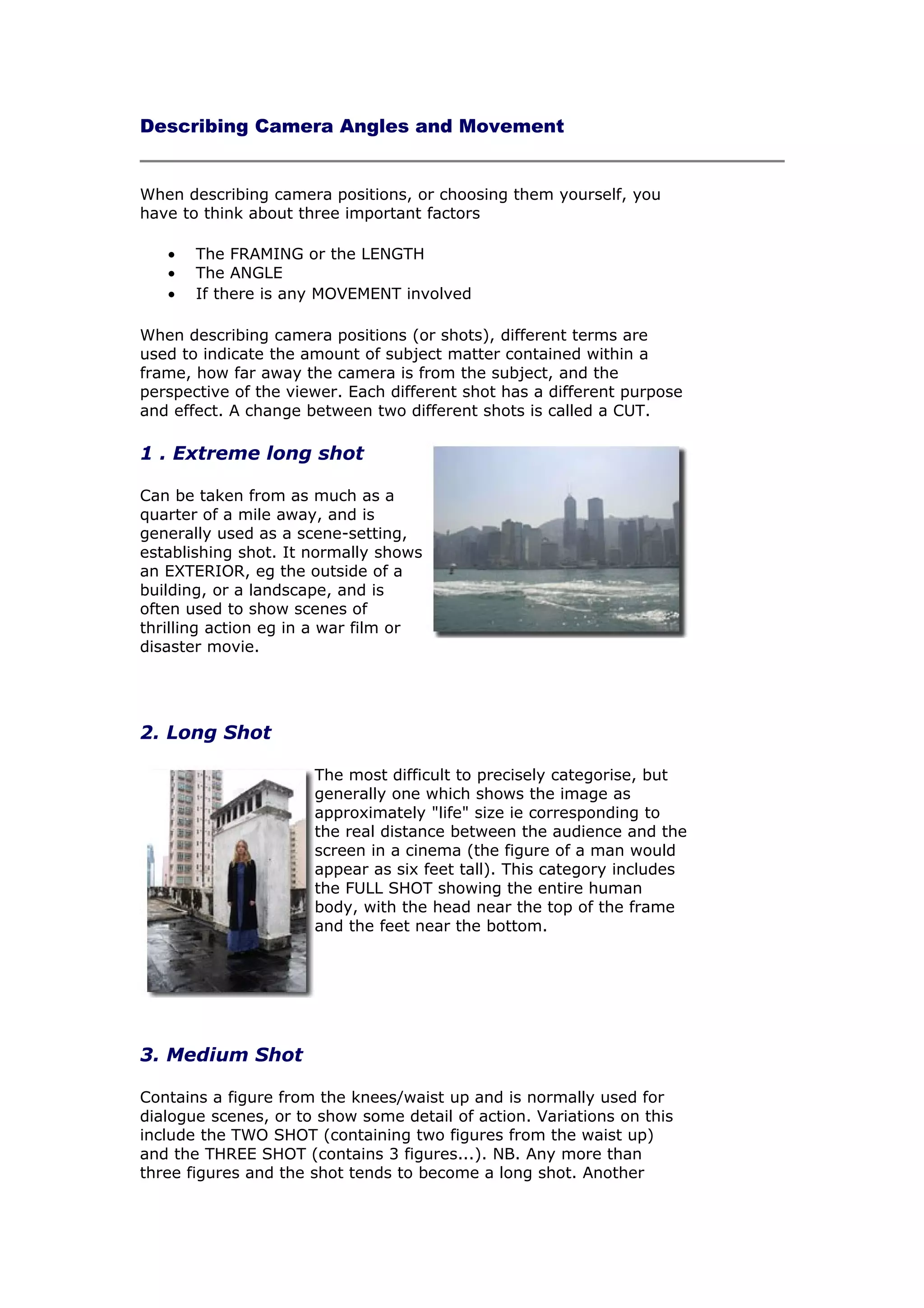

The document describes different camera angles, shots, and movements that are used in filmmaking. It discusses the factors of framing/length, angle, and movement when describing camera positions. It then provides definitions and examples of different shots including extreme long shots, long shots, medium shots, close-ups, and extreme close-ups. It also discusses different camera angles like bird's-eye view, high angle, eye level, low angle, and oblique/canted angle. Finally, it outlines different types of camera movements such as pans, tilts, dolly shots, hand-held shots, crane shots, zoom lenses, and aerial shots.