This document discusses audience research and its importance for organizations that communicate with the public, such as media companies. It provides the following key points:

1. Audience research is a systematic way to estimate audience sizes and discover audience preferences. It is especially important for radio and TV stations that cannot directly count their audiences.

2. Common audience research methods include surveys, observation, people meters, and qualitative research. These methods can be applied to understand audiences for various media like print, internet, arts, and more.

3. Audience, social, and market research share common methods. Understanding audience research provides insights into other types of research.

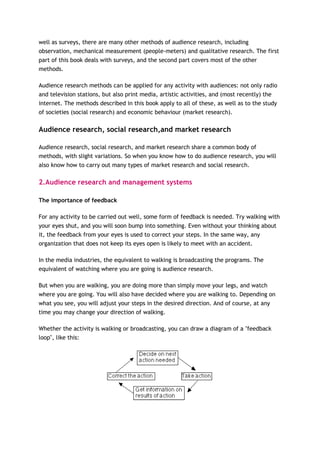

4. Audience research is an important form of feedback that helps organizations understand