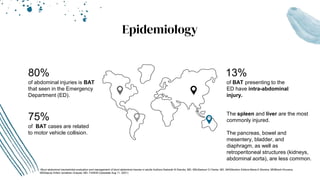

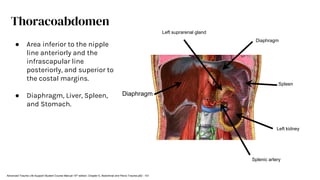

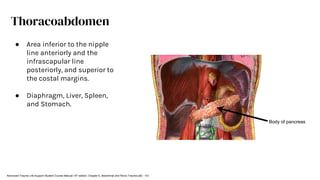

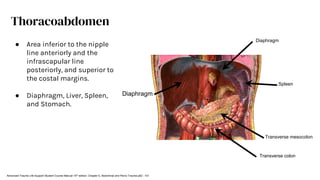

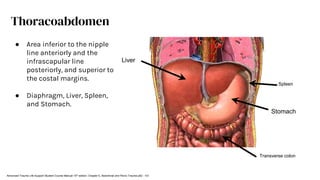

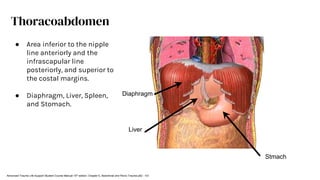

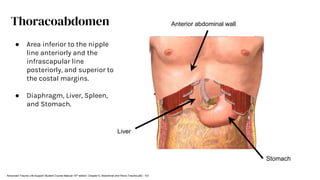

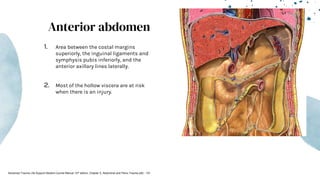

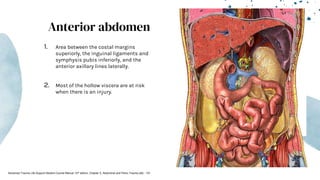

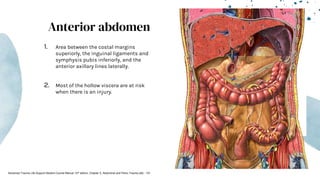

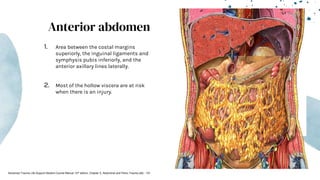

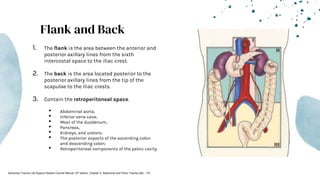

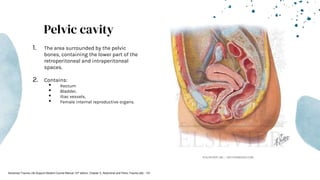

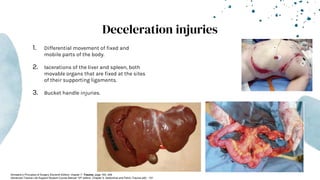

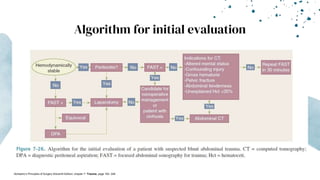

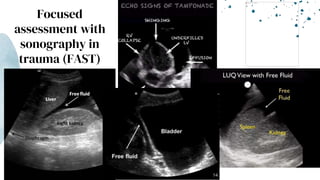

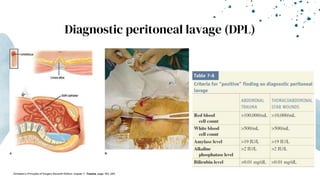

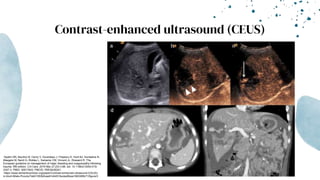

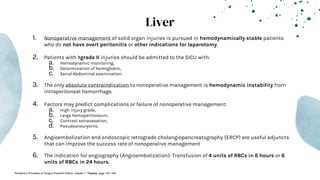

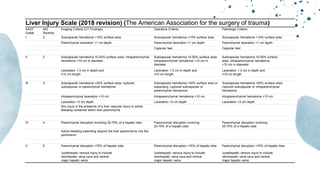

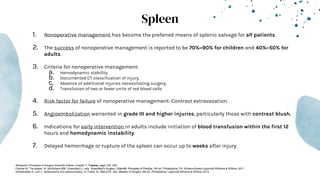

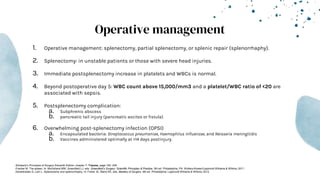

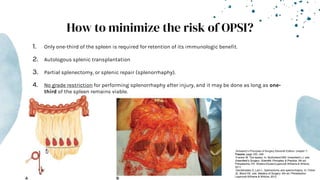

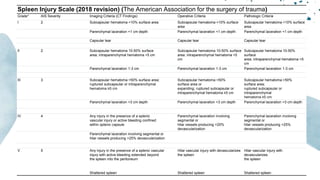

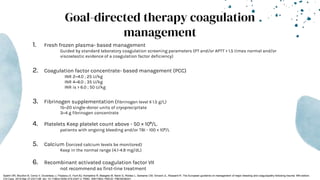

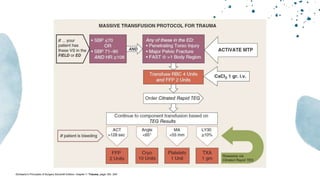

The document outlines blunt abdominal trauma (BAT), focusing on its epidemiology, anatomy, pathophysiologic mechanisms, and management strategies. It highlights that 75% of BAT cases occur due to motor vehicle collisions, with the spleen and liver being the most commonly injured organs, and provides guidelines for nonoperative management of solid organ injuries. Key evaluation techniques such as focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) and the liver and spleen injury scales are also outlined to aid in clinical decision-making.