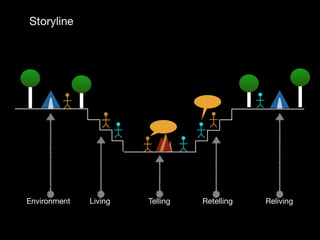

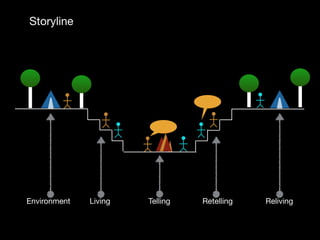

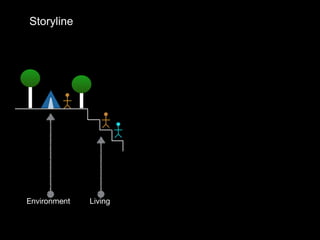

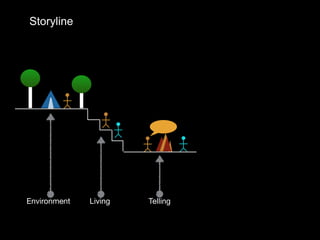

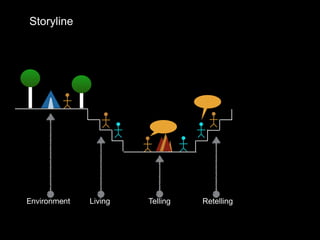

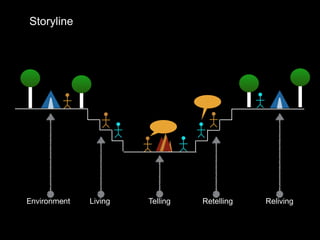

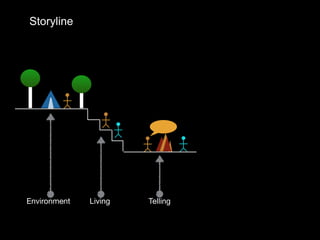

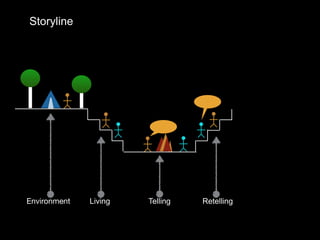

This document explores the negotiation of dominant narratives in physical education through narrative inquiry, emphasizing the significance of 'living, telling, re-telling, and re-living' personal and cultural stories. It highlights the tensions that arise as individuals' personal experiences interact with institutional and societal narratives of physical education. The work advocates for understanding these stories as a way to reshape education and create meaningful change.

![“”

“”

Talk about a battle. Yet I get the feeling that

some of the battle was with themselves

[personally] and themselves [as classes]. I

wouldn’t say that it was a success as some

lessons descended into a bit of a farce [while

others were really quite good.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/narrativeaiesep-151203231826-lva1-app6892/85/A-Narrative-Inquiry-in-physical-education-47-320.jpg)

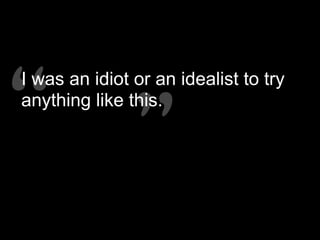

![“”

“”

This is certainly my project, as Adam [My

HOD] couldn’t give a shit. In investing

nothing in the project, beyond his ‘trust’ in

me, and making little or no effort to learn

what I’m doing and why I think it’s important,

then he places the responsibility squarely on

me and my shoulders.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/narrativeaiesep-151203231826-lva1-app6892/85/A-Narrative-Inquiry-in-physical-education-50-320.jpg)