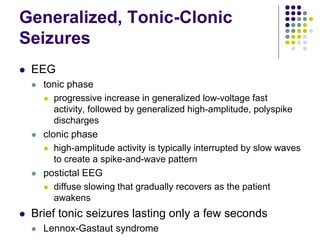

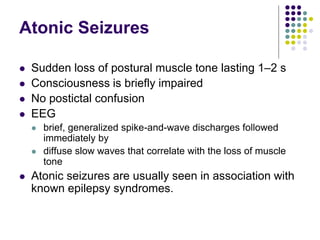

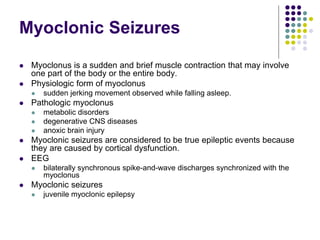

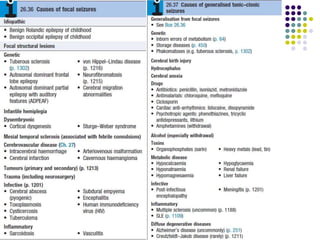

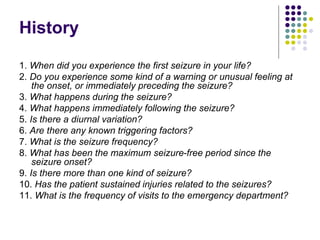

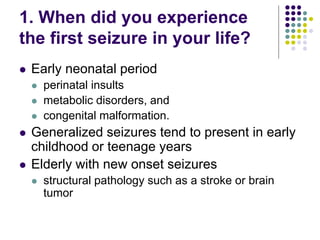

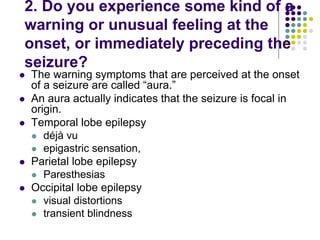

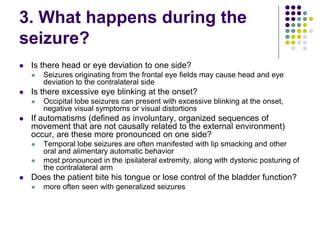

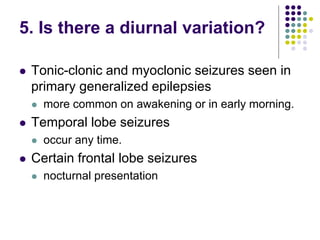

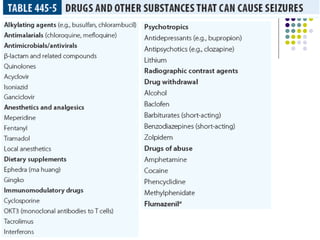

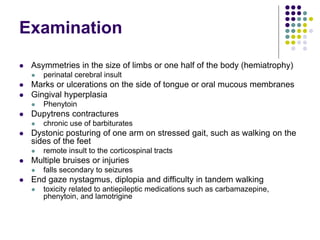

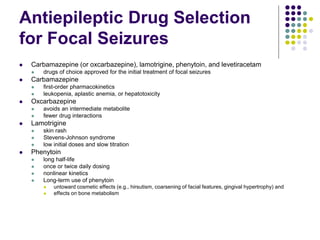

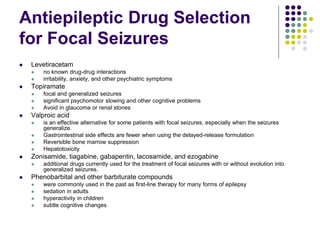

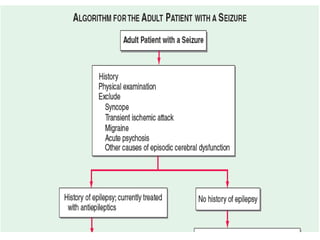

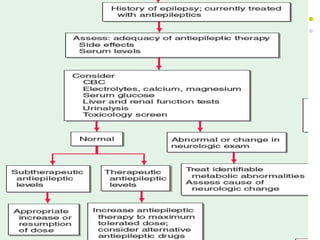

This document provides an overview of approaches to seizure and epilepsy diagnosis and classification. It discusses the differential diagnosis of seizures and conditions that can mimic seizures like syncope. It describes focal seizures which originate in one hemisphere and can involve motor, sensory or cognitive symptoms. Generalized seizures rapidly engage both hemispheres and include absence seizures, tonic-clonic seizures and atonic seizures. Seizures are classified based on their origin and symptoms. The EEG findings for different seizure types are also outlined.