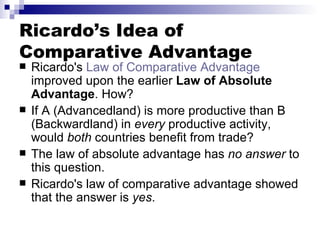

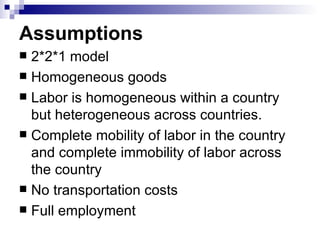

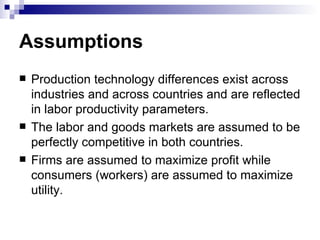

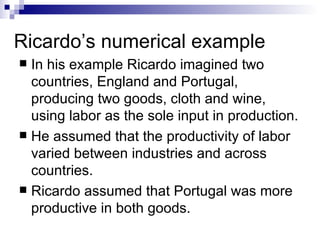

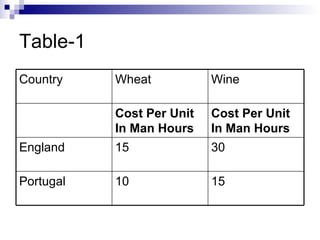

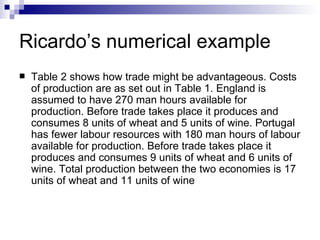

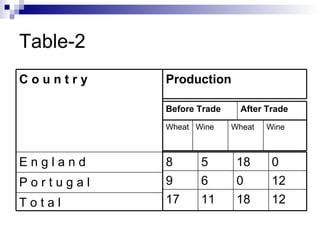

The document summarizes David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage from 1817. It explains that Ricardo formalized the idea that countries can benefit from trade even if one country is more productive in all areas. Ricardo used a numerical example to show that if countries specialize in their comparative advantage goods, where their productivity is relatively higher, then total production can increase. The theory assumes differences in productivity across countries and industries and argues countries should allocate resources to comparative advantage industries to maximize global output through specialization and trade.