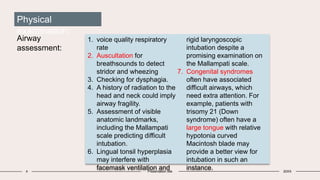

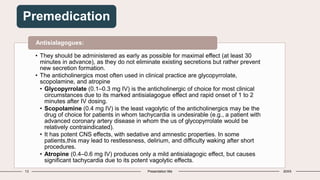

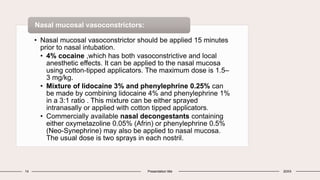

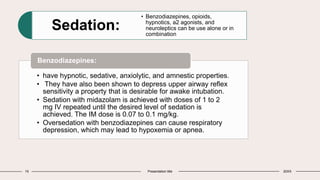

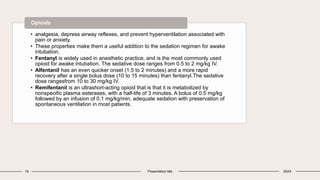

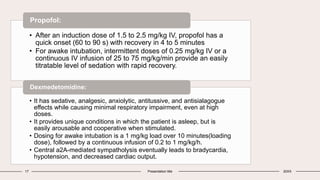

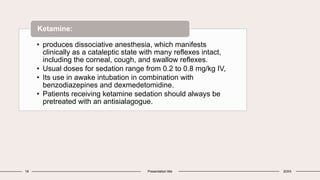

This document discusses anesthesia considerations for ENT surgeries. It ranges from simple procedures like myringotomies to more complex cases involving airway manipulation or reconstruction. Proper pre-operative evaluation is important to assess any risk factors for a difficult airway. Various anesthesia techniques are described including general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway devices, intermittent apnea, or local anesthesia with sedation. Preparation and equipment for awake fiberoptic intubation is outlined, including premedication, topicalization, and sedation options to balance patient comfort and airway protection.

![Anaesthetic management in Otolaryngology

6 Presentation title 20XX

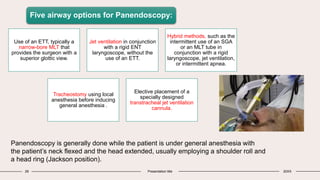

The following general management options exist

(1)general endotracheal anesthesia

(2) general anesthesia using a supraglottic airway (SGA) device (e.g., laryngeal mask airway

[LMA])

(3) general anesthesia using an ENT laryngoscope (to expose the airway) in conjunction with

jet ventilation;

(4) use of intermittent apnea

(5) general anesthesia using the patient’s natural airway, with or without adjuncts such as jaw

positioning devices or nasopharyngeal airways.

(6) local anesthesia in conjunction with intravenous sedation, with the patient breathing

spontaneously.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anesthesiaforentsurgeries2-230904123658-341056f7/85/Anesthesia-for-ENT-surgeries-2-pptx-6-320.jpg)

![25 Presentation title 20XX

LUDWIG ANGINA

• Ludwig angina is a multispace infection of the floor of

the mouth. The infection usually starts with infected

mandibular molars and spreads to submandibular,

sublingual, submental, and buccal spaces.

• The tongue becomes elevated and displaced

posteriorly, which may lead to loss of the airway,

especially when the patient is in the supine position.

Airway

management

• Depend on clinical severity, imaging findings (e.g.,

computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance

imaging [MRI] findings), and surgical preferences.

• Elective tracheostomy before incision and drainage

remains a classic.

• Ludwig angina is often associated with trismus, nasal

fiberoptic intubation is frequently needed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anesthesiaforentsurgeries2-230904123658-341056f7/85/Anesthesia-for-ENT-surgeries-2-pptx-25-320.jpg)