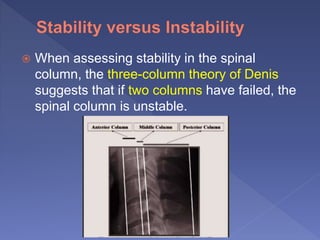

This document discusses spinal trauma, with a focus on cervical spine injuries. It provides details on:

- Epidemiology of spinal cord injuries and common causes

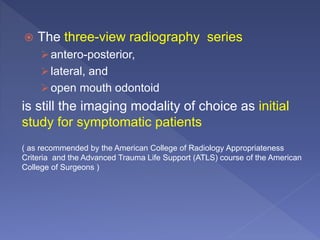

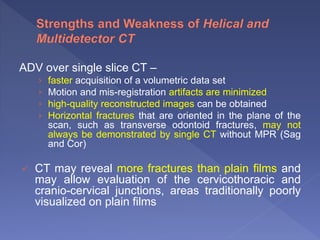

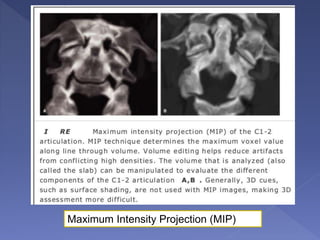

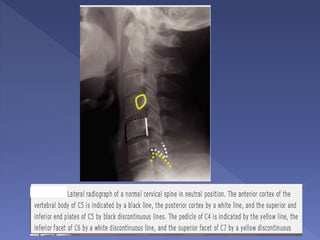

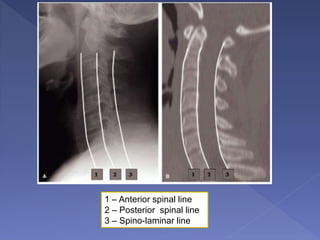

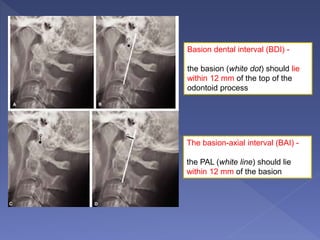

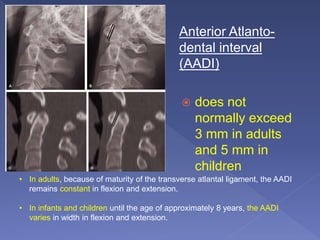

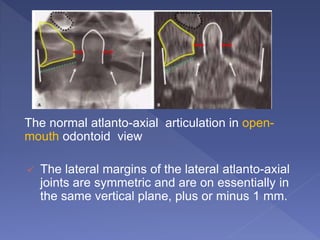

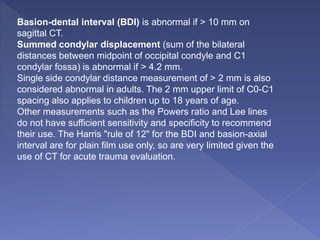

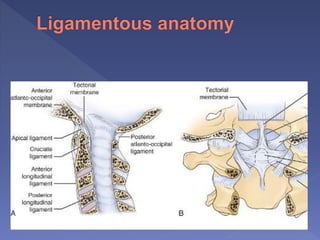

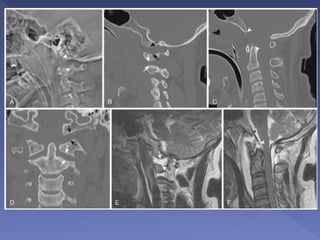

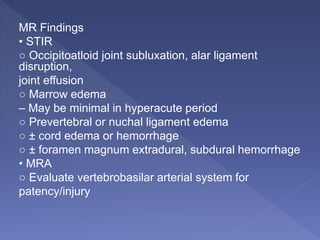

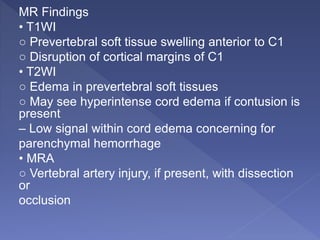

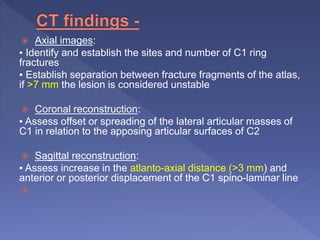

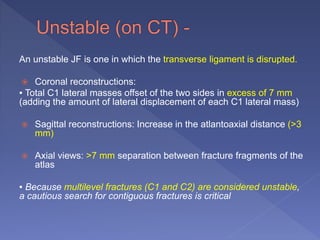

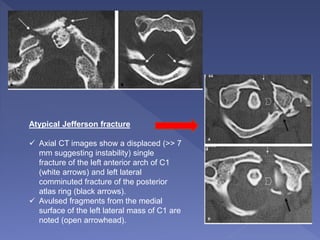

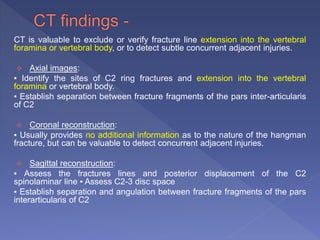

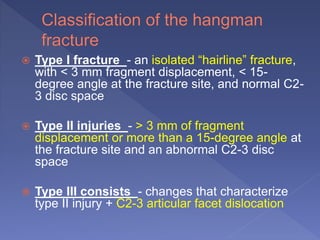

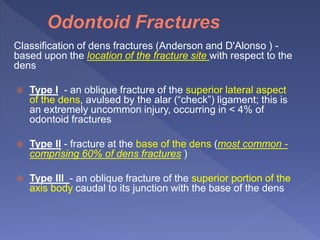

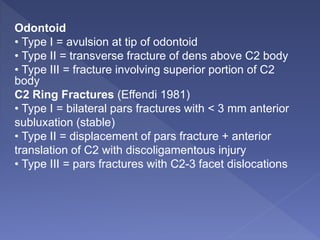

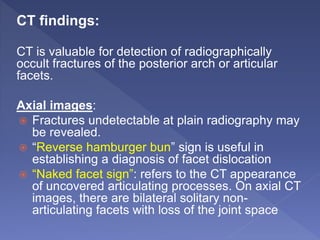

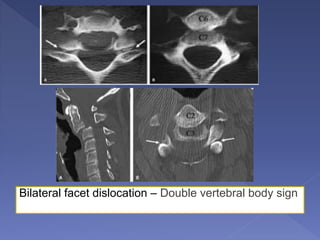

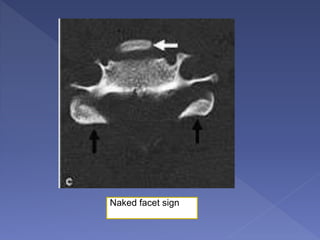

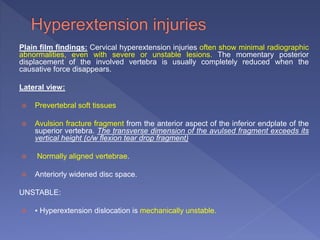

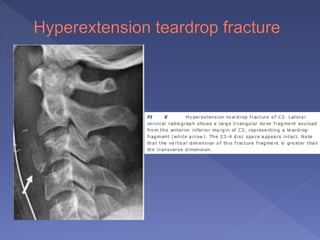

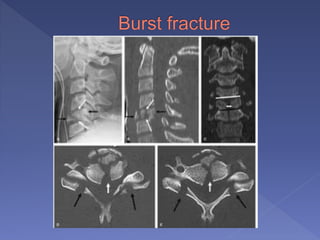

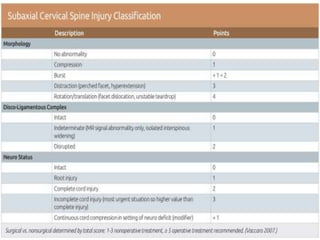

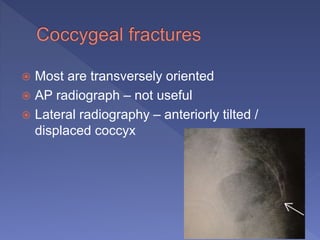

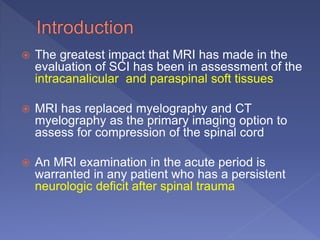

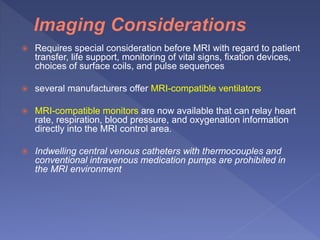

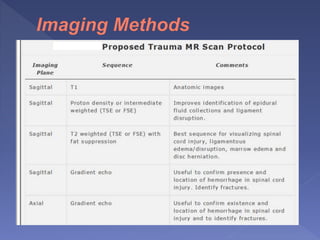

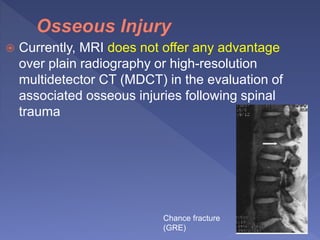

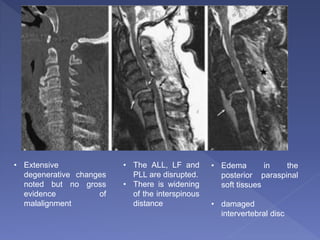

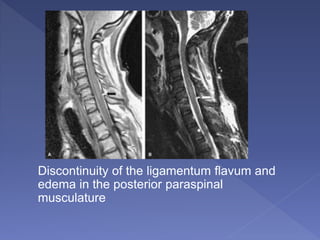

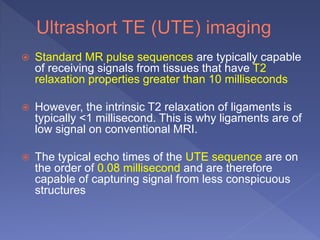

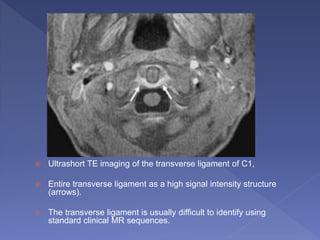

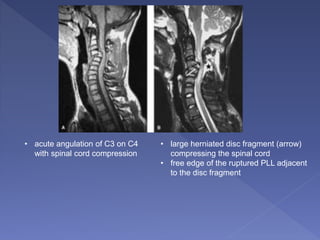

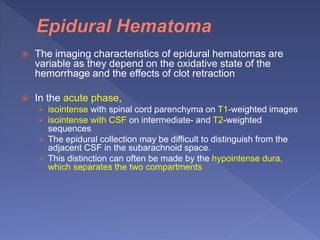

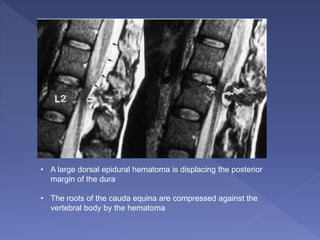

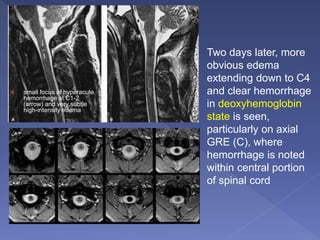

- Imaging techniques used to evaluate spinal trauma, including radiography, CT, MRI

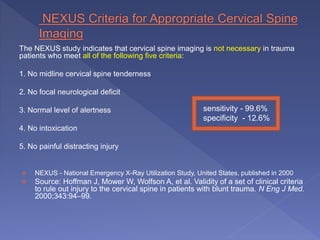

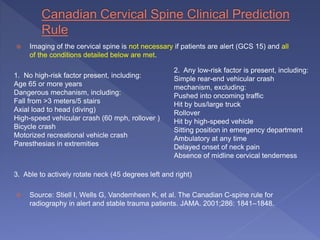

- Clinical criteria like NEXUS and Canadian C-Spine Rule that can determine if imaging is needed

- Differences in cervical spine injuries between age groups and considerations for imaging children

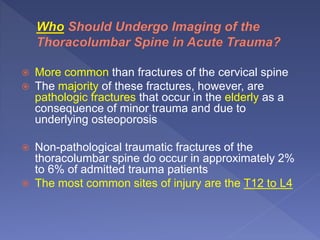

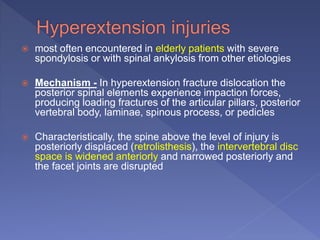

- Types of fractures more common in the elderly

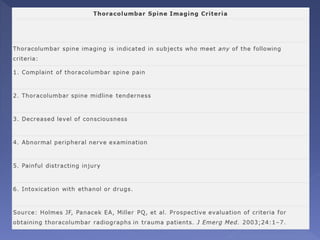

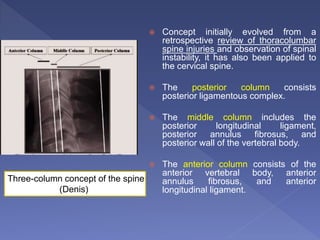

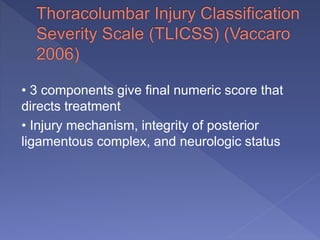

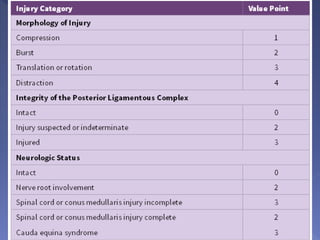

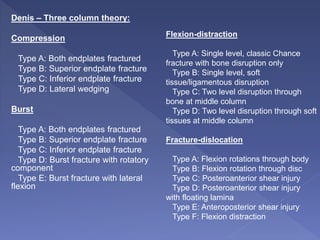

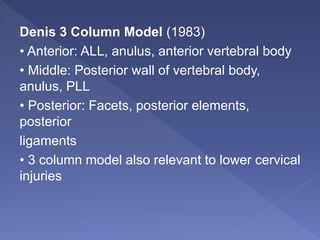

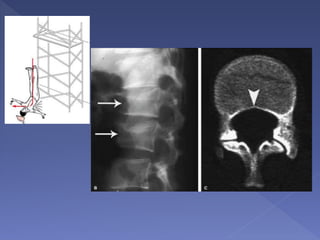

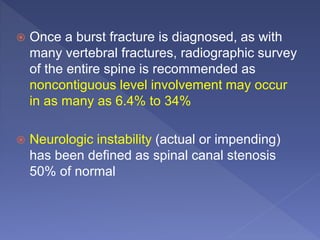

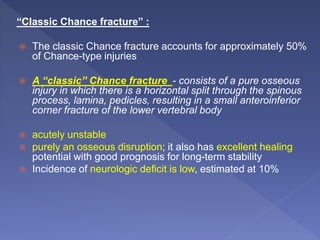

- Using CT to evaluate the thoracolumbar spine

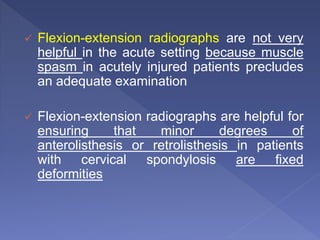

- Advantages and limitations of various imaging modalities and techniques