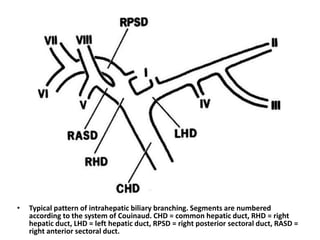

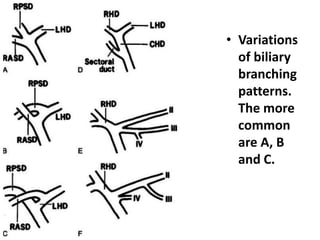

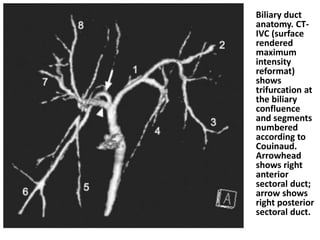

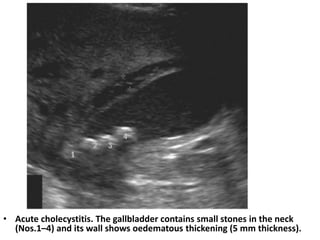

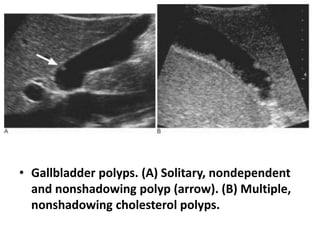

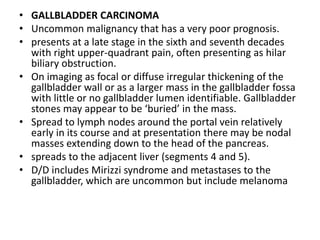

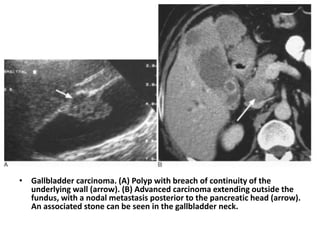

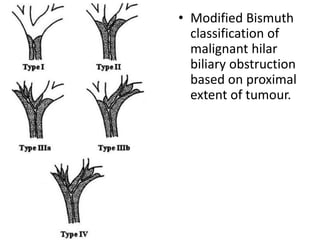

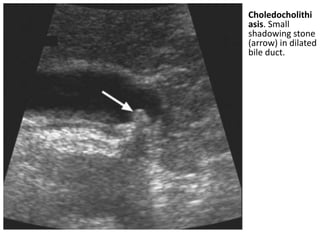

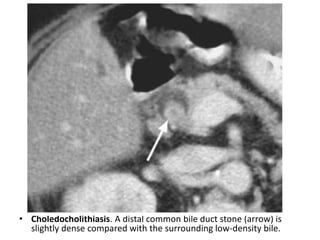

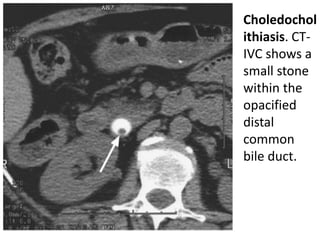

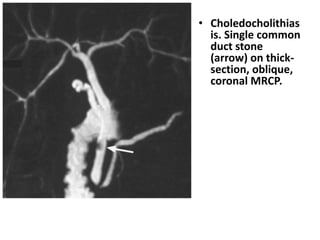

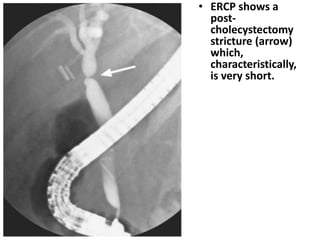

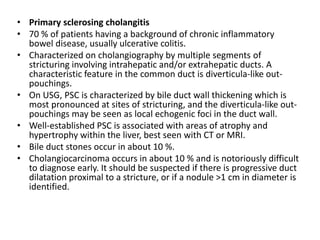

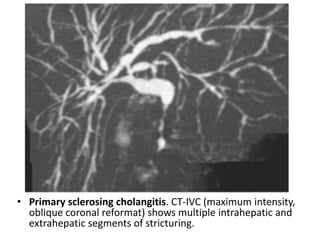

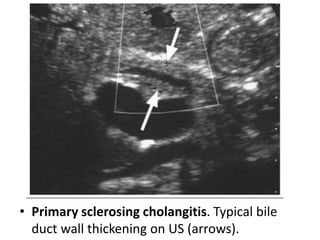

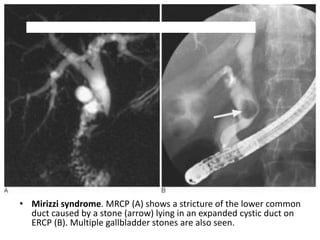

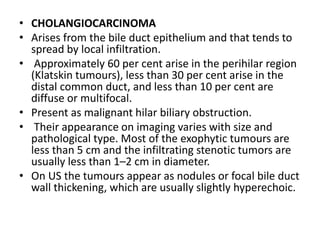

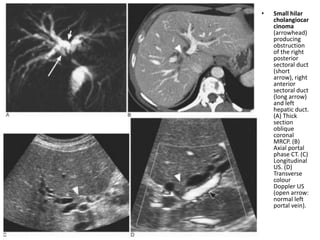

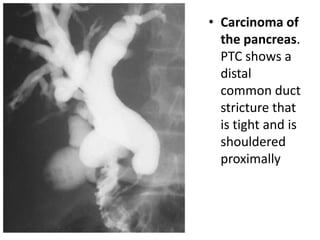

This document discusses biliary pathologies and gallbladder diseases. It describes the typical anatomy of the biliary system and variations. Common gallbladder diseases are discussed such as cholecystitis, gallbladder polyps, and gallbladder carcinoma. Causes of biliary obstruction like choledocholithiasis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Mirizzi syndrome, and cholangiocarcinoma are summarized along with their imaging appearances on ultrasound, CT, and MRCP.