- The document discusses various matrix operations including transpose, addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication, matrix multiplication, matrix-vector products, and finding the inverse of a matrix.

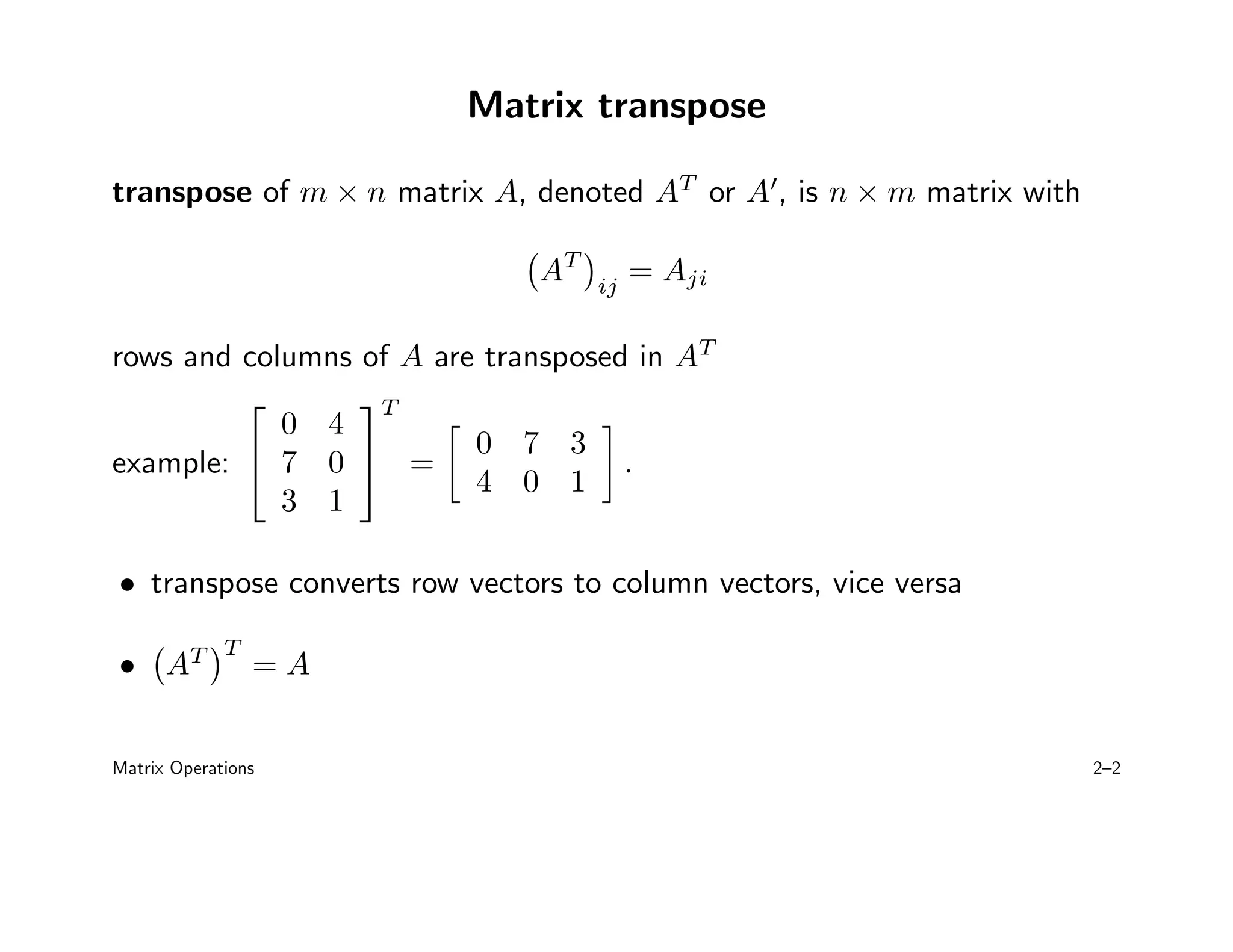

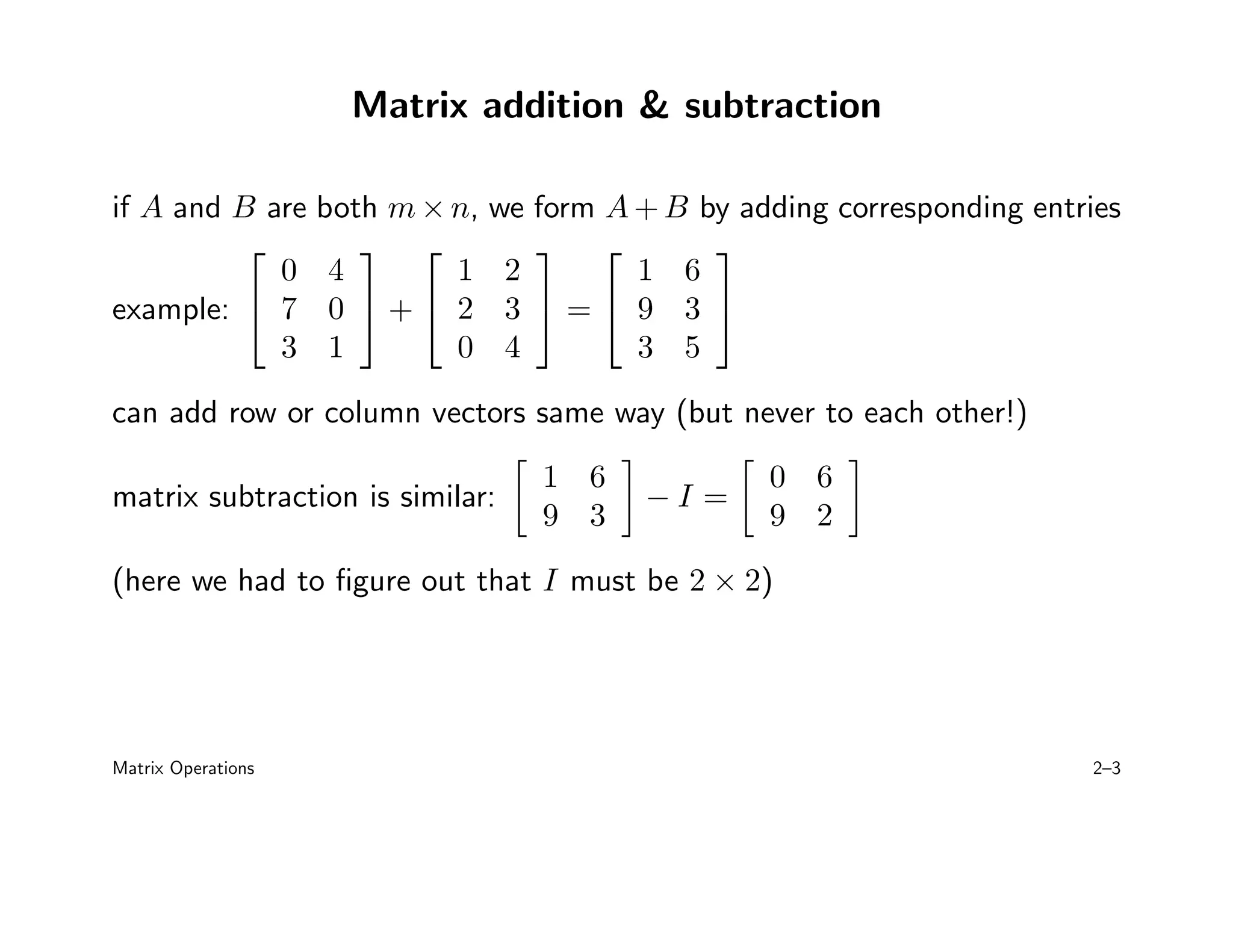

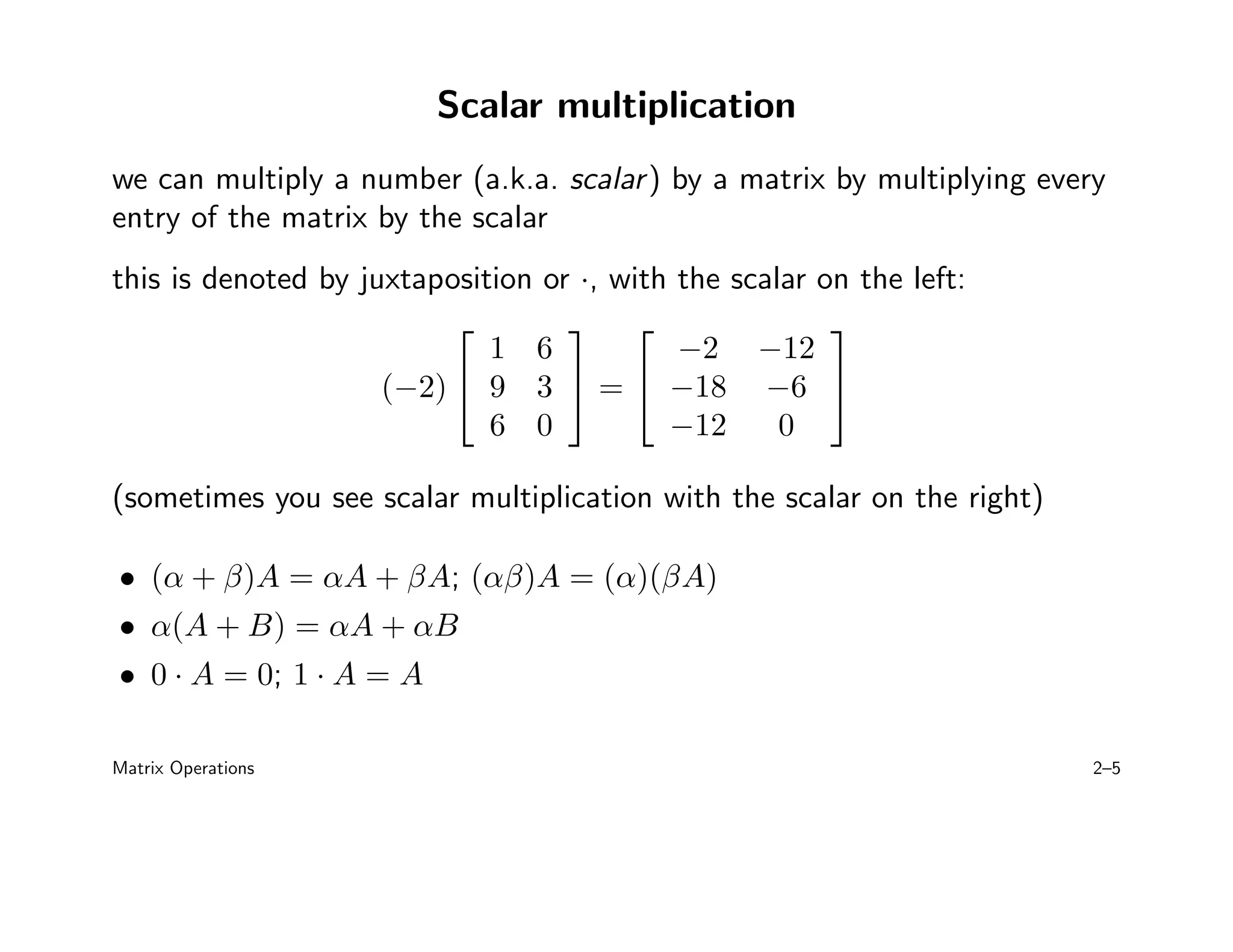

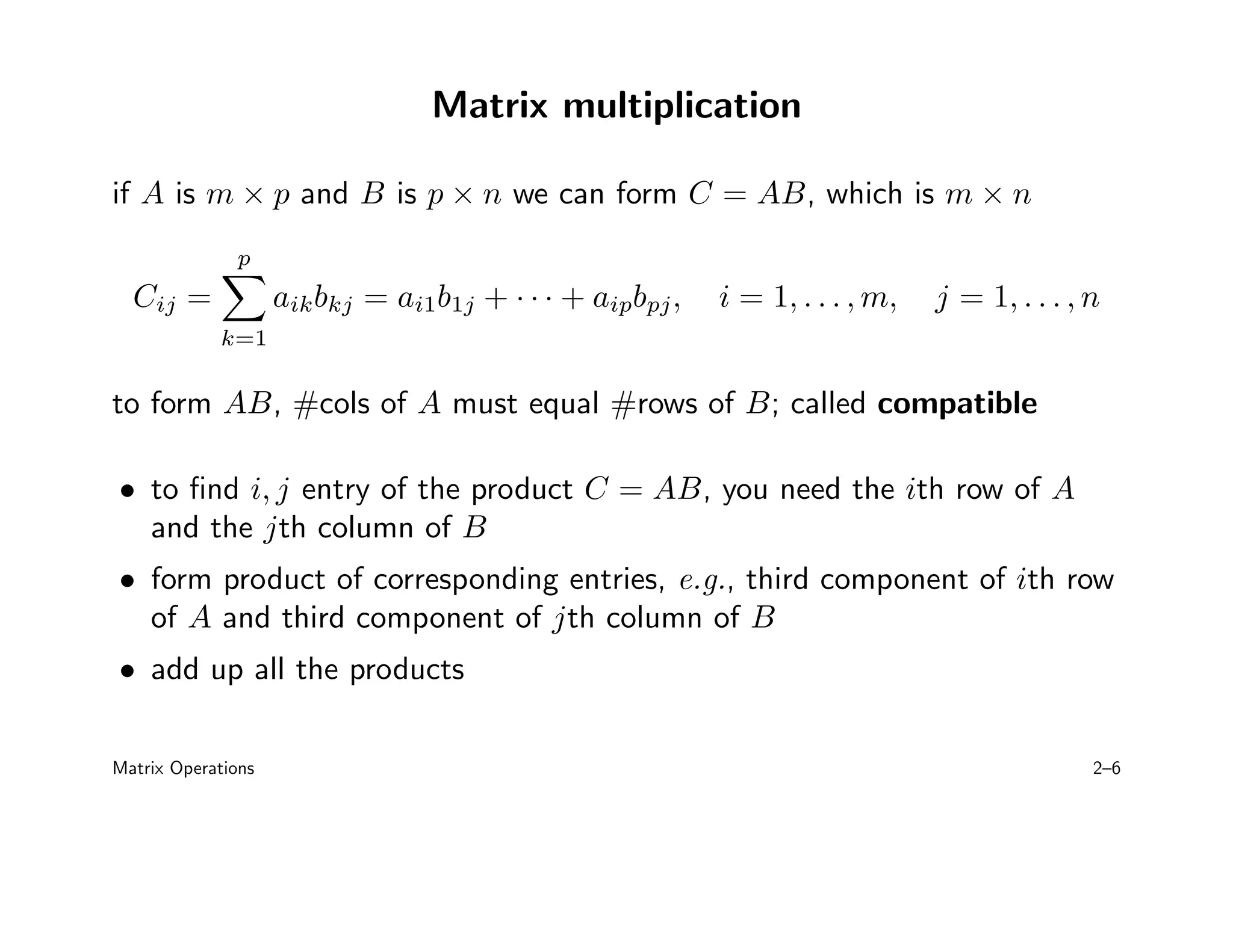

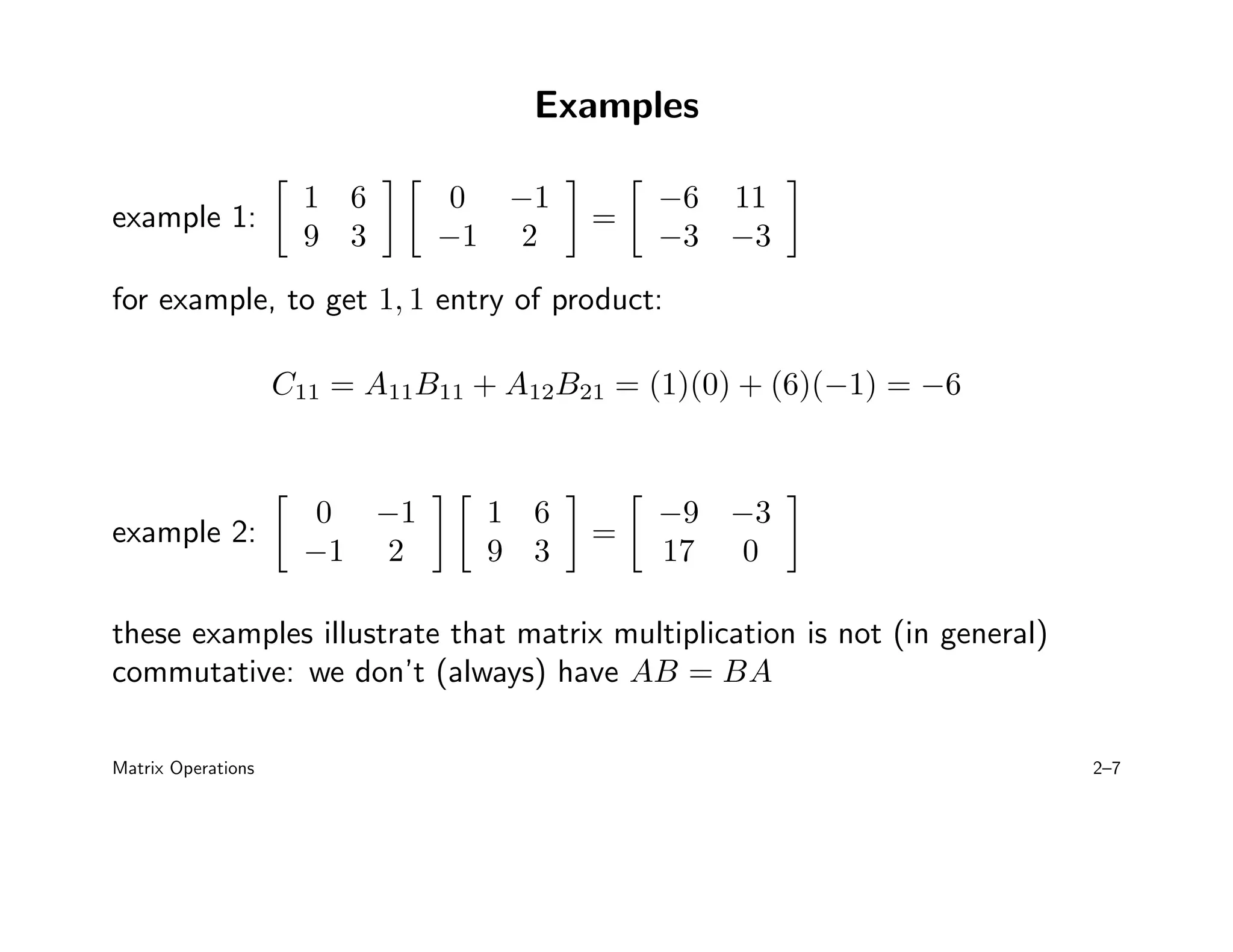

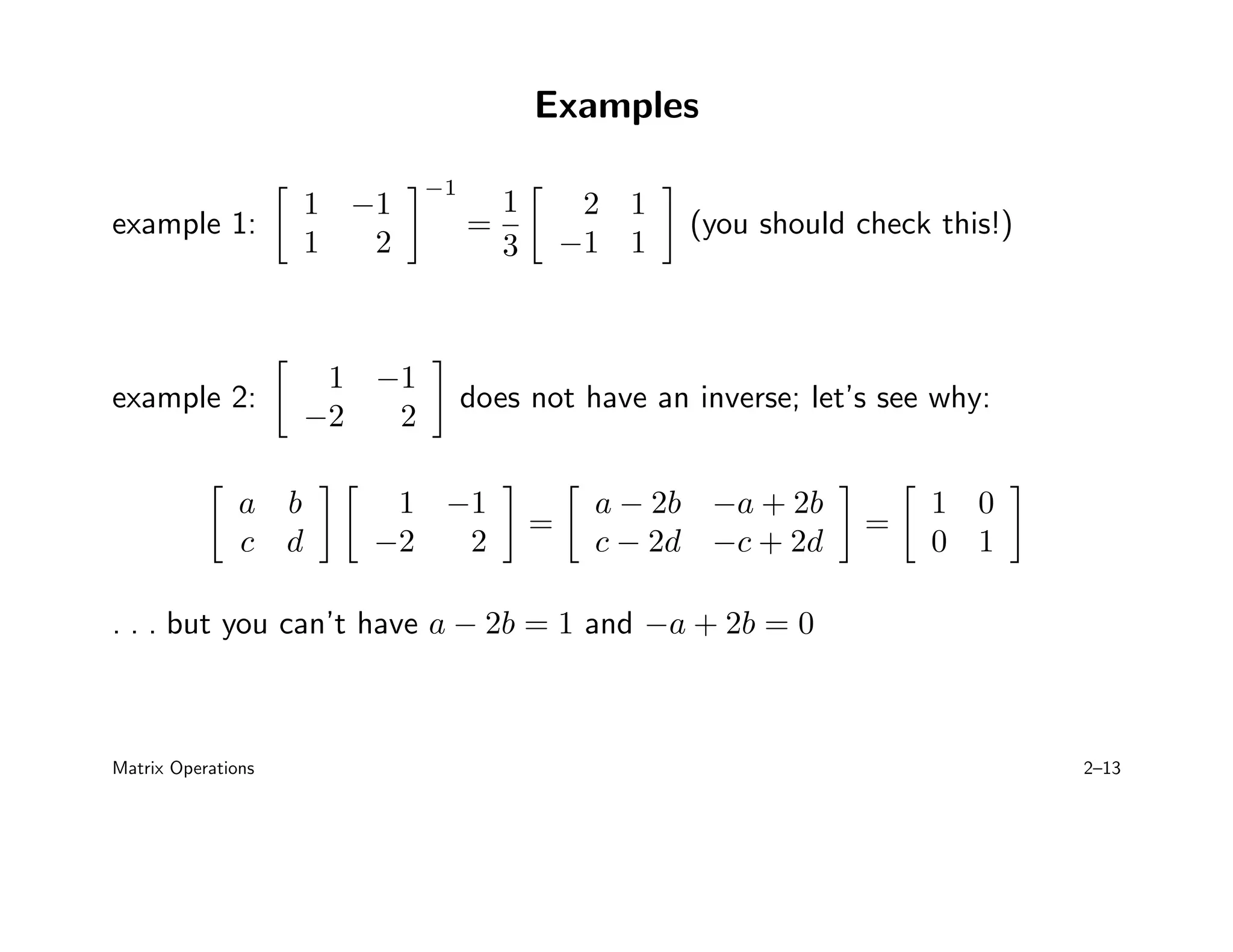

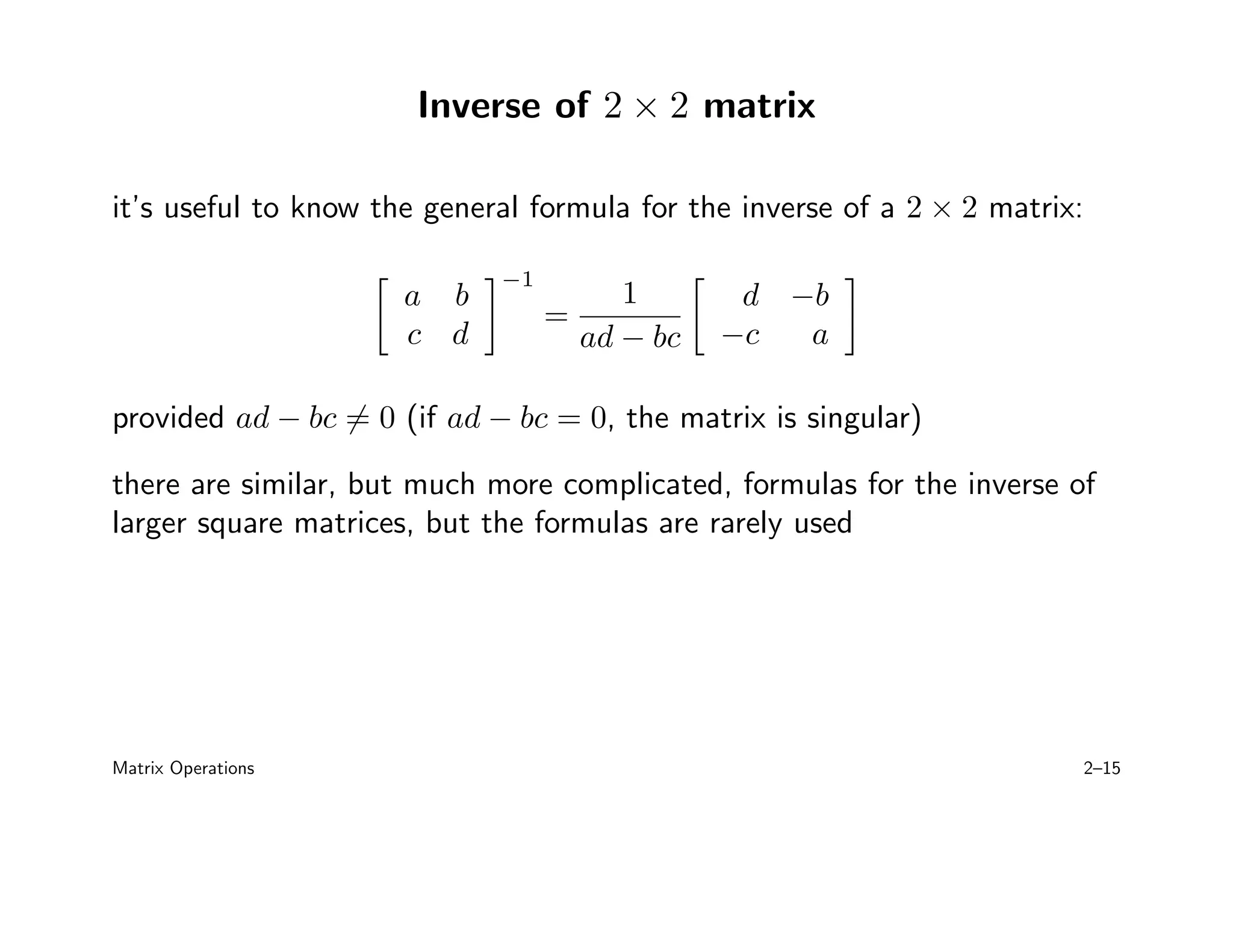

- Key operations include transposing a matrix, adding and subtracting matrices of the same size, multiplying a matrix by a scalar, multiplying two matrices if they are compatible in size, and taking the inverse of a square matrix if it exists.

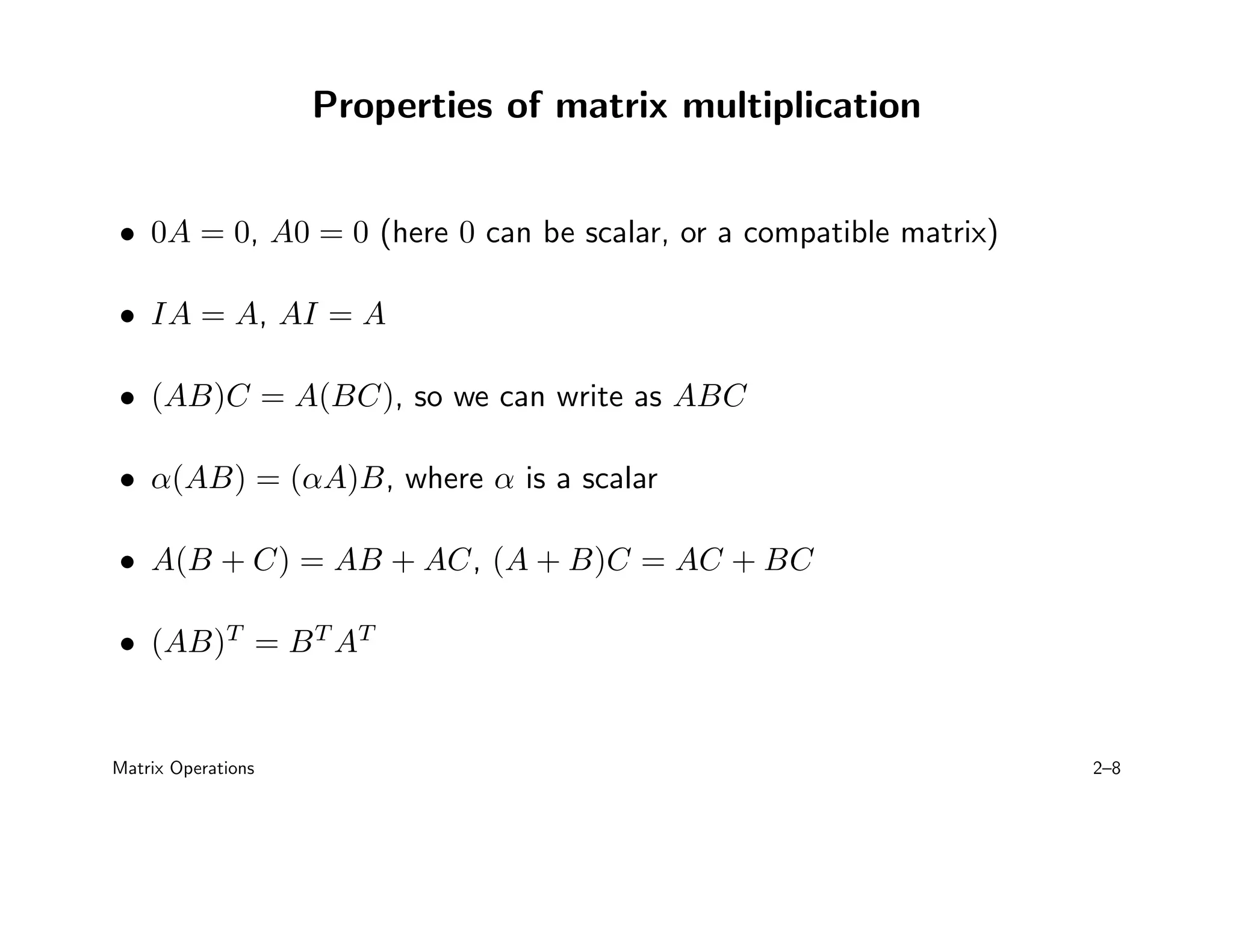

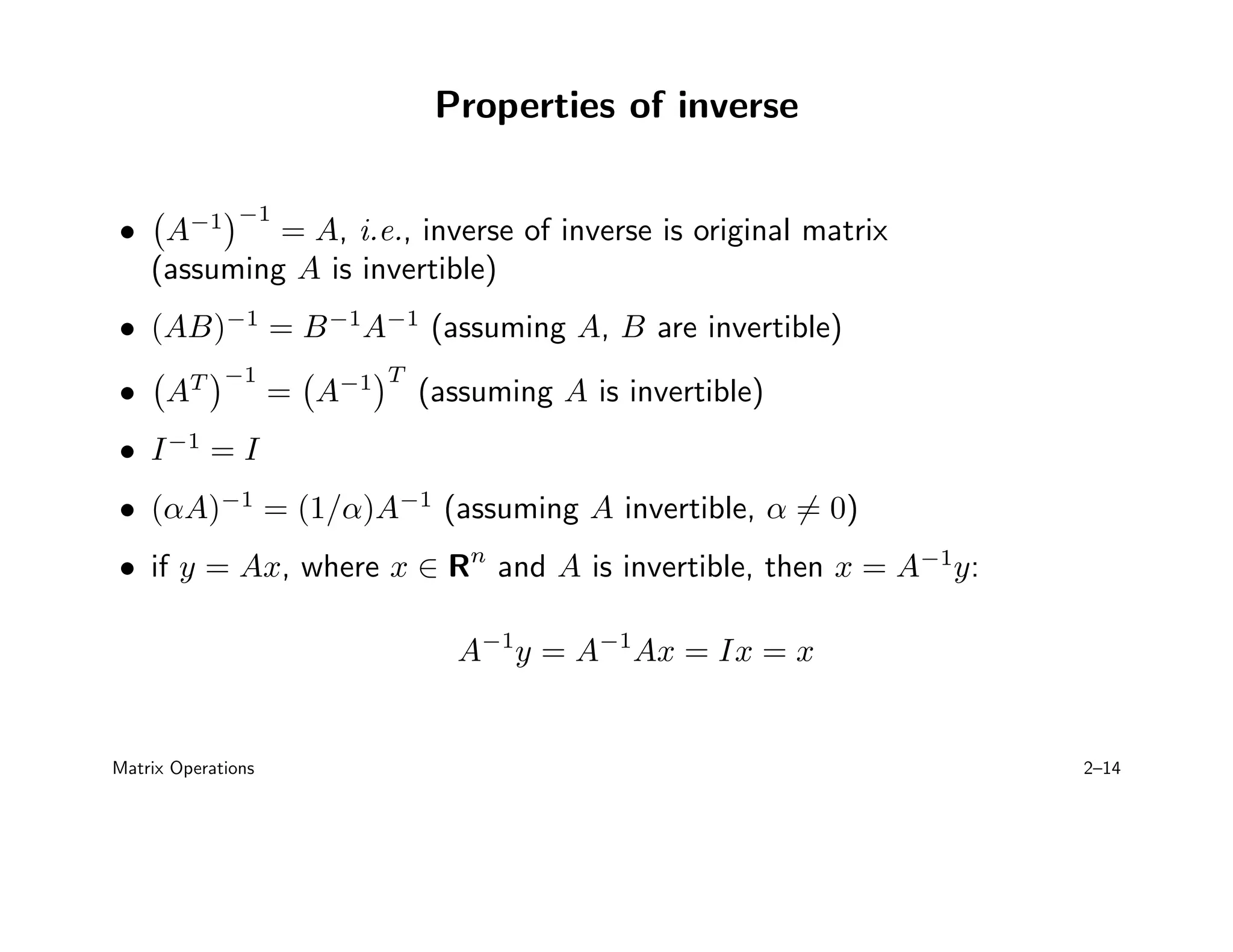

- Properties such as commutativity, associativity, and how they apply to different matrix operations are also covered.