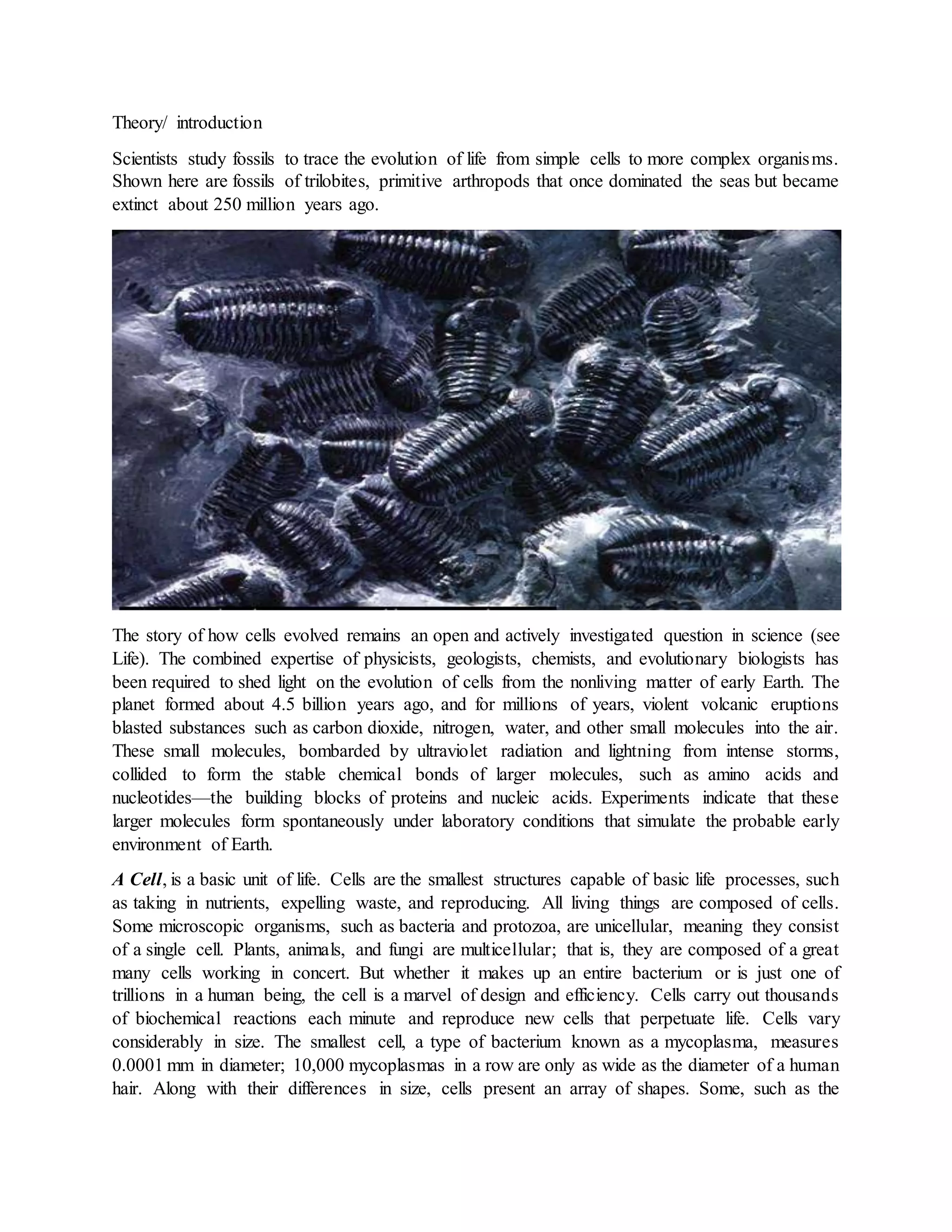

Scientists trace the evolution of life from simple cells to complex organisms by studying fossils. The evolution of cells remains an open question that requires expertise from multiple sciences. Early Earth's atmosphere contained small molecules that collided due to radiation and storms, forming amino acids and nucleotides - the building blocks of proteins and DNA. Cells are the basic units of life that take in nutrients, expel waste, and reproduce, with some consisting of just one cell while others contain many coordinated cells. Cell shape and components are tailored to their functions within multicellular organisms.