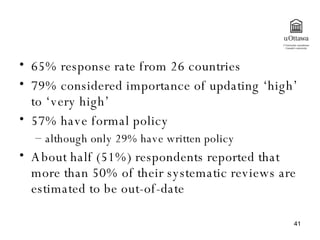

This document summarizes key points from a presentation on improving the quality of systematic reviews. It discusses issues like selective reporting of outcomes, non-publication of reviews, lack of registration, and the need for funders to improve reporting guidelines and develop templates for reviews. It also presents results from studies showing most reviews are not updated and estimating the time needed to update reviews is around 5 years. Surveys found many organizations see updating as important but few have formal policies for it.