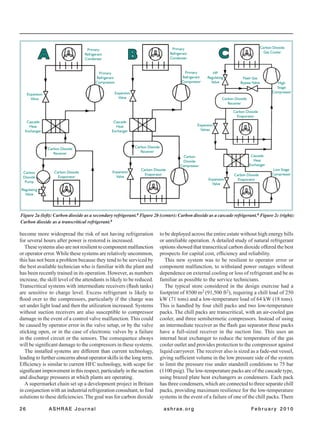

This document summarizes the history and development of using carbon dioxide as a refrigerant in supermarket refrigeration systems. It describes early trials using carbon dioxide in the 1990s in Europe, as well as different system configurations that have been used, including secondary loops, cascade systems, and transcritical direct systems. The document then presents a new system design for using carbon dioxide across an entire supermarket estate that aims to improve reliability, efficiency, and resilience to power outages or component failures. A test unit of this new design was constructed in 2008 in England.