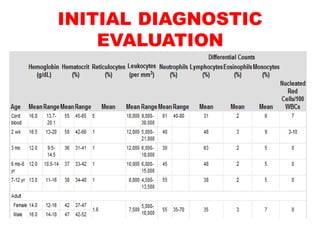

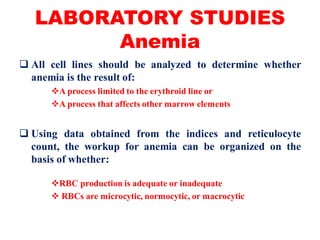

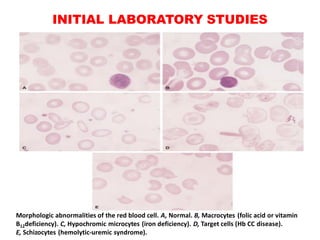

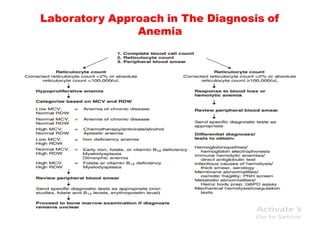

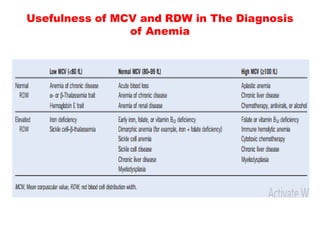

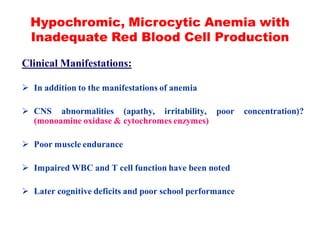

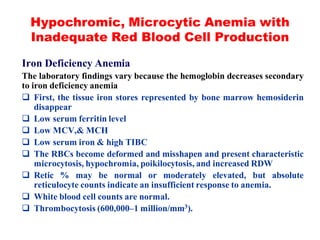

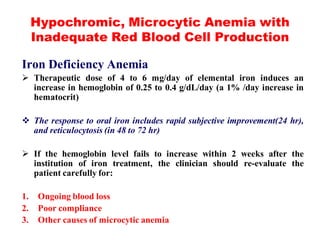

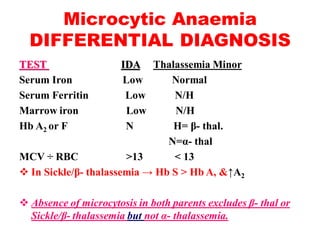

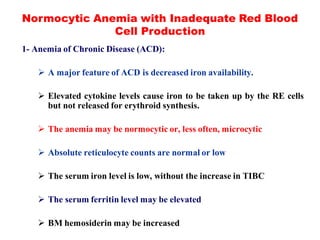

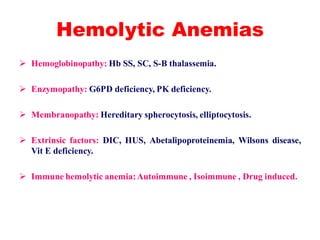

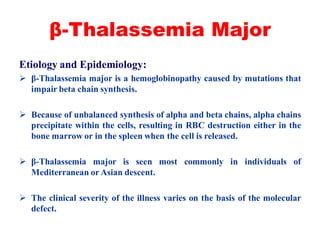

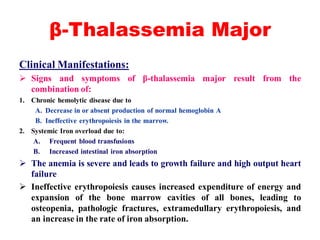

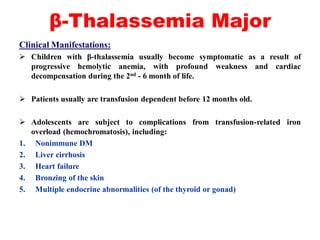

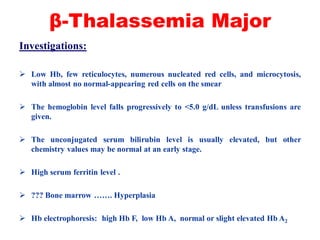

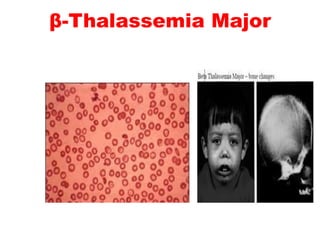

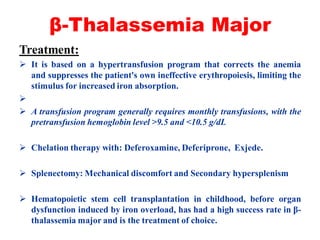

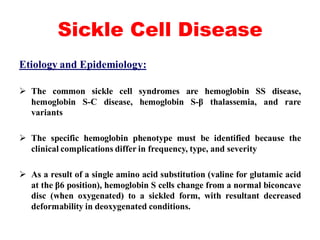

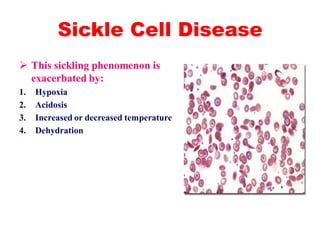

The document discusses the evaluation and diagnosis of pediatric blood disorders. It notes that the history, physical exam, and initial laboratory tests provide clues to diagnose blood diseases. Diagnosis requires knowledge of normal hematological values that vary by age. The initial workup involves tests like hemoglobin, red blood cell indices, blood smear exam. Further tests are used depending on the results to diagnose causes like anemia, hemolytic disorders, and hemoglobinopathies. Specific disorders discussed in more detail include iron deficiency anemia, thalassemias, sickle cell disease, and their typical laboratory findings and treatment approaches.