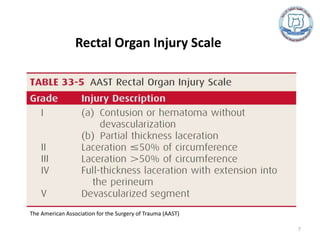

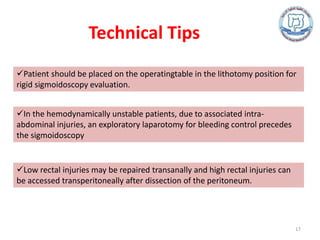

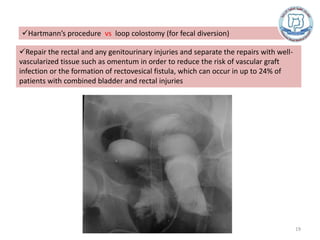

The rectum receives its blood supply from three arteries. Rectal trauma is usually caused by penetrating injuries like gunshot or stab wounds, though blunt trauma from pelvic fractures can also cause injury. Diagnosis involves a digital rectal exam, proctosigmoidoscopy, and CT scan. Intraperitoneal injuries are managed like colon injuries with primary repair. Management of extraperitoneal injuries has evolved from routinely using colostomy, presacral drainage, and rectal washout, though new evidence questions the value of routine presacral drainage and rectal washout. Current treatment involves fecal diversion or primary repair depending on the injury, with presacral drainage only used for posterior injuries repaired via laparotomy