1. Microcytic anemia can be identified by a low MCV on a CBC, small RBCs on a blood smear, or an increased RDW. The most common causes are iron deficiency anemia and thalassemia.

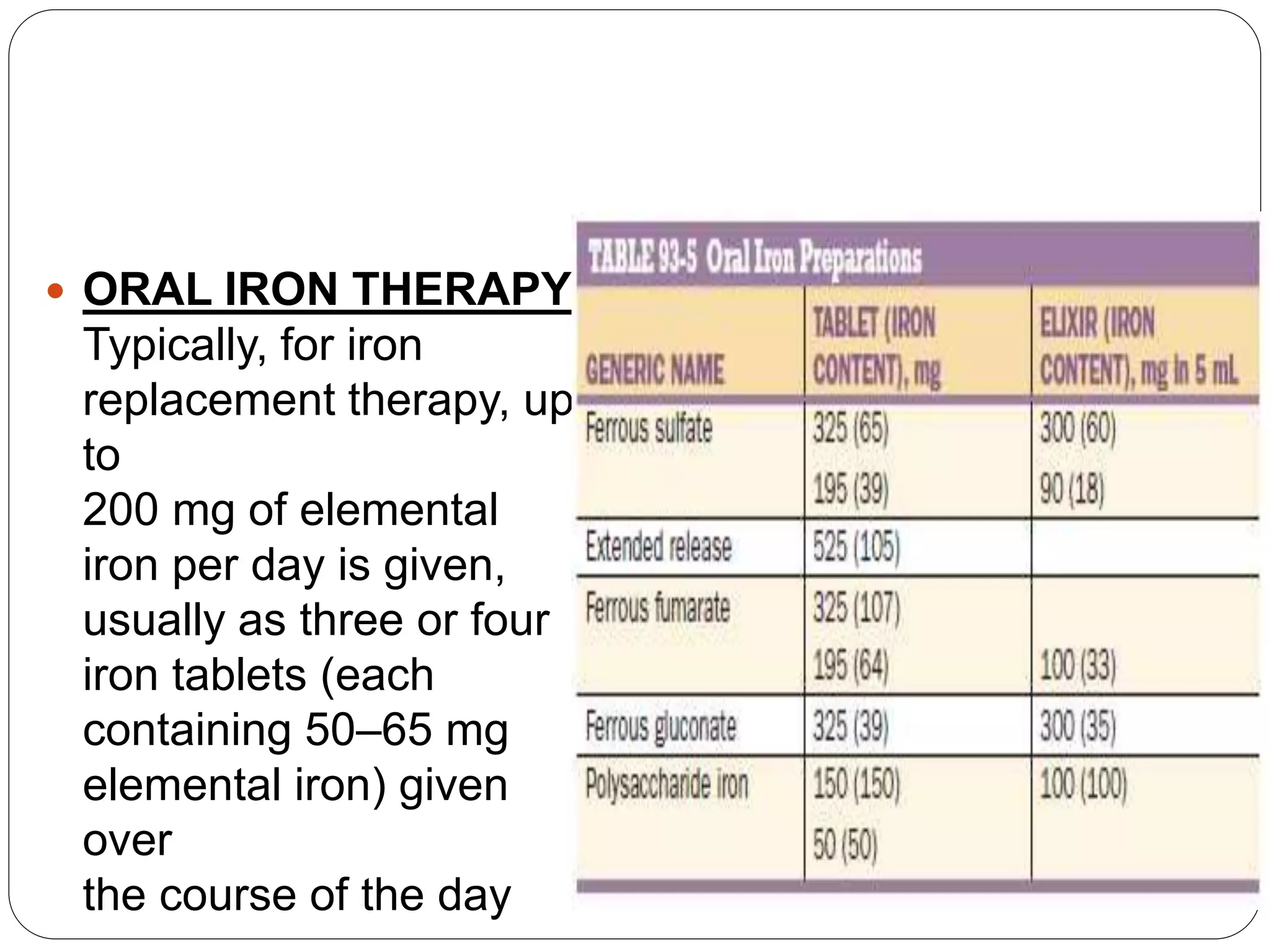

2. Iron deficiency anemia is usually caused by inadequate dietary iron intake or increased needs. It often affects young children, women, and pregnant women. Ferritin levels below 15 ng/mL indicate iron deficiency.

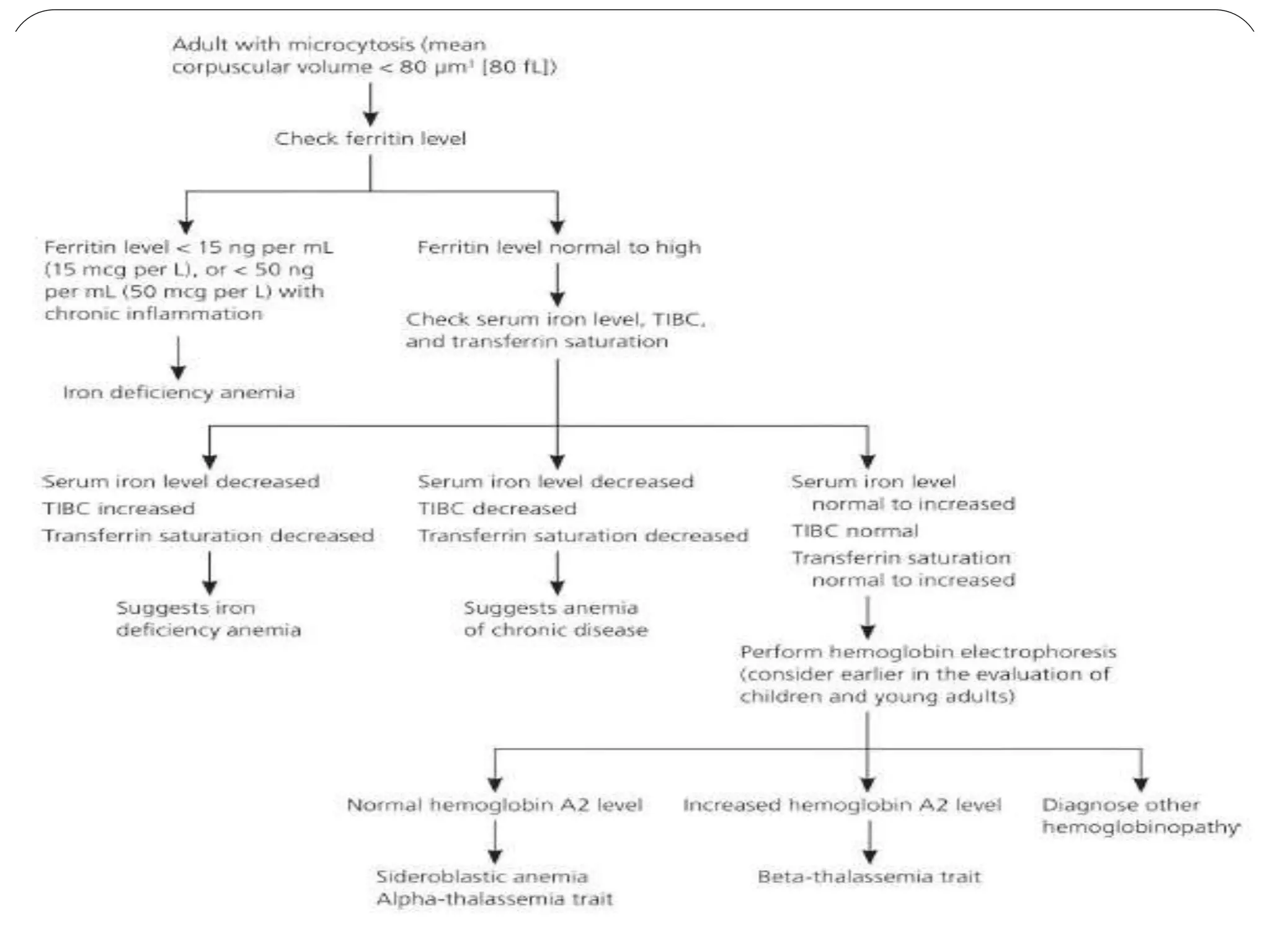

3. Thalassemia involves a genetic defect in hemoglobin production and is more common in those of Mediterranean, Southeast Asian, and African descent. Beta-thalassemia trait causes mild anemia while alpha-thalassemia trait

![Microcytosis can be documented from

1. the mean cell volume (MCV) on an automated hematology instrument (ie, MCV

below 80 femtoliters [fL] for an adult or below the age-appropriate value for children) or

2. from examination of the peripheral blood smear. Variation in cell size can be

assessed from the red blood cell (RBC) distribution width (RDW) or

3. from observing the degree of anisocytosis on the blood smear.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/approachtomicrocyticanemia-200827155645/75/Approach-to-microcytic-anemia-2-2048.jpg)

![THALASSEMIA:-

Most patients with beta-thalassemia trait have mild

anemia (hemoglobin level is rarely less than 9.3 g per

dL [93 g per L]).

In addition, the mean corpuscular volume can

sometimes reach much lower levels than with iron

deficiency anemia alone.

Ultimately, the diagnosis of beta-thalassemia trait is

made when hemoglobin electrophoresis shows a

slight increase in hemoglobin A2.

Coexisting iron deficiency anemia can lower

hemoglobin A2 levels; therefore, iron deficiency

anemia must be corrected before hemoglobin

electrophoresis results can be appropriately

evaluated.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/approachtomicrocyticanemia-200827155645/75/Approach-to-microcytic-anemia-7-2048.jpg)