This document is the 2018 ASHRAE Handbook: Refrigeration which is copyrighted and for single user use only. It was published by ASHRAE and contains 51 chapters on refrigeration systems and applications. No part of the publication can be reproduced without permission from ASHRAE. Volunteer members of ASHRAE Technical Committees compiled the information which is generally reviewed and updated every four years with comments, criticisms, and suggestions invited.

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

2.1

CHAPTER 2

AMMONIA REFRIGERATION SYSTEMS

EQUIPMENT............................................................................. 2.1

Compressors .............................................................................. 2.1

Condensers................................................................................. 2.5

Evaporators ............................................................................... 2.9

Evaporator Piping ................................................................... 2.10

Vessels...................................................................................... 2.11

Piping....................................................................................... 2.14

Controls.................................................................................... 2.15

SYSTEMS.................................................................................. 2.19

Single-Stage Systems................................................................ 2.19

Economized Systems................................................................. 2.19

Multistage Systems................................................................... 2.19

Liquid Recirculation Systems................................................... 2.21

Safety Considerations............................................................... 2.26

USTOM-ENGINEERED ammonia (R-717) refrigeration sys-

Ctems often have design conditions that span a wide range of

evaporating and condensing temperatures. Examples are (1) a food

freezing plant operating from 10 to –45°C; (2) a candy storage

requiring 15°C db with precise humidity control; (3) a beef chill

room at –2 to –1°Cwith high humidity; (4) a distribution warehouse

requiring multiple temperatures for storing ice cream, frozen food,

meat, and produce and for docks; and (5) a chemical process requir-

ing multiple temperatures ranging from 15 to –50°C. Ammonia is

the refrigerant of choice for many industrial refrigeration systems.

See Chapter 24 for information on refrigeration load calculations.

The figures in this chapter are for illustrative purposes only, and

may not show all the required elements (e.g., valves). For safety

and minimum design criteria for ammonia systems, refer to

ASHRAE Standard 15, IIAR Bulletin 109, IIAR Standard 2, and

applicable state and local codes.

History of Ammonia Refrigeration

First synthesized in 1823, ammonia was first used as a refrigerant

in an ice-making vapor absorption system developed by Ferdinand

Carré, a French engineer and inventor, in 1858 (GPO 1893). The

Carré machine used an aqueous ammonia solution, with water as the

absorbent and ammonia as the refrigerant. This type of vapor absorp-

tion system remains in use today.

Use of ammonia as a refrigerant in vapor compression systems

followed. David Boyle established an ice production plant in Jeffer-

son, TX, in 1873 using an improved compressor design, and he later

set up the Boyle Ice Machine Co. in Chicago, IL, in 1878 (Balmer

2010; Woolrich and Clark n.d.). With the financial backing of sev-

eral breweries, Professor Carl von Linde of Munich, Germany, had

30 ice machines of his design built between 1875 and 1881 (Dincer

1997; Schmidt 1908).

The first commercial production of synthetic ammonia began in

1913 (IIAR n.d.). Worldwide annual production of ammonia is

approximately 135 million metric tons, of which 9.4 million metric

tons was produced in the United States in 2011 (USGS 2012). Over

80% of the ammonia produced is used in agriculture as fertilizer; less

than 2% is used as a refrigerant (ASHRAE 2017).

Of the three primary first-generation refrigerants used during the

1920s [i.e., ammonia (R-717), chloromethane (R-40), and sulfur

dioxide (R-764)], only ammonia remains in use today as a refriger-

ant. Ammonia is considered a natural refrigerant because it is a com-

mon, naturally occurring compound, and it naturally breaks down

into hydrogen and nitrogen.

Ammonia Refrigerant for HVAC Systems

There is renewed interest in using ammonia for HVAC systems,

in part because of the scheduled phaseout and increasing costs of

chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) and hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC)

refrigerants. Ammonia secondary systems that circulate chilled water

or another secondary refrigerant are a viable alternative to halocar-

bon systems, although ammonia is inappropriate for direct refriger-

ation systems (ammonia in the air unit coils) for HVAC applications.

Ammonia packaged chilling units are available for HVAC applica-

tions. As with the installation of any air-conditioning unit, all appli-

cable codes, standards, and insurance requirements must be

followed.

1. EQUIPMENT

1.1 COMPRESSORS

Compressors available for single- and multistage applications in-

clude the following:

• Rotary vane

• Reciprocating

• Rotary screw

Rotaryvanecompressorsaretypicallyusedforlow-stage(booster)

compressor applications. Reciprocating and screw compressors can

be used as single-stage, low-stage (booster), or high-stage machines

and can also be internally compounded to provide multiple compres-

sion stages on one compressor body.

The reciprocating compressor is the most common compressor

used in small, 75 kW or less, single-stage or multistage systems. The

screw compressor is the predominant compressor above 75 kW, in

both single- and multistage systems. Various combinations of com-

pressors may be used in multistage systems. Rotary vane and screw

compressors are frequently used for the low-pressure stage, where

large volumes of gas must be moved. The high-pressure stage may

be a reciprocating or screw compressor.

When selecting a compressor, consider the following:

• System size and capacity requirements.

• Location, such as indoor or outdoor installation at ground level or

on the roof.

• Equipment noise.

• Part- or full-load operation.

• Winter and summer operation.

• Pulldown time required to reduce the temperature to desired con-

ditions for either initial or normal operation. The temperature

must be pulled down frequently for some applications for a pro-

cess load, whereas a large cold-storage warehouse may require

pulldown only once in its lifetime.

Lubricant Cooling. When a reciprocating compressor requires

lubricant cooling, an external heat exchanger using a refrigerant or

secondary cooling is usually added. Screw compressor lubricant

cooling is covered in detail in the section on Screw Compressors.

The preparation of this chapter is assigned to TC 10.3, Refrigerant Piping,

Controls and Accessories.

Related Commercial Resources](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-47-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

2.4 2018 ASHRAE Handbook—Refrigeration (SI)

reciprocating compressors. Most rotary vane compressors are lubri-

cated by injectors because they have no crankcase. In some designs,

a lubricant separator, lubricant receiver, and cooler are required on

the discharge of these compressors; a pump recirculates lubricant to

the compressor for both cooling and lubrication. In other rotary vane

compressor designs, a discharge lubricant separator is not used, and

lubricant collects in the high-stage suction accumulator or inter-

cooler, from which it may be drained. Lubricant for the injectors

must periodically be added to a reservoir.

Cooling. The compressor jacket is cooled by circulating a cool-

ing fluid, such as a water/glycol solution or lubricant. Lubricant is

recommended, because it will not freeze and can serve both pur-

poses (Figure 4).

Screw Compressors

Helical screw compressors are the choice for most industrial re-

frigeration systems. All helical screw compressors have a constant-

volume (displacement) design. The volume index Vi refers to the in-

ternal volume ratio of the compressor (i.e., the reduction in volume

of the compressed gas from suction to discharge of the compressor).

Capacity control is accomplished by use of a slide valve, bypass

ports, or by controlling the speed [variable-frequency drive (VFD)].

The slide valve and bypass ports control capacity by only using a

portion of the screw(s) for the compression process.

Some compressors are designed with a fixed Vi. When Vi is fixed,

the compressor functions most efficiently at a certain compression

ratio (CR). In selecting a fixed Vi compressor, consider the average

CR rather than the maximum CR. A guide to proper compressor

selection is based on the equation Vi

k = CR, where k = 1.4 for ammo-

nia. For example, a screw compressor operating at 265 kPa suction

and 1350 kPa discharge has a CR = 5.09. Therefore, Vi = 3.2 (Vi =

CR1/k). Thus, a compressor with the Vi at or close to 3.2 is the best

selection. Because ambient conditions vary throughout the year, the

average condensing temperature may be 24°C (969 kPa). With the

lower discharge pressure, the average compressor CR is 3.65 and the

ideal Vi is 2.52. Therefore, a compressor with the Vi at or close to 2.5

is the proper selection to optimize efficiency.

Some compressors are equipped with a variable Vi control. This

makes compressor selection simpler, because the volume index can

vary for different operating conditions. Therefore, the internal

compression ratio can automatically match the external pressure

ratio. Typically, screw compressors with variable Vi can control

between 2.2 and 5.0 Vi. Variable-Vi compressors are beneficial over

a wide range of system pressure ratios to improve efficiency as con-

densing pressures vary.

Piping. Oil-flooded screw compressors are the most common

type of screw compressor used in refrigeration. Introduced in the late

1950s as an alternative to dry compressors with a symmetric rotor

profile, oil-flooded compressors rapidly gained acceptance in many

conventional reciprocating and small centrifugal applications. These

compressors typically have oil supplied to the compression area at a

volume rate of about 0.5% of the displacement volume. Some of this

oil is used for lubricating the bearings and shaft seal. Typically, par-

affinic or naphthenic mineral oils are used, though synthetics are

being used more frequently on some applications.

The oil fulfills three primary purposes: sealing, cooling, and

lubrication. The oil tends to fill any leakage paths between and

around the screws. This provides a good volumetric efficiency even

at high compression ratios. Normal volumetric efficiency exceeds

85% even with a compression ratio of 25. The oil sealing also helps

maintain good volumetric efficiency with decreased operating

speeds. The cooling function of the oil transfers much of the heat of

compression from the gas to the oil, keeping typical discharge tem-

peratures below 90°C. This allows high compression ratios without

the danger of oil breakdown. The oil’s lubrication function protects

the bearings, seals, and screw contact areas.

Oil injection to the screw compressor is normally achieved by

one of two methods:

• An oil pump operates and builds pressure over compressor dis-

charge pressure for oil injection. The pump may be required when

the screw compressor is operating at a low compression ratio or if

the compressor bearing design requires oil pressure greater than

compressor discharge pressure.

• Operation without a pump relies on the differential pressure across

the screw compressor as the driving force for the oil injection.

Some screw compressors may use a combination of both meth-

ods to achieve proper oil injection. The pump may only operate for

a period of time when the compression ratio is below a set value.

This option is shown schematically in Figure 5.

Oil injection requires an oil separator to remove the oil from the

high-pressure refrigerant. Oil separators are designed to satisfy re-

quirements of system type, refrigerant, and heat transfer equip-

ment being used. Modern separation equipment routinely limits

Fig. 4 Rotary Vane Booster Compressor Cooling

with Lubricant

Fig. 5 Screw Compressor Flow Diagram with

Optional Oil Pump](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-50-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

Carbon Dioxide Refrigeration Systems 3.3

by measuring saturated suction pressure and gas cooler outlet tem-

perature and regulating the refrigerant flow to maintain an optimum

discharge pressure. Achieving as low a temperature at the gas cooler

outlet as possible is key to good efficiency, suggesting that there is a

need for evaporatively cooled gas coolers, although none are cur-

rently on the market. Other devices, such as expanders, have been

developed to achieve the same effect by reducing the enthalpy during

the expansion process and using the recovered work in the compres-

sor to augment the electrical input.

CO2 Cascade System

The cascade system consists of two independent refrigeration

systems that share a common cascade heat exchanger. The CO2 low-

temperature refrigerant condenser serves as the high-temperature

refrigerant evaporator; this thermally connects the two refrigeration

circuits. System size influences the design of the cascade heat

exchanger: large industrial refrigeration system may use a shell-

and-tube vessel, plate-and-frame heat exchanger, or plate-and-shell

type, whereas commercial systems are more likely to use brazed-

plate, coaxial, and tube-in-tube cascade heat exchangers. In chilling

systems, the liquid CO2 is pumped from the receiver vessel below

the cascade heat exchanger to the heat load. In low-temperature

applications, the high-pressure CO2 liquid is expanded to a lower

pressure and a compressor is used to bring the suction gas back up

to the condensing pressure.

Using a cascade system allows a reduced high-temperature

refrigerant charge. This can be important in industrial applications

to minimize the amount of ammonia on site, or in commercial sys-

tems to reduce HFC refrigerant losses.

CO2 cascade systems are configured for pumped liquid recircu-

lation, direct expansion, volatile secondary and combinations of

these that incorporate multiple liquid supply systems.

Low-temperature cascade refrigeration application include cold

storage facilities, plate freezers, ice machines, spiral and belt freez-

ers, blast freezers, freeze drying, supermarkets, and many other

food and industrial product freezing systems.

Some theoretical studies [e.g., Vermeeren et al. (2006)] have sug-

gested that cascade systems are inherently less efficient than two-

stage ammonia plants, but other system operators claim lower

energy bills for their new CO2 systems compared to traditional

ammonia plants. The theoretical studies are plausible because intro-

ducing an additional stage of heat transfer is bound to lower the

high-stage compressor suction. However, additional factors such as

the size of parasitic loads (e.g., oil pumps, hot gas leakage) on the

low-stage compressors, the effect of suction line losses, and the

adverse effect of oil in low-temperature ammonia plants all tend to

offset the theoretical advantage of two-stage ammonia system, and

in the aggregate the difference in energy consumption one way or

the other is likely to be small. Other factors, such as reduced ammo-

nia charge, simplified regulatory requirements, or reduced operator

staff, are likely to be at least as significant in the decision whether to

adopt CO2 cascades for industrial systems.

In commercial installations, the greatest benefit of a CO2 cascade

is the reduction in HFC inventory, and consequent probable reduc-

tion in HFC emission. Use of a cascade also enables the operator to

retain existing HFC compressor and condenser equipment when

refurbishing a facility by connecting it to a CO2 pump set and

replacing the evaporators and low-side piping. End users in Europe

and the United States suggest that CO2 cascade systems are simpler

and easier to maintain, with fewer controls requiring adjustment,

than the HFC systems that they are replacing. This indicates that

they are inherently more reliable and probably cheaper to maintain

than conventional systems. If the efficiency is equivalent, then the

cost of ownership will ultimately be cheaper. However, it is not clear

if these benefits derive from the higher level of engineering input

required to introduce the new technology, or whether they can be

maintained in the long term.

2. SYSTEM DESIGN

Transcritical CO2 Systems

Recent advances in system component design have made it pos-

sible to operate in previously unattainable pressure ranges. The

development of hermetic and semihermetic multistage CO2 com-

pressors provided the economical ability to design air-cooled tran-

scritical systems that are efficient, reliable, and cost effective. Today,

transcritical systems are commercially available in sizes from the

smallest appliances to entire supermarket systems. Figures 3 and 4

shows examples of simple transcritical systems. Heat rejection to

atmosphere is by cooling the supercritical CO2 gas without phase

change. For maximum efficiency, the gas cooler must be able to

operate as a condenser in colder weather, and the control system must

be able to switch from gas cooler operation (where outflow from the

air-cooled heat exchanger is restricted) to condenser operation

Fig. 3 Transcritical CO2 Refrigeration Cycle in Appliances

and Vending Machines

Fig. 4 CO2 Heat Pump for Ambient Heat to Hot Water](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-77-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

Carbon Dioxide Refrigeration Systems 3.7

maximum solubility limit in a CO2 system, problems may occur,

especially if the temperature is below 0°C. In this case, the water

freezes, and ice crystals may block control valves, solenoid valves,

filters, and other equipment.

If the water concentration in a CO2 system exceeds the saturation

limit, it creates carbonic acid, which can cause equipment failures

and possibly internal pipe corrosion. Filter-driers should be located

at all main liquid feed locations.

Because the entire CO2 system is at positive pressure during all

operating conditions, the most likely time for moisture penetration

is during charging. The appropriate specification for water content

depends on the size of the system and its intended operating tem-

perature. Chilling systems are more tolerant of water than freezers,

and industrial systems with large liquid receivers are likely to be

more tolerant than small direct-expansion (DX) circuits. It is imper-

ative that the CO2 is specified with a suitable water content. Refrig-

erant grade, with a content less than 5 ppm, is suitable for small

commercial systems; larger plant may use cryogenic grade, with a

content less than 20 ppm. The content should be certified by the ven-

dor and tested on site before installing in the system. On small sys-

tems, it may also be appropriate to charge through a filter-drier.

3. SYSTEM SAFETY

Safety is an important factor in the design of every refrigeration

system, and is one of the main reasons why carbon dioxide is

gaining acceptance as a refrigerant of the future. CO2 is a natural

refrigerant and considered environmentally safe. As a refrigerant, it

is not without potential risks, but they are substantially smaller than

those of other refrigerants. It is a slightly toxic, odorless, colorless

gas with a slightly pungent, acid taste. Carbon dioxide is a small but

important constituent of air. CO2 will not burn or support combus-

tion. An atmosphere containing of more than 10% CO2 will extin-

guish an open flame.

Mechanical failure in refrigeration equipment and piping can

course a rapid increase in concentration levels of CO2. When in-

haled at elevated concentrations, carbon dioxide may produce mild

narcotic effects, stimulation of the respiratory centre, and asphyxi-

ation, depending on concentration present.

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Admin-

istration (OSHA) limits the permissible exposure limit (PEL) time

weighted average (TWA) concentration that must not be exceed

during any 8 h per day, 40 h per week, to 5000 ppm. The OSHA

short-term exposure limit (STEL), a 15 min TWA exposure that

should not be exceeded, is 30 000 ppm. In other countries (e.g., the

United Kingdom), the STEL is lower, at 15 000 ppm.

At atmospheric pressure, carbon dioxide is a solid, which sub-

limes to vapor at –56.6°C. All parts of a charged CO2 refrigerating

system are above atmospheric pressure. Do not attempt to break

piping joints or to remove valves or components without first ensur-

ing that the relevant parts of the system have been relieved of pres-

sure.

When reducing pressure or transferring liquid carbon dioxide,

care is necessary to guard against blockages caused by solid carbon

dioxide, which forms at pressures below 517 kPa. If a blockage

occurs, it must be treated with caution. No attempt should be made

to accelerate the release of pressure by heating the blocked compo-

nent.

In a room where people are present and the CO2 concentration

could exceed the refrigerant concentration limit of 0.9 kg/10 m3 in

the event of a leak, proper detection and ventilation are required.

When detectors sense a dangerous level of CO2 in a room, the alarm

system must be designed to make sure all people in the room are

evacuated and no one is allowed to reenter until concentration levels

return to acceptable ranges. Protective clothing, including gloves

and eyewear, should be standard in locations that contain CO2

equipment or controls, or where service work is done.

4. PIPING

Carbon Dioxide Piping Materials

When selecting piping material for CO2 refrigeration systems,

the operating pressure and temperature requirements must be under-

stood. Suitable piping materials may include copper, carbon steel,

stainless steel, and aluminum.

Many transcritical systems standardize on brazed air-conditioning

and refrigeration (ACR) copper piping for the low-pressure side of

the system, because of its availability. For pressures above 4.1 MPa,

the annealing effect of brazing can weaken copper pipe, so pipework

should be welded steel. Alternatively, cold-formed mechanical per-

manent joints can be used with copper pipe if the pipe and fittings

are suitably pressure rated. Small-diameter copper tubing meets the

requirement pressure ratings. The allowable internal pressure for

copper tubing in service is based on a formula used in ASME Stan-

dard B31 and ASTM Standard B280:

p = (2)

where

p = allowable pressure

S = allowable stress [i.e., allowable design strength for continuous

long-term service, from ASME (2007)]

tm = wall thickness

D = outside diameter

Carbon Steel Piping for CO2

Low-temperature seamless carbon steel pipe (ASTM Standard

A333) Grade 6 is suited for conditions within refrigeration systems.

Alternatively a number of common stainless steel alloys provide

adequate low temperature properties.

Stainless steel, aluminum, and carbon steel piping require qual-

ified welders for the piping installation.

Pipe Sizing

For the same pressure drop, CO2 has a corresponding tempera-

ture penalty 5 to 10 times smaller than ammonia and R-134a have

(Figure 11). For a large system with an inherently large pressure

drop, the temperature penalty with CO2 is substantially less than the

same pressure drop using another refrigerant.

Because of CO2’s physical properties (particularly density), the

vapor side of the system is much smaller than in a typical ammonia

system, but the liquid side is similar or even larger because CO2’s

Fig. 10 Water Solubility in CO2

(Adapted from Vestergaard 2007)

2Stm

D – 0.08tm

-----------------------------

-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-81-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

6.8 2018 ASHRAE Handbook—Refrigeration (SI)

Copper Plating

Copper plating is the formation of a copper film on steel surfaces

in refrigeration and air-conditioning compressors. A blush of copper

is often discernible on compressor bearing and valve surfaces when

machines are cut apart. After several hours of exposure to air, this

thin film becomes invisible, probably because metallic copper is

converted to copper oxide. In severe cases, the copper deposit

can build up to substantial thickness and interfere with com-

pressor operation. Extreme copper plating can cause compressor

failure.

Although the exact mechanism of copper plating is not com-

pletely understood, early work by Spauschus (1963), Steinle and

Bosch (1955), and Steinle and Seemann (1951, 1953) demonstrated

that three distinct steps must occur: (1) copper oxidation, (2) solu-

bilization and transport of copper ions, and (3) deposition of copper

onto iron or steel.

In step 1, copper oxidizes from the metallic (0 valent) state to

either the +1 or +2 oxidation state. Under normal operating condi-

tions, this chemical process does not occur with a lubricant, and is

unlikely to occur with carboxylic acids. The most likely source of

oxidizing agents is system contaminants, such as air (oxygen), chlo-

rine-containing species (CFC refrigerants or cleaning solvents, sol-

der fluxes), or strong acids.

Step 2 is dissolution of the copper ions. Spauschus postulated

that an organic complex of the copper and olefins is the soluble spe-

cies in mineral oils. Oxygen-containing lubricants are much more

likely to solubilize metal ions and/or complexes via coordination

with the oxygen atoms. Once soluble, the copper can move through-

out the refrigeration system.

Step 3 is deposition of the copper onto iron surfaces, an electro-

chemical process in which electrons transfer from iron to copper,

resulting in copper metal (0 valent) plating on the surface of the

iron and the concomitant generation of iron ions. This is most

likely to occur on hot, clean iron surfaces and is often seen on bear-

ing surfaces.

Thomas and Pham (1989) compared copper plating in R-12/

mineral oil and R-134a/PAG systems. They showed that R-134a/

PAG systems produce much less total copper (in solution and as

precipitate) than R-12/mineral oil systems, and that water did not

significantly affect the amount of copper produced. In an R-134a/

PAG system, copper is largely precipitated. In an R-12/mineral oil

system, copper is found in solution when dry and precipitates

when wet. Walker et al. (1960) found that water below the satura-

tion level has no significant effect on copper plating for R-12/

mineral oil systems. Spauschus (1963) observed that copper plat-

ing in sealed glass tubes is more prevalent with medium-refined

naphthenic pale oil than with highly refined white oil, and con-

cluded that the refrigerant/lubricant reaction is an essential pre-

cursor for gross copper plating. The excess acid produced by

refrigerant decomposition has little effect on copper solubility, but

facilitates plating. Herbe and Lundqvist (1996, 1997) examined a

large number of systems retrofitted from R-12 to R-134a for con-

taminants and copper plating. They reported that copper plating

does not occur in retrofitted systems where the level of contami-

nants is low.

ASHRAE research project RP-1249 examined the steps of cop-

per plating in refrigeration and air-conditioning systems (Kauffman

2005). The study used glass vial tests to simulate acidic oil drops

adhering to copper tubing and/or compressor steel surfaces with and

without air contamination, and analyzed copper plating removed

from field refrigeration systems. The findings were as follows:

• Copper plating is most likely an electrochemical process involv-

ing copper carboxylates.

• The steel surface must be corroded for copper plating to occur.

• Water promotes plating by encouraging steel surface corrosion

and providing a conductive path.

• Air only has an effect when copper metal surfaces are corroded.

• Passivation of steel surfaces does not inhibit copper plating.

• Copper platings created in the lab and field are similar in mor-

phology and composition.

• Copper plating occurs in stationary and nonwearing rotating steel

surfaces.

Corrosion

Corrosion of Refrigerant Piping and Heat Exchangers. Cor-

rosion on copper tubing used for refrigerant piping and heat

exchangers can cause leaks that release refrigerant to the atmo-

sphere, shorten equipment life, and result in property damage

because of failed temperature control. Corrosive mechanisms are

(1) stress corrosion cracking caused by ammonia and related com-

pounds from refrigerant-tube insulation material, (2) formicary cor-

rosion caused by acetic and formic acids (e.g., from interior house

paint, oak, engineered wood products, carpet, and adhesives), and

(3) sulfur corrosion caused by drywall out-gassing, biofeed synthe-

sis, organic fertilizers, and sewer gases.

Formicary Corrosion. Formicary (“ants’ nest”) corrosion com-

monly appears in copper tubing in air-conditioning and refrigera-

tion equipment, and also has been reported in heat pumps. Damage

typically is found in shielded areas (crevices) in closed heat

exchanger bundles or between copper tubing and aluminum fins.

Formicary corrosion occurs when air, moisture, and certain low-

molecular-mass organic compounds are present. Degradation prod-

ucts are carboxylic acids such as formic and acetic acids.

Control measures include removing any one of the causes,

selecting substances with low carboxylic content, and using more

corrosion-resistant alloys and hydrophobic coatings that reduce the

effect of humidity (Corbett and Severance 2005).

Even though formicary corrosion occurs outside the refrigeration

system, the problem can eventually affect the internal system

because of system conditions or migration of contaminants into the

system.

Effects of Unsaturated Contaminants on HFC or HFO

Refrigerants and Lubricants

In HVAC&R systems, unsaturated fluorocarbon contaminants in

refrigerants may result in reaction products that could cause prob-

lems in system performance or reliability. However, the 40 mg/kg

limit for unsaturated halogenated contaminants in new and

reclaimed refrigerants set by AHRI Standard 700 has proven to be

more restrictive than expected for reclaimers, recyclers, and

HVAC&R system providers. In addition, it may not be appropriate

to classify all unsaturated compounds as unstable and blanket them

under the same restrictive limit: compounds such as hydrofluoroole-

fins (HFOs) have been tested as low-global-warming-potential

(GWP) alternative refrigerants and shown to have acceptable stabil-

ity in some applications. Rohatgi (2016) examined the effects of

halogenated unsaturated contaminants in refrigerants on the stabil-

ity of refrigerant/lubricant systems, and recommended a concentra-

tion limit specific to the unsaturated contaminant, below which the

refrigerant/lubricant system is thermally stable. Based on criteria

such as visual changes, total acid numbers (TAN), organic anion

concentration, and dissolved metal concentrations after aging,

Rohatgi concluded that the R134a/POE system was as stable as the

control (without contaminant) when the concentration of its con-

taminants [R-1130, R-1130(E), R-1131, and R-1234yf] was less

than 1000 mg/kg. The R-1234yf/POE system was stable when its

contaminants [R-1225ye(Z), R-1233xf, and R-1243zf] were less

than 5000 mg/kg, whereas the R-123/mineral oil system was stable

when its contaminants (R-1122, R-1123, and R-1131) were less than

30 000 mg/kg. These maximum concentration limits were however](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-108-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

Control of Moisture and Other Contaminants in Refrigerant Systems 7.7

• Plugging expansion valve screens, expansion valve ports, or cap-

illary tubing

• Depositing on suction or discharge valve seats, significantly re-

ducing compressor efficiency

• Plugging oil holes in compressor parts, leading to improper lubri-

cation

• Increasing the rate of chemical breakdown [e.g., at elevated tem-

peratures, R-22 decomposes more readily when in contact with

iron powder, iron oxide, or copper oxide (Norton 1957)]

• Plugging driers, filters, and filter-driers

Liquid-line filter-driers, suction filters, and strainers isolate con-

taminants from the compressor and expansion valve. Filters mini-

mize return of particulate matter to the compressor and expansion

valve, but the capacity of permanently installed liquid and/or suction

filters must accommodate this particulate matter without causing

excessive, energy-consuming pressure losses. Equipment manufac-

turers should consider the following procedures to ensure proper

operation during the design life:

1. Develop cleanliness specifications that include a reasonable

value for maximum residual matter. Some manufacturers specify

allowable quantities in terms of internal surface area. ASTM

Standard B280 allows a maximum of 37 mg of contaminants per

square metre of internal surface.

2. Multiply the factory contaminant level by a suitable safety factor

to allow for solid contaminants added during installation. This

factor depends on the type of system and the previous experience

of the installers, among other considerations.

3. Determine maximum pressure drop to be incurred by the suction

or liquid filter when loaded with the quantity of solid matter cal-

culated in Step 2.

4. Conduct filtration capability tests per ASHRAE Standard 63.2.

5. Select driers for each system per its capacity requirements and

test data. In addition to contaminant removal capacity, tests can

evaluate filter efficiency, maximum escaped particle size, and

average escaped particle size.

Very small particles passing through filters tend to accumulate in

the crankcase. Most compressors tolerate a small quantity of these

particles without allowing them into the oil pump inlet, where they

can damage running surfaces.

Organic Contaminants: Sludge, Wax, and Tars

Organic contaminants in a refrigerating system with a mineral oil

lubricant can appear when organic materials such as oil, insulation,

varnish, gaskets, and adhesives decompose. As opposed to inorganic

contaminants, these materials are mostly carbon, hydrogen, and oxy-

gen. Organic materials may be partially soluble in the refrigerant/

lubricant mixture or may become so when heated. They then circu-

late in the refrigerating system and can plug small orifices. Organic

contaminants in a refrigerating system using a synthetic polyol ester

lubricant may also generate sludge. The following contaminants

have demonstrated the ability to compromise system chemistry and

should be avoided:

• Paraffin (typically found in mineral oil lubricants)

• Silicone (found in some machine lubricants)

• Phthalate (found in some machine lubricants)

Whether mineral oil or synthetic lubricants are used, some

organic contaminants remain in a new refrigerating system during

manufacture or assembly. For example, excessive brazing paste

introduces a waxlike contaminant into the refrigerant stream. Cer-

tain cutting lubricants, corrosion inhibitors, or drawing compounds

frequently contain paraffin-based compounds. These lubricants can

leave a layer of paraffin on a component that may be removed by the

refrigerant/lubricant combination and generate insoluble material in

the refrigerant stream. Organic contamination also results during

the normal method of fabricating return bends. The die used during

forming is lubricated with these organic materials, and afterwards

the return bend is brazed to the tubes to form the evaporator and/or

condenser. During brazing, residual lubricant inside the tubing and

bends can be baked to a resinous deposit.

If organic materials are handled improperly, certain contami-

nants remain. Resins used in varnishes, wire coating, or casting seal-

ers may not be cured properly and can dissolve in the refrigerant/

lubricant mixture. Solvents used in washing stators may be ad-

sorbed by the wire film and later, during compressor operation,

carry chemically reactive organic extractables. Chips of varnish, in-

sulation, or fibers can detach and circulate in the system. Portions of

improperly selected or cured rubber parts or gaskets can dissolve in

the refrigerant.

Refrigeration-grade mineral oil decomposes under adverse

conditions to form a resinous liquid or a solid frequently found on

refrigeration filter-driers. These mineral oils decompose notice-

ably when exposed for as little as 2 h to temperatures as low as

120°C in an atmosphere of air or oxygen. The compressor manu-

facturer should perform all high-temperature dehydrating opera-

tions on the machines before adding the lubricant charge. In

addition, equipment manufacturers should not expose compres-

sors to processes requiring high temperatures unless the compres-

sors contain refrigerant or inert gas.

The result of organic contamination is frequently noticed at the

expansion device. Materials dissolved in the refrigerant/lubricant

mixture, under liquid line conditions, may precipitate at the lower

temperature in the expansion device, resulting in restricted or

plugged capillary tubes or sticky expansion valves. A few milli-

grams of these contaminants can render a system inoperative.

These materials have physical properties that range from a fluffy

powder to a solid resin entraining inorganic debris. If the contam-

inant is dissolved in the refrigerant/lubricant mixture in the liquid

line, it will not be removed by a filter-drier.

Chemical identification of these organic contaminants is very dif-

ficult. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), gas chroma-

tography with mass spectroscopy (GCMS), liquid chromatography

with mass spectroscopy (LCMS), and other mass spectroscopy-

coupled analytical instruments can characterize the type of organic

groups and compounds present in contaminants. Materials found in

actual systems vary from waxlike aliphatic hydrocarbons to resinlike

materials containing double bonds, carbonyl groups, and carboxyl

groups. In some cases, organic compounds of copper and/or iron

have been identified.

These contaminants can be eliminated by carefully selecting

materials and strictly controlling cleanliness during manufacture

and assembly of the components as well as the final system.

Because heat degrades most organic materials and enhances chem-

ical reactions, avoid operating conditions with excessively high dis-

charge or bearing surface temperatures to prevent formation of

degradation products.

Residual Cleaning Agents

Mineral Oil Systems. Solvents used to clean compressor parts

are likely contaminants if left in refrigerating equipment. These

solvents are considered pure liquids without additives. If additives

are present, they are reactive materials and should not be in a re-

frigerating system. Some solvents are relatively harmless to the

chemical stability of the refrigerating system, whereas others initi-

ate or accelerate degradation reactions. For example, the common

mineral spirits solvents are considered harmless. Other common

compounds react rapidly with hydrocarbon lubricants (Elsey et al.

1952).

Polyol Ester Lubricated Systems. Typical solvents used in

cleaning mineral oil systems are not compatible with polyol ester](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-123-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

7.10 2018 ASHRAE Handbook—Refrigeration (SI)

Contaminant control concerns for retrofitting a system to an al-

ternative refrigerant fall into the following categories:

• Cross-contamination of old and new refrigerants. This

should be avoided even though there are usually no chemical

compatibility problems between the original refrigerants and

their replacements. One problem with mixing refrigerants is that

it is difficult to determine system performance after retrofit.

Pressure/temperature relationships are different for a blend of

two refrigerants than for each refrigerant individually. A second

concern is that if the new refrigerant charge must be removed in

the future, the mixture may not be reclaimable (DuPont 1992).

The phaseout of HCFCs has coincided with a significant

increase in cross-contaminated refrigerants, especially R-22.

• Cross-contamination of old and new lubricant. Refrigerant

manufacturers claim some replacement refrigerants are direct

drop-ins, with no specific requirement for change in lubricant.

Depending on the particular refrigerant and type of system,

equipment manufacturers generally specify a recommended

replacement lubricant. In some cases, the new lubricant is

incompatible with the old one or with chlorinated residues pres-

ent. In other cases, the old lubricant is insoluble with the new

refrigerant and tends to collect in the evaporator, interfering

with heat transfer. For example, when mineral oil is replaced by

a polyol ester lubricant during retrofit to an HFC refrigerant, a

typical recommendation is to reduce the old oil content to 5% or

less of the nominal oil charge (Castrol 1992). Some retrofit rec-

ommendations specify lower levels of acceptable contamination

for polyol ester lubricant/HFC retrofits, so original equipment

manufacturers recommendations should be obtained before

attempting a conversion. On larger centrifugal systems, per-

forming a system cleanup to reduce oil concentration before ret-

rofit can prevent the need for several costly oil changes after the

retrofit, and can significantly diminish the need for later system

decontamination to address sludge build-up. Even when the

level of the original lubricant is significantly reduced, if the

replacement lubricant [e.g., POE (polar)] has a different polarity

than the original [e.g., mineral oil (nonpolar)], the solubility of

built-up residues in the system may change. This change in sol-

ubility may liberate sludge particles, which can cause blockages

in narrower parts of the system, such as control orifices and cap-

illary tubes, reducing system capacity or functionality. Larger

particulates can also cause premature compressor failure.

• Chemical compatibility of old system components with new

fluids. One of the preparatory steps in a retrofit is to confirm that

either the existing materials in the system are acceptable or that

replacement materials are on hand to be installed in the system

during the retrofit. Fluorocarbon refrigerants generally have sol-

vent properties, and some are very aggressive. This characteris-

tic can lead to swelling and extrusion of polymer O rings,

undermining their sealing capabilities. Material can also be

extracted from polymers, varnishes, and resins used in hermetic

motor windings. These extracts can then collect in expansion

devices, interfering with system operation. Residual manufac-

turing fluids such as those used to draw wire for compressor

motors can be extracted from components and deposited in

areas where they can interfere with operation. Suitable materials

of construction have been identified by equipment manufactur-

ers for use with HFC refrigerant systems.

Drier media must also be chemically compatible with the new re-

frigerant and effective in removing moisture, acid, and particulates

in the presence of the new refrigerant. Drier media commonly used

with CFC refrigerants tend to accept small HFC refrigerant mole-

cules and lose moisture retention capability (Cohen and Blackwell

1995), although some media have been developed that minimize

this tendency. Compatibility with next-generation, low-global-

warming-potential (LGWP), and natural refrigerants requires vali-

dation, as well.

5. CHILLER DECONTAMINATION

Chiller decontamination is used to clean reciprocating, rotary

screw, and centrifugal machines. Large volumes of refrigerant are

circulated through a contaminated chiller while continuously

being reclaimed. It has been used successfully to restore many

chillers to operating specifications. Some chillers have been saved

from early retirement by decontamination procedures. Variations

of the procedure are myriad and have been used for burnouts,

water-flooded barrels, particulate incursions, chemical contamina-

tion, brine leaks, and oil strips. One frequently used technique is

to perform numerous batch cycles, thus increasing the velocity-

based cleansing component. Excess oil is stripped out to improve

chiller heat transfer efficiency. The full oil charge can be removed

in preparation for refrigerant conversion.

Low-pressureunits require differentmachinery than high-pressure

units. It is best to integrate decontamination and mechanical

services early into one overall procedure. On machines that require

compressor rebuild, it is best to perform decontamination work

while the compressor is removed or before it is rebuilt, particularly

for reciprocating units. Larger-diameter or relocated access ports

may be requested. The oil sump will be drained. For chillers that

cannot be shut down, special online techniques have been developed

using reclamation. The overall plan is coordinated with operations

personnel to prevent service interruptions. For some decontamina-

tion projects, it is advantageous to have the water boxes open; in

other cases, closed. Intercoolers offer special challenges.

6. SYSTEM SAMPLING

Analysis of refrigerant and lubricant, either as follow-up to a

retrofit, for troubleshooting a refrigeration or chiller system, or as

part of a routine maintenance plan, helps validate system perfor-

mance and identify potential system problems before they become

serious issues. Refrigerant analysis can identify specific system

contaminants such as moisture, noncondensable gases, acids,

chlorides, particulate, high-boiling-point residue (e.g., lubricant),

and other refrigerants. Under AHRI Standard 700 procedures, the

analysis measures specific levels of each contaminant except for

chlorides and particulates, which are evaluated on a pass/fail

basis.

Lubricant analysis similarly measures several trace elements,

including additives formulated for the particular lubricant. Standard

lubricant analysis also measures viscosity, moisture, and total acid

number. For lubricants with suspended debris, consider ferro-

graphic analysis or inductively coupled plasma (ICP) testing for ele-

mental analysis or a particle count and size distribution. Debris can

also be filtered out and visually assessed by microscopy or compo-

sitionally analyzed by scanning electron microscope with electron

dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) and x-ray fluorescence (XRF)

for elements identification, x-ray diffraction (XRD) for compounds

identification, or other methods.

For chillers, water chemistry is also very important to maintain-

ing an efficient and reliable system. (Water treatment is addressed in

Chapter 49 of the 2015 ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Applications.)

Note that contaminants usually infiltrate the system or are generated

very slowly. As a result, the system can become inefficient and dete-

riorate to the point of failure without noticeable warning. Regular,

periodic sampling and trending the results promotes more efficient

and reliable system operation, which can significantly reduce both

operating and maintenance costs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-126-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

8.1

CHAPTER 8

EQUIPMENT AND SYSTEM DEHYDRATING,

CHARGING, AND TESTING

Dehydration (Moisture Removal) ................................................................................................... 8.1

Moisture Measurement.................................................................................................................... 8.3

Charging ......................................................................................................................................... 8.4

Testing for Leaks............................................................................................................................. 8.4

Performance Testing ....................................................................................................................... 8.5

ROPER dehydration, charging, and testing of packaged refrig-

Peration systems and components (compressors, evaporators,

and condensing coils) help ensure proper performance and extend

the life of refrigeration systems. This chapter covers the methods

used to perform these functions. It does not address criteria such as

allowable moisture content, refrigerant quantity, and performance,

which are specific to each machine.

1. DEHYDRATION (MOISTURE REMOVAL)

Factory dehydration may be feasible only for certain sizes of

equipment. On large equipment, which is open to the atmosphere

when connected in the field, factory treatment is usually limited to

purge and backfill, with an inert holding charge of nitrogen. In most

instances, this equipment is stored for short periods only, so this

method suffices until total system evacuation and charging can be

done at the time of installation.

Excess moisture in refrigeration systems may lead to freeze-up of

the capillary tube or expansion valve. It also has a negative effect on

thermal stability of certain refrigeration oils [e.g., polyol ester

(POE)]. (Chapter 7 has more information on moisture and other con-

taminants in refrigerant systems.)

Except for freeze-up, these effects are not normally detected by a

standard factory test.

It is important to use a dehydration technique that yields a safe

moisture level without adding foreign elements or solvents, because

contaminants can cause valve breakage, motor burnout, and bearing

and seal failure. In conjunction with dehydration, an accurate

method of moisture measurement must be established. Many fac-

tors, such as the size of the unit, its application, and type of refriger-

ant, determine acceptable moisture content. Table 1 shows moisture

limits recommended by various manufacturers for particular refrig-

eration system components.

Sources of Moisture

Moisture in refrigerant systems can be (1) retained on the sur-

faces of metals; (2) produced by combustion of a gas flame; (3) con-

tained in liquid fluxes, oil, and refrigerant; (4) absorbed in the

hermetic motor insulating materials; (5) derived from the factory

ambient at the point of unit assembly; and (6) provided by free water.

Moisture contained in the refrigerant has no effect on dehydration of

the component or unit at the factory. However, because the refriger-

ant is added after dehydration, it must be considered in determining

the overall moisture content of the completed unit. Moisture in oil

may or may not be removed during dehydration, depending on when

the oil is added to the component or system.

Bulk mineral oils, as received, have 20 to 30 mg/kg of moisture.

Synthetic POE lubricants have 50 to 85 mg/kg; they are highly

hygroscopic, so they must be handled appropriately to prevent

moisture contamination. Refrigerants have an accepted commer-

cial tolerance of 10 to 15 mg/kg on bulk shipments. Controls at the

factory are needed to ensure these moisture levels in the oils and

refrigerant are maintained.

Newer insulating materials in hermetic motors retain much less

moisture compared to the old rag paper and cotton-insulated motors.

However, tests by several manufacturers have shown that the stator

is still the major source of moisture in compressors.

Dehydration by Heat, Vacuum, or Dry Air

Heat may be applied by placing components in an oven or by

using infrared heaters. The oven temperature should be selected

carefully to prevent damage to the synthetics used and to avoid

breakdown of any residual run-in oil that may be present in compres-

sors. Oven temperatures of 80 to 170°C are usually maintained. Air

in the oven must be maintained at low humidity. When dehydrating

by heat alone, the time and escape area are critical; therefore, the size

of parts that can be economically dehydrated by this method is

restricted.

The vacuum method reduces the boiling point of water below the

ambient temperature. The moisture then changes to vapor, which is

pumped out by the vacuum pump. Table 3 in Chapter 1 of the 2017

ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals shows the relationship of tem-

perature and pressure for water at saturation.

Vacuum is classified according to the following absolute pressure

ranges:

Low Vacuum 101.325 to 3.5 kPa

Medium Vacuum 3500 to 0.130 Pa

High Vacuum 130 to 0.13 mPa

Very High Vacuum 130 to 0.13 Pa

Ultrahigh Vacuum 0.13 Pa and below

The degree of vacuum achieved and the time required to obtain

the specified moisture level are a function of the (1) type and size of

vacuum pump used, (2) internal volume of the component or system,

(3) size and composition of water-holding materials in the system,

(4) initial amount of moisture in the volume, (5) piping and fitting

sizes, (6) shape of the gas passages, and (7) external temperatures

maintained. The pumping rate of the vacuum pump is critical only if

the unit is not evacuated through a conductance-limiting orifice such

as a purge valve. Excessive moisture content, such as a pocket of

puddled water, takes a long time to remove because of the volume

expansion to vapor.

Vacuum measurements should be taken directly at the equipment

(or as close to it as possible) rather than at the vacuum pump. Small

tubing diameters or long tubing runs between the pump and the

equipment should be avoided because line/orifice pressure drops

reduce the actual evacuation level at the equipment.

The preparation of this chapter is assigned to TC 8.1, Positive Displacement

Compressors.

Related Commercial Resources](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-129-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

Equipment and System Dehydrating, Charging, and Testing 8.5

method is normally used to measure the total leakage rate from all

joints simultaneously. The main limitation for this method is that the

costs for test equipment and consumables are higher than for other

leak detection methods. Test levels for production equipment are

typically set near 10–2 mm3/s.

The required concentration of helium depends on the maximum

leak permissible, the configuration of the system under test, the time

the system can be left in the helium atmosphere, and the vacuum

level in the system; the lower the vacuum level, the higher the

helium readings. The longer a unit is exposed to the helium atmo-

sphere, the lower the concentration necessary to maintain the

required sensitivity. If, because of the shape of the test unit, a leak is

distant from the point of sampling, a good vacuum must be drawn,

and sufficient time must be allowed for traces of helium to appear on

the mass spectrometer.

As with other methods described in this chapter, the best testing

procedure when using the spectrometer is to locate and characterize

calibrated leaks at extreme points of the test unit and then to adjust

exposure time and helium concentration to allow cost-effective test-

ing. One manufacturer reportedly found leaks of 1.4 g of refrigerant

per year by using a 10% concentration of helium and exposing the

tested system for 10 min.

The sensitivity of the mass spectrometer method can be limited

by the characteristics of the tested system. Because only the total

leakage rate is found, it is impossible to tell whether a leakage rate

of, for example, 30 g per year is caused by one fairly large leak or

several small leaks. If the desired sensitivity rejects units outside the

sensitivity range of tests listed earlier in this chapter, it is necessary

to use a helium probe to locate leaks. In this method, the compo-

nent or system to be probed is fully evacuated to clear it of helium;

then, while the system is connected to the mass spectrometer, a fine

jet of helium is sprayed over each joint or suspect area. With large

systems, a waiting period is necessary because some time is

required for the helium to pass from the leak point to the mass spec-

trometer. To save time, isolated areas (e.g., return bends on one end

of a coil) may be hooded and sprayed with helium to determine

whether the leak is in the region.

With a hand-held mass spectrometer, the unit to be tested is

pressurized with pure helium or a helium/nitrogen mixture, and

hand-held “sniffer” is used to check each joint and area of concern.

The required helium concentration and pressure depend on the max-

imum leak permissible. This method can be calibrated to detect

leaks of as low as 1.42 g of refrigerant per year, but it shares the

same disadvantages as electronic leak testing. Every joint and sus-

pect area should be explored.

Special Considerations

There are two general categories of leak detection: those that

allow a leak check before refrigerant is introduced into the system,

and those that require refrigerant. Methods that do not use refriger-

ant have the advantage that heat applied to repair a joint has no

harmful effects. On units containing refrigerant, the refrigerant must

be removed and the unit vented before any welding, brazing, or sol-

dering is attempted. This practice avoids refrigerant breakdown and

pressure build-up, which would prevent the successful completion

of a sound joint.

All leak-testing equipment must be calibrated frequently to

ensure maximum sensitivity. The electronic leak detector and the

mass spectrometer are usually calibrated with equipment furnished

by the manufacturer. Mass spectrometers are usually checked using

a flask containing helium. A glass orifice in the flask allows helium

to escape at a known rate; the operator calibrates the spectrometer

by comparing the measured escape rate with the standard.

The effectiveness of the detection system can best be checked

with calibrated leaks made of glass, which can be bought commer-

cially. These leaks can be built into a test unit and sent through the

normal leak detection cycles to evaluate the detection method’s

effectiveness. Ensure that the test leak site does not become closed;

the leakage rate of the test leak must be determined before and after

each system audit.

From a manufacturing standpoint, use of any leak detection

method should be secondary to leak prevention. Improper brazing

and welding techniques, unclean parts, untested sealing compounds

or improper fluxes and brazing materials, and poor-quality work re-

sult in leaks that occur in transit or later. Careful control and analysis

of each joint or leak point make it possible to concentrate tests on

areas where leaks are most likely to occur. If operators must scan

hundreds of joints on each unit, the probability of finding all leaks

is rather small, whereas concentration on a few suspect areas reduc-

es field failures considerably.

5. PERFORMANCE TESTING

Because there are many types and designs of refrigeration sys-

tems, this section only presents some specific information on com-

pressor testing and covers some important aspects of performance

testing of other components and complete systems.

Compressor Testing

The two prime considerations in compressor testing are power and

capacity. Secondary considerations are leakback rate, low-voltage

starting, noise, and vibration. The following are typical compressor

tests.

Testing Without Refrigerant. A number of tests measure com-

pressor power and capacity before the unit is exposed to refrigerant.

In cases where excessive power is caused by friction of running

gear, low-voltage tests spot defective units early in assembly. In

these tests, voltage is increased from a low or zero value to the value

that causes the compressor to break away, and this value is com-

pared with an established standard. When valves or valve plates are

accessible, the compressor can be tested by using an air pump for a

leakback. In this test, the air is put through the unit at fixed pressure

to determine the flow rate at which valves open. This flow rate is

then compared to an established standard. This method is effective

only when the valves are reasonably tight, and is difficult to use on

valves that must be run in before seating properly.

Take extreme care when using a compressor to pump air, because

the combination of oil, air, and high temperatures caused by com-

pression can result in a fire or explosion.

In a test using the compressor as an air pump, the discharge air-

flow is measured through a flowmeter, orifice, or other flow-measur-

ing device. Because air is compressed adiabatically in this test, the

discharge pressure must be low to prevent overheating of discharge

lines and oil oxidation if the test lasts longer than a few minutes. [The

discharge temperature of isentropic compression from ambient

condition is 140°C at 240 kPa (gage), but 280°C at 860 kPa (gage).]

When the compressor is run long enough to stabilize temperatures,

both power and flow can be compared with established limits. Dis-

charge temperature readings and speed measurements aid in analyz-

ing defective units. If a considerable amount of air is discharged or

trapped, the air used in the test must be dry enough to prevent con-

densation from causing rust or corrosion on the discharge side.

Another method of determining compressor performance re-

quires the compressor to pump from a free air inlet into a fixed vol-

ume. The time required to reach a given pressure is compared

against a maximum standard acceptable value. The pressure used in

this test is approximately 860 kPa (gage), so that a reasonable time

spread can be obtained. The time needed for measuring the com-

pressor’s capacity must be sufficient for accurate readings but short

enough to prevent overheating. Power readings can be recorded at

any time in the cycle. By shutting off the compressor, the leakback

rate can be measured as an additional check.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-133-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

9.6 2018 ASHRAE Handbook—Refrigeration (SI)

resale; this information is generally not available for recycled refrig-

erant.

Purity Standards

AHRI Standard 700 discusses halocarbon refrigerants, regard-

less of source, and defines acceptable levels of contaminants, which

are the same as the Federal Specifications for Fluorocarbon Refrig-

erants BB-F-1421B [superseded by A-A-58060, Fluorocarbon and

Other Refrigerants (2005)]. It specifies laboratory analysis methods

for each contaminant. Only fully equipped laboratories with trained

personnel are presently capable of performing the analysis.

Because AHRI Standard 700 is based on chemical analysis of a

sample from each batch after removal, it is not concerned with the

level of contaminants before removal (Manz 1995). This difference

from the “standard contaminated refrigerant sample” required in

AHRI Standard 740 is the basic distinction between analysis/recla-

mation and certification/recycling.

SAE Standards J1991 and J2099 list recycled refrigerant purity

levels for mobile air-conditioning systems using R-12 and R-134a,

respectively.

REFERENCES

ASHRAE members can access ASHRAE Journal articles and

ASHRAE research project final reports at technologyportal.ashrae

.org. Articles and reports are also available for purchase by nonmem-

bersintheonlineASHRAEBookstoreat www.ashrae.org/bookstore.

AHRI. 2017. Specifications for fluorocarbon refrigerants. Standard 700.

Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, Arlington, VA.

AHRI. 2016. Refrigerant recovery/recycling equipment. Standard 740. Air-

Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, Arlington, VA.

AHRI. 2015. Containers for recovered non-flammable fluorocarbon refrig-

erants. Guideline K. Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Insti-

tute, Arlington, VA.

AHRI. 2017. Assignment of refrigerant color containers. Guideline N. Air-

Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, Arlington, VA.

ASHRAE. 2013. Reducing the release of halogenated refrigerants from

refrigerating and air-conditioning equipment and systems. ANSI/

ASHRAE Standard 147-2013.

Clodic, D. 1997. Zero leaks. ASHRAE.

Clodic, D., and F. Sauer. 1994. The refrigerant recovery book. ASHRAE.

EPA.1996.Regulations governingsale of refrigerant. 61FR68505.U.S.Fed-

eral Register, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Kauffman, R.E. 1992. Chemical analysis and recycling of used refrigerant

from field systems. ASHRAE Transactions 98(1).

Manz, K.W. 1991. How to handle multiple refrigerants in recovery and recy-

cling equipment. ASHRAE Journal 33(4).

Manz, K.W. 1995. The challenge of recycling refrigerants. Business News

Publishing, Troy, MI.

Manz, K.W. 1996. Recycling alternate refrigerants R-404A, R-410A, and

R-507. Proceedings of the International Conference on Ozone Protec-

tion Technologies, Frederick, MD, pp. 411-419.

O’Meara, D.R. 1988. Operating experiences of a refrigerant recovery ser-

vices company. ASHRAE Transactions 94(2).

Parker, R.W. 1988. Reclaiming refrigerant in OEM plants. ASHRAE Trans-

actions 94(2).

RSES. 1991. Refrigerant service for the 90’s, 1st ed. Refrigeration Service

Engineers Society, Des Plaines, IL.

SAE. 2011. Standard of purity for use in mobile air-conditioning systems.

Standard J1991. Society of Automotive Engineers, Warrendale, PA.

SAE. 2012. Standard of purity for recycled R-134a (HFC-134a) and R-

1234yf (HFO-1234yf) for use in mobile air-conditioning systems. Stan-

dard J2099. Society of Automotive Engineers, Warrendale, PA.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ASNT. 2017. Nondestructive testing handbook, vol. 2: Leak testing, 4th ed.

American Society for Nondestructive Testing, Columbus, OH.

Kauffman, R.E. 1993. Sealed-tube tests of refrigerants from field systems

before and after recycling. ASHRAE Transactions 99(2):414-424.

Manz, K.W. 1988. Recovery of CFC refrigerants during service and recy-

cling by the filtration method. ASHRAE Transactions 94(2):2145-2151.

McCain, C.A. 1991. Refrigerant reclamation protects HVAC equipment

investment. ASHRAE Journal 33(4).

Related Commercial Resources](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ashrae2018-refrigeration-230807180745-89f60944/85/ASHRAE-2018-REFRIGERATION-pdf-141-320.jpg)

![Licensed

for

single

user.

©

2018

ASHRAE,

Inc.

Insulation Systems for Refrigerant Piping 10.5

• Cellular glass has excellent compressive strength, but it is rigid.

Density varies between 98 and 136 kg/m3, but does not greatly

affect thermal performance. It is fabricated for use on piping and

vessels. When installed on applications that are subject to exces-

sive vibration, the inner surface of the material may need to be

coated. The coefficient of thermal expansion for this material is

relatively close to that of carbon steel. When installed on refrig-

eration systems, provisions for expansion and contraction of the

insulation are usually only recommended for applications that

cycle from below-ambient to high temperatures. Cellular glass

has very low water vapor permeability and water absorption; see

information on vapor retarder systems in the section on Insulation

System Moisture Resistance.

• Flexible elastomerics are soft and flexible. This material is suit-

able for use on nonrigid tubing, and its density ranges from 48 to

136 kg/m3. Although vapor permeability can be as low as

0.146 ng/(s·Pa·m), this is still significantly higher than the per-

meance requirement for vapor retarders [1.14 ng/(s ·Pa·m2)]. For

this reason, in refrigeration piping, flexible elastomeric should be

used only with a vapor retarder applied to the exterior surface.

• Closed-cell phenolic foam insulation has a very low thermal con-

ductivity, and can provide the same thermal performance as other

insulations at a reduced thickness. Its density is 16 to 48 kg/m3.

This material also has low flammability.

• Polyisocyanurateinsulation has low thermal conductivity and ex-

cellent compressive strength. Density ranges from 29 to 96 kg/m3.

• Extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation has good compressive

strength. Typical density range is 24 to 32 kg/m3.

Insulation Joint Sealant/Adhesive

All insulation materials that operate in below-ambient conditions

should be protected by a continuous vapor retarder system. Joint seal-

ants contribute to the effectiveness of this system. The sealant should

resist liquid water and water vapor, and should bond to the specific

insulation surface. The sealant should be applied at all seams, joints,

terminations, and penetrations to retard transfer of water and water

vapor into the system.

Vapor Retarders

Insulation materials should be protected by a continuous vapor

retarder system with a maximum permeance of 1.14 ng/(s ·Pa·m2),

either integral to the insulation or as a separate vapor retarder mate-

rial applied to the exterior surface of the insulation. At operating

temperatures below –18°C, strongly consider requiring the vapor

retarder to have a maximum permeance of 0.57 ng/(s·Pa·m2).

Service life of the insulation and pipe depends primarily on the

installed water vapor permeance of the system, comprised of the

permeance of the insulation, vapor retarders on the insulation, and

the sealing of all joints, seams, and penetrations. Therefore, the

vapor retarder must be free of discontinuities and unsealed

penetrations. It must be installed to allow expansion and contrac-

tion without compromising the vapor retarder’s integrity. The

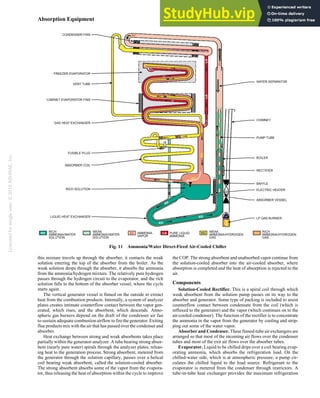

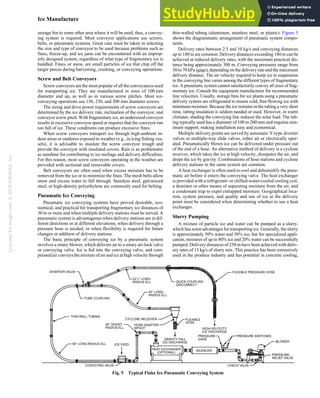

Table 3 Cellular Glass Insulation Thickness for

Indoor Design Conditions, mm

(32°C Ambient Temperature, 80% Relative Humidity,

0.9 Emittance, 0 km/h Wind Velocity)

Nominal Pipe

Size, mm

Pipe Operating Temperature, °C

+4 –7 –18 –29 –40 –51 –62 –73

15 25 40 40 50 50 65 65 65

20 40 40 50 50 65 65 65 75

25 25 40 50 50 65 65 75 75

40 40 40 50 50 65 65 75 75

50 40 50 50 65 65 75 90 90

65 40 40 50 65 65 75 75 90

75 40 50 65 65 75 90 90 100

100 40 50 65 75 75 90 90 100

125 40 50 65 75 75 90 100 100

150 40 50 65 75 90 90 100 100

200 40 50 65 75 90 100 100 115

250 40 50 65 75 90 100 115 115

300 40 50 65 75 90 100 115 125

350 50 65 75 90 100 115 115 125

400 50 65 75 90 100 115 115 125

450 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 125

500 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

600 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

700 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

750 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

900 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

Vert Flat 50 65 90 100 115 125 150 165

Tk Top 50 65 90 100 115 125 150 165

Tk Bot. 50 65 90 100 115 125 150 165

Notes:

1. Insulation thickness shown is that required to prevent condensation on outside jacket

surface or limit heat gain to 25 W/m2, whichever thickness is greater, at the condi-

tions specified.

2. Thicknesses shown are applicable only to the conditions specified. Changing any

condition, even slightly, can influence the required thickness.

3. All thicknesses are in millimetres.

4. Values do not include safety factor. Actual operating conditions may vary. Consult a

design engineer for appropriate recommendation for the specific system.

5. Thickness calculated using ASTM Standard C680-14 methodology.

Table 4 Cellular Glass Insulation Thickness for

Outdoor Design Conditions, mm

(38°C Ambient Temperature, 94% Relative Humidity,

0.1 Emittance, 12 km/h Wind Velocity)

NominalPipe

Size, mm

Pipe Operating Temperature, °C

+4 –7 –18 –29 –40 –51 –62 –73

15 40 40 50 65 65 65 75 75

20 40 50 50 65 65 75 75 90

25 40 50 50 65 75 90 90 100

40 40 50 65 65 75 90 100 100

50 50 65 75 75 90 100 115 125

65 40 50 65 75 90 100 115 125

75 50 65 75 90 100 115 125 140

100 65 75 90 100 115 125 140 150

125 65 75 100 115 125 140 150 165