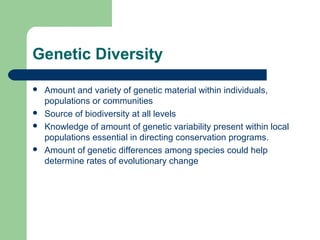

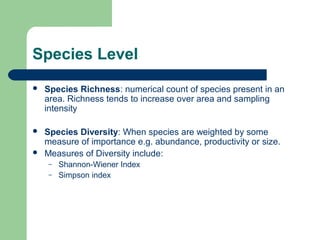

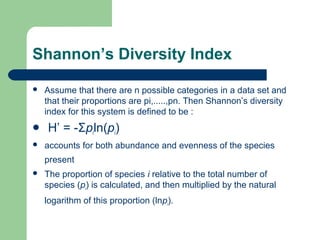

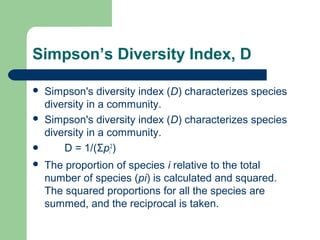

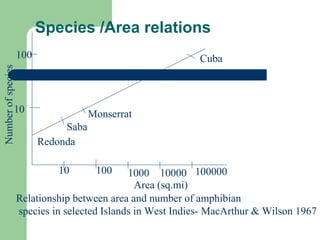

This document discusses biodiversity, including its definition, importance, levels, threats, and patterns. It defines biodiversity as the variety of organisms within an ecosystem and notes it involves more than just species counts. It outlines how biodiversity benefits the global economy through agriculture, recreation, and trade. It then describes the three main levels of biodiversity - genetic, species, and ecosystem diversity. The document also discusses threats like habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, and climate change. It notes patterns involving vulnerable species groups like rare, long-lived, and keystone species. Finally, it contrasts conservation with preservation approaches to biodiversity management.