The document details a multi-day workshop on spacecraft RF communication, covering topics such as RF signal transmission, modulation techniques (like BPSK and QPSK), telemetry systems, and error control coding. It emphasizes the significance of channel coding for long-distance communication, using examples like the Voyager mission, and discusses various signal processing techniques. Key concepts include Doppler effects, time dilation, link budgets, and advanced decoding methods like turbo decoding.

![Error Control and Channel Coding

Time Diversity:

After receiver reassembles,

all errors can be corrected

See [R5] and [R6]

10/30/2013

© John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-11-320.jpg)

![Error Control and Channel Coding

Concatenated coding for Voyager mission to Saturn and Uranus

Power efficiency is extremely important: Coding gain of 6dB can double the

communications range between spacecraft and earth ([C8], page 172)

Voyager telecommunications achieved 10-6 BER at EbN0 = 2.53dB, 2Mbits/sec.

What system considerations are not very important?

Bandwidth efficiency, not many other users out there.

Delay, waiting time for image reconstructions is OK

10/30/2013

© John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-15-320.jpg)

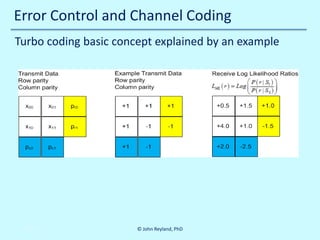

![Error Control and Channel Coding

Log likelihood ratio of modulo two addition of two soft decisions (see []):

(

L ( r0 ⊕ r1 ) L ( r0= sig nL ( r0 ) ) sig nL ( r1 ) ) min L ( r0 ) , L ( r1 )

=

) L ( r1 )

(

(

)

This addition rule is used to combine data and parity into extrinsic information

Extrinsic means extra, or indirect, information derived from the decoding process

10/30/2013

© John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-18-320.jpg)

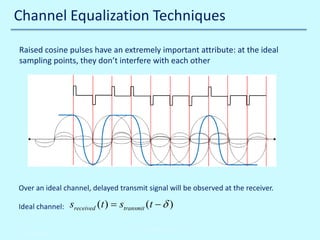

![Channel Equalization Techniques

A decision feedback

nonlinear adaptive

equalizer:

See [E1] and [E2]

10/30/2013

© John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-24-320.jpg)

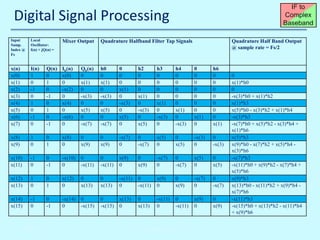

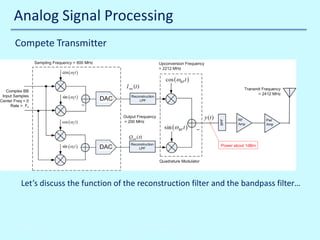

![Digital Signal Processing

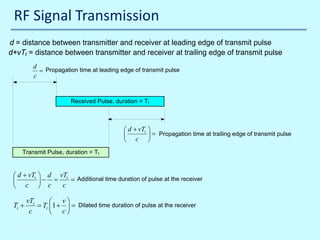

Intermediate center frequency Fif = 44.2368 MHz.

Does this mean sampling frequency Fs > 88.4736 MHz ?

No, we can bandpass sample, by making Fs = (4/3) Fif = 58.9824 MHz. This has advantages:

• Lower sample rate => smaller sample buffers and fewer FPGA timing problems

• Fif can be higher for the same sample rate, this may make frequency planning easier

Disadvantage is that noise in the range [Fs/2 Fs] is folded back into [0 Fs/2]

10/30/2013

John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-30-320.jpg)

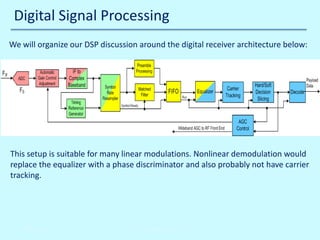

![Digital Signal Processing

Halfband Filter response

HalfBand filter Impulse Response, Order=11

0.6

0.4

Typical Matlab code:

0.2

0

-0.2

Fss = 58.9824e6;

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Resp, dB

0

-10

-20

-30

-40

0

3.6864

7.3728

11.0592 14.7456 18.432

Frequency (MHz)

22.1184 25.8048 29.4912

0

3.6864

7.3728

11.0592 14.7456 18.432

Frequency (MHz)

22.1184 25.8048 29.4912

Resp, linear

1

0.5

0

10/30/2013

John Reyland, PhD

% Setup halfband filter for input subsampling

PassBandEdge = 1/2-1/8;

StopBandRipple = 0.1;

b=firhalfband('minorder', …

PassBandEdge, …

StopBandRipple, …

'kaiser');

% Check frequency response

[hb,wb] = freqz(b,1,2048);

plot(wb,10*log10(abs(hb)));

set(gca,'XLim',[0 pi]);

set(gca,'XTick',0:pi/8:pi);

set(gca,'XTickLabel',(0:(Fss/16):(Fss/2))/1e6);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-32-320.jpg)

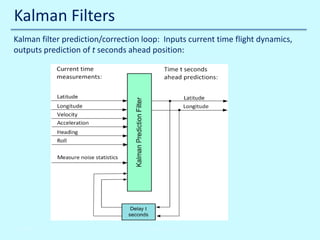

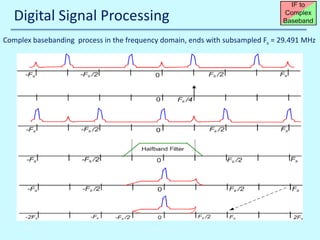

![Digital Signal Processing

DSP Circuits for IF to Complex BB process

Fs/4 Local Oscillator

Inphase Halfband Filter

I(n) + jQ(n) = [1+j0,0+j1,-1+j0,0-j1,1+j0, ...]

HI(z) = h0 + z-2h2 + z-3h3 + z-4h4 + z-6h6

Ib(n)

x(n)

Z-1

h0

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

0

h2

h3

h4

0

h6

Ihb(n)

2

Qb(n)

Z-1

h0

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

Z-1

0

h2

h3

h4

0

h6

Qhb(n)

2

Quadrature Halfband Filter

HQ(z) = h0 + z-2h2 + z-3h3 + z-4h4 + z-6h6

10/30/2013

John Reyland, PhD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atispacecraftrfcommssampleslidesnovember2013-131030105841-phpapp02/85/Spacecraft-RF-Communications-Course-Sampler-33-320.jpg)