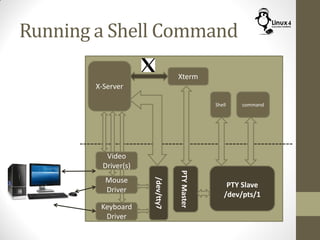

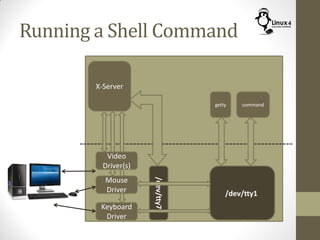

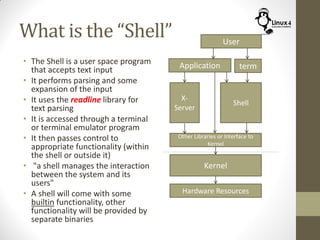

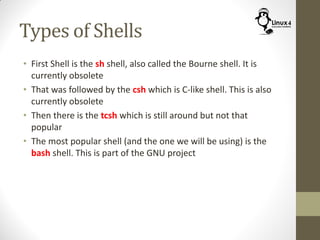

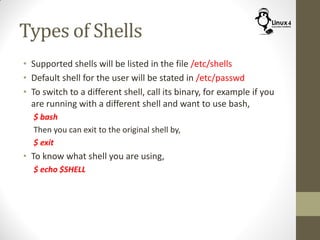

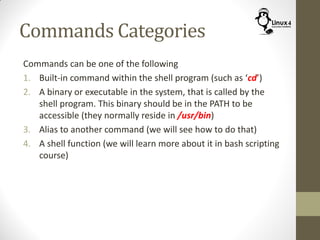

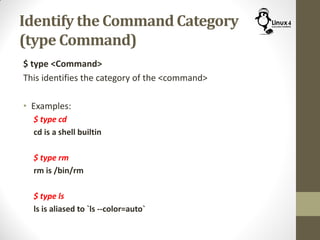

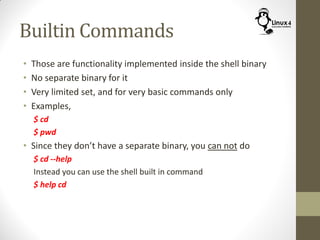

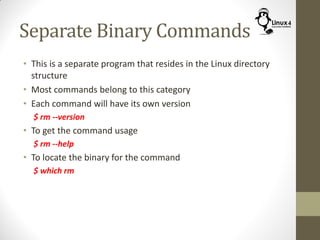

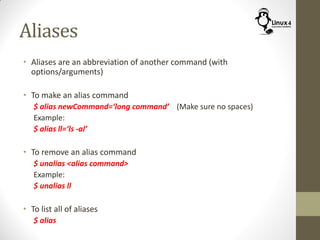

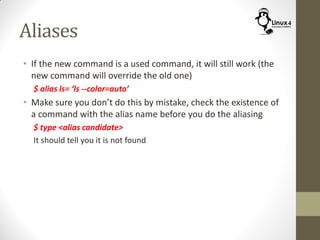

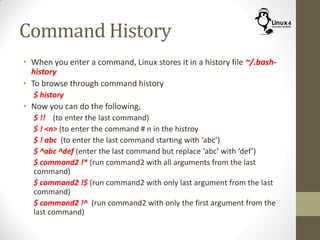

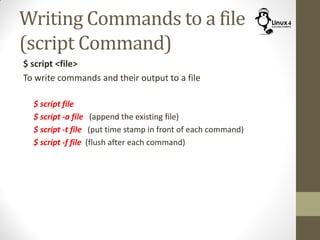

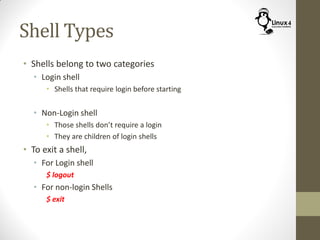

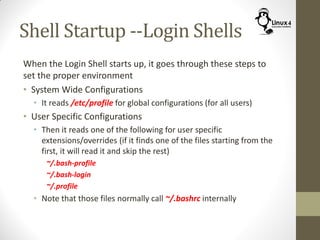

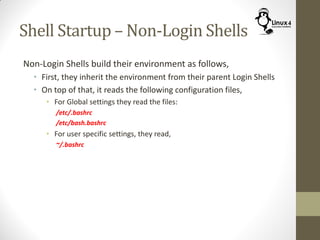

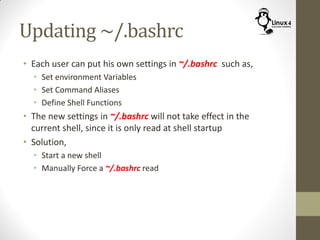

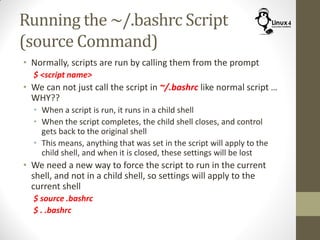

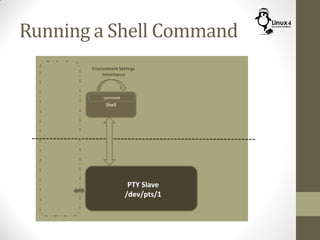

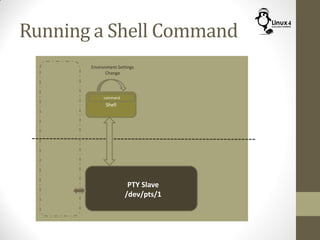

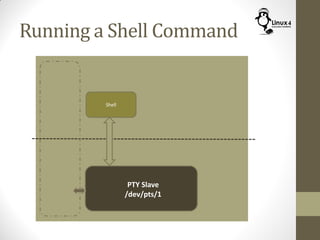

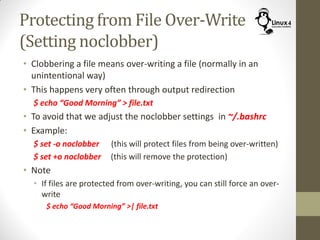

The document is a lecture on the Linux shell for embedded systems, covering the shell's functionality, types, and command categories. It discusses built-in commands, separate binaries, and aliases, as well as shell startup processes for login and non-login shells. Additionally, it provides guidance on writing scripts, updating configuration files, and common settings in the user's .bashrc file.