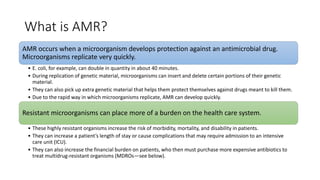

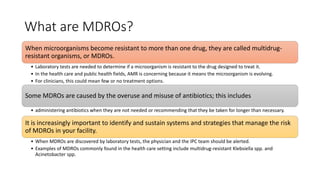

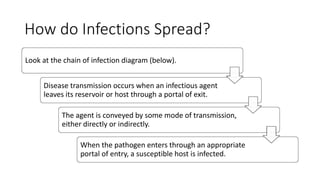

This document provides an overview of microbiology, highlighting the importance of microbes, their classification, and role in human health and disease. It discusses various types of microorganisms, how infections occur and are diagnosed, and the treatment options available, including antibiotics and the issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The document emphasizes the significance of infection prevention and control (IPC) in managing healthcare-associated infections and ensuring effective interventions in health facilities.