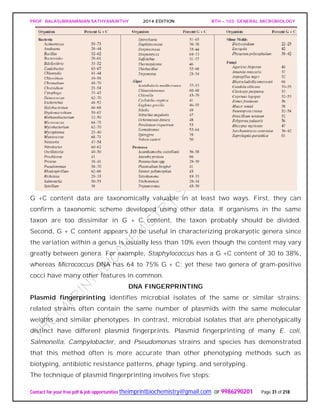

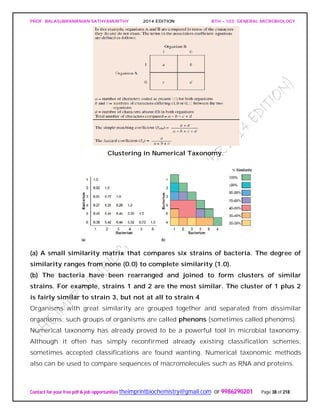

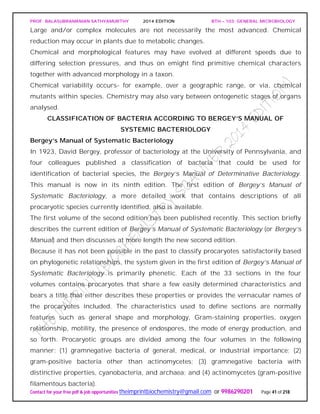

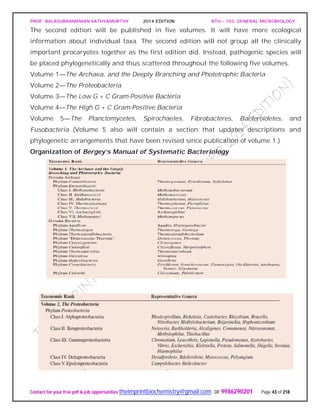

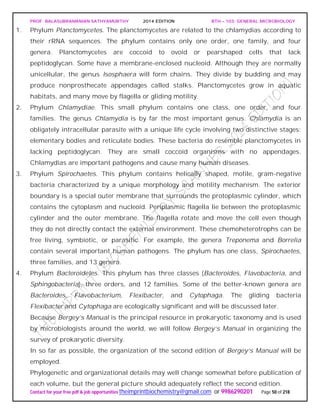

The document discusses microbial classification and taxonomy. It describes the three domain system of classification for microorganisms into Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. It discusses phylogenetic relationships and the endosymbiotic theory of cellular evolution. It also outlines the code for bacterial nomenclature and taxonomy, including the hierarchical taxonomic ranks and criteria for classifying microbes, such as morphological, biochemical, and nucleic acid-based methods.

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

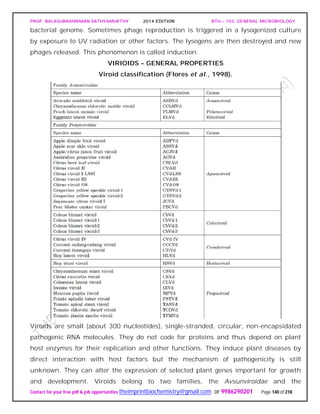

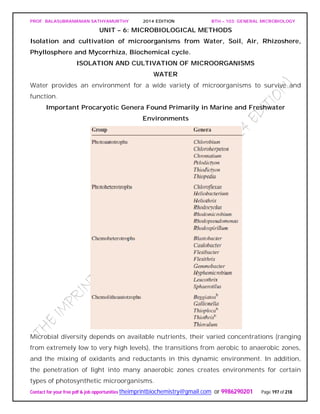

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 15 of 218

PEPTIDOGLYCAN substance present in most gram positive and gram negative

organism.

It has two parts

Glycan: It is made up of N-acetyl glucosomine and N-acetyl muramic acid linked by β-

1,4 glycosidic linkage.

NAG.............NAM [Lactyl ester of NAG]

Peptide: It consists of two parts:

Tetra peptide: It consists of various D and L form of amino acid connected to carboxyl

group of N-acetyl mumaric acid. They are:

Gram negative - L-alanine,D-glutamic acid,diamino pimelic acid,D-alanine.

Peptide linkage:

Peptide linkage is formed between D-alanine and L-lysine (in case of gram +ve) and

diamino primalic acid (in case of gram –ve)

The peptide chain (containing &amino acids) are linked to “NAM” and a peptide chain in

the two side chains.

In gram negative cell wall inter chain peptide linkage is a CO-NH linkage

In the lactyl group because of the free C=0 group (in NAM peptide) chain is attached to

it for example in gram negative cell wall

Peptidoglycan substance present in most gram positive and gram negative organism.

It has two parts

Glycan: It is made up of N-acetyl glucosomine and N-acetyl muramic acid linked by β-

1, 4 glycosidic linkages.

NAG.............NAM [Lactyl ester of NAG]

Peptide: It consists of two parts:

Tetra peptide: It consists of various D and L form of amino acid connected to carboxyl

group of N-acetyl mumaric acid. They are:-

Gram negative - L-alanine, D-glutamic acid, diamino pimelic acid,D-alanine.

Peptide linkage:

Peptide linkage is formed between D-alanine and L-lysine (in case of gram +ve) and

diamino primalic acid (in case of gram –ve)

The peptide chain (containing &amino acids) are linked to “NAM” and a peptide chain in

the two side chains.

In gram negative cell wall inter chain peptide linkage is a CO-NH linkage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-15-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 56 of 218

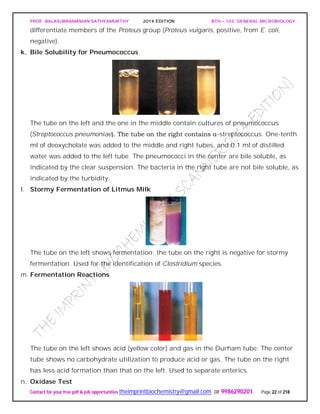

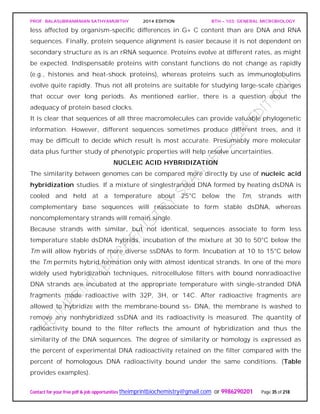

appear to be one. The ordinate in such a dendrogram has no special significance, and

the clusters may be arranged in any convenient order.

The significance of these clusters or phenons in traditional taxonomic terms is not

always evident, and the similarity levels at which clusters are labeled species, genera,

and so on, are a matter of judgment. Sometimes groups are simply called phenons and

preceded by a number showing the similarity level above which they appear (e.g., a 70-

phenon is a phenon with 70% or greater similarity among its constituents). Phenons

formed at about 80% similarity often are equivalent to species.

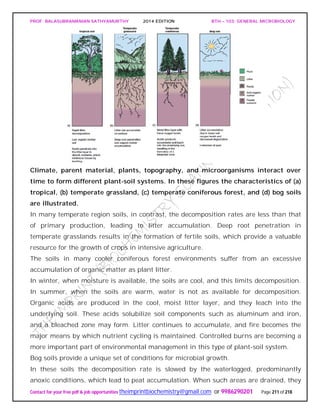

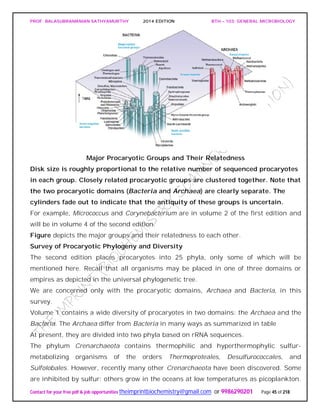

UNIVERSAL PHYLOGENETIC TREE

Following the publication in 1859 of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, biologists began

trying to develop phylogenetic or phyletic classification systems. These are systems

based on evolutionary relationships rather than general resemblance (the term

phylogeny [Greek phylon, tribe or race, and genesis, generation or origin] refers to the

evolutionary development of a species). This has proven difficult for procaryotes and

other microorganisms, primarily because of the lack of a good fossil record. The direct

comparison of genetic material and gene products such as RNA and proteins overcomes

many of these problems.

The studies of Carl Woese and his collaborators on rRNA sequences in procaryotic cells

suggest that procaryotes divided into two distinct groups very early on.

Figure depicts a universal phylogenetic tree that reflects these views. The tree is divided

into three major branches representing the three primary groups: Bacteria, Archaea,

and Eucarya. The archaea and bacteria first diverged, and then the eucaryotes

developed. These three primary groups are called domains and placed above the

phylum and kingdom levels (the traditional kingdoms are distributed among these three

domains). The domains differ markedly from one another.

Eucaryotic organisms with primarily glycerol fatty acyl diester membrane lipids and

eucaryotic rRNA belong to the Eucarya. The domain Bacteria contains procaryotic

cells with bacterial rRNA and membrane lipids that are primarily diacyl glycerol

diesters. Procaryotes having isoprenoid glycerol diether or diglycerol tetraether lipids in

their membranes and archaeal rRNA compose the third domain, Archaea.

It appears likely that modern eucaryotic cells arose from procaryotes about 1.4 billion

years ago. There has been considerable speculation about how eucaryotes might have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-56-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 75 of 218

ACTINOBACTERIA

General Properties of the Actinomycetes

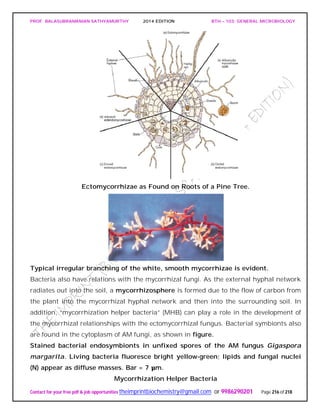

When growing on a solid substratum such as agar, the branching network of hyphae

developed by actinomycetes grows both on the surface of the substratum and into it to

form a substrate mycelium. Septa usually divide the hyphae into long cells (20 μm and

longer) containing several nucleoids. Sometimes a tissuelike mass results and may be

called a thallus. Many actinomycetes also have an aerial mycelium that extends above

the substratum and forms asexual, thin-walled spores called conidia [s., conidium] or

conidiospores on the ends of filaments.

An Actinomycete Colony.

The cross section of an actinomycete colony with living (blue-green) and dead

(white) hyphae. The substrate mycelium and aerial mycelium with chains of

conidiospores are shown.

If the spores are located in a sporangium, they are called sporangiospores. The spores

can vary greatly in shape.

Examples of Actinomycete Spores as Seen in the Scanning Electron Microscope.

Sporulating Saccharopolyspora hyphae (X3,000).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-75-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 81 of 218

that acquires host ATP in exchange for ADP. Thus chlamydiae seem to be energy

parasites that are completely dependent on their hosts for ATP. However, this might not

be the complete story. The complete sequence of the C. trachomatis genome indicates

that the bacterium may be able to synthesize at least some ATP. Although there are two

genes for ATP/ADP translocases, there also are genes for substrate-level

phosphorylation, electron transport, and oxidative phosphorylation.

When supplied with precursors from the host, RBs can synthesize DNA, RNA, glycogen,

lipids, and proteins. Presumably the RBs have porins and active membrane transport

proteins, but little is known about these. They also can synthesize at least some amino

acids and coenzymes. The EBs has minimal metabolic activity and cannot take in ATP

or synthesize proteins. They seem to be dormant forms concerned exclusively with

transmission and infection.

Three chlamydial species are important pathogens of humans and other warm-blooded

animals. C. trachomatis infects humans and mice. In humans it causes trachoma,

nongonococcal urethritis, and other diseases. C. psittaci causes psittacosis in humans.

However, unlike C. trachomatis, it also infects many other animals (e.g., parrots,

turkeys, sheep, cattle, and cats) and invades the intestinal, respiratory, and genital

tracts; the placenta and fetus; the eye; and the synovial fluid of joints.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a common cause of human pneumonia. There is now indirect

evidence that infections by C. pneumonia may be associated with the development of

atherosclerosis and that chlamydial infections may cause severe heart inflammation

and damage. Recently a fourth species, C. pecorum, has been recognized.

SPIROCHAETES

The phylum Spirochaetes [Greek spira, a coil, and chaete, hair] contains gram-negative,

chemoheterotrophic bacteria distinguished by their structure and mechanism of

motility. They are slender, long bacteria (0.1 to 3.0 μm by 5 to 250 μm) with a flexible,

helical shape.

The Spirochetes - Representative examples.

Cristispira sp. from the crystalline style of a clam; phase contrast (X2,200).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-81-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 90 of 218

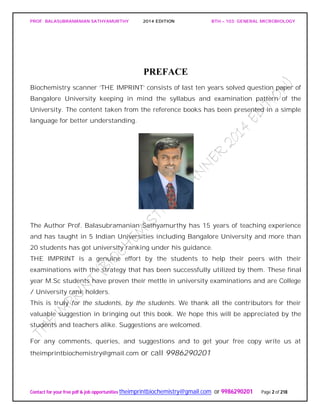

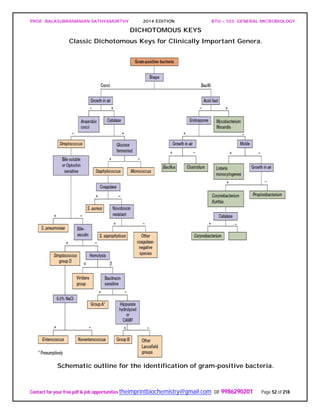

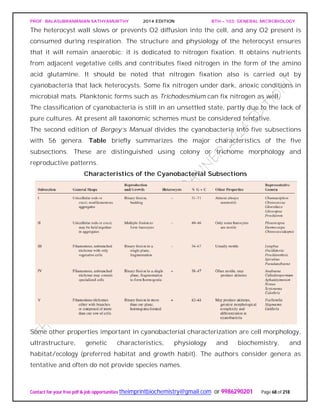

The first edition of Bergey’s Manual divided the archaea into five major groups based on

physiological and morphological differences.

Table summarizes some the characteristics of these five groups and gives

representatives of each.

Characteristics of the Major Archaeal Groups

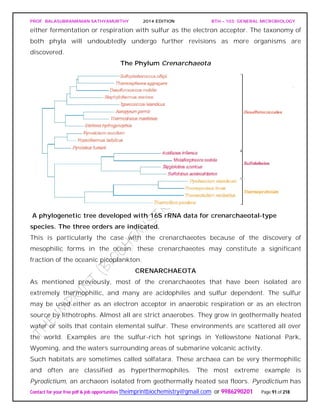

On the basis of rRNA data, the second edition of Bergey’s Manual will divide the

archaea into the phyla Euryarchaeota [Greek eurus, wide, and Greek archaios, ancient

or primitive] and Crenarchaeota [Greek crene, spring or fount, and archaios]. The

euryarchaeotes are given this name because they occupy many different ecological

niches and have a variety of metabolic patterns.

The phylum Euryarchaeota is very diverse with seven classes (Methanobacteria,

Methanococci, Halobacteria, Thermoplasmata, Thermococci, Archaeglobi, and

Methanopyri), nine orders, and 15 families. The methanogens, extreme halophiles,

sulfate reducers, and many extreme thermophiles with sulfur-dependent metabolism

are located in the Euryarchaeota. Methanogens are the dominant physiological group.

The crenarchaeotes are thought to resemble the ancestor of the archaea, and almost all

the well-characterized species are thermophiles or hyperthermophiles. The phylum

Crenarchaeota is divided into one class, Thermoprotei, and three orders. The order

Thermoproteales contains gram-negative anaerobic to facultative, hyperthermophilic

rods. They often grow chemolithoautotrophically by reducing sulfur to hydrogen sulfide.

Members of the order Sulfolobales are coccus-shaped thermoacidophiles. The order

Desulfurococcales contains gramnegative coccoid or disk-shaped hyperthermophiles.

They grow either chemolithotrophically by hydrogen oxidation or organotrophically by](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-90-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 142 of 218

invertebrates, and the prion protein is bound to the surface of neurons. Presumably an

altered PrP is at least partly responsible for the disease.

Despite the isolation of PrP, the mechanism of prion diseases continues to stir

controversy. Most researchers are convinced that prion diseases are transmitted by the

PrP alone. They believe that the infective pathogen is an abnormal PrP (PrPSc; Sc,

scrapieassociated), a protein that has either been changed in conformation or

chemically modified. When PrPSc enters a normal brain, it might bind to the normal

cellular PrP (PrPC) and induce it to fold into the abnormal conformation. The newly

produced PrPSc mo ecule could then convert more normal PrPC proteins to the PrPSc

form. Alternatively, PrPSc could activate enzymes that modify PrP structure. Prions with

different amino acid sequences and conformations convert PrpC molecules to PrPSc in

other hosts.

More support for the “protein-only” hypothesis has been supplied by studies on the

yeast protein Sup35, which aids in the termination of protein synthesis in

Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Because Sup35 acts much like mammalian prions, it has

been called a yeast prion. Sup35 exists in an inactive form in [PSI_] cells, and the

phenotype can be passed on to daughter cells. The inactive, insoluble

form of Sup35 aggregates and translation does not terminate properly. There is

evidence that the [PSI_] phenotype proliferates in yeast when the inactive prion form of

Sup35 interacts with normal, soluble Sup35 and induces a self-propagating

conformational change of active Sup35 to the inactive form.

A minority think that the “protein-only” hypothesis is inadequate. They are concerned

about the existence of prion strains, which they believe are genetic, and about the

problem of how genetic information can be transmitted between hosts by a protein.

Doubters note that proteins have never been known to carry genetic information. It

could be that prions somehow either directly aid an infectious agent such as an

unknown virus or increase susceptibility to the agent. Possibly the real agent is a tiny

nucleic acid that is coated with PrP and interacts with host cells to cause disease. This

hypothesis is consistent with the finding that many strains of the scrapie agent have

been isolated. There is also some evidence that a strain can change or mutate.

Supporters of the “protein-only” hypothesis reply that strain characteristics are simply

due to structural differences in the PrP molecule.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-142-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 148 of 218

water activity or osmotic concentration. For example, Staphylococcus aureus can be

cultured in media containing any sodium chloride concentration up to about 3 M. It is

well adapted for growth on the skin. The yeast Saccharomyces rouxii will grow in sugar

solutions with aw values as low as 0.6. The alga Dunaliella viridis tolerates sodium

chloride concentrations from 1.7 M to a saturated solution. Although a few

microorganisms are truly osmotolerant, most only grow well at water activities around

0.98 (the approximate aw for seawater) or higher. This is why drying food or adding

large quantities of salt and sugar is so effective in preventing food spoilage.

Halophiles have adapted so completely to hypertonic, saline conditions that they

require high levels of sodium chloride to grow, concentrations between about 2.8 M and

saturation (about 6.2 M) for extreme halophilic bacteria. The archaeon Halobacterium

can be isolated from the Dead Sea (a salt lake between Israel and Jordan and the lowest

lake in the world), the Great Salt Lake in Utah, and other aquatic habitats with salt

concentrations approaching saturation. Halobacterium and other extremely halophilic

bacteria have significantly modified the structure of their proteins and membranes

rather than simply increasing the intracellular concentrations of solutes, the approach

used by most osmotolerant microorganisms. These extreme halophiles accumulate

enormous quantities of potassium in order to remain hypertonic to their environment;

the internal potassium concentration may reach 4 to 7 M. The enzymes, ribosomes, and

transport proteins of these bacteria require high levels of potassium for stability and

activity. In addition, the plasma membrane and cell wall of Halobacterium are stabilized

by high concentrations of sodium ion. If the sodium concentration decreases too much,

the wall and plasma membrane literally disintegrate. Extreme halophilic bacteria have

successfully adapted to environmental conditions that would destroy most organisms.

In the process they have become so specialized that they have lost ecological flexibility

and can prosper only in a few extreme habitats.

pH

pH is a measure of the hydrogen ion activity of a solution and is defined as the negative

logarithm of the hydrogen ion concentration (expressed in terms of molarity).

pH = - log [H+] = log(1/[H+])

The pH scale extends from pH 0.0 (1.0 M H+) to pH 14.0 (1.0 X 10-14 M H+), and each

pH unit represents a tenfold change in hydrogen ion concentration.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-148-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 159 of 218

water, glassware, and regular media components often are adequate for growth.

Therefore it is very difficult to demonstrate a micronutrient requirement.

In nature, micronutrients are ubiquitous and probably do not usually limit growth.

Micronutrients are normally a part of enzymes and cofactors, and they aid in the

catalysis of reactions and maintenance of protein structure. For example, zinc (Zn2+) is

present at the active site of some enzymes but is also involved in the association of

regulatory and catalytic subunits in E. coli aspartate carbamoyltransferase.

Manganese (Mn2+) aids many enzymes catalyzing the transfer of phosphate groups.

Molybdenum (Mo2+) is required for nitrogen fixation, and cobalt (Co2+) is a component

of vitamin B12. Electron carriers and enzymes.

Besides the common macroelements and trace elements, microorganisms may have

particular requirements that reflect the special nature of their morphology or

environment.

Diatoms need silicic acid (H4SiO4) to construct their beautiful cell walls of silica

[(SiO2)n]. Although most bacteria do not require large amounts of sodium, many

bacteria growing in saline lakes and oceans depend on the presence of high

concentrations of sodium ion (Na+).

Finally, it must be emphasized that microorganisms require a balanced mixture of

nutrients. If an essential nutrient is in short supply, microbial growth will be limited

regardless of the concentrations of other nutrients.

Requirements for Carbon, Hydrogen, and Oxygen

The requirements for carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen often are satisfied together. Carbon

is needed for the skeleton or backbone of all organic molecules, and molecules serving

as carbon sources normally also contribute both oxygen and hydrogen atoms. They are

the source of all three elements. Because these organic nutrients are almost always

reduced and have electrons that they can donate to other molecules, they also can serve

as energy sources.

Indeed, the more reduced organic molecules are, the higher their energy content (e.g.,

lipids have higher energy content than carbohydrates). This is because, as we shall see

later, electron transfers release energy when the electrons move from reduced donors

with more negative reduction potentials to oxidized electron acceptors with more

positive potentials. Thus carbon sources frequently also serve as energy sources,

although they don’t have to.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-159-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 195 of 218

chloride when added to water and disinfects it in about a half hour. It is frequently used

by campers lacking access to uncontaminated drinking water.

Chlorine solutions make very effective laboratory and household disinfectants. An

excellent disinfectant-detergent combination can be prepared if a 1/100 dilution of

household bleach (e.g., 1.3 fl oz of Clorox or Purex bleach in 1 gal or 10 ml/liter) is

combined with sufficient nonionic detergent (about 1 oz/gal or 7.8 ml/liter) to give a

0.8% detergent concentration. This mixture will remove both dirt and bacteria.

ALCOHOLS

Alcohols are among the most widely used disinfectants and antiseptics. They are

bactericidal and fungicidal but not sporicidal; some lipid-containing viruses are also

destroyed. The two most popular alcohol germicides are ethanol and isopropanol,

usually used in about 70 to 80% concentration. They act by denaturing proteins and

possibly by dissolving membrane lipids. A 10 to 15 minute soaking is sufficient to

disinfect thermometers and small instruments.

QUATERNARY AMMONIUM COMPOUNDS

Detergents [Latin detergere, to wipe off or away] are organic molecules that serve as

wetting agents and emulsifiers because they have both polar hydrophilic and nonpolar

hydrophobic ends. Due to their amphipathic nature, detergents solubilize otherwise

insoluble residues and are very effective cleansing agents. They are different than

soaps, which are derived from fats. Although anionic detergents have some

antimicrobial properties, only cationic detergents are effective disinfectants.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-195-320.jpg)

![PROF. BALASUBRAMANIAN SATHYAMURTHY 2014 EDITION BTH – 103: GENERAL MICROBIOLOGY

Contact for your free pdf & job opportunities theimprintbiochemistry@gmail.com or 9986290201 Page 205 of 218

depths are given in meters and “stacked” Empire State Buildings for perspective.

Light penetrates only into a relatively shallow surface layer, creating the photic

zone.

A series of pressure relationships is observed among the bacteria growing in this

vertically differentiated system. Some bacteria are barotolerant and grow between 0 and

400 atm, but best at normal atmospheric pressure. Many other bacteria are barophiles

[Greek, baro, weight and philein, to love] and prefer higher pressures. Moderate

barophiles grow optimally at 400 atm, but still grow at 1 atm; extreme barophiles grow

only at higher pressures. Pressure differences influence many biological processes

including cell division, flagellar assembly, DNA replication, membrane transport, and

protein synthesis. Porins, outer membrane proteins that form channels for diffusion of

materials into the periplasm, also function most effectively at specific pressures.

Most nutrient cycling in oceans occurs in the top 300 meters where light penetrates.

Light allows phytoplankton to grow and fall as a “marine snow” to the seabed. This

“trip” can take a month or longer. Most of the organic matter that falls below the 300

meter zone is decomposed, and only 1% of photosynthetically derived material reaches

the deep-sea floor unaltered. Because low inputs of organic matter occur in the deep

sea, the ability of microorganisms to grow under oligotrophic conditions becomes

important.

Freshwater Environments

Most fresh water that is not locked up in ice sheets, glaciers, or groundwaters is found

in lakes and rivers. These provide microbial environments that are different from the

larger oceanic systems in many important ways. For example, in lakes, mixing and

water exchange can be limited. This creates vertical gradients over much shorter

distances. Changes in rivers occur over distance and/or time as water flows through

river channels.

Lakes

Lakes vary in nutrient status. Some are oligotrophic or nutrient poor, others are

eutrophic or nutrient-rich.(figureb).

Nutrient-poor lakes remain aerobic throughout the year, and seasonal temperature

shifts do not result in distinct oxygen stratification. In contrast, nutrient-rich lakes

usually have bottom sediments that contain organic matter. In thermally stratified lakes

the epilimnion (warm, upper layer) is aerobic, while the hypolimnion (deeper, colder,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bth103generalmicrobiology-190421182551/85/Bth-103-general-microbiology-205-320.jpg)