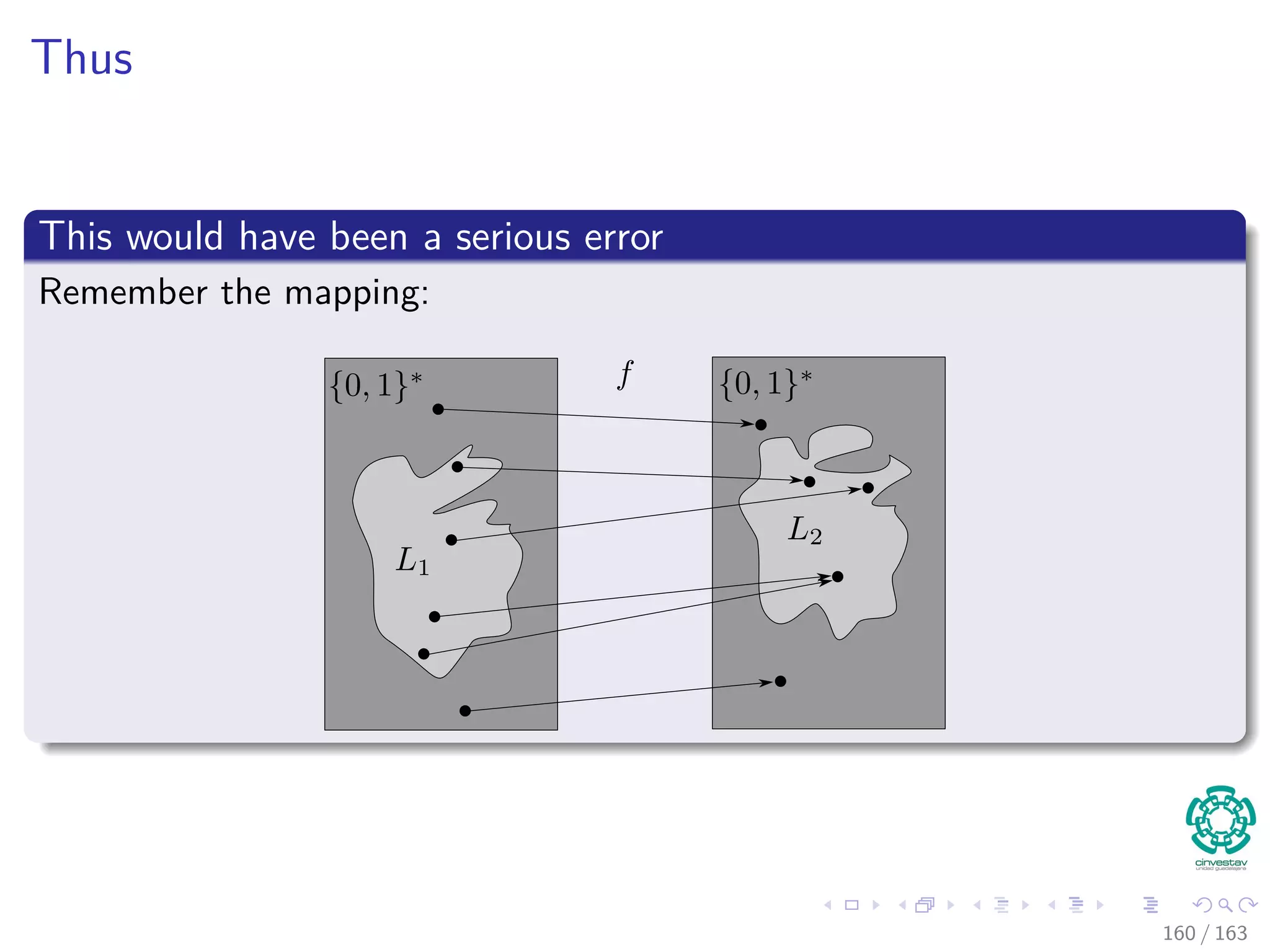

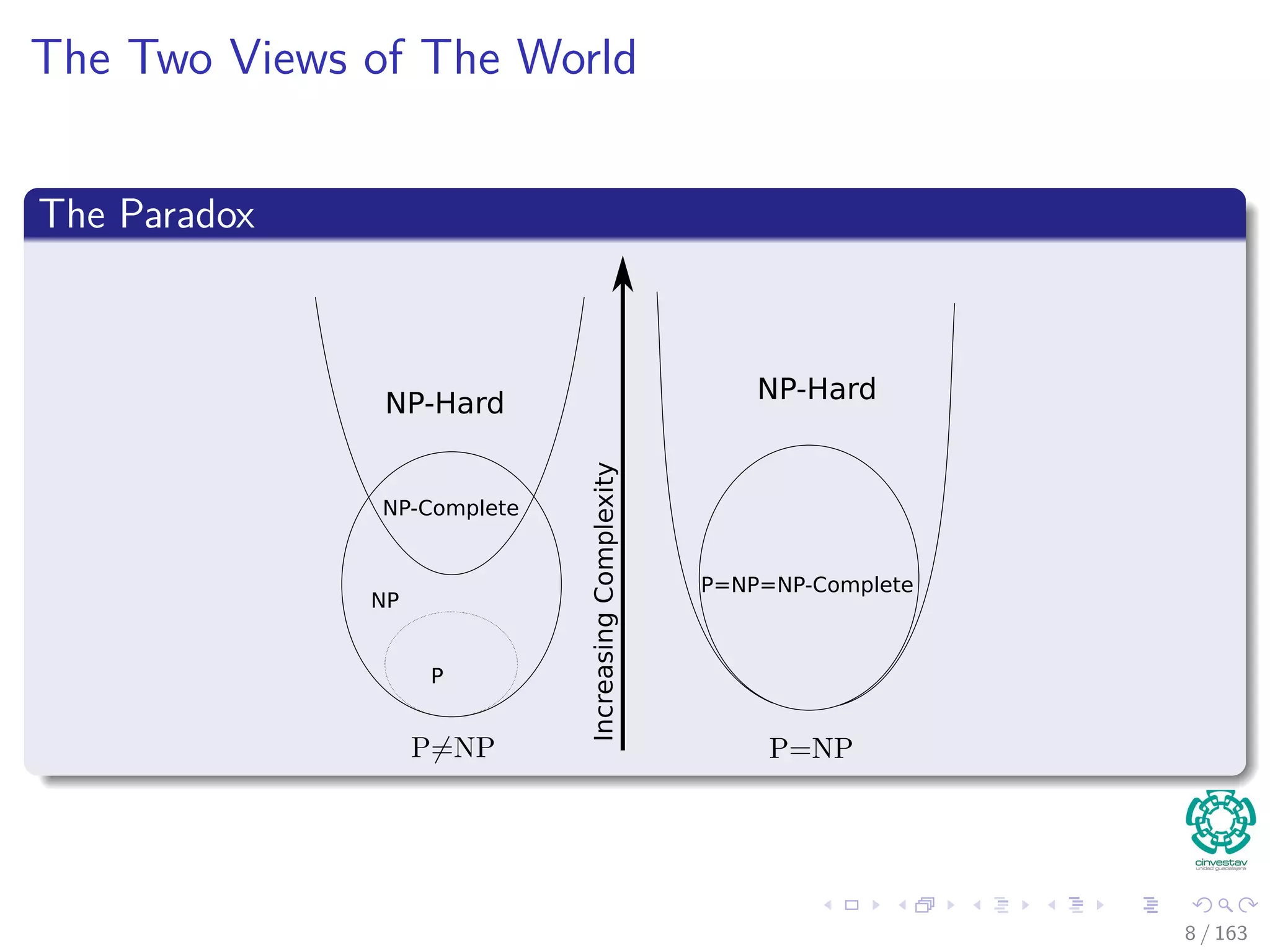

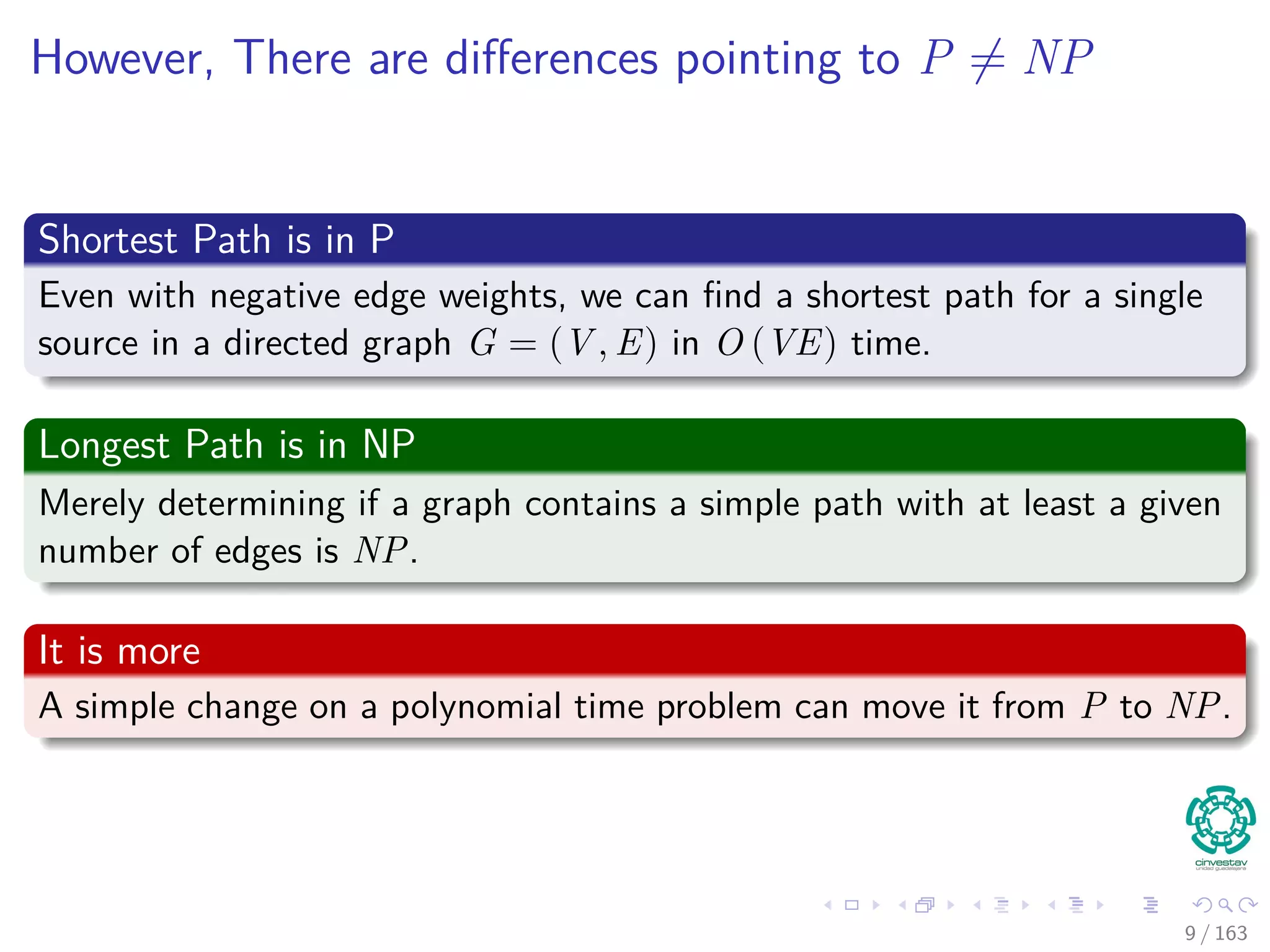

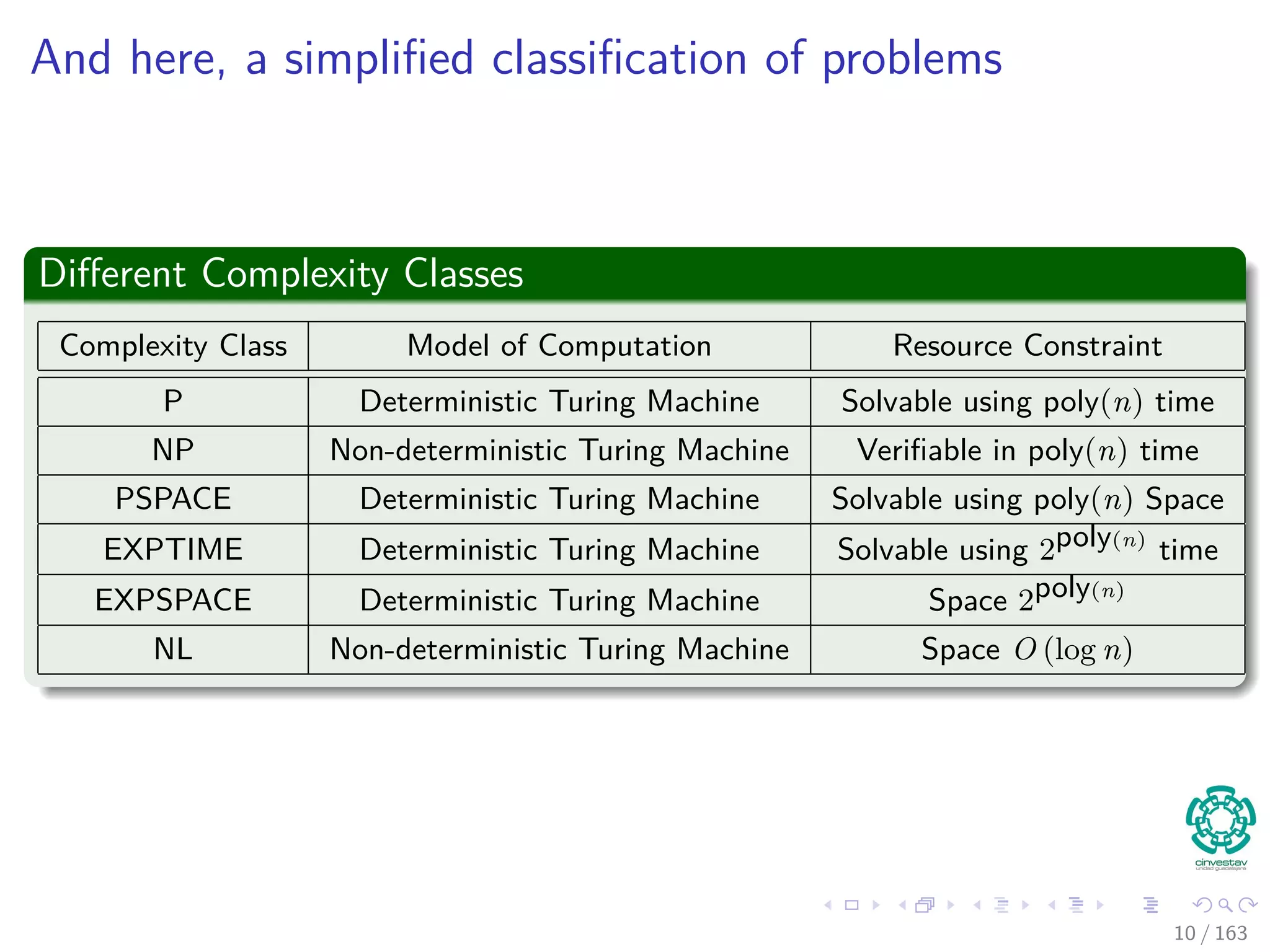

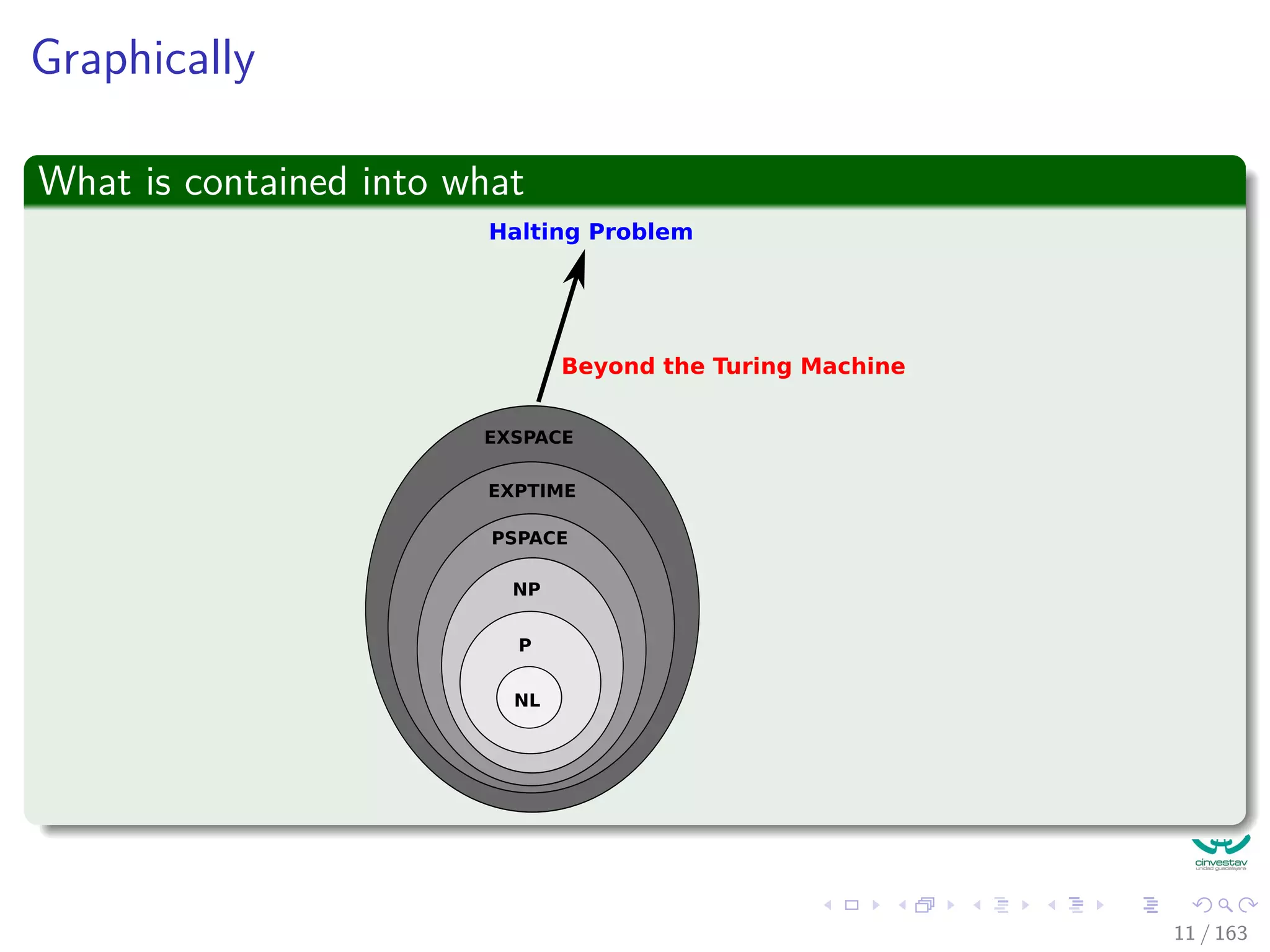

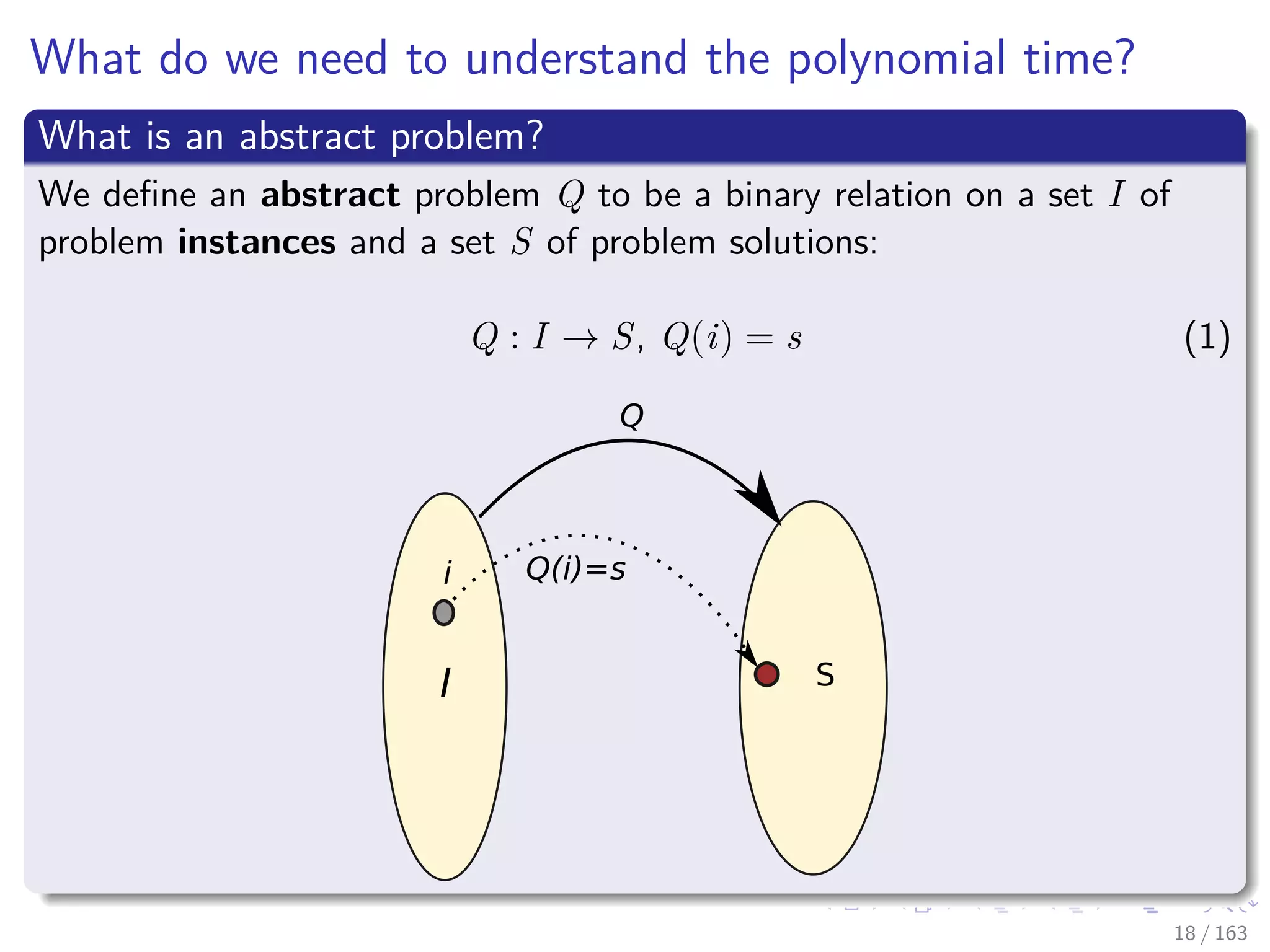

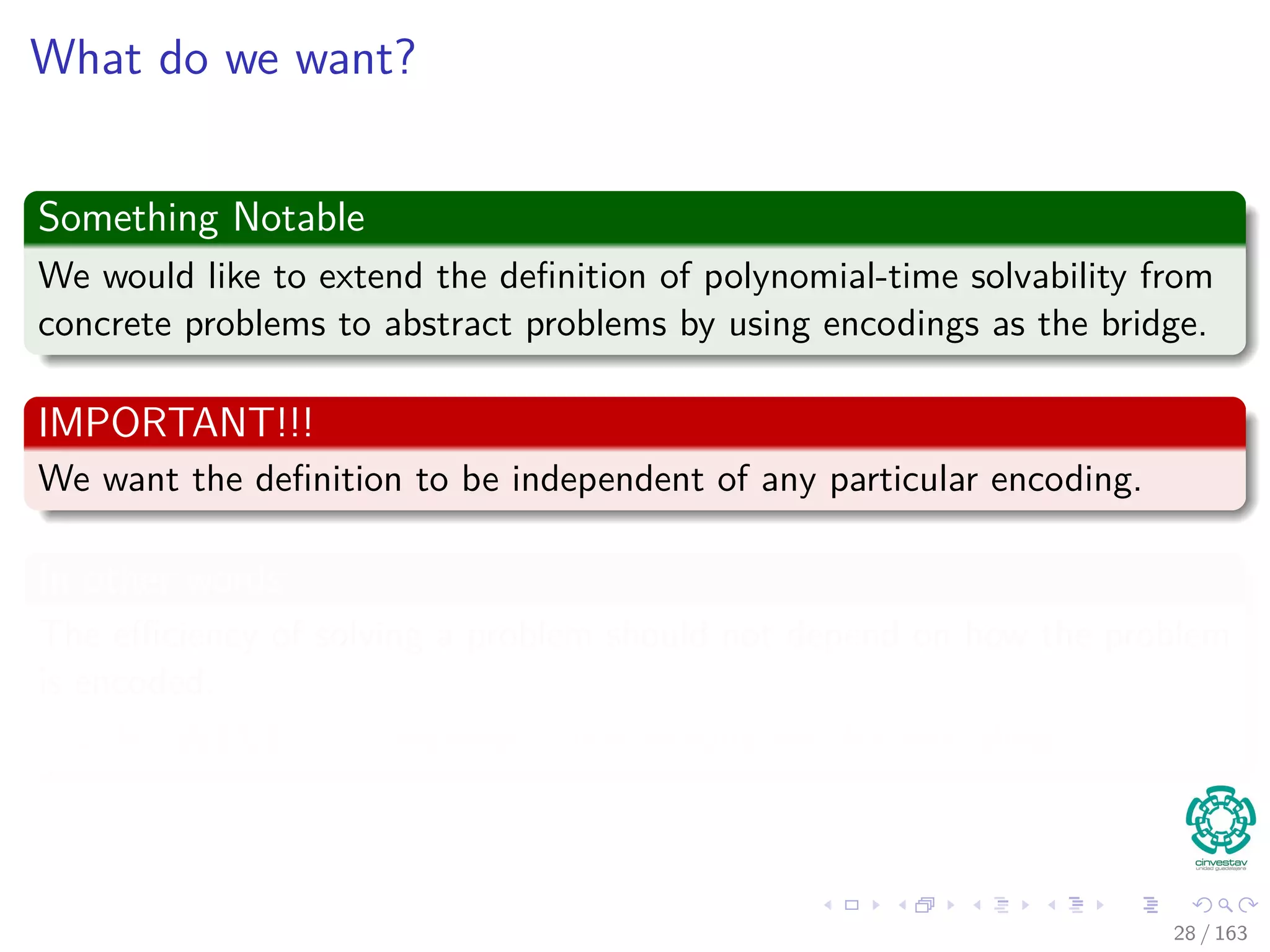

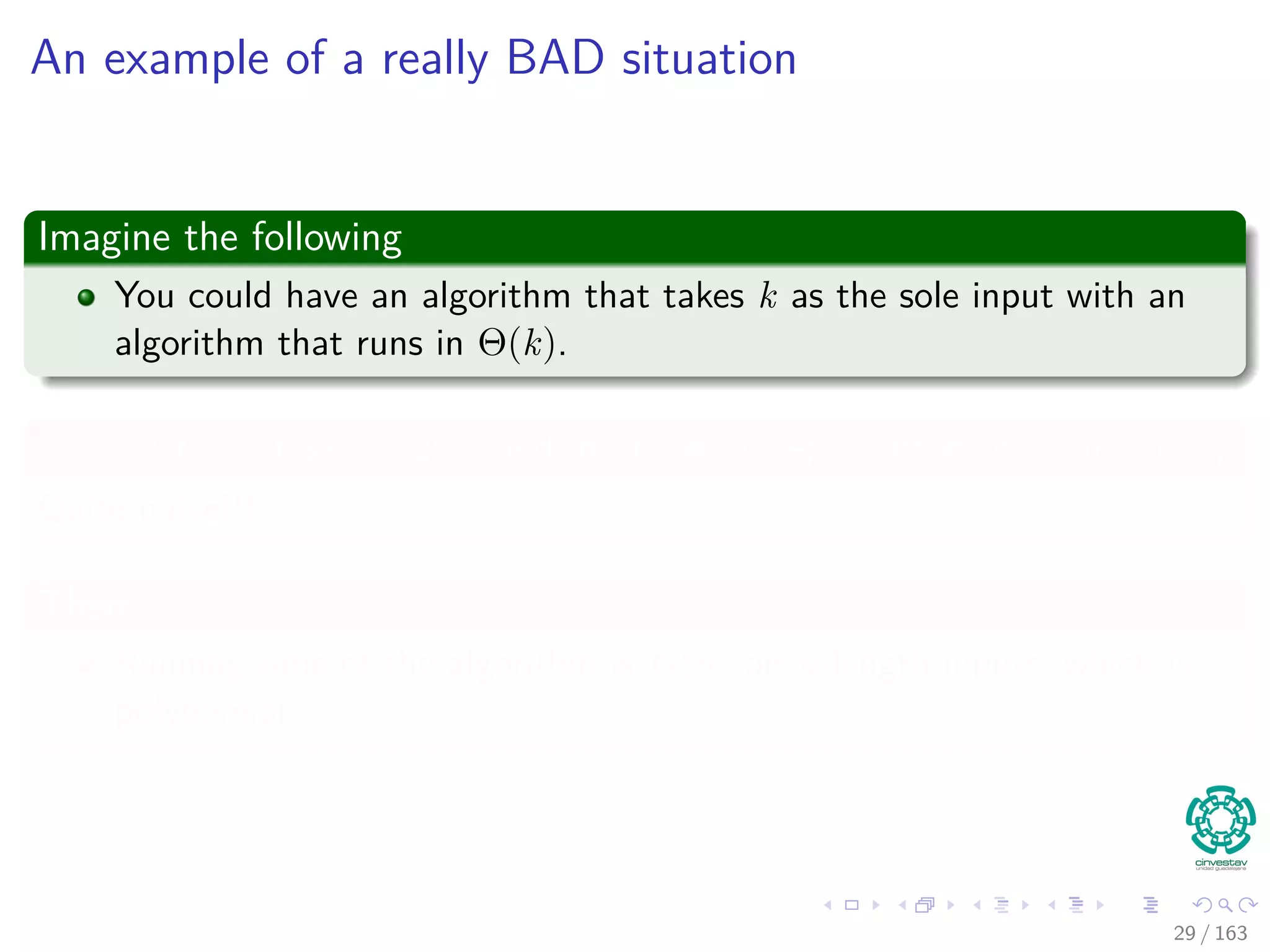

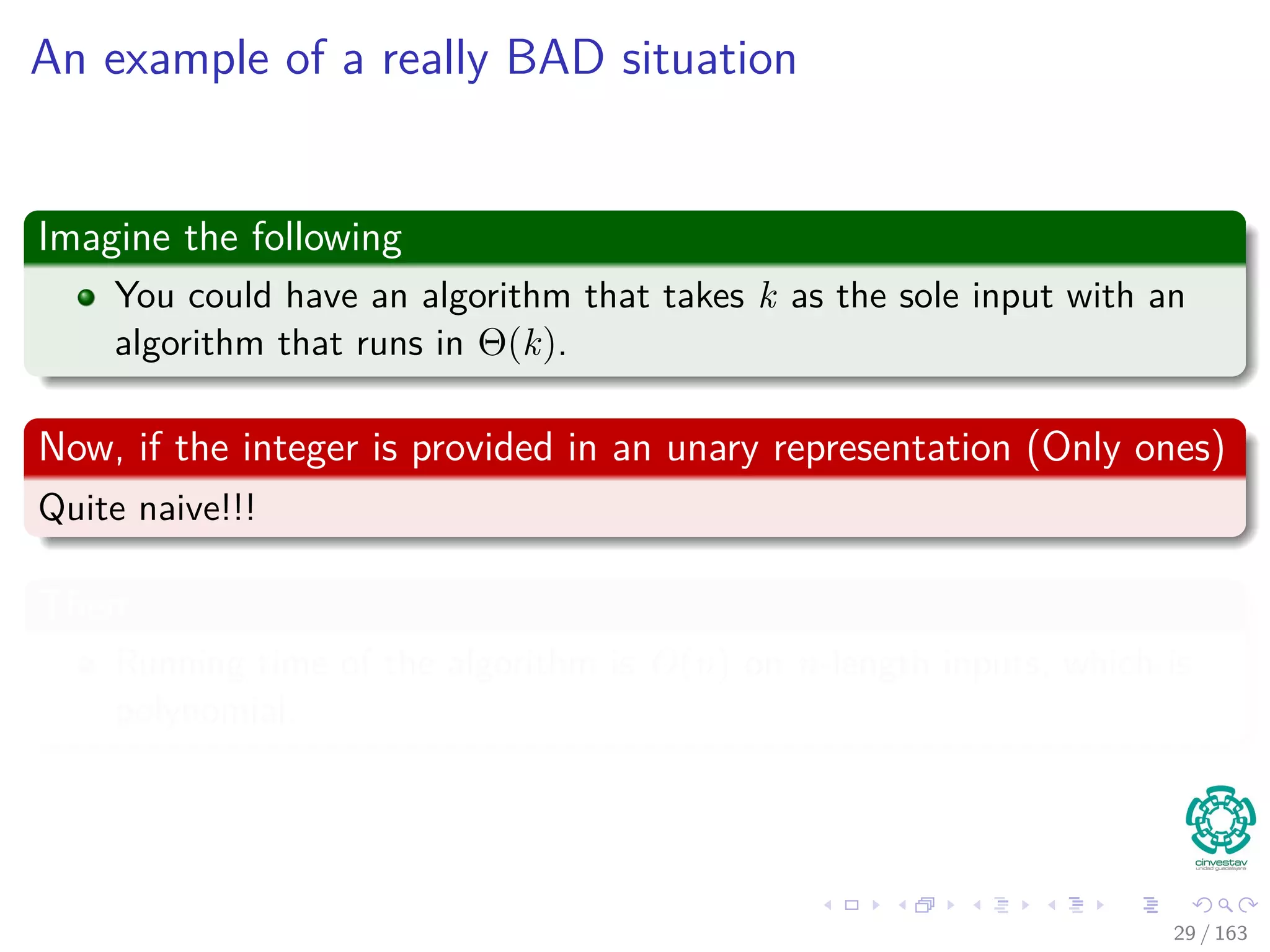

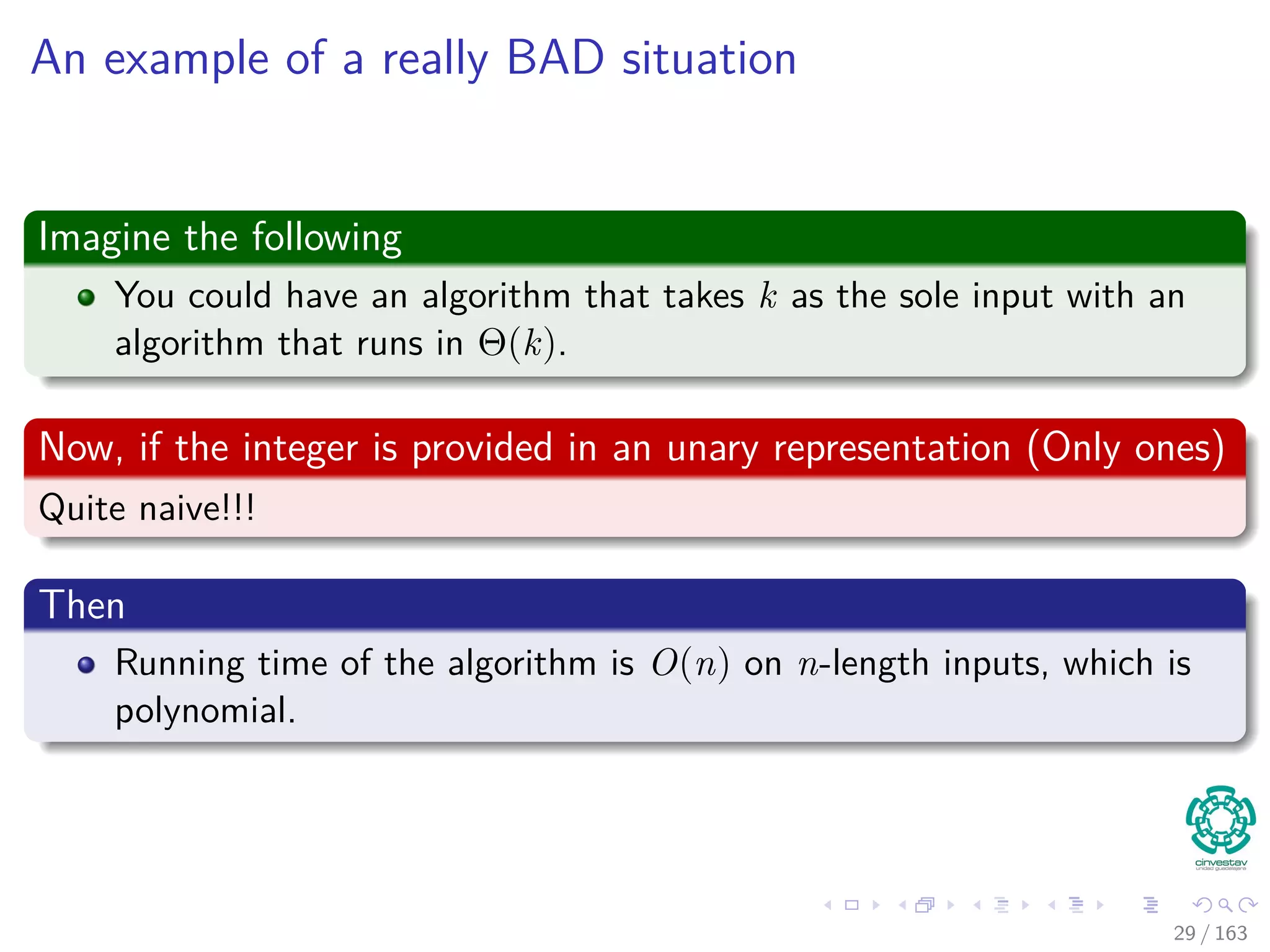

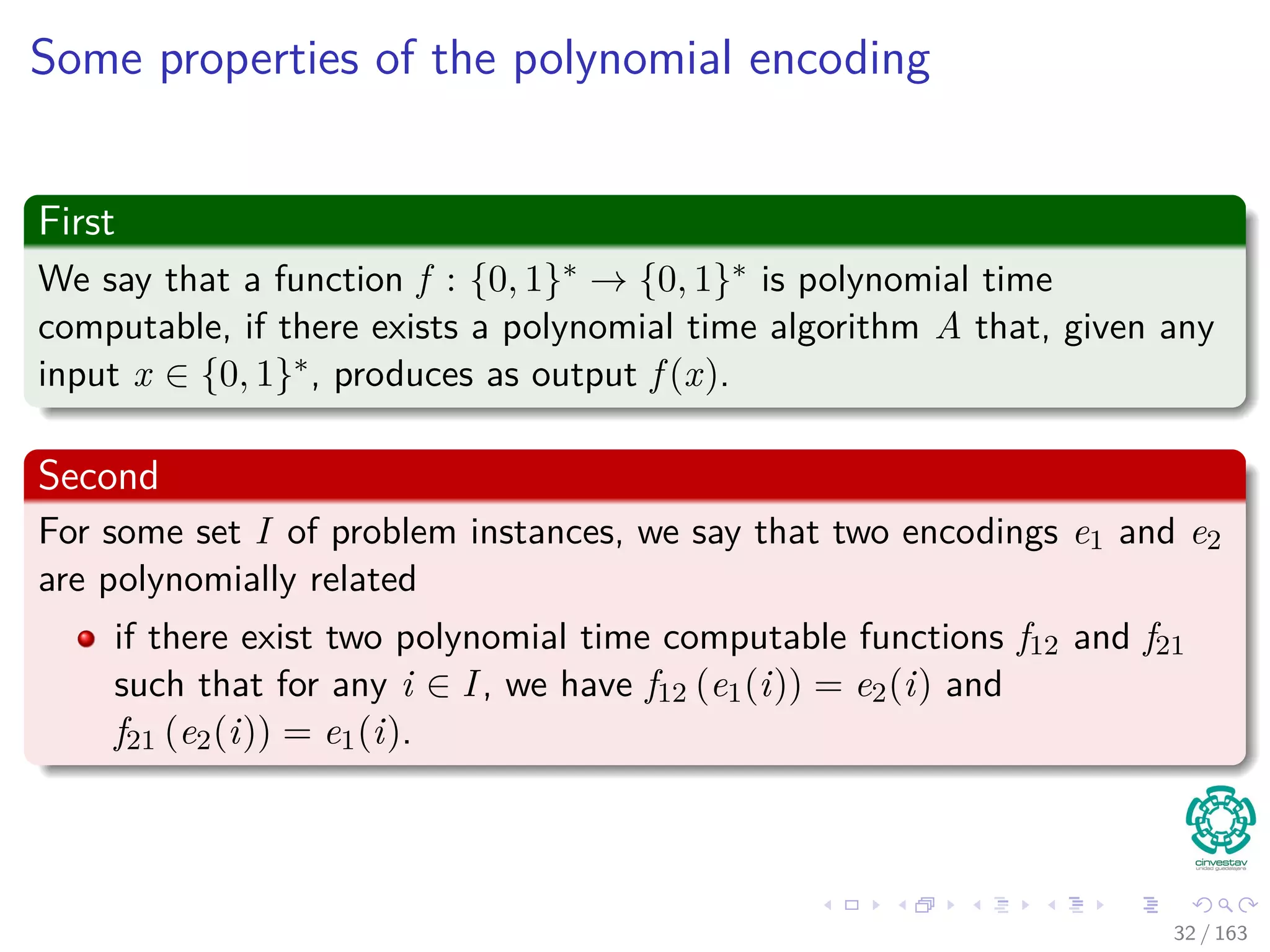

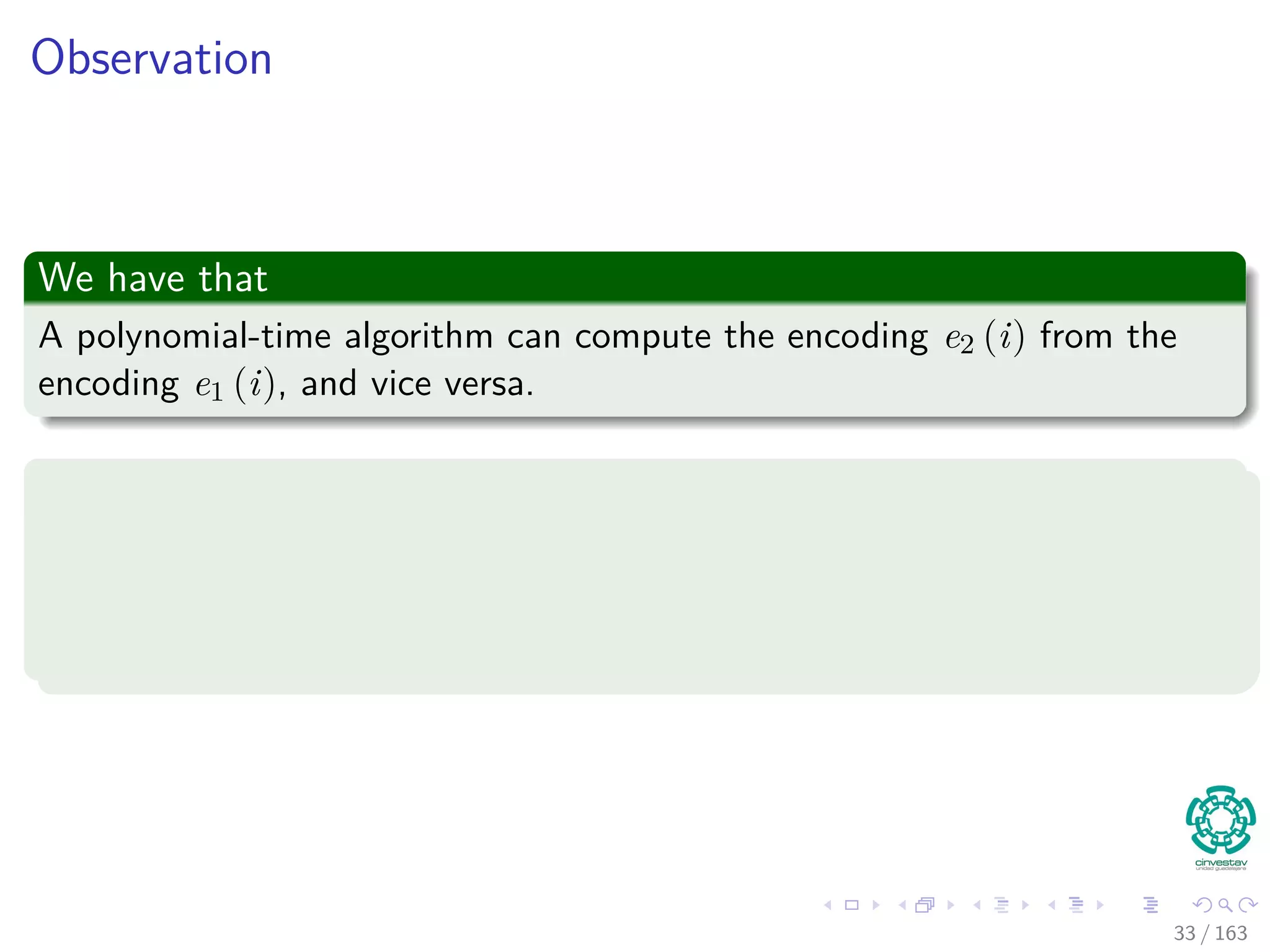

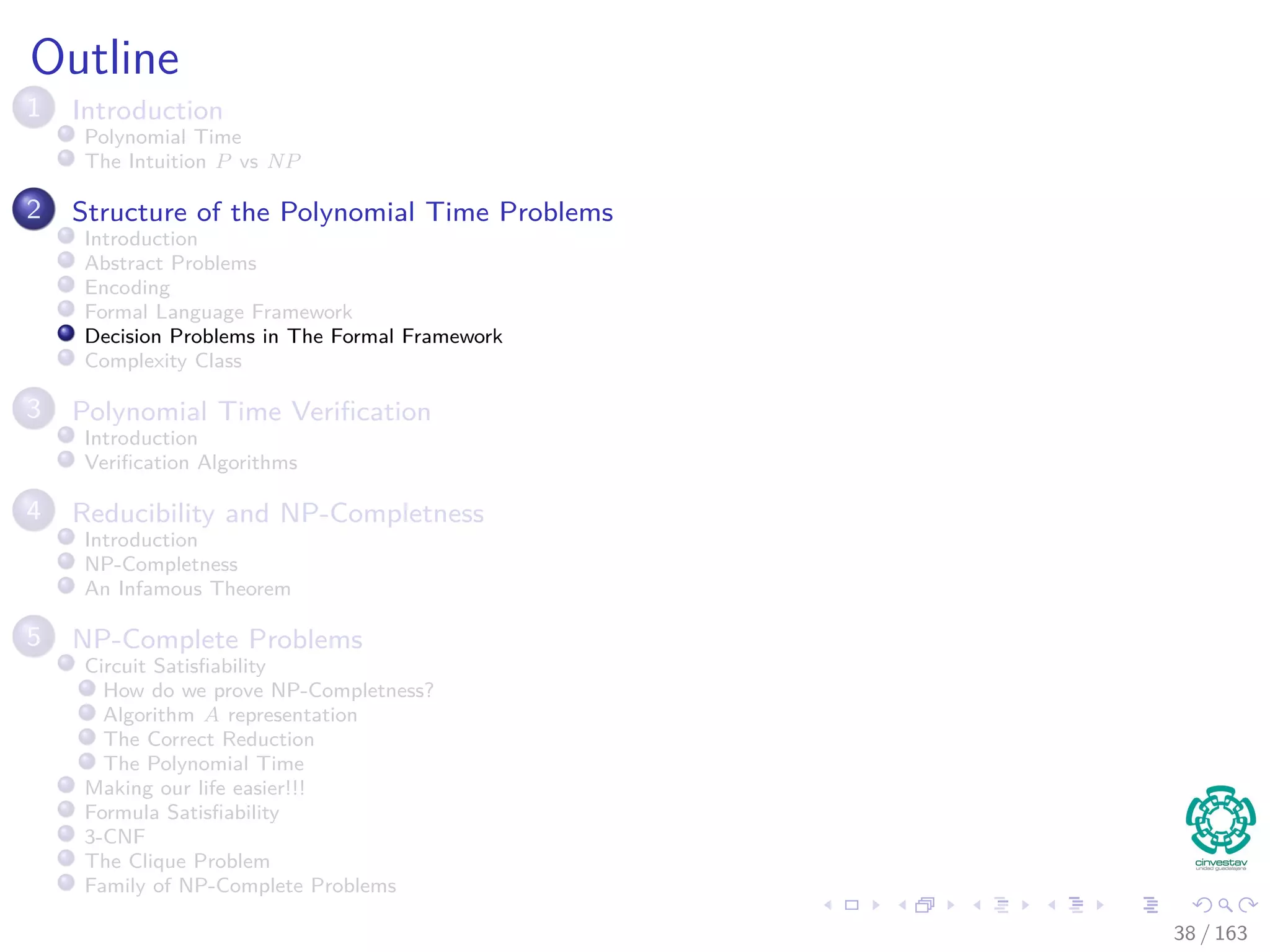

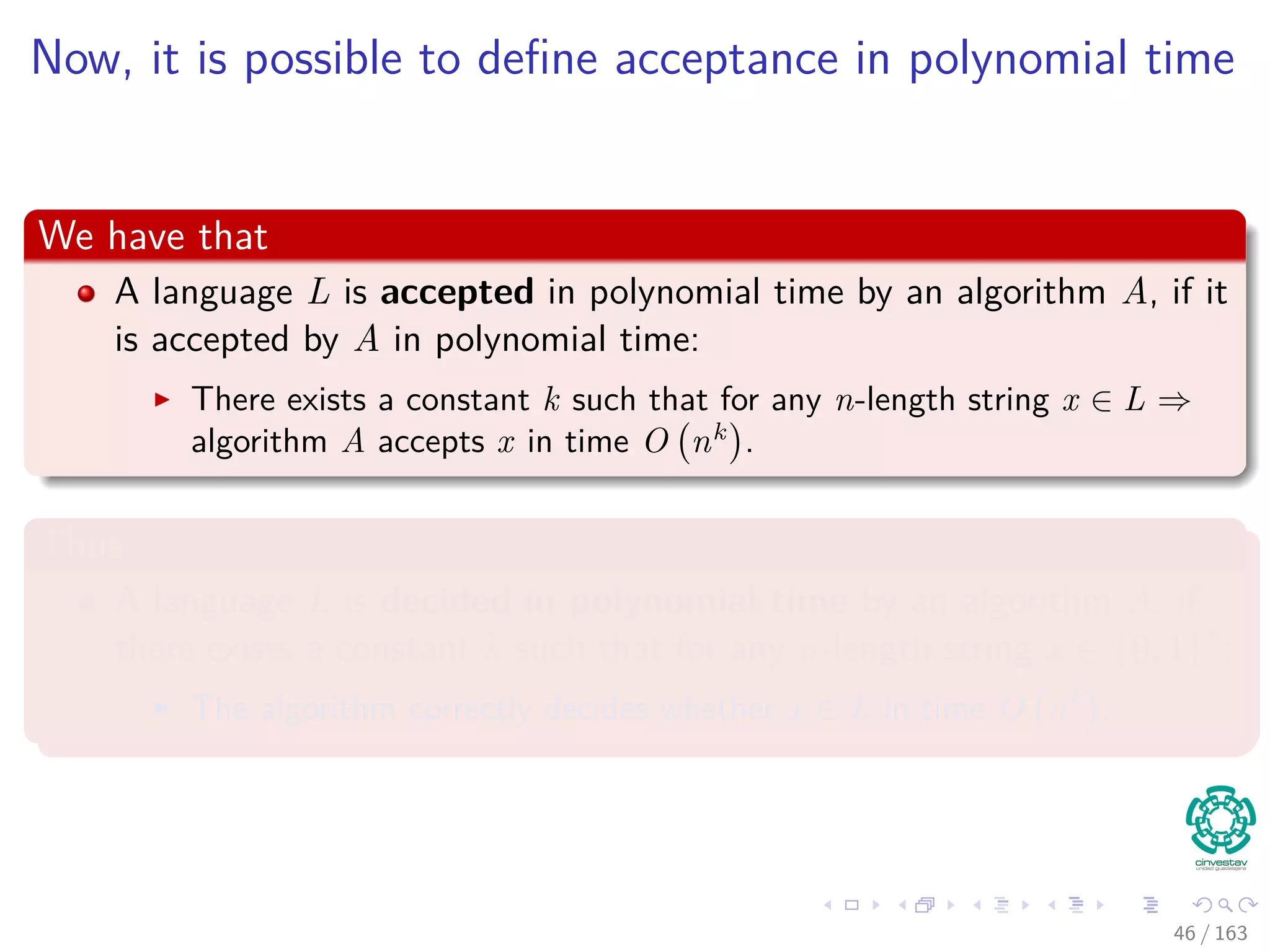

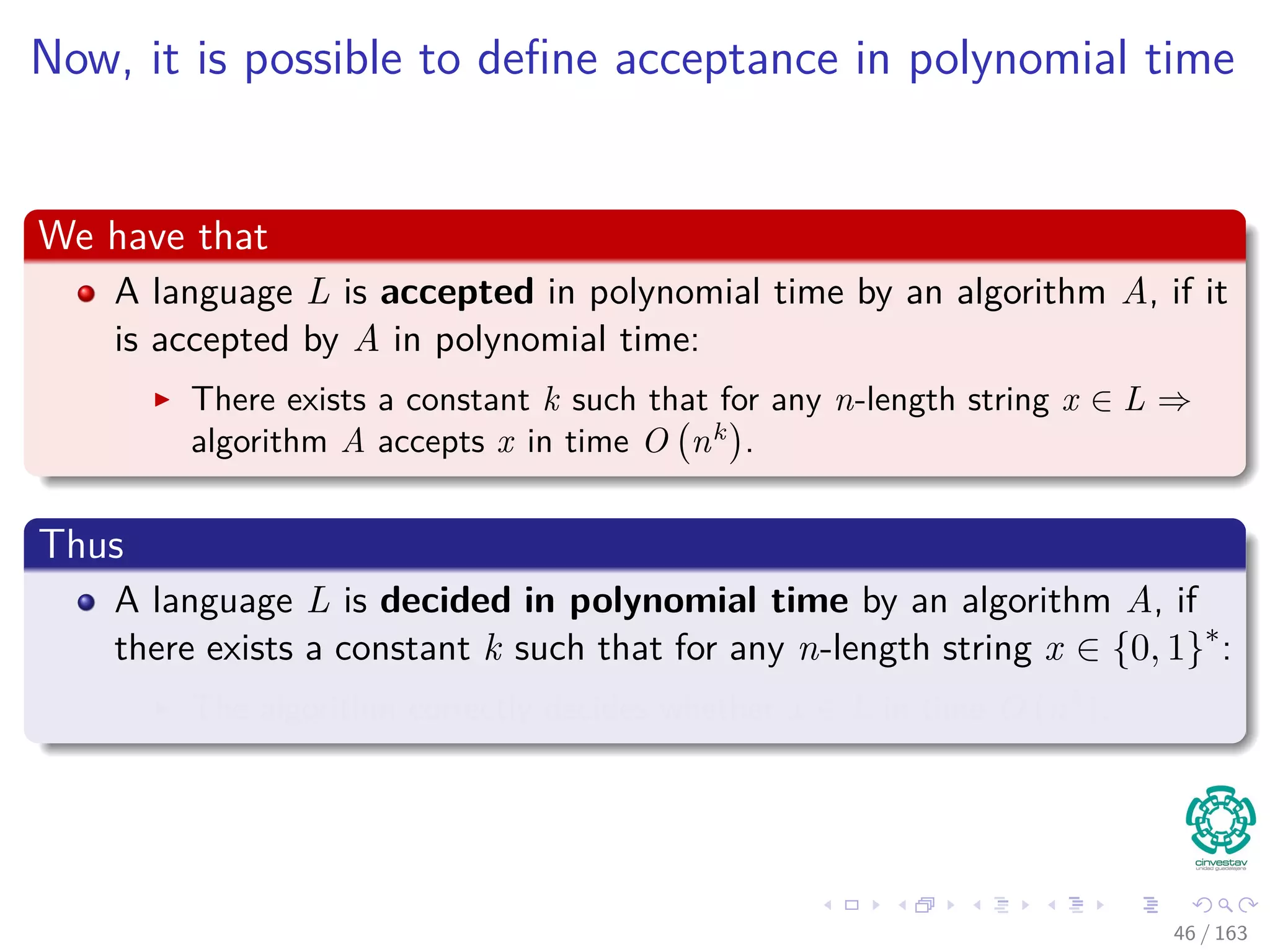

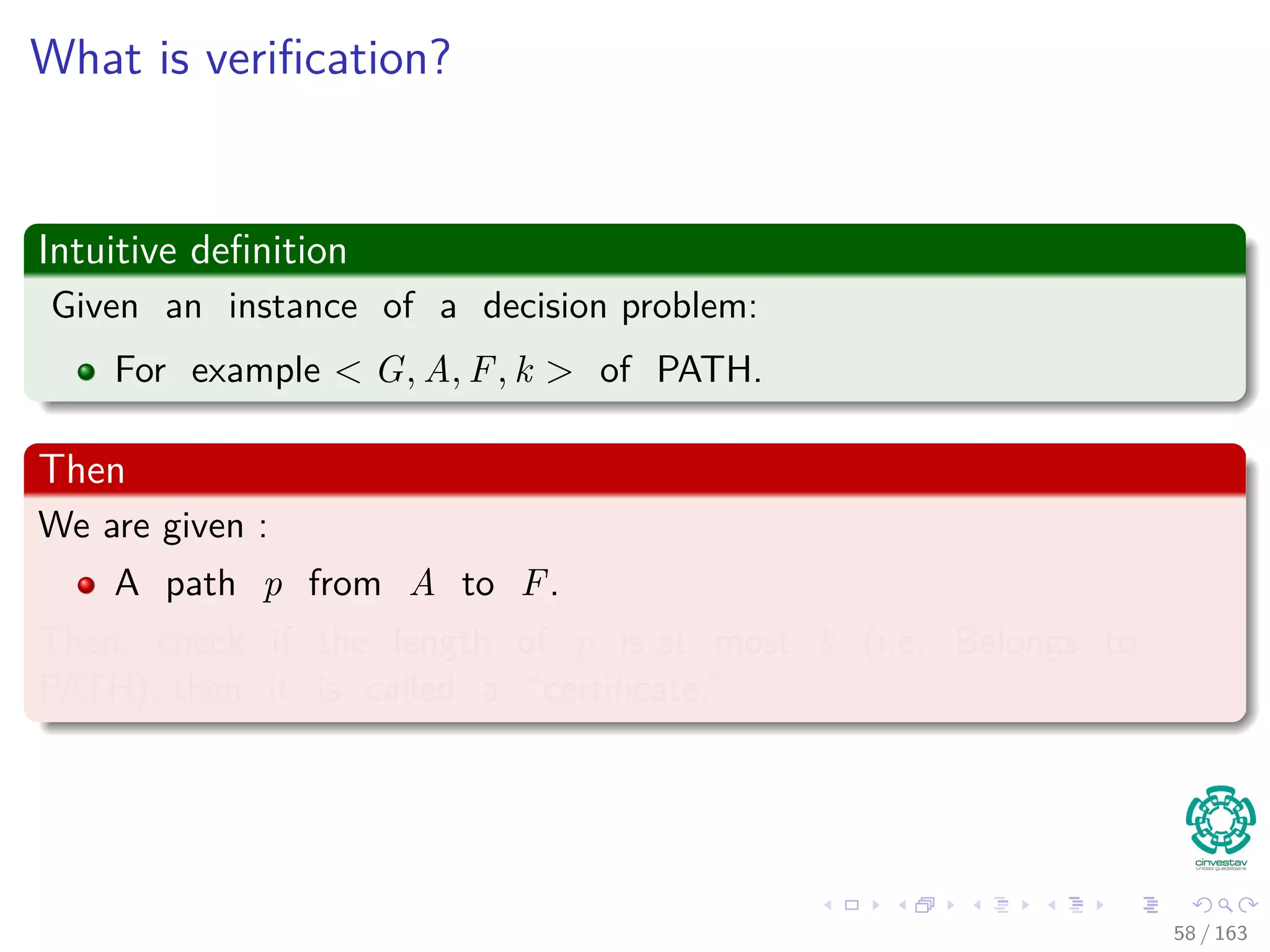

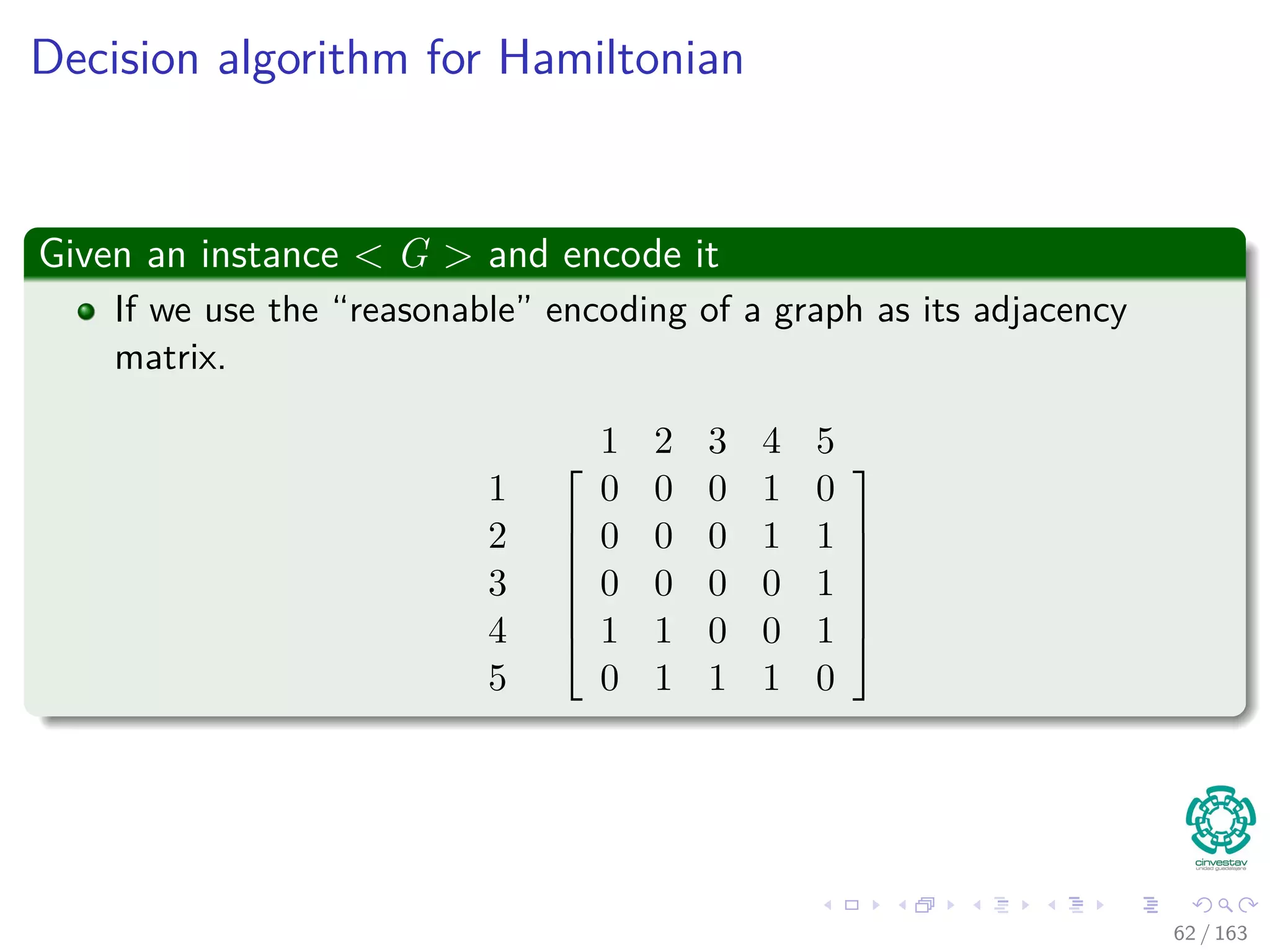

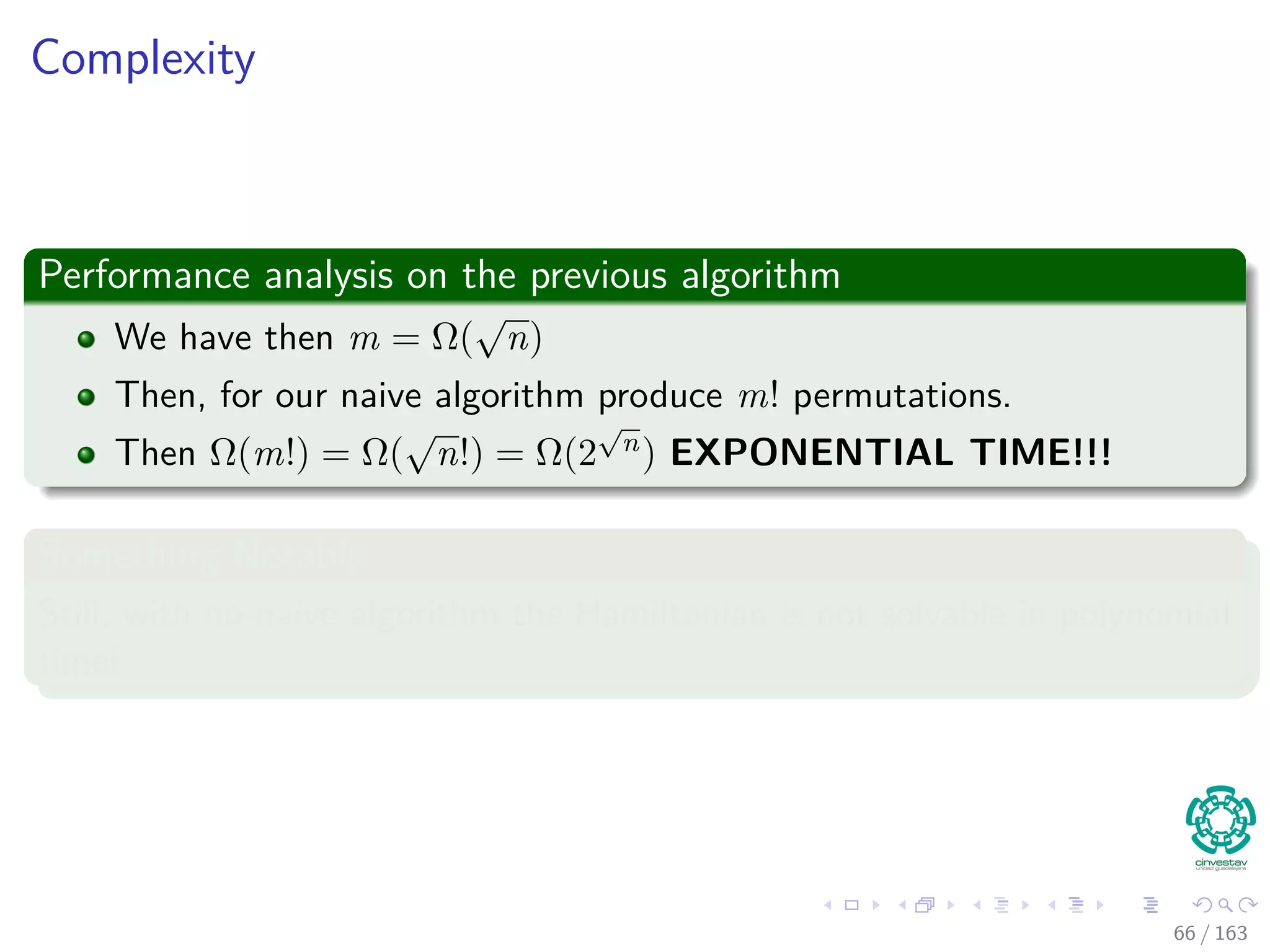

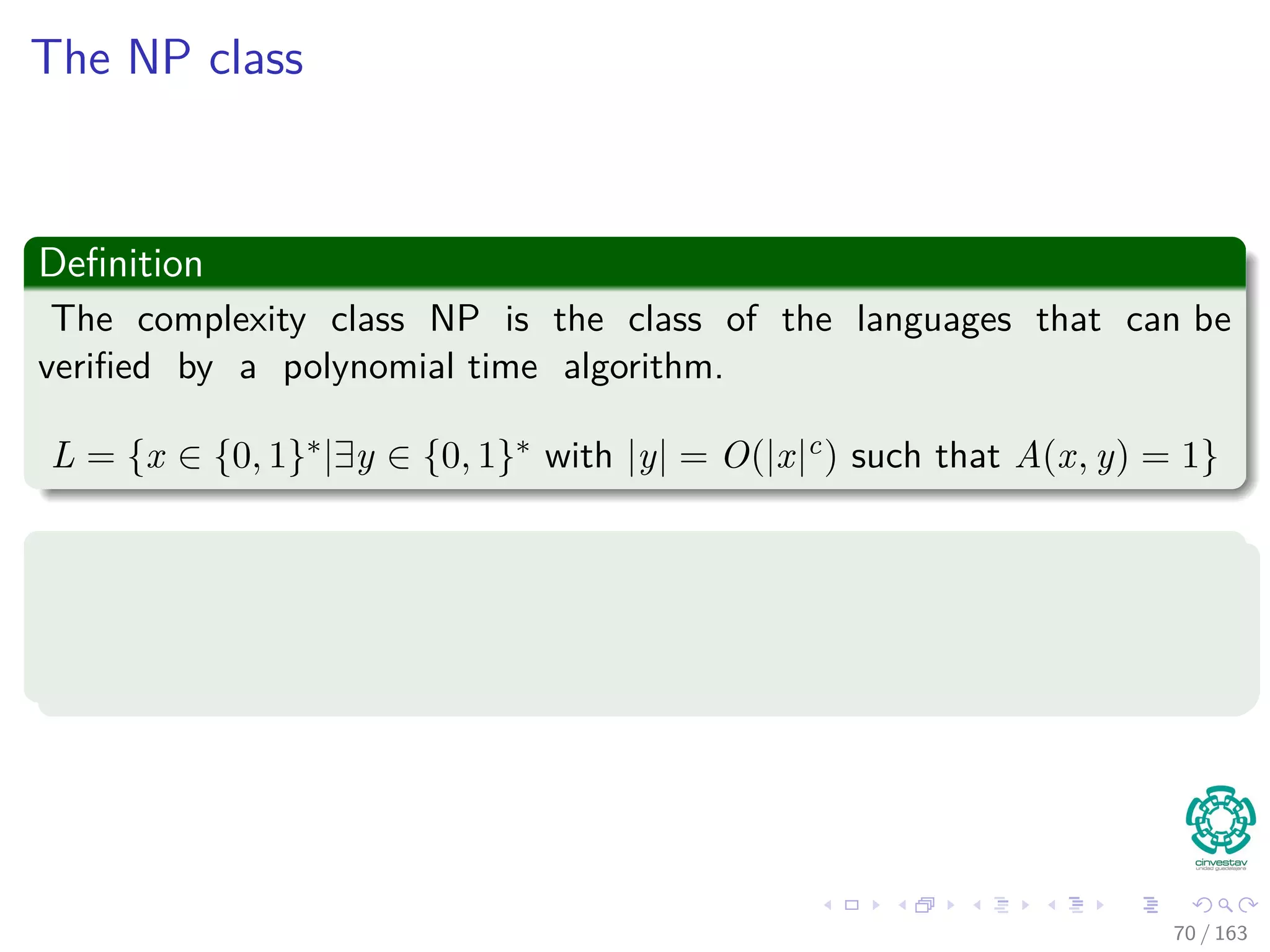

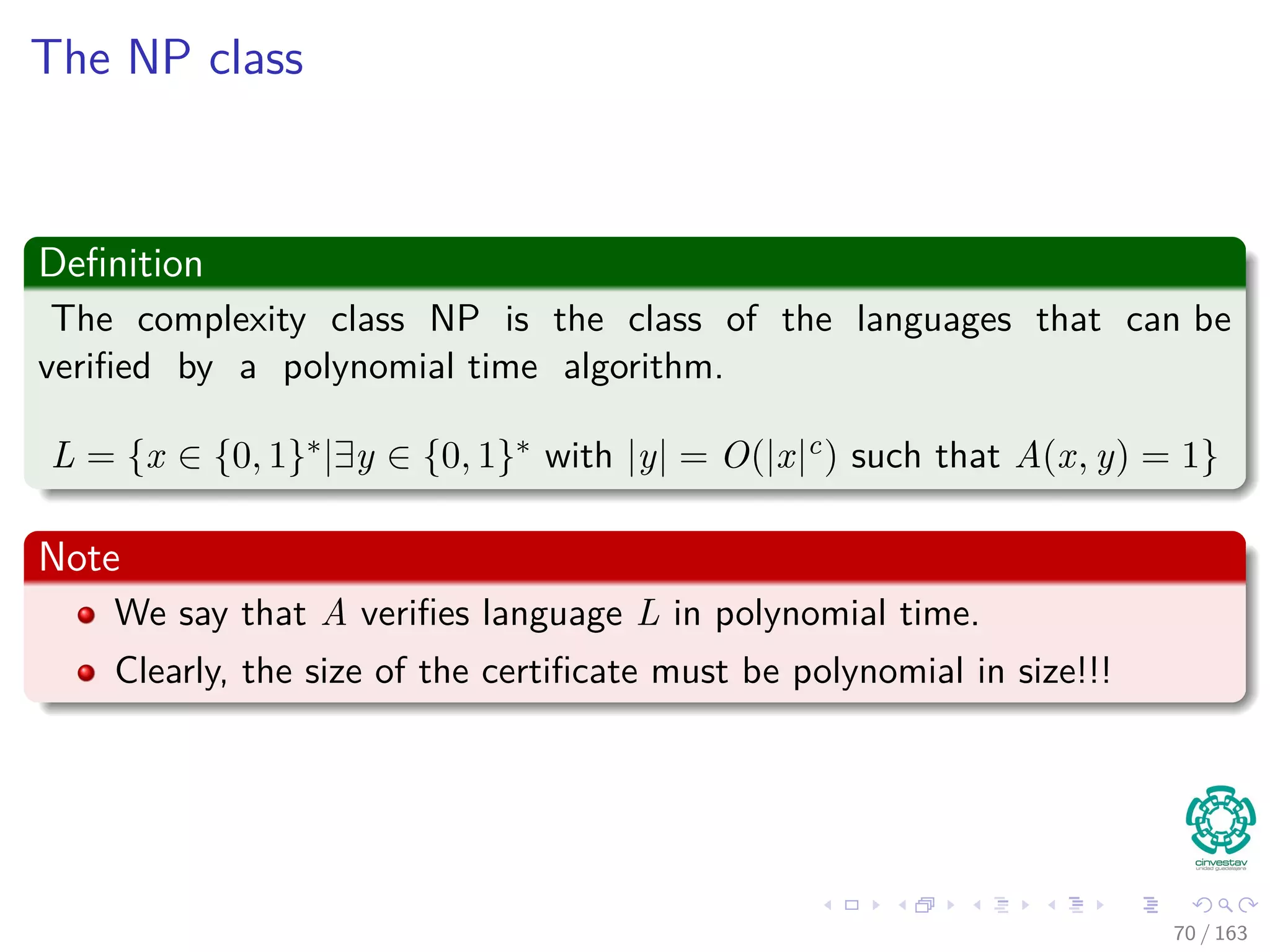

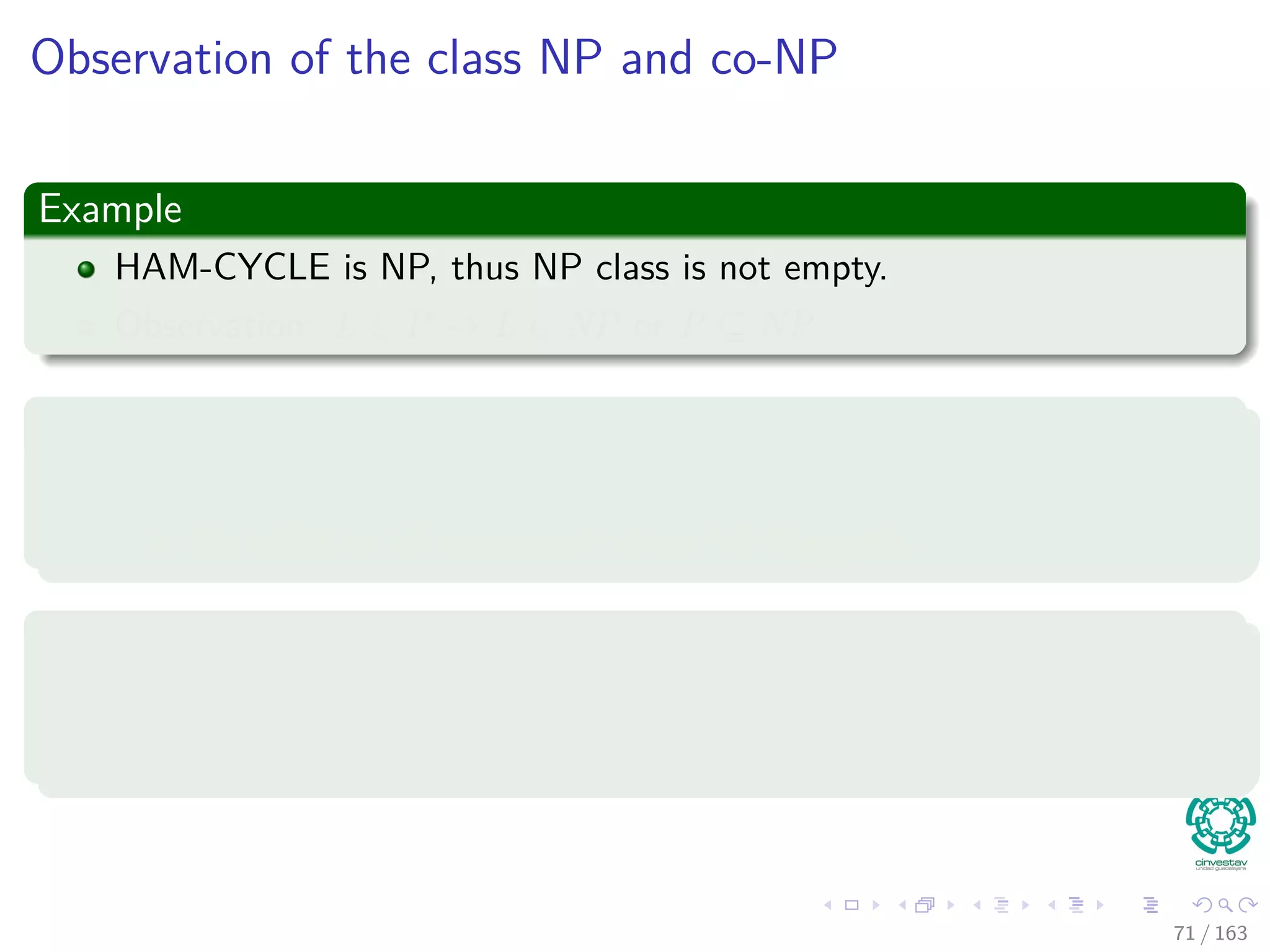

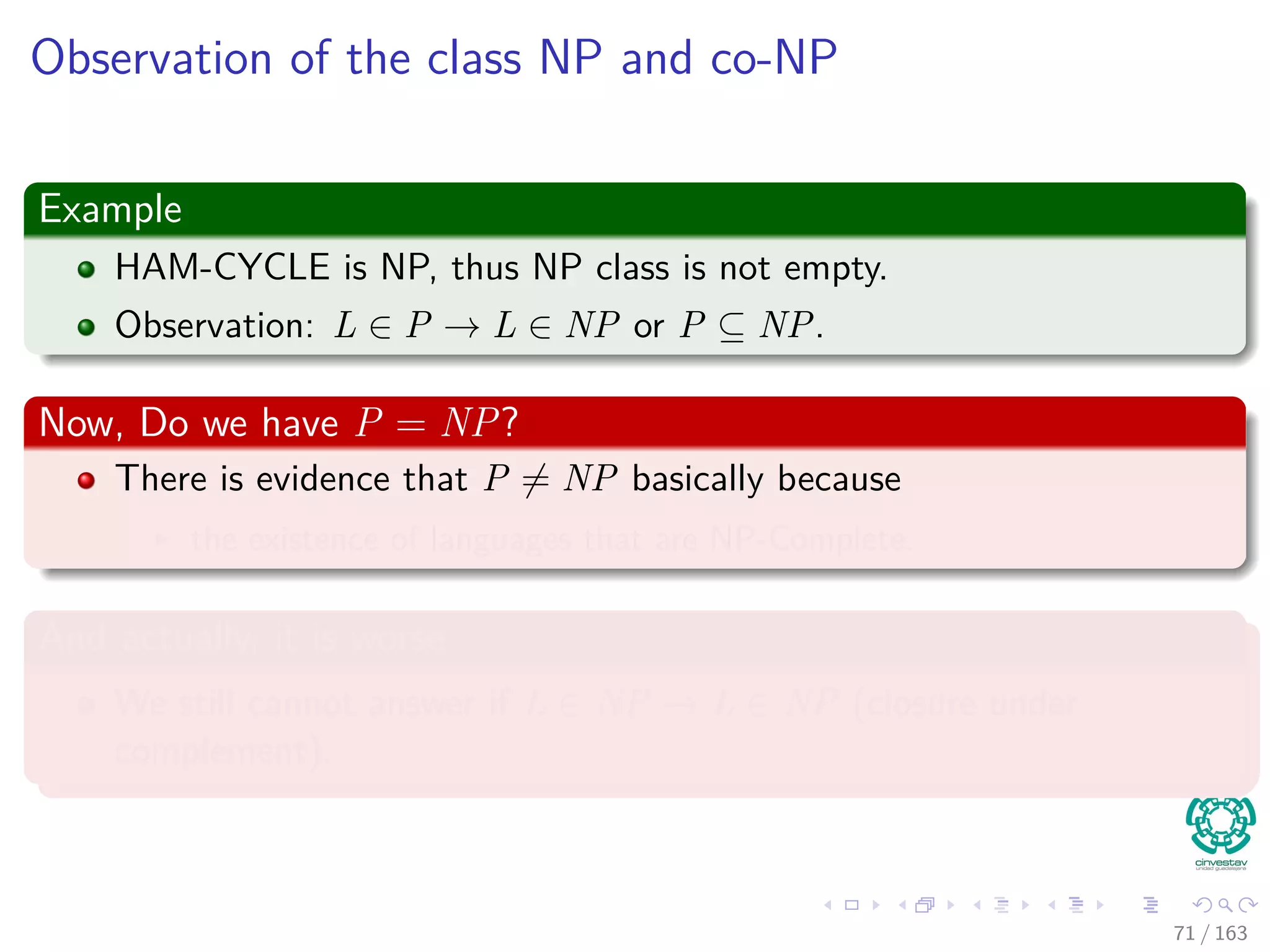

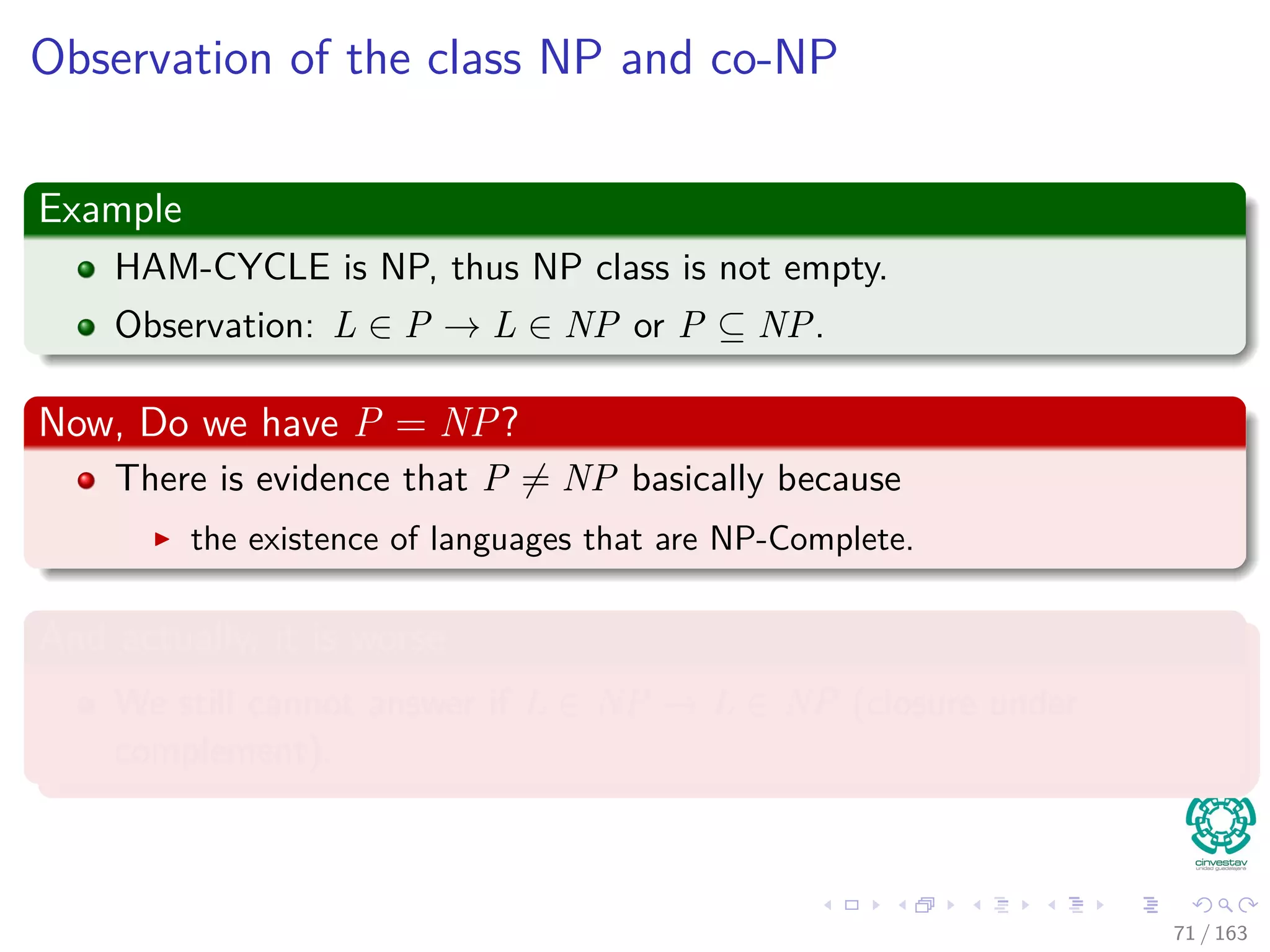

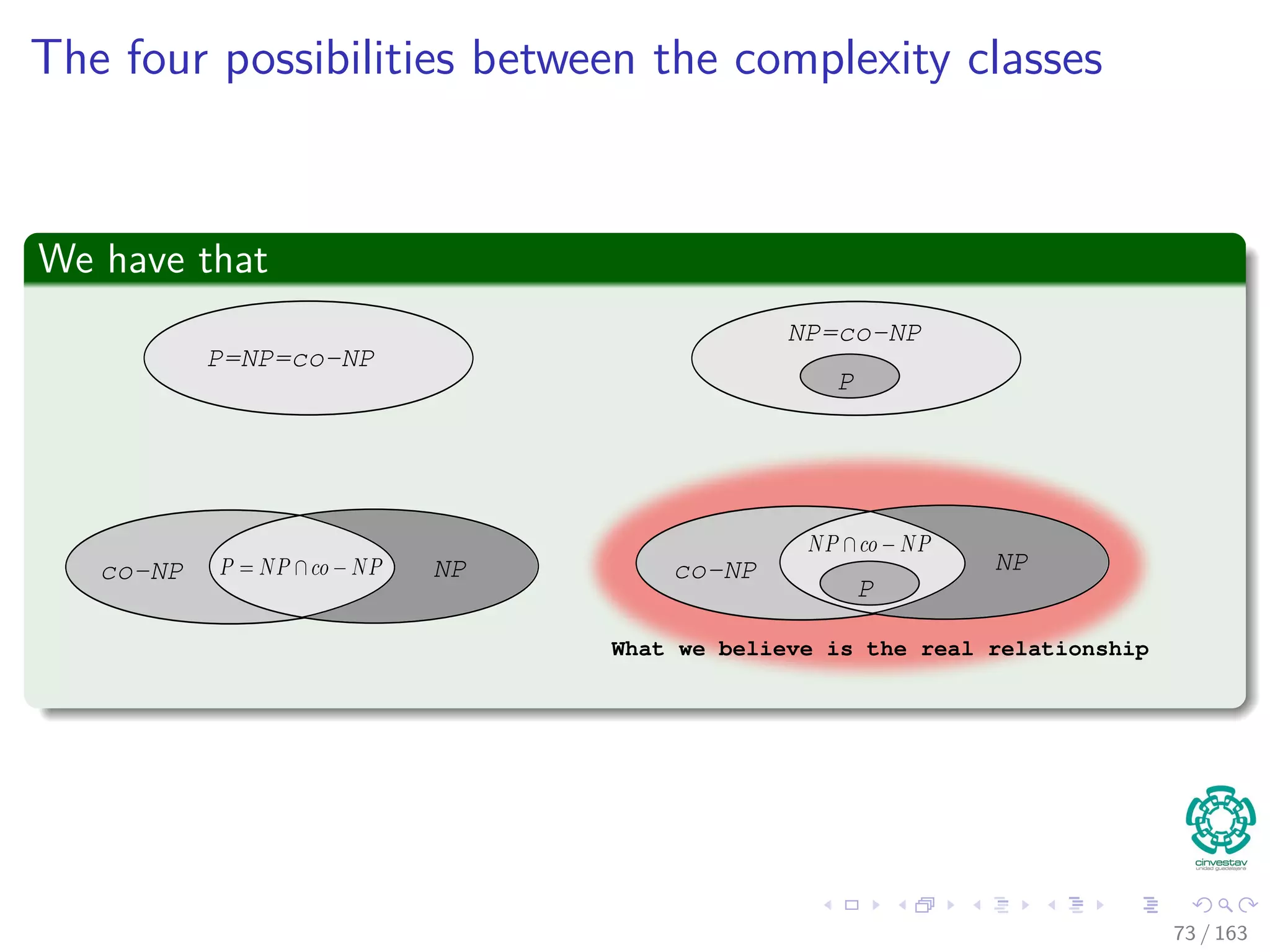

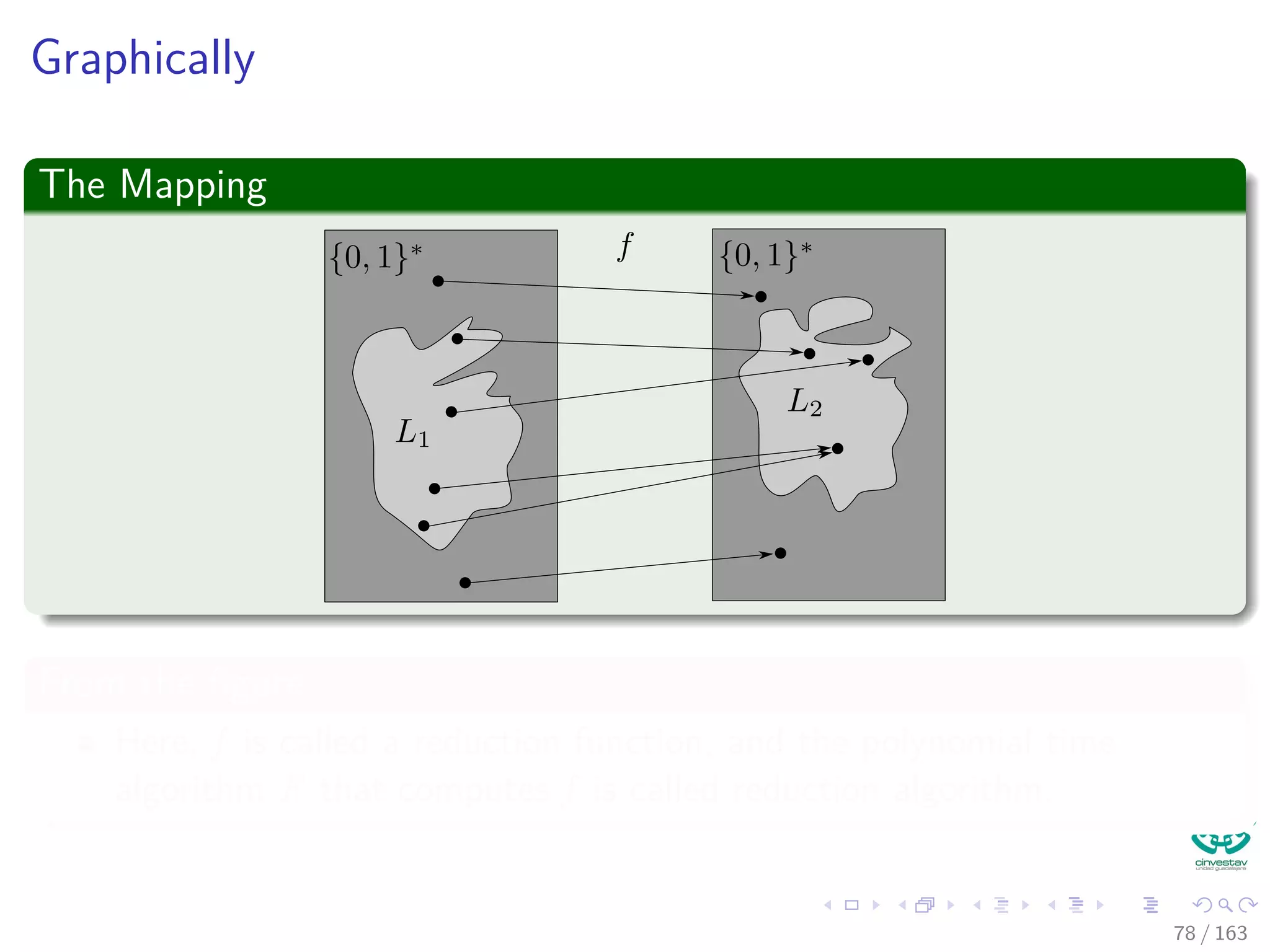

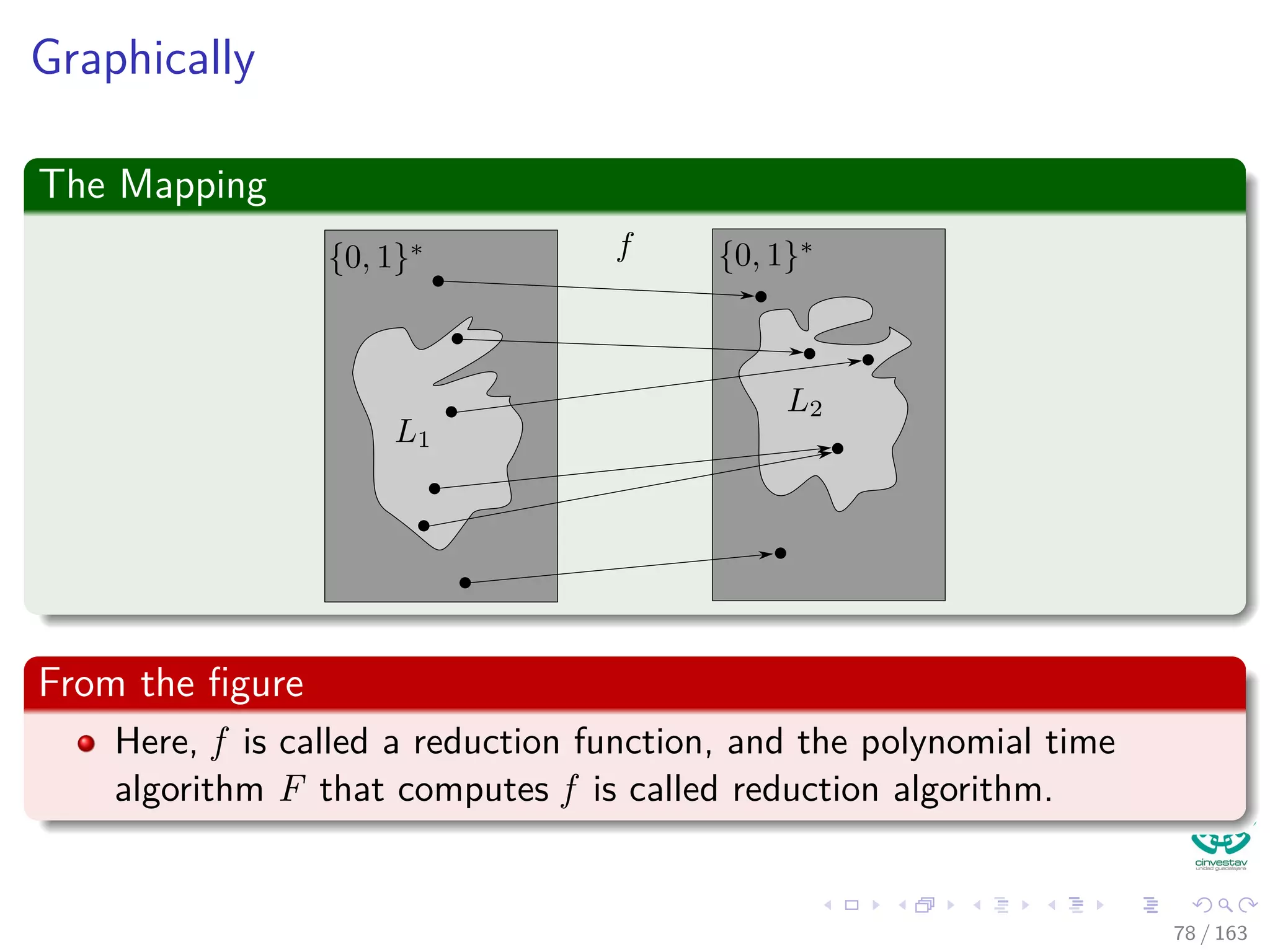

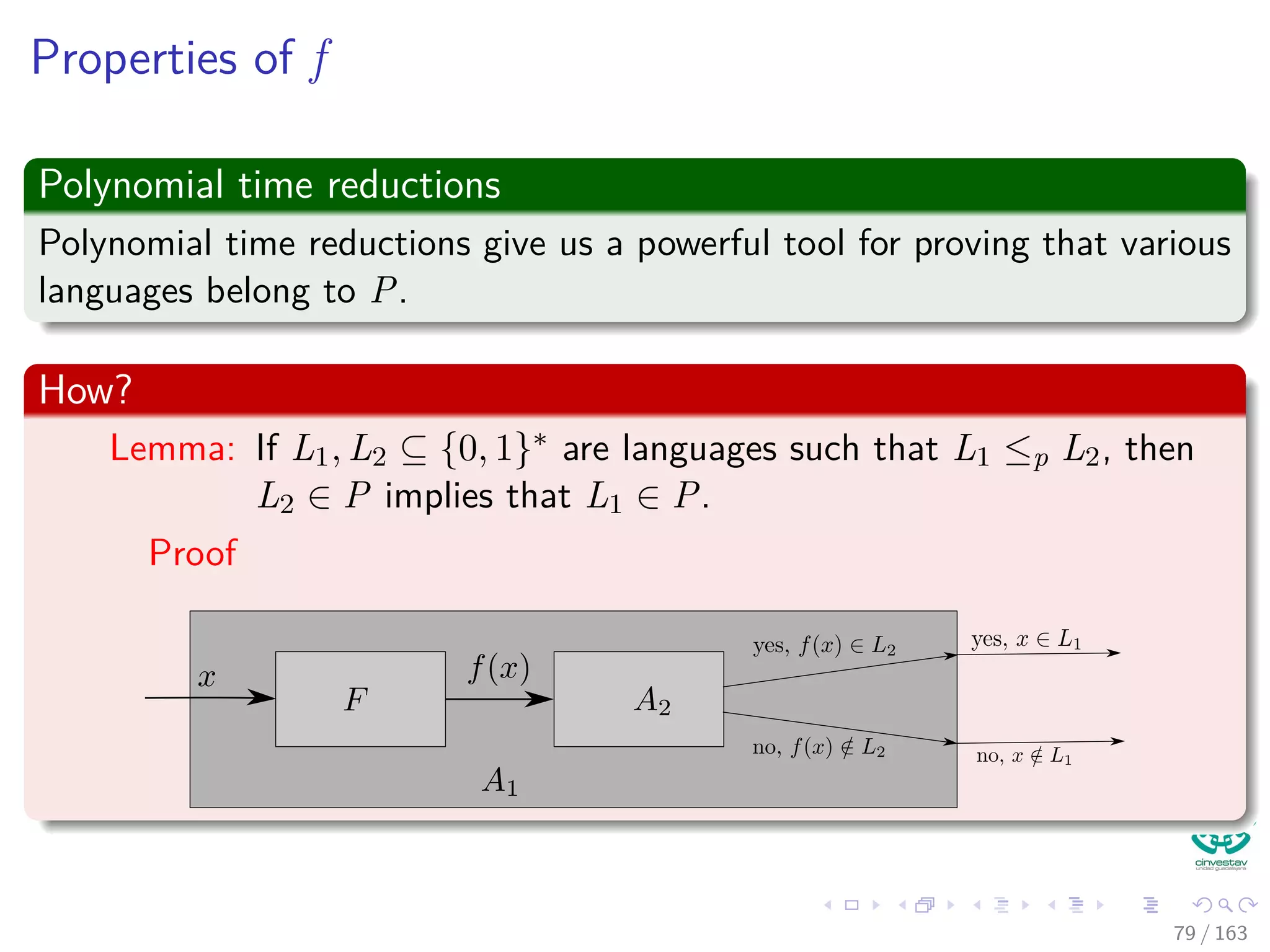

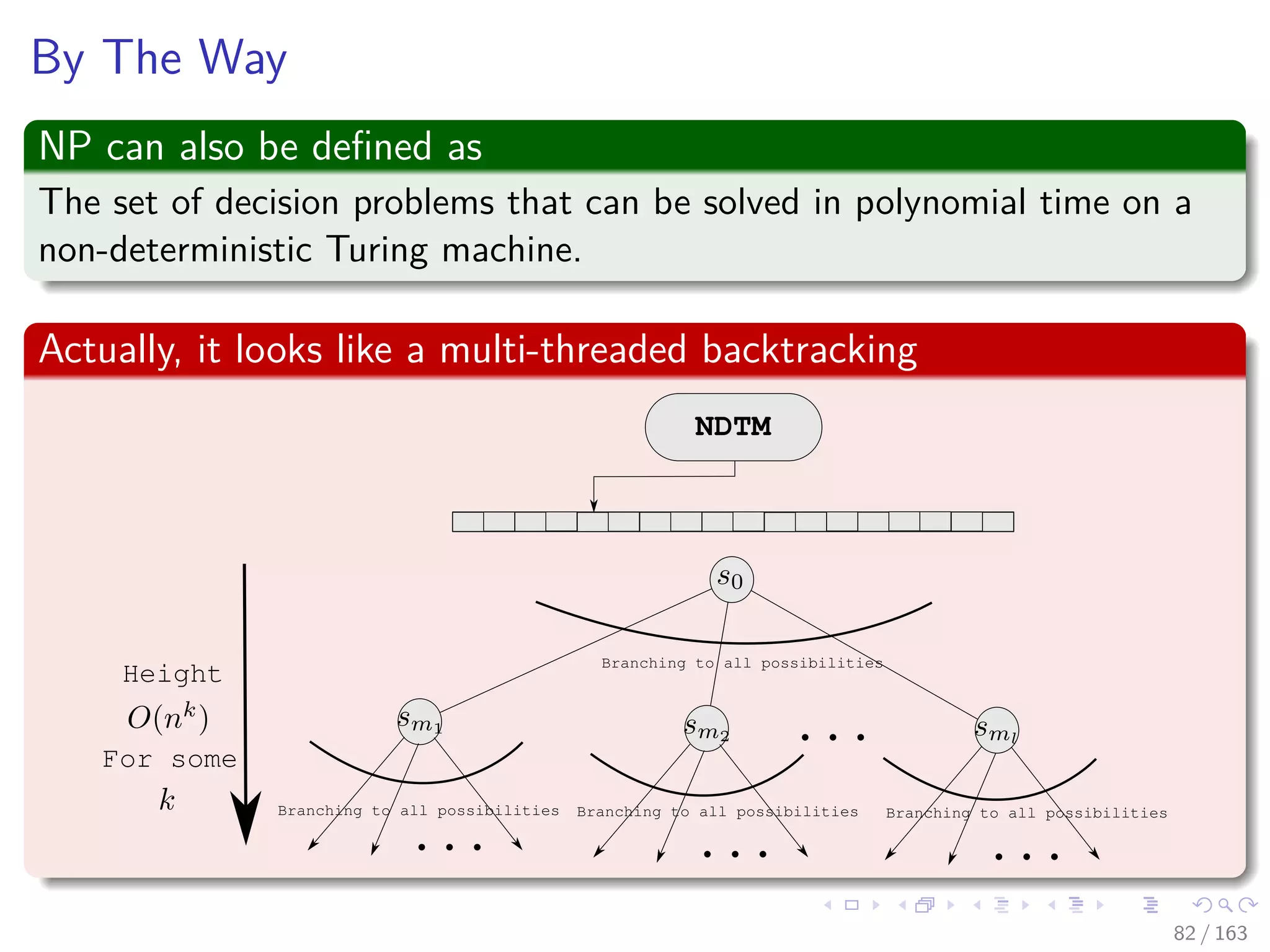

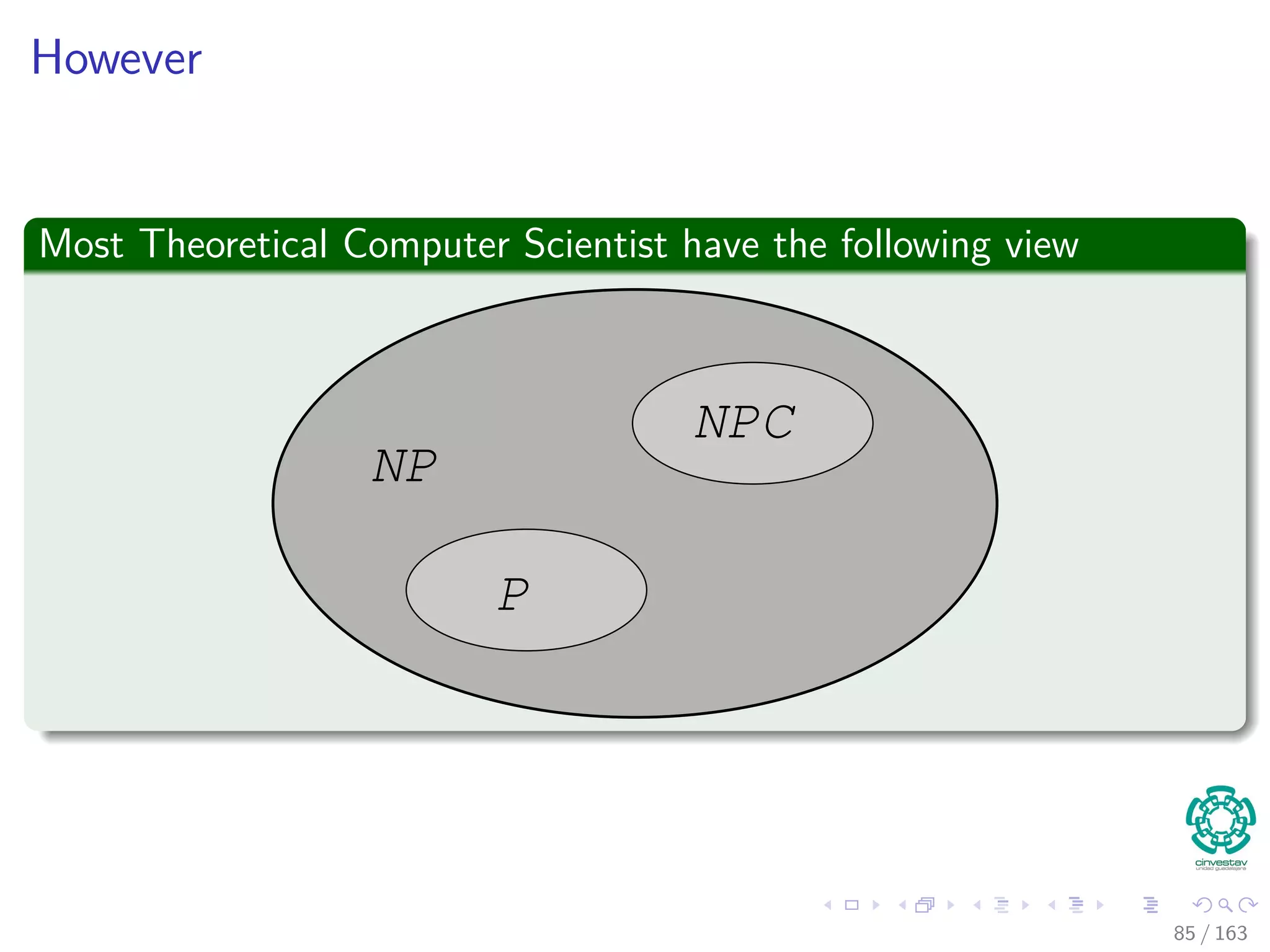

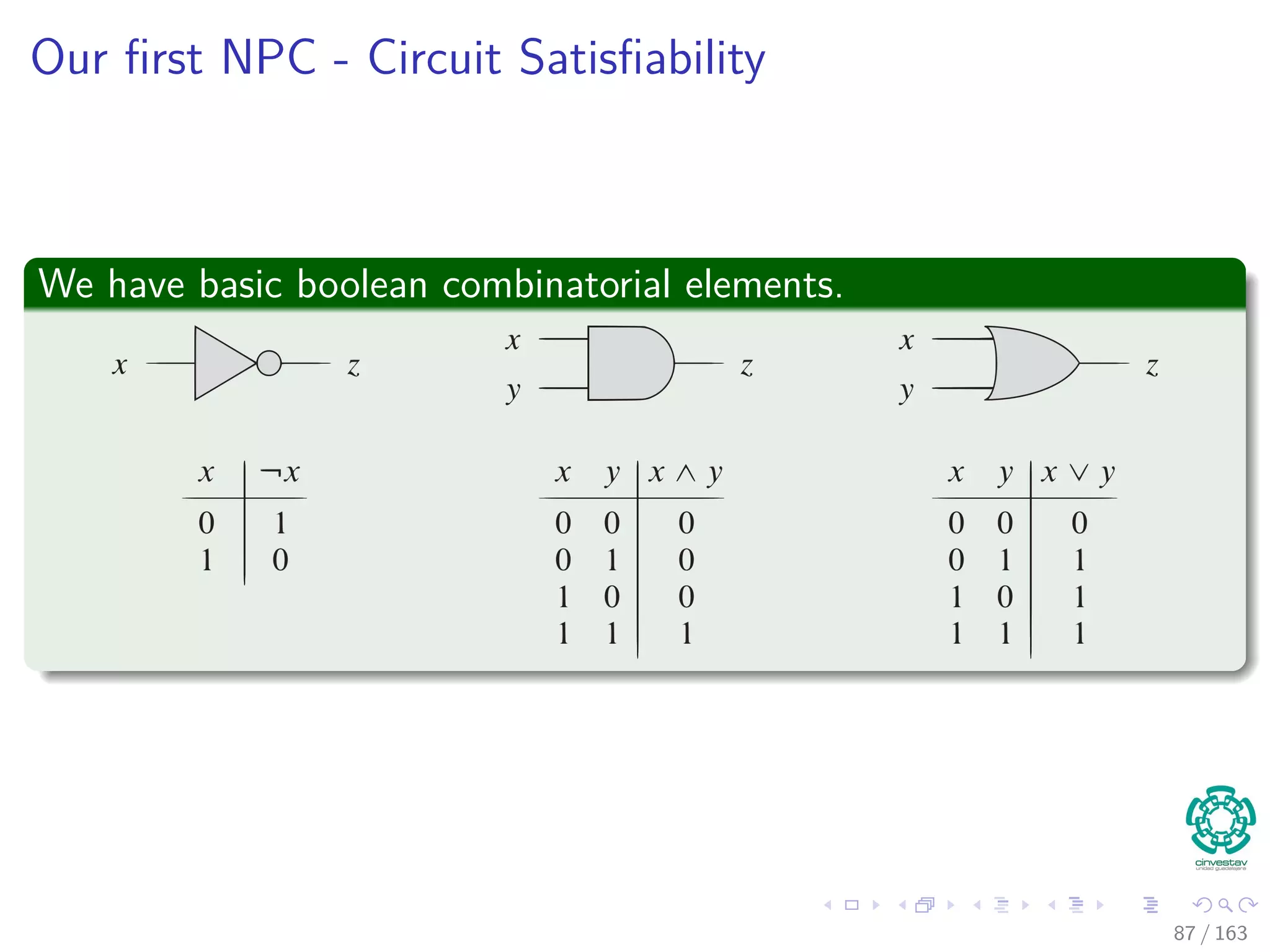

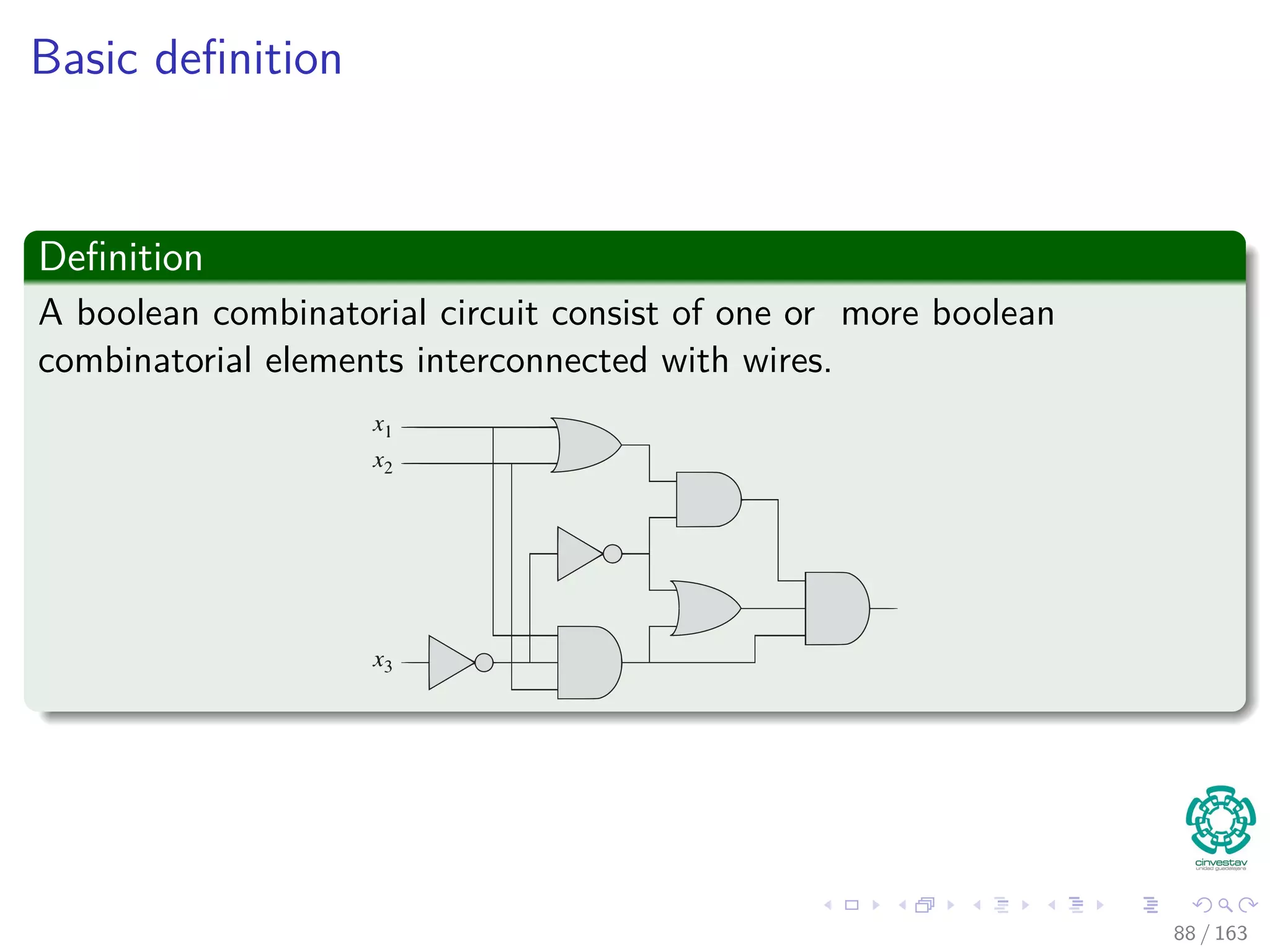

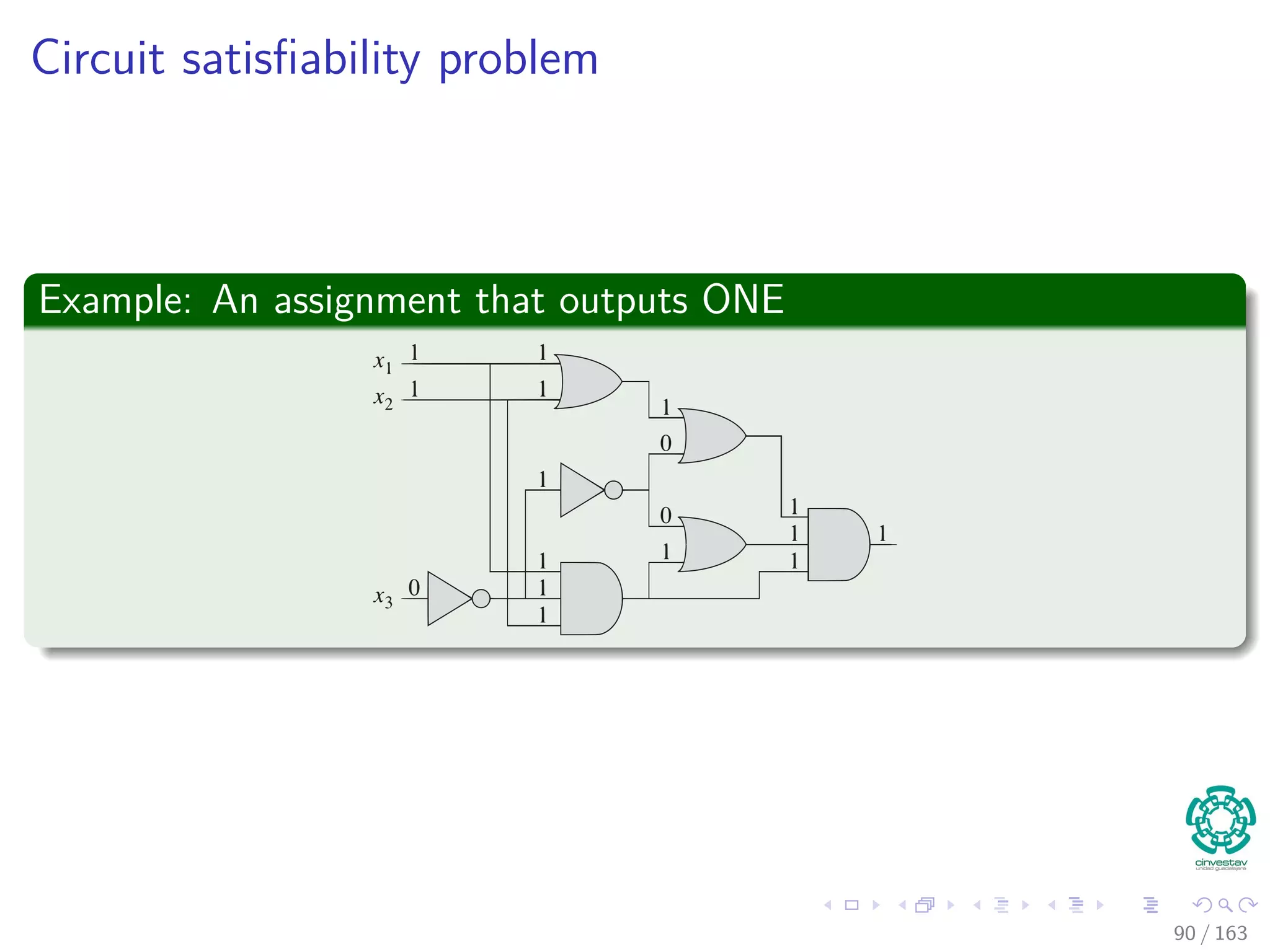

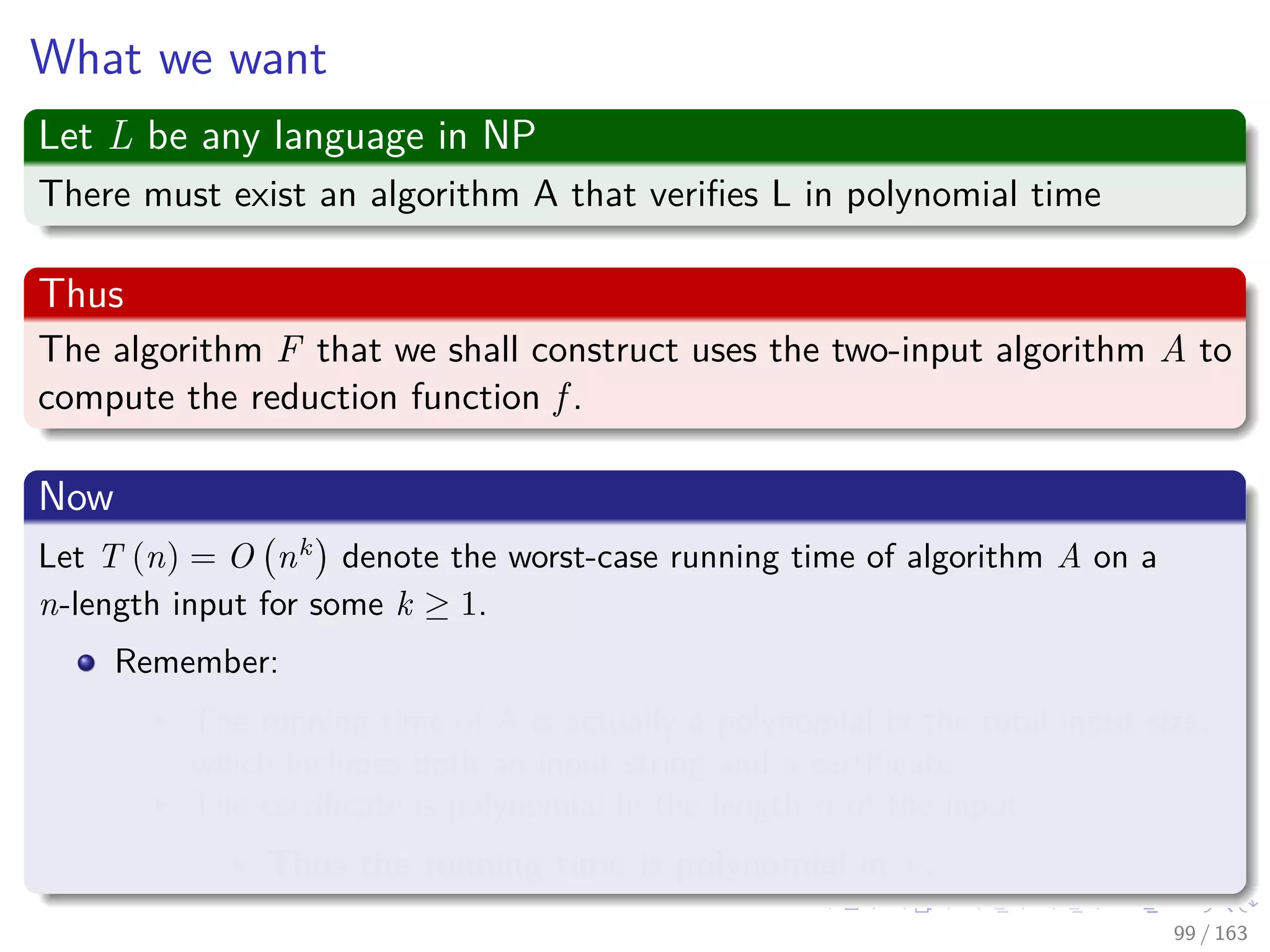

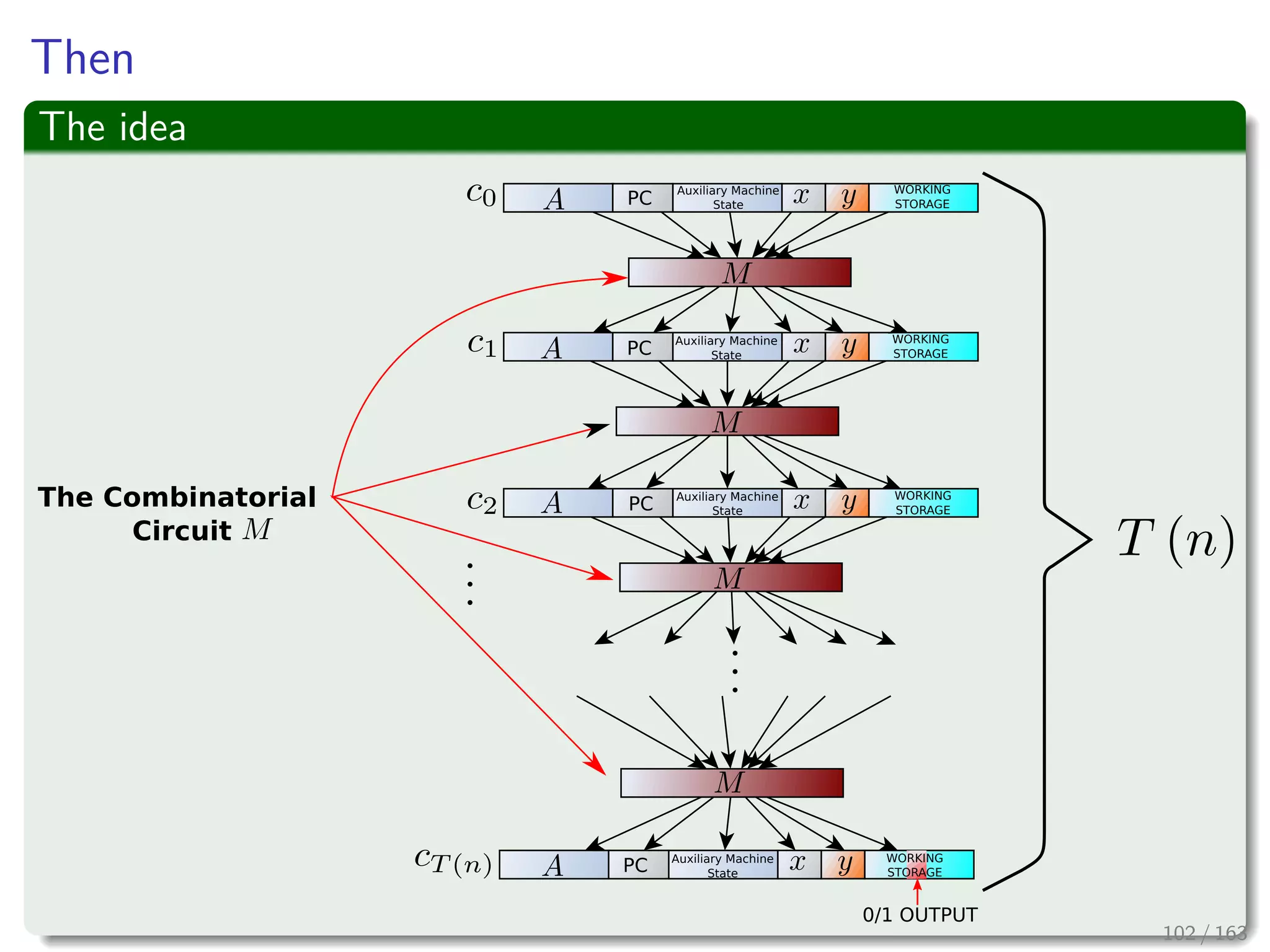

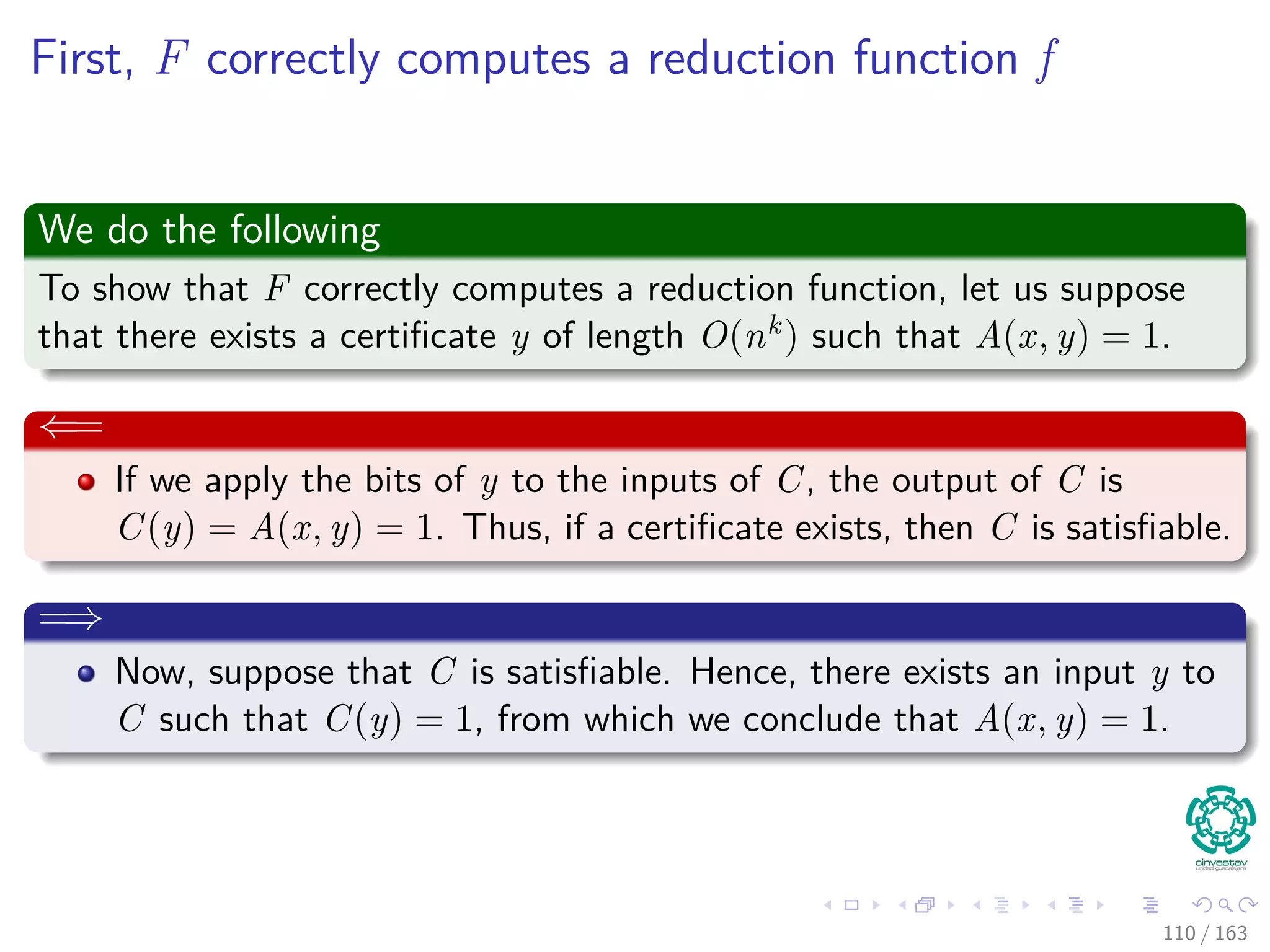

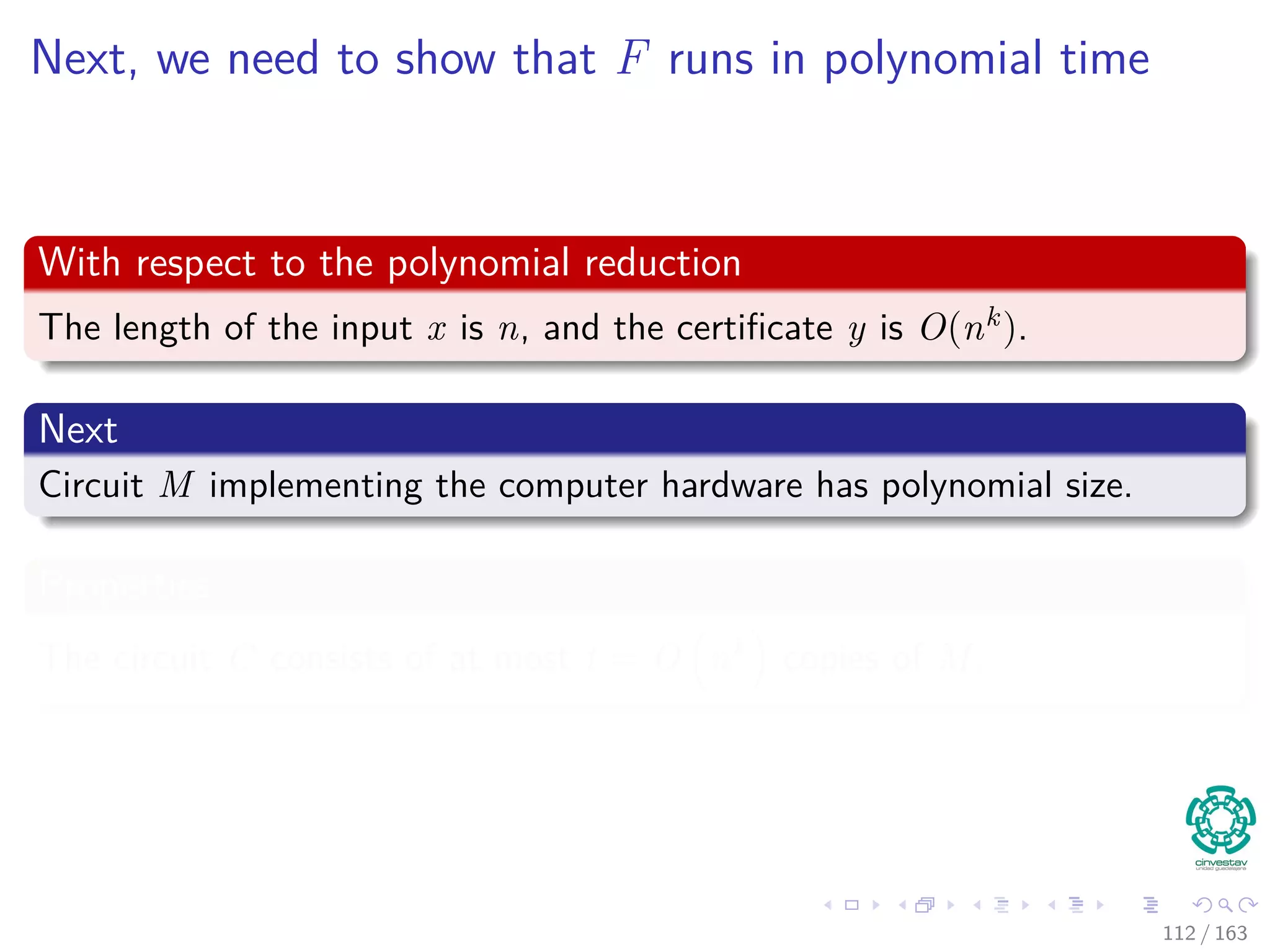

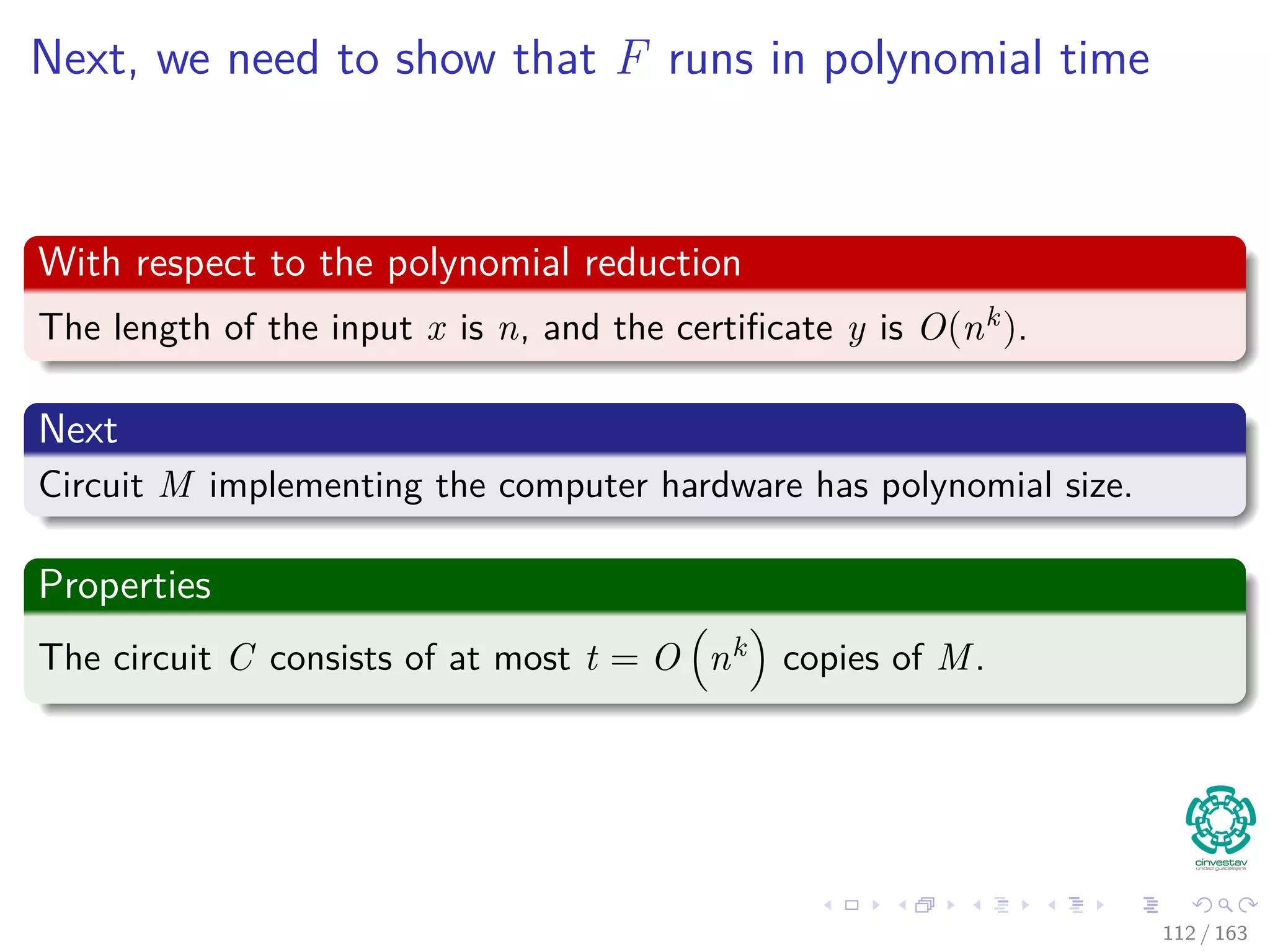

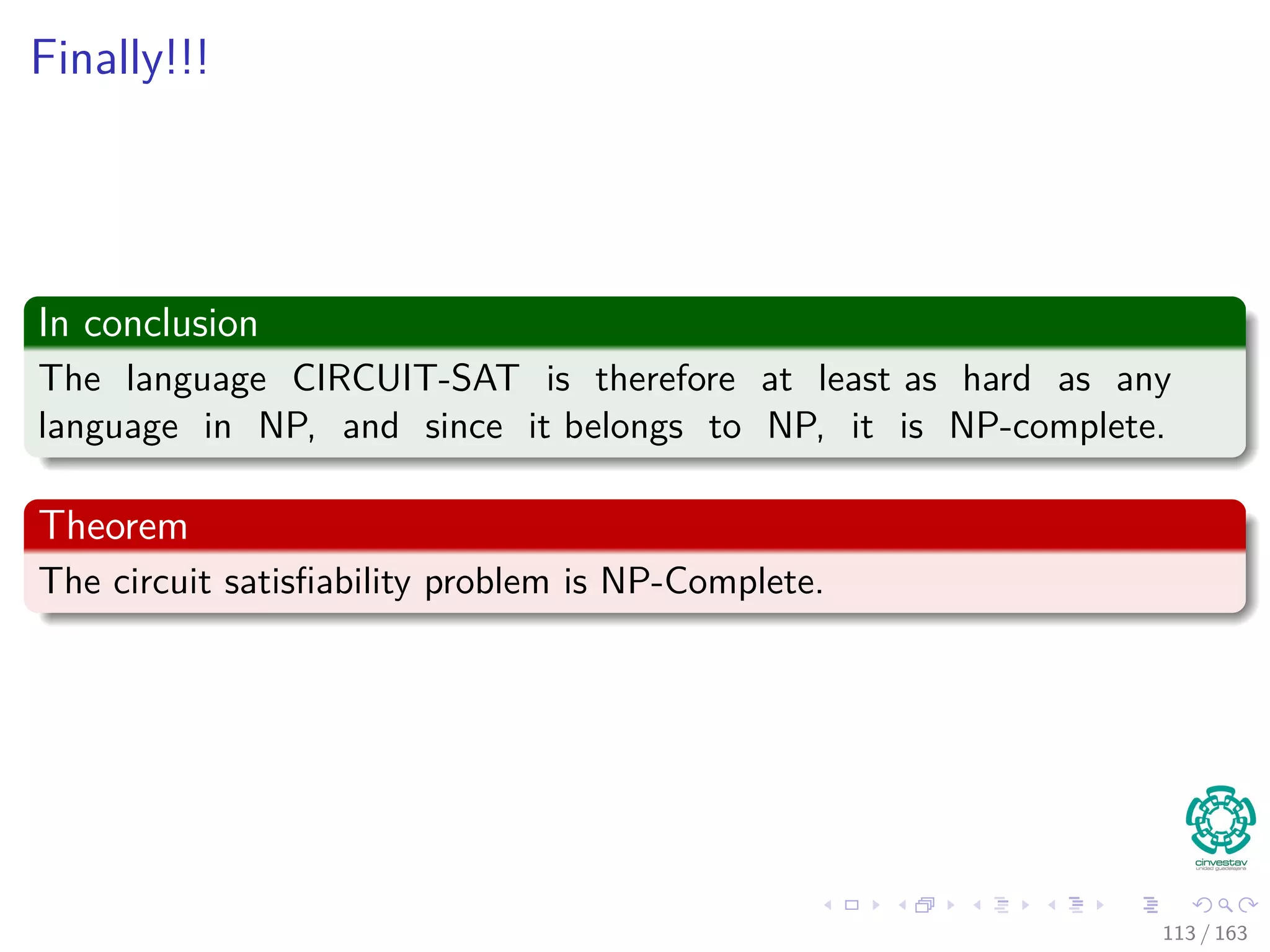

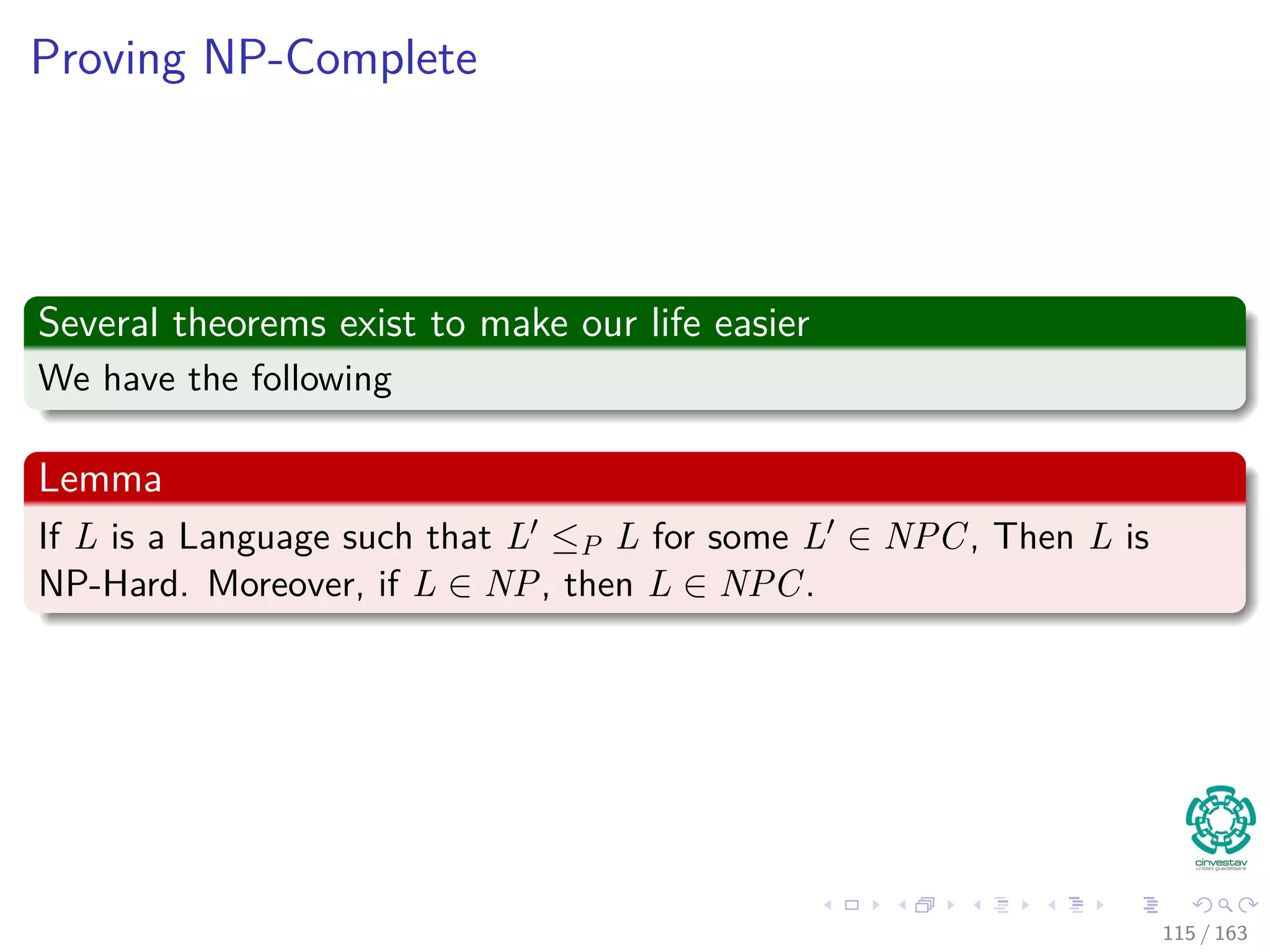

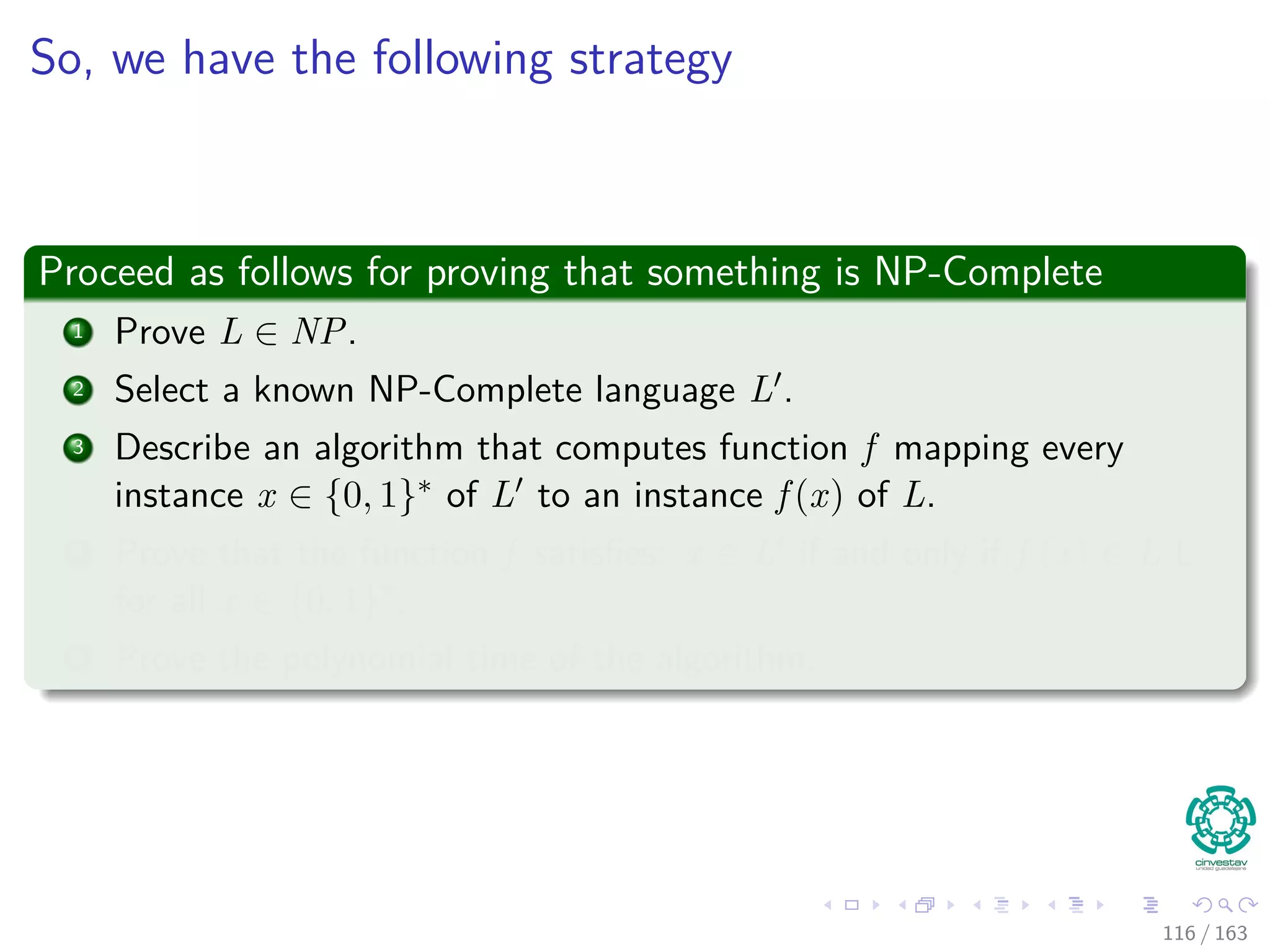

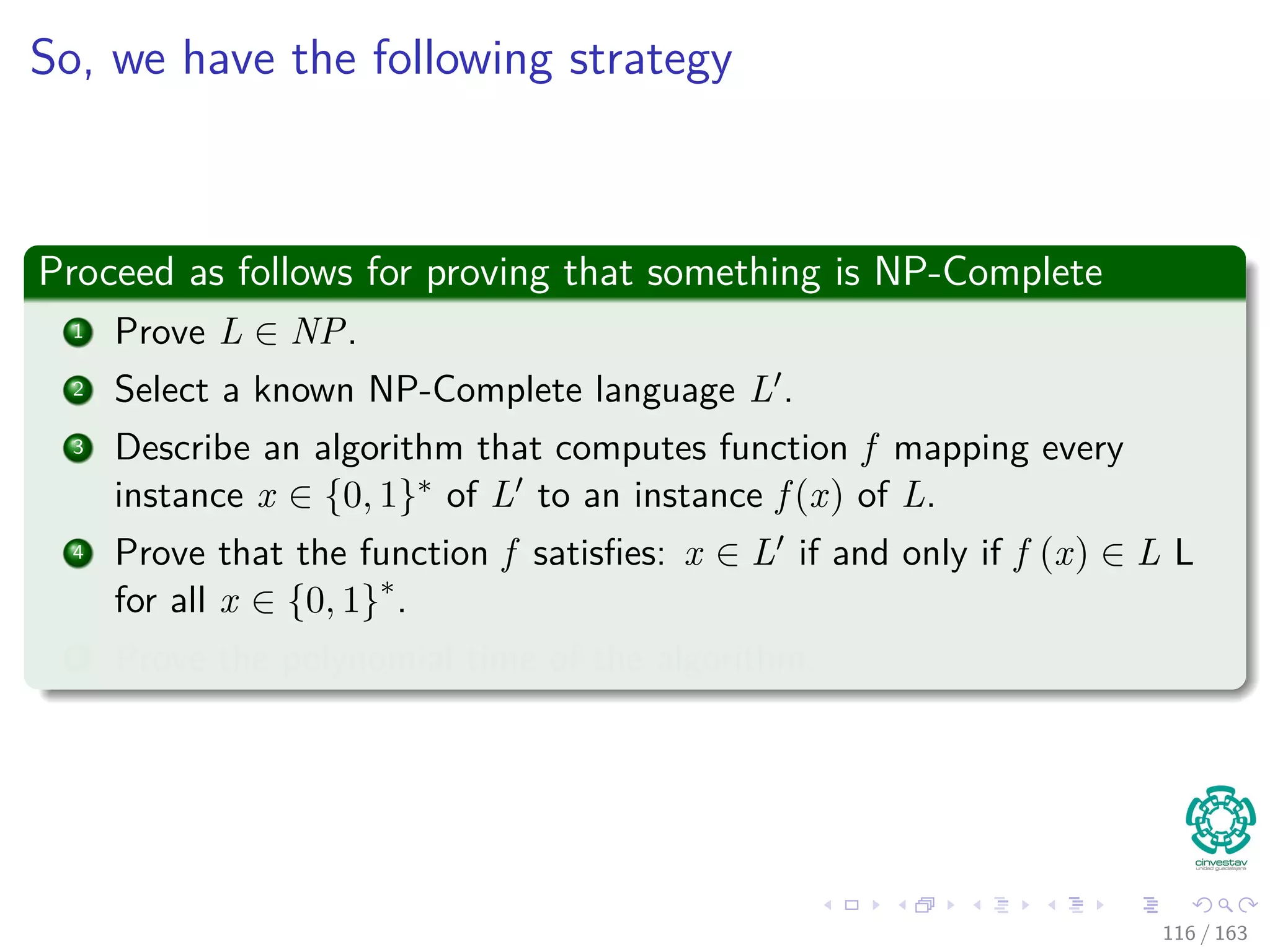

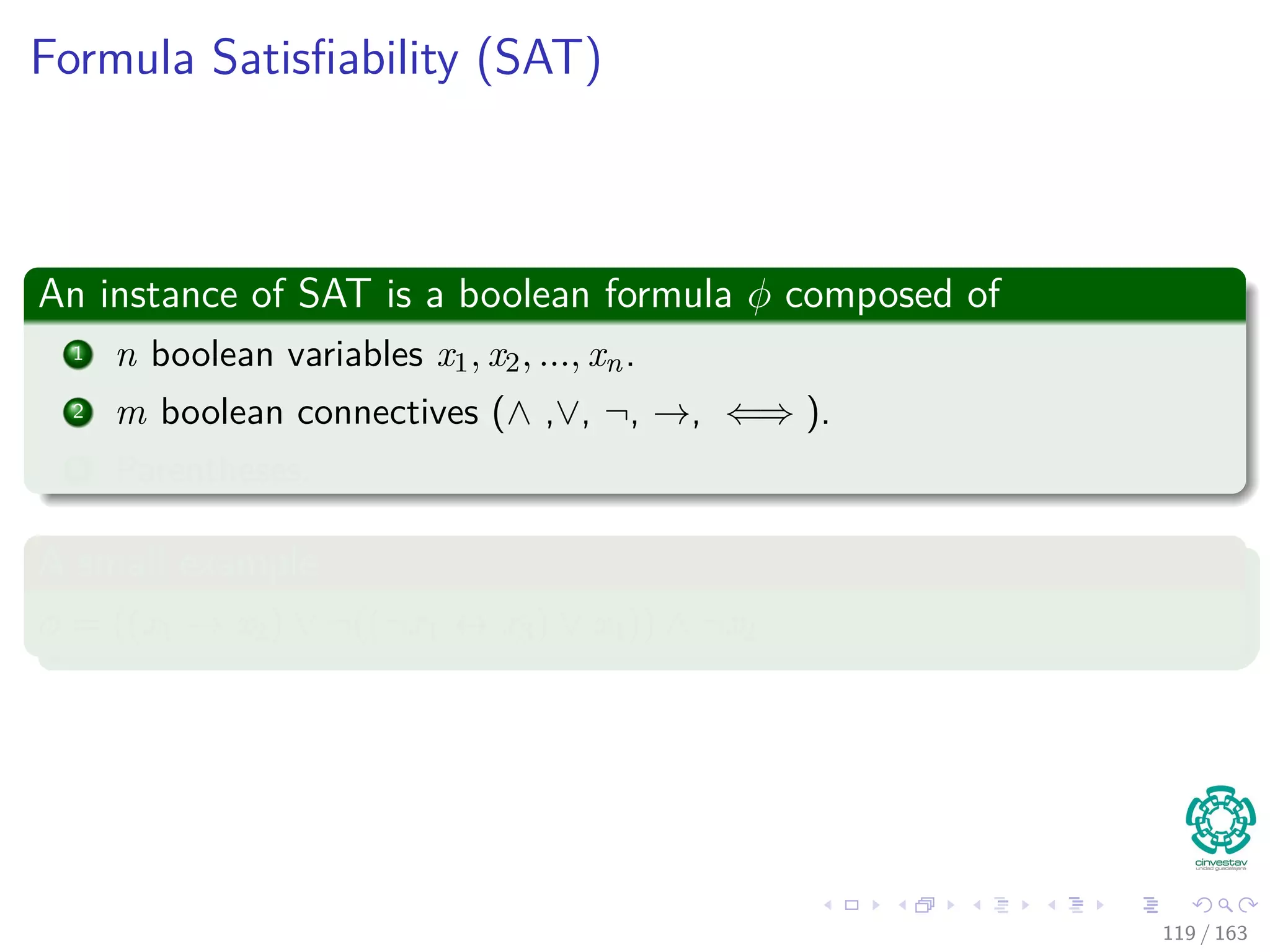

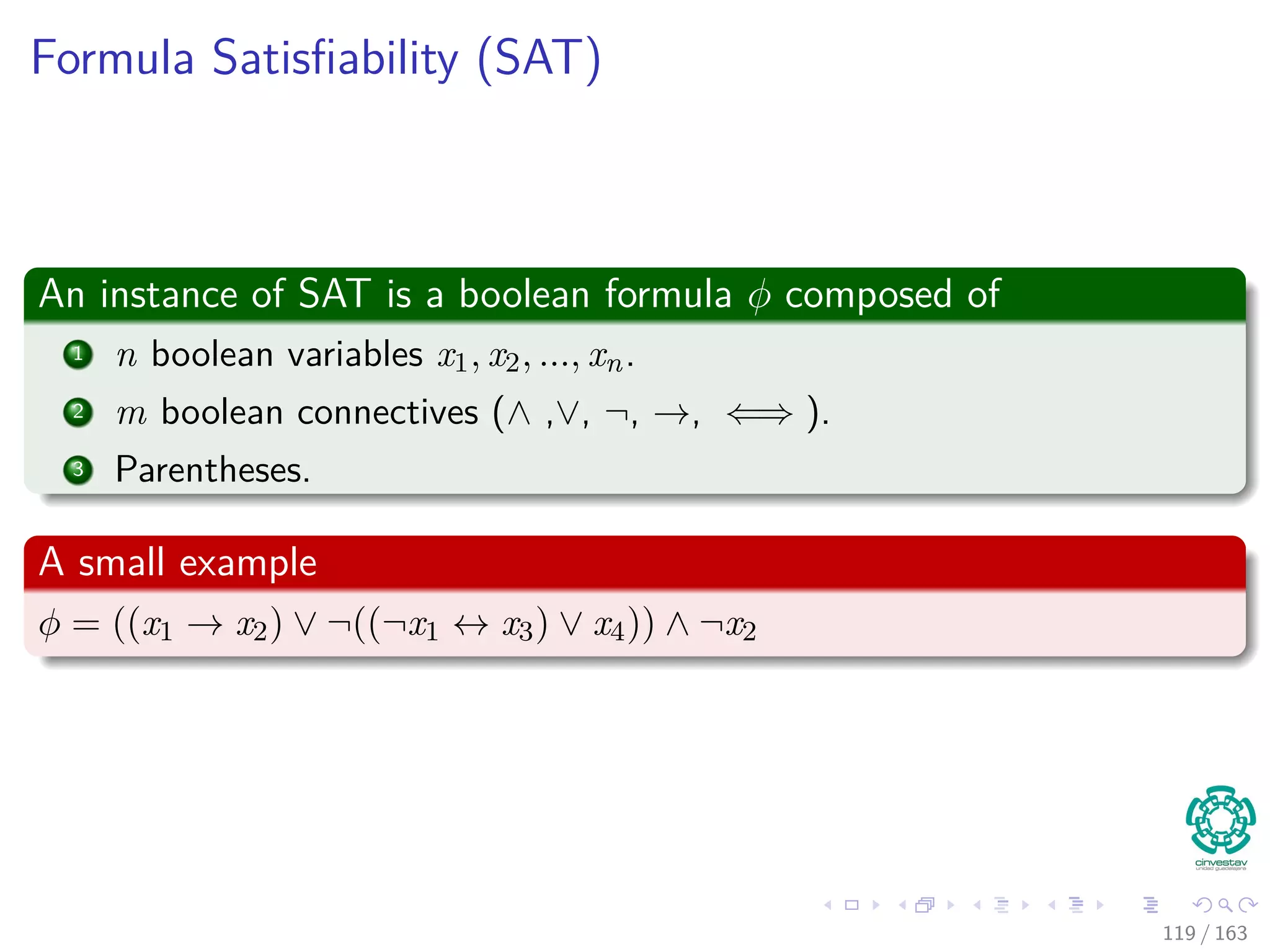

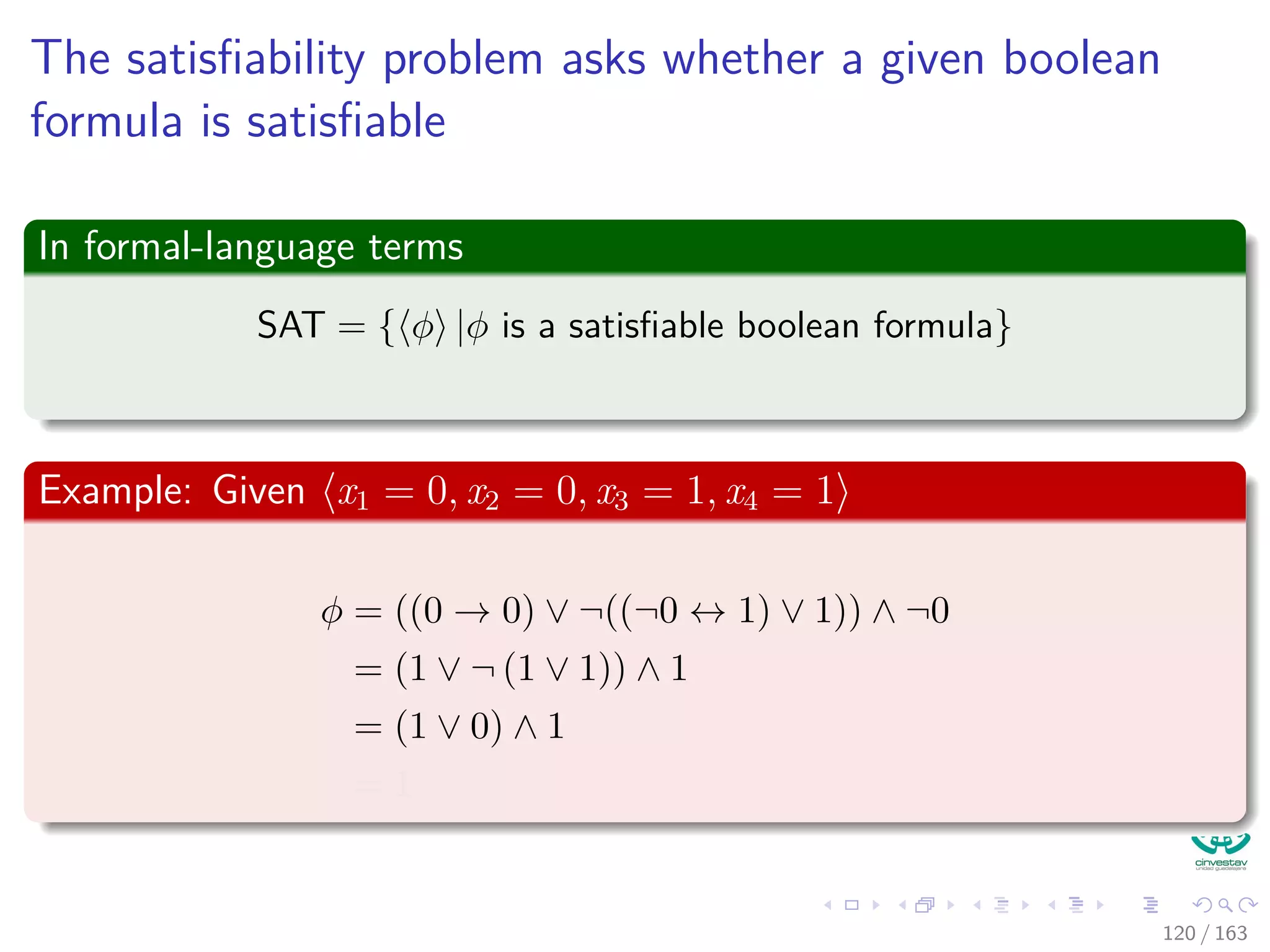

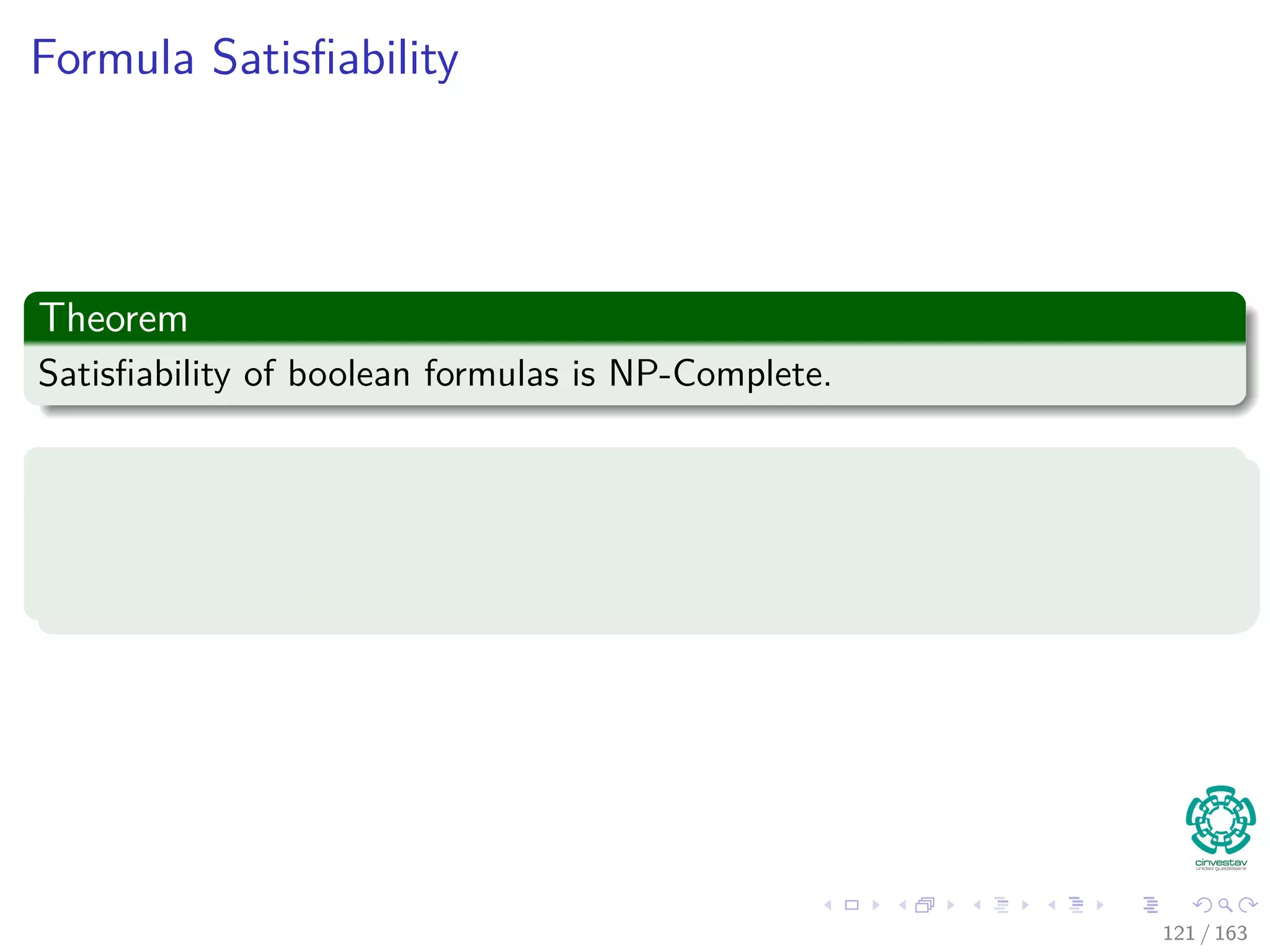

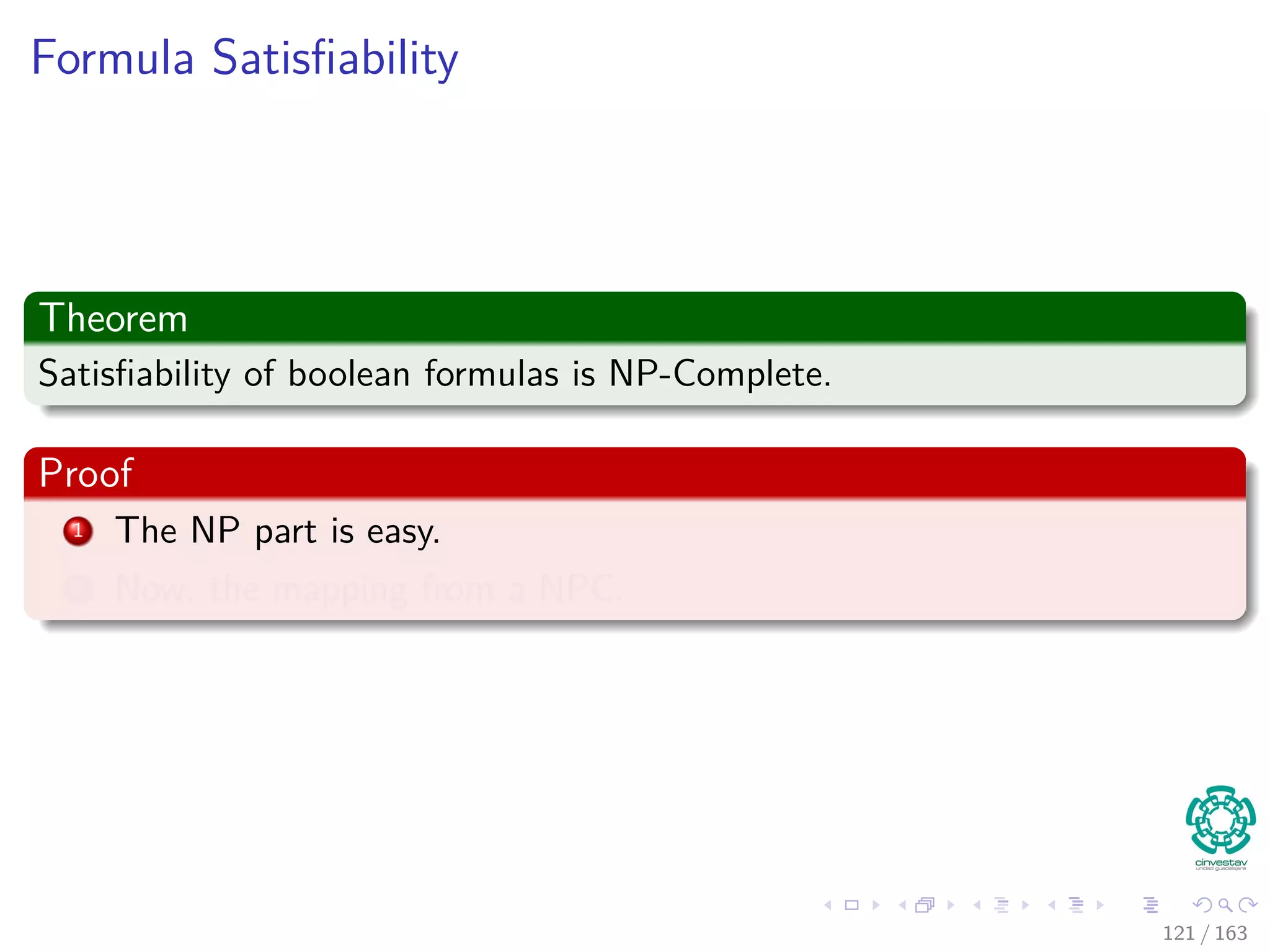

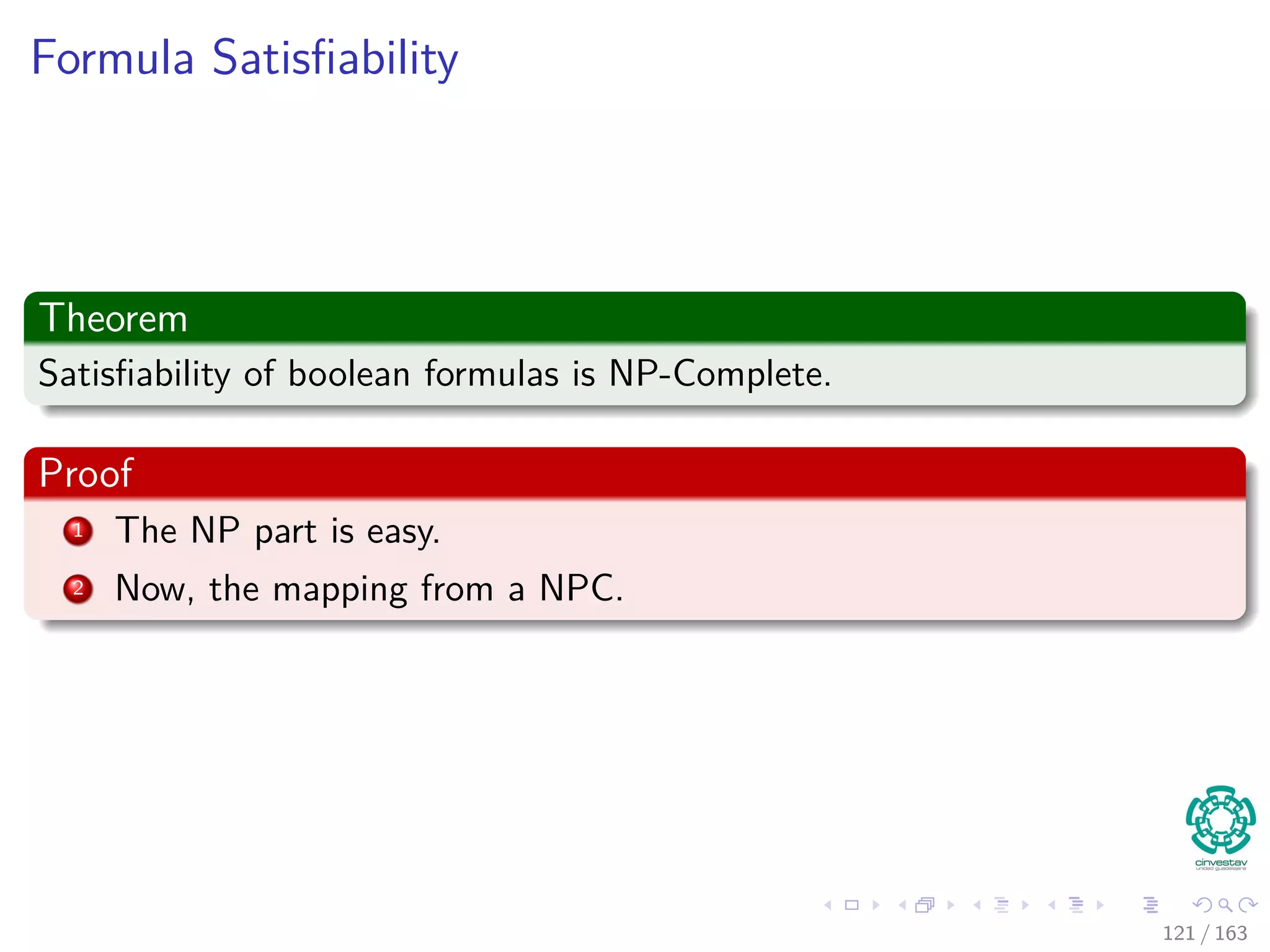

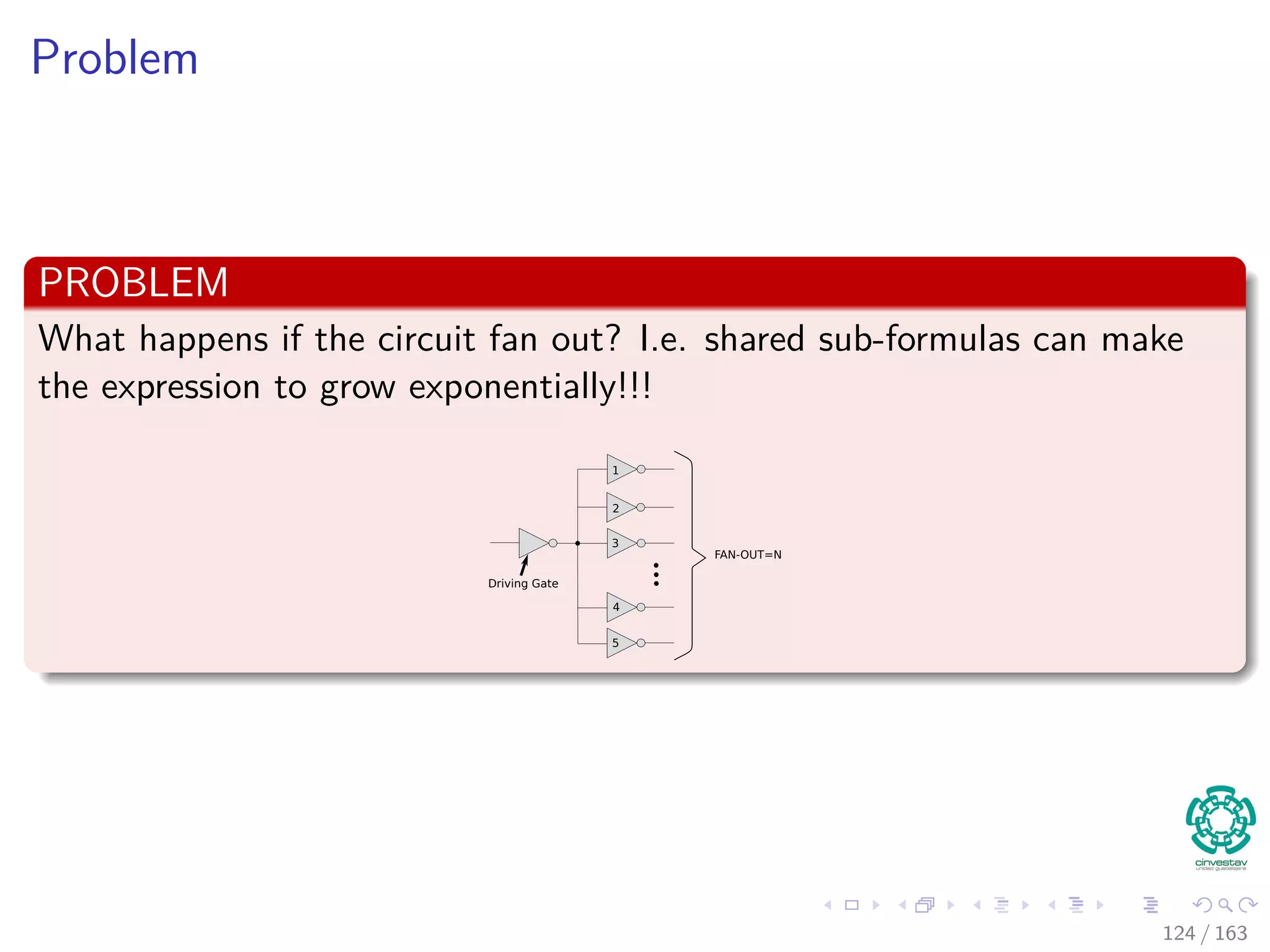

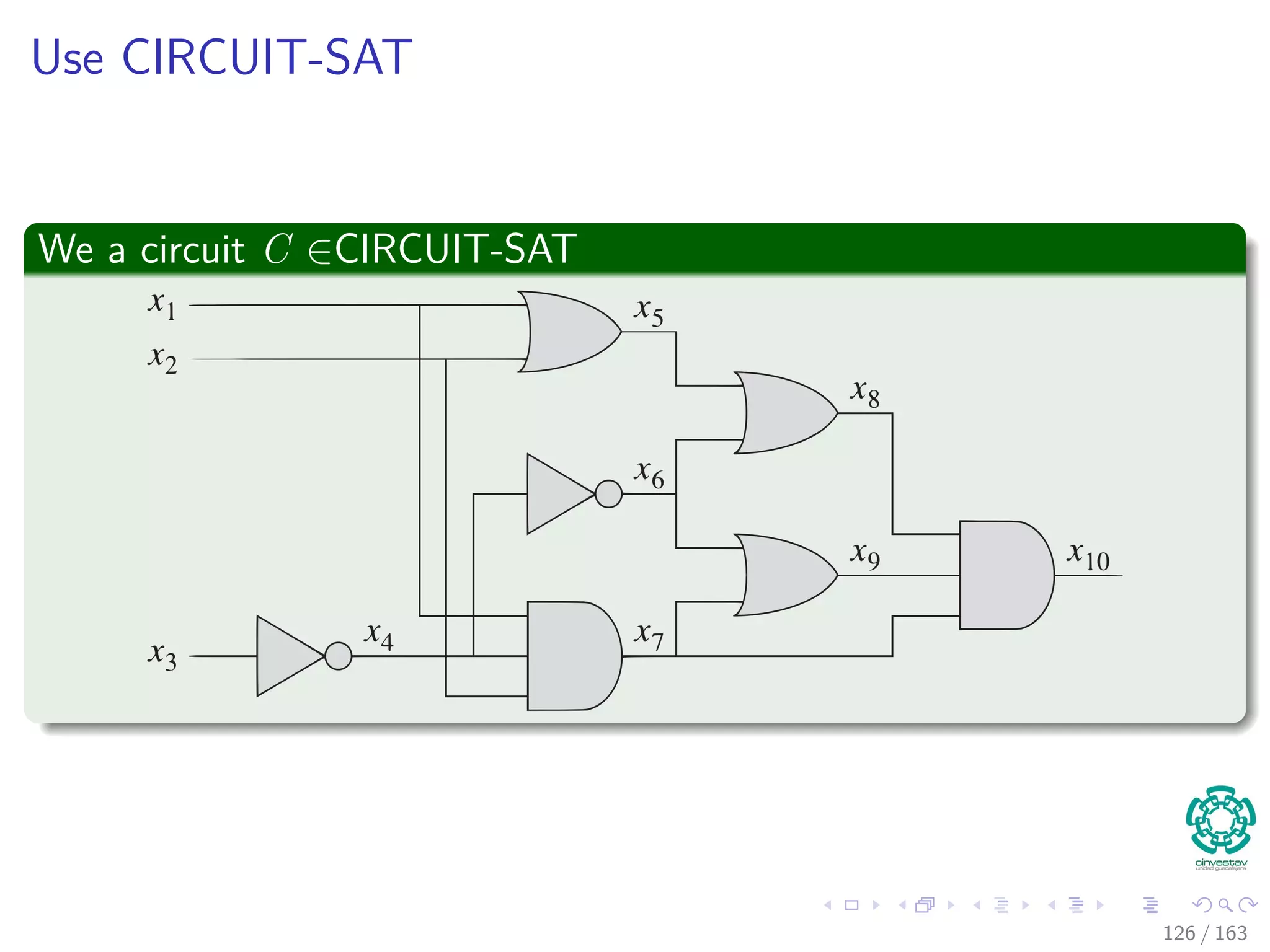

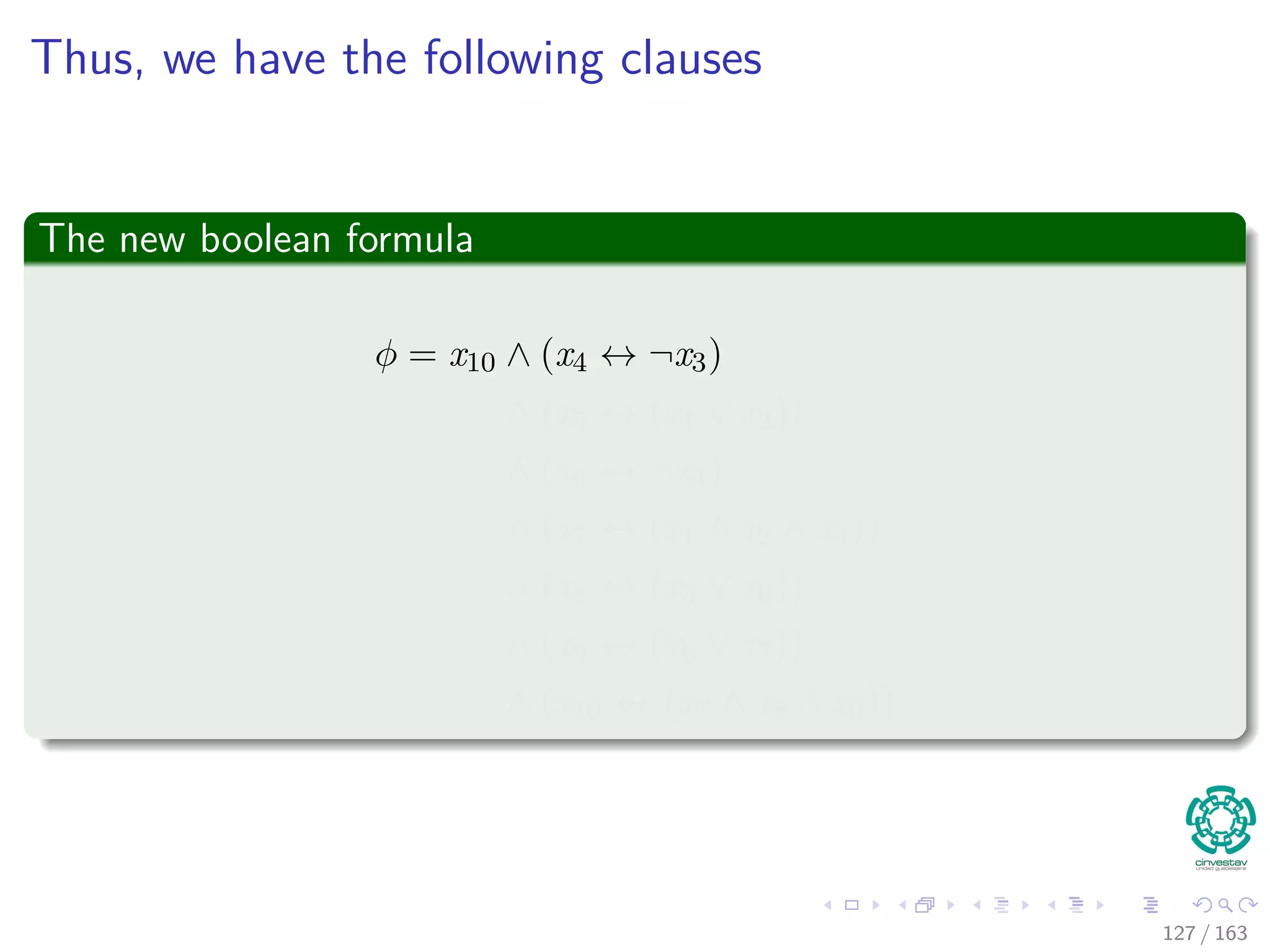

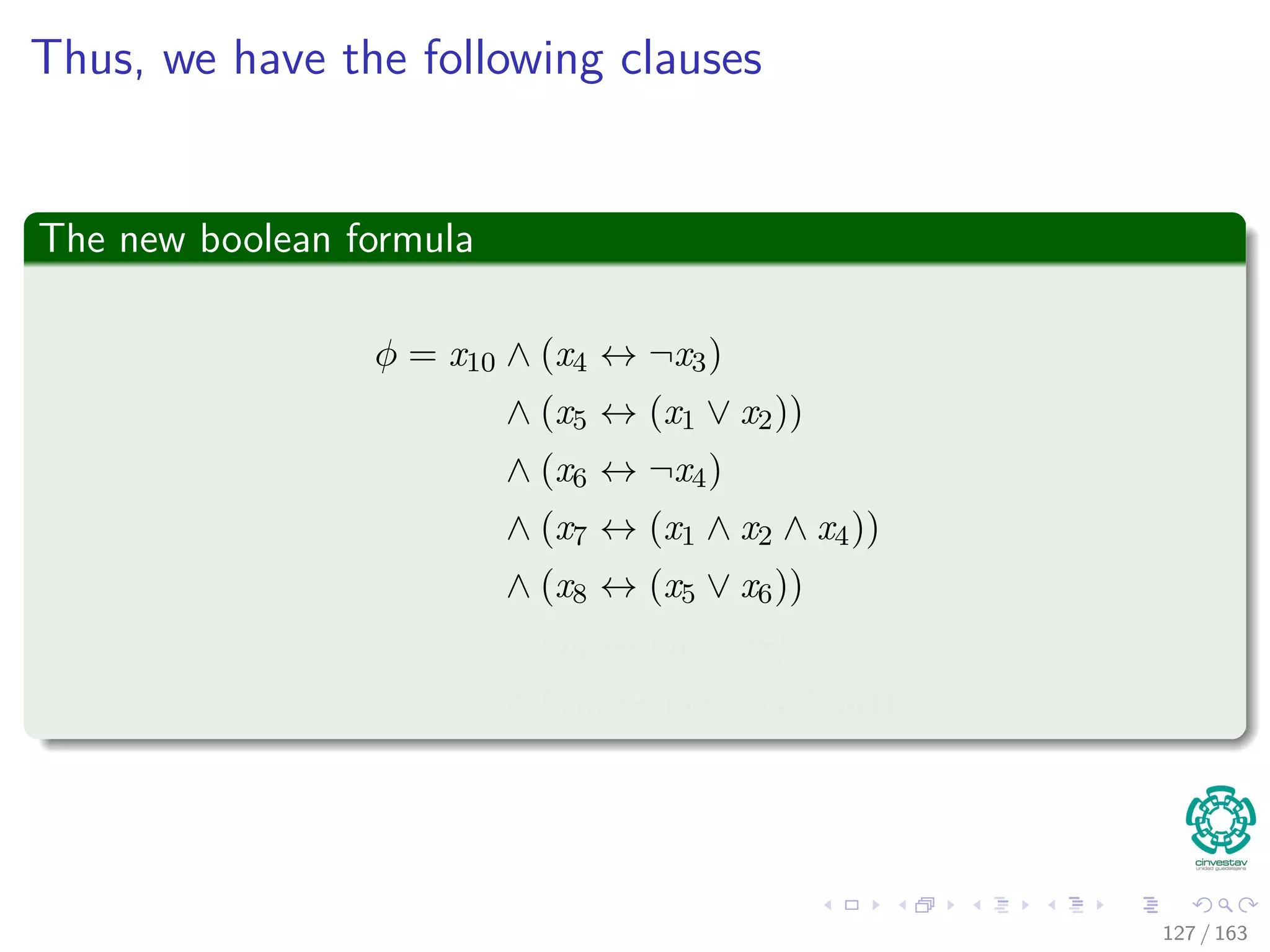

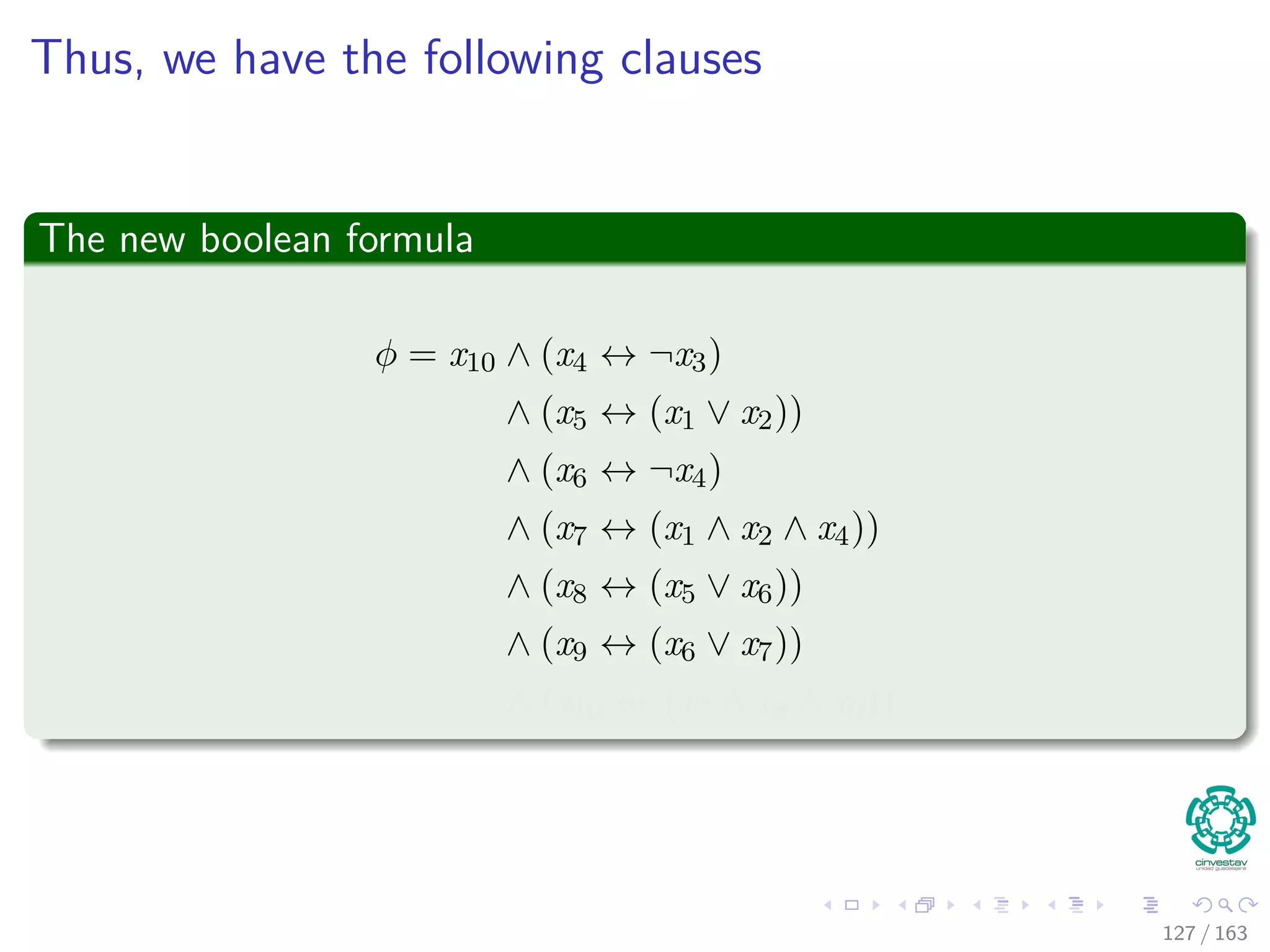

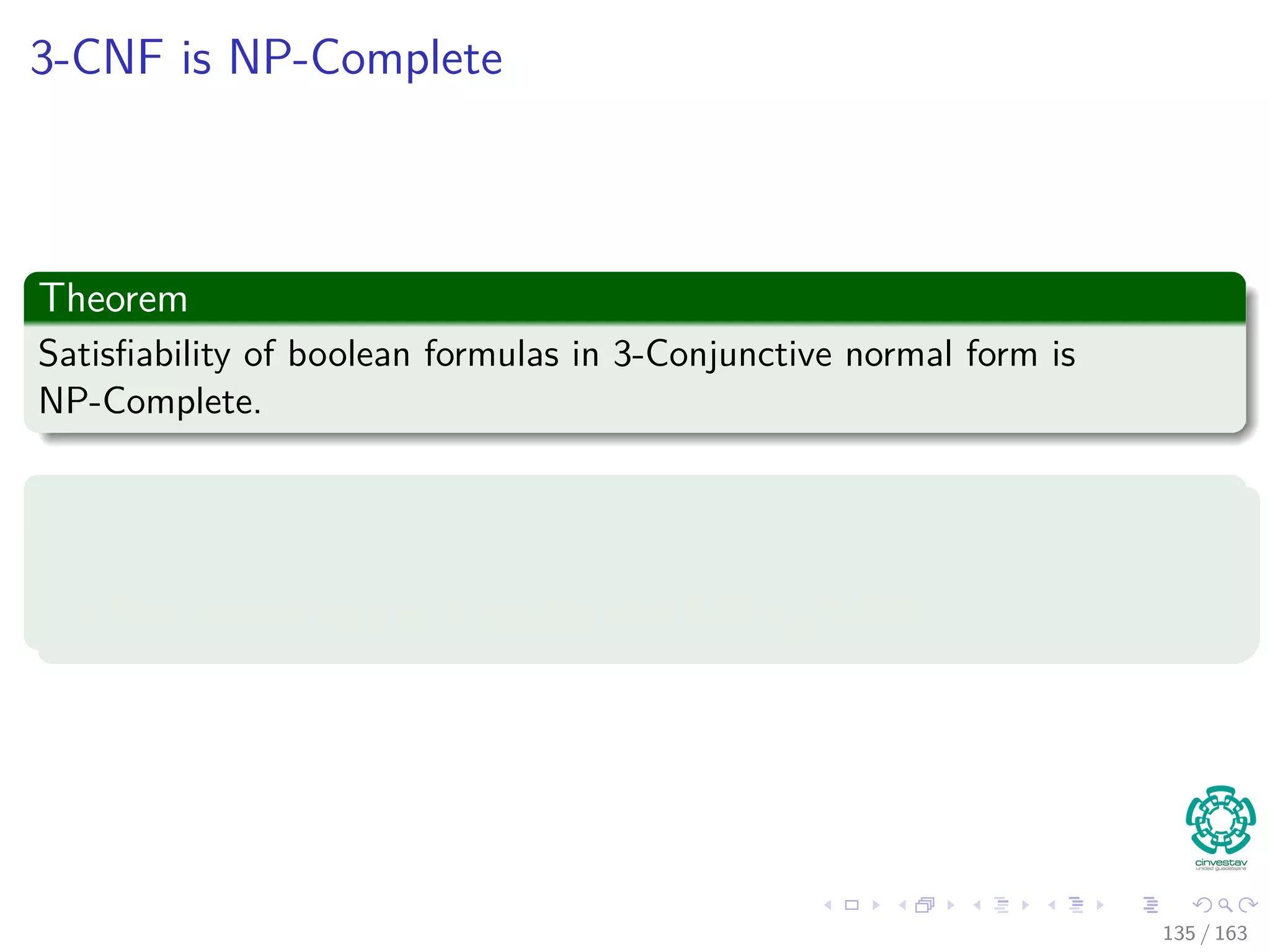

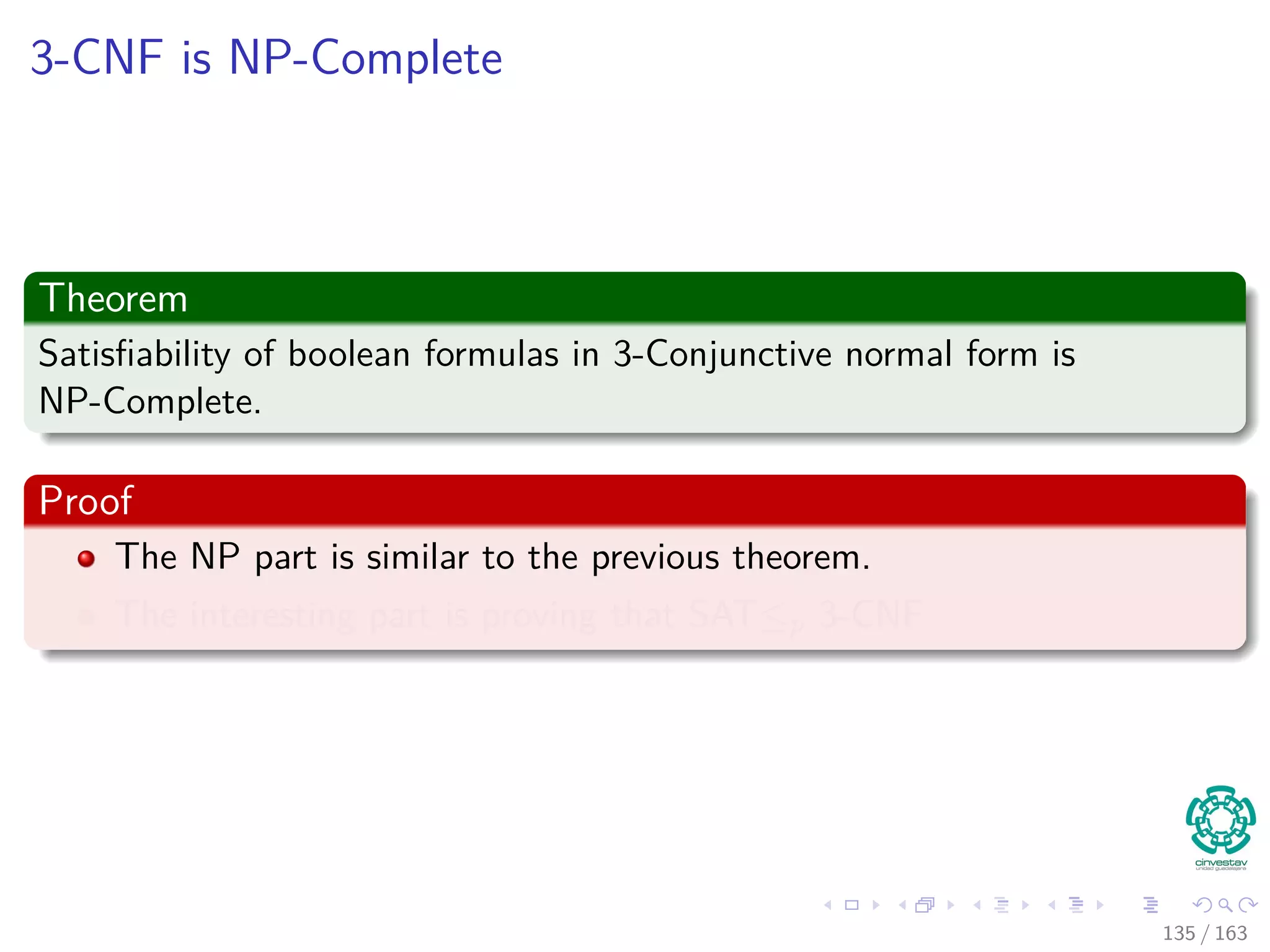

The document discusses the complexity of algorithms, particularly focusing on NP-completeness and the distinction between polynomial time (P) and non-polynomial time (NP). It outlines key concepts including polynomial time verification, reducibility, and specific NP-complete problems such as circuit satisfiability and the clique problem. It emphasizes the significance of encoding problems in a way that computational models can understand, highlighting the philosophical considerations behind classifying problems as tractable or intractable.

![In a more formal way

We have the following optimization problem

min

t

d [t]

s.t.d[v] ≤ d[u] + w(u, v) for each edge (u, v) ∈ E

d [s] = 0

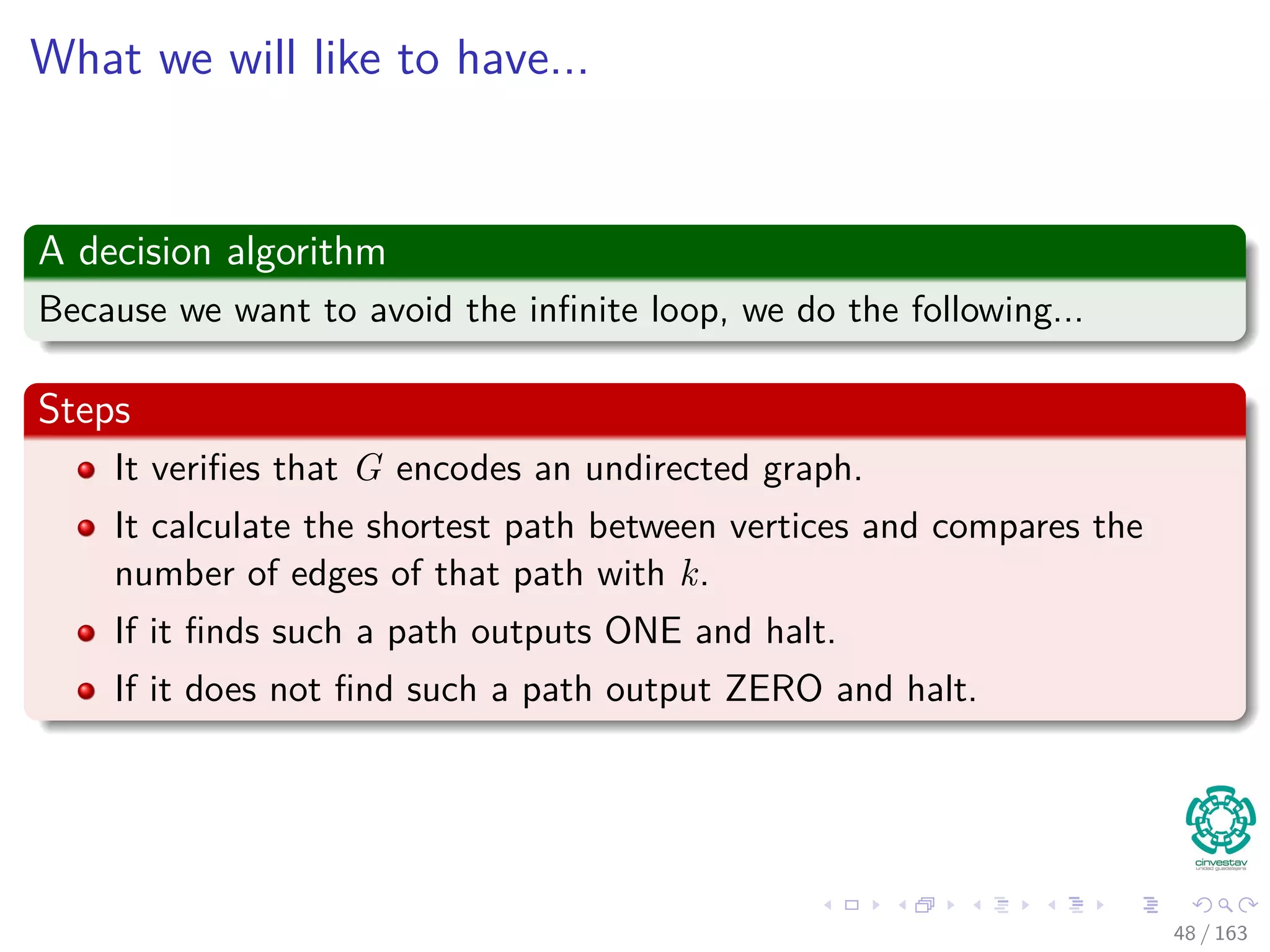

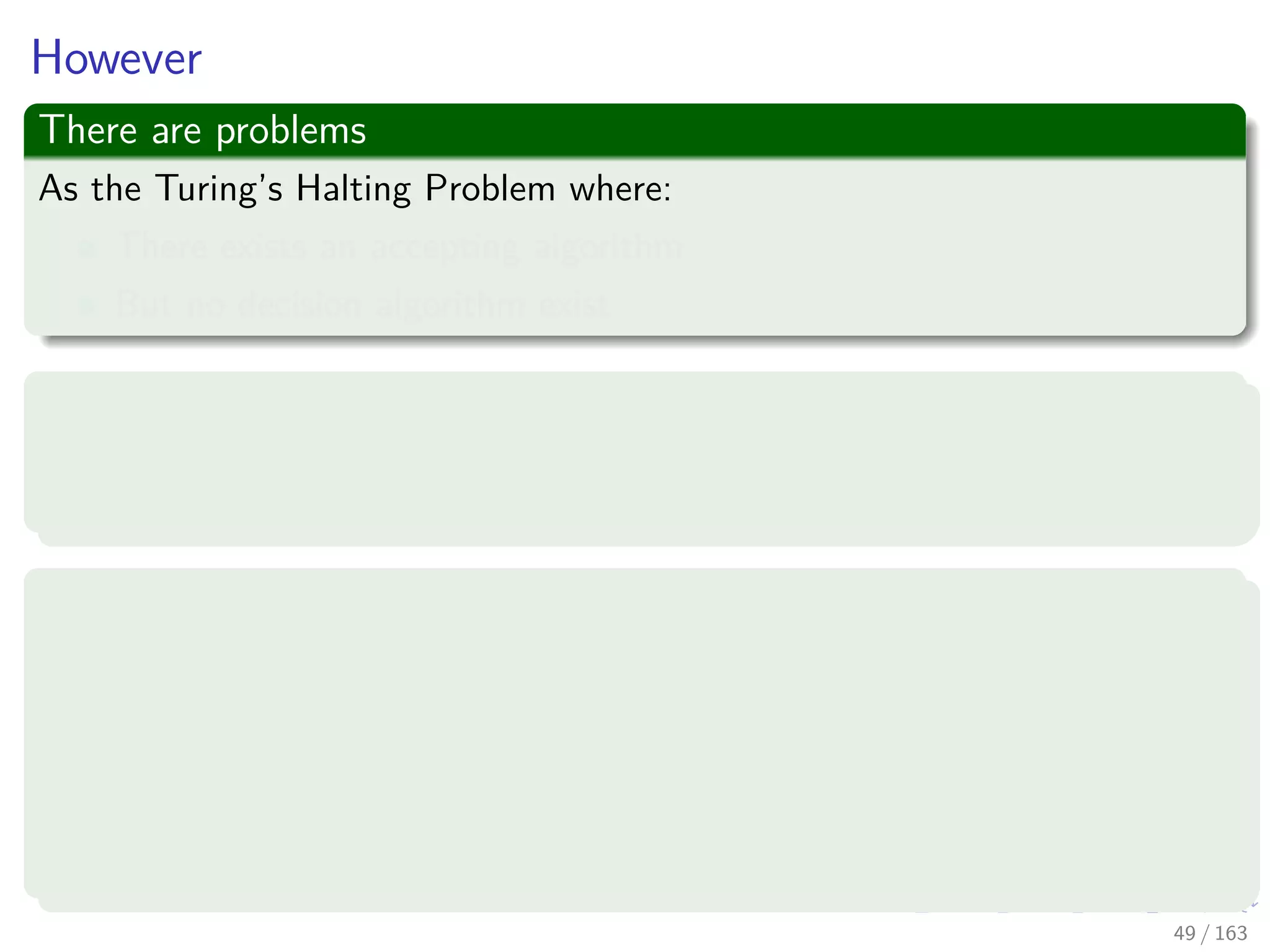

Then, we have the following decision problem

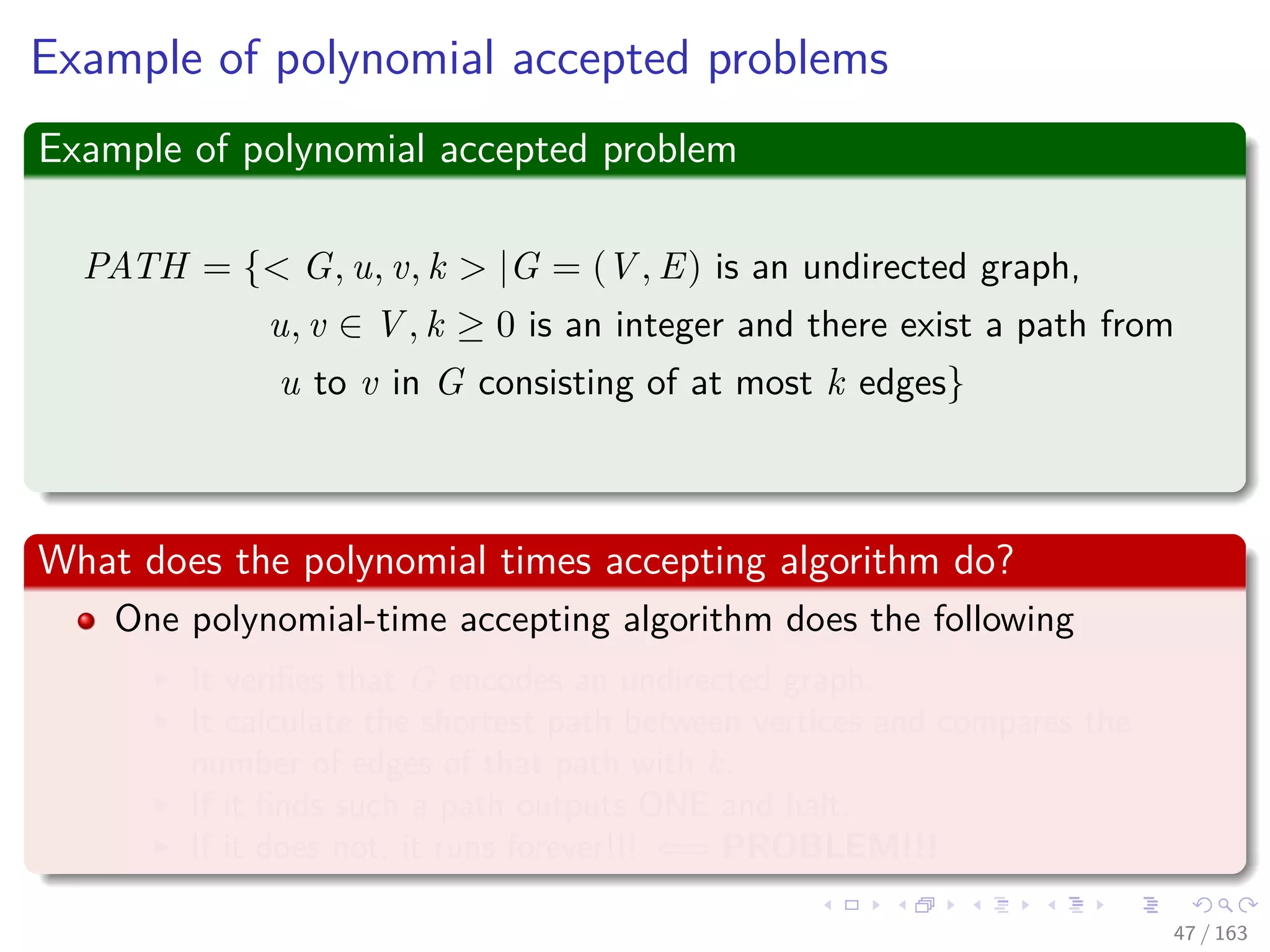

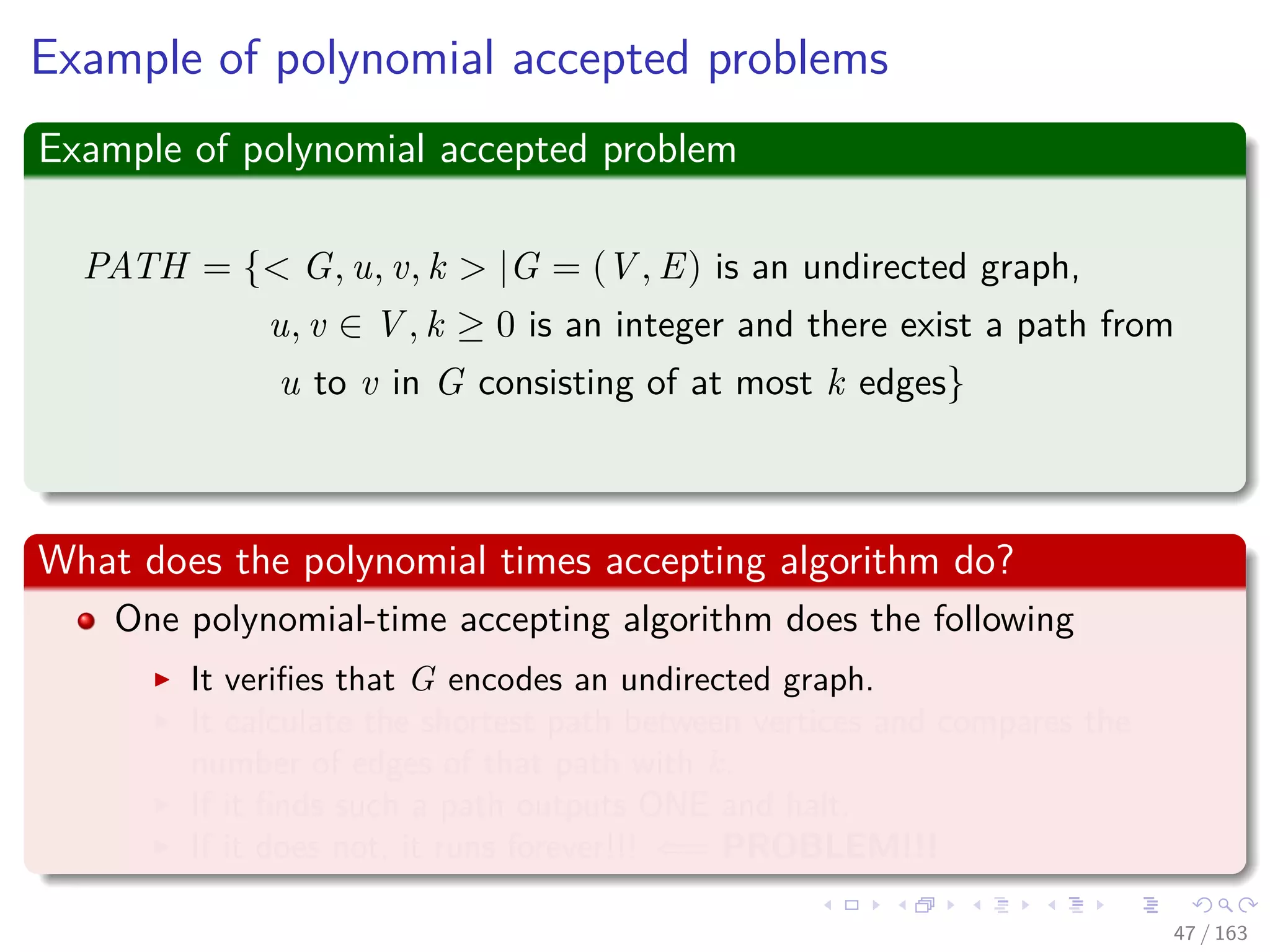

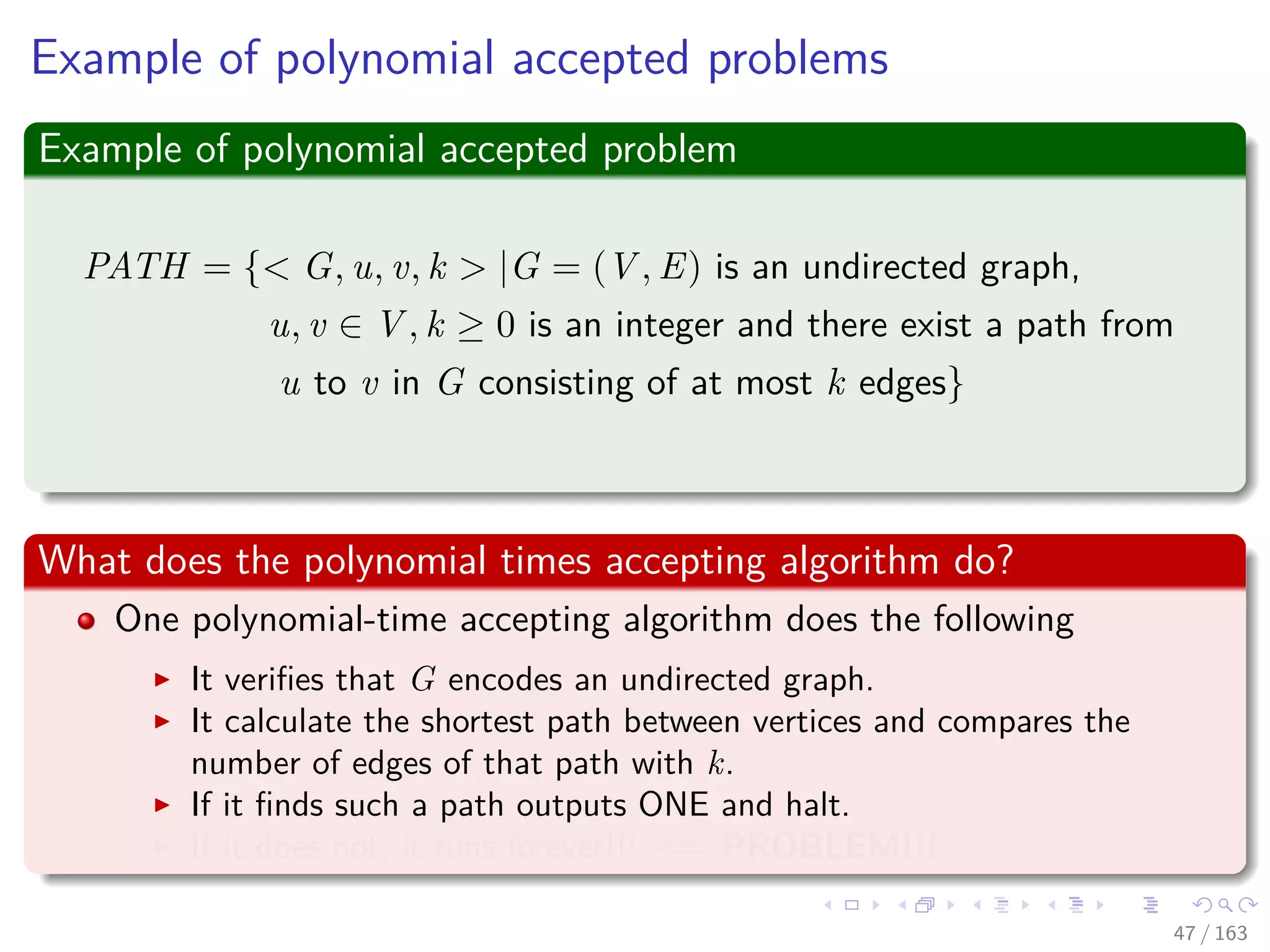

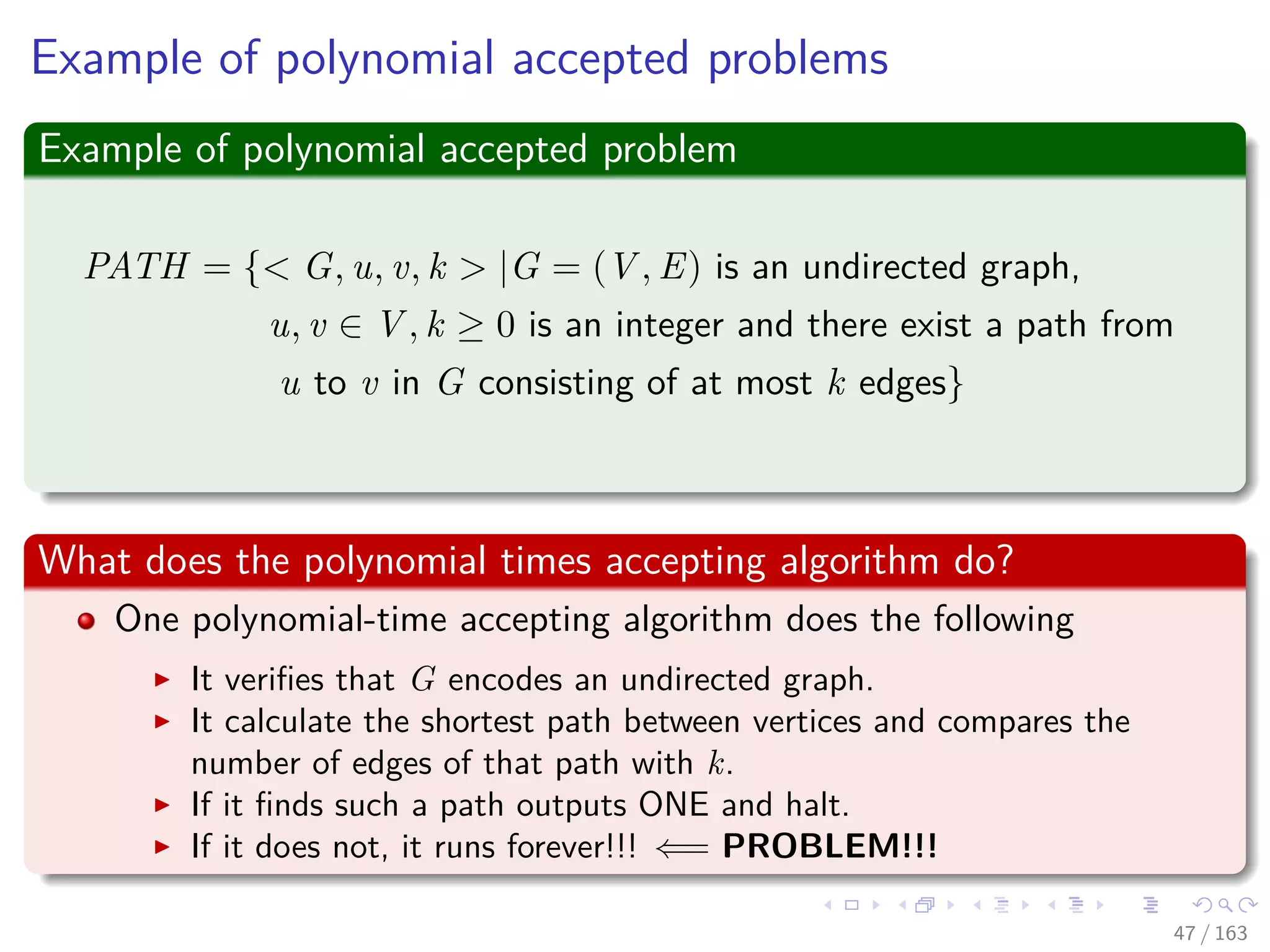

PATH = { G, u, v, k |G = (V , E) is an undirected graph,

u, v ∈ V , k ≥ 0 is an integer and there exist a path from

u to v in G consisting of at most k edges}

22 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-40-2048.jpg)

![In a more formal way

We have the following optimization problem

min

t

d [t]

s.t.d[v] ≤ d[u] + w(u, v) for each edge (u, v) ∈ E

d [s] = 0

Then, we have the following decision problem

PATH = { G, u, v, k |G = (V , E) is an undirected graph,

u, v ∈ V , k ≥ 0 is an integer and there exist a path from

u to v in G consisting of at most k edges}

22 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-41-2048.jpg)

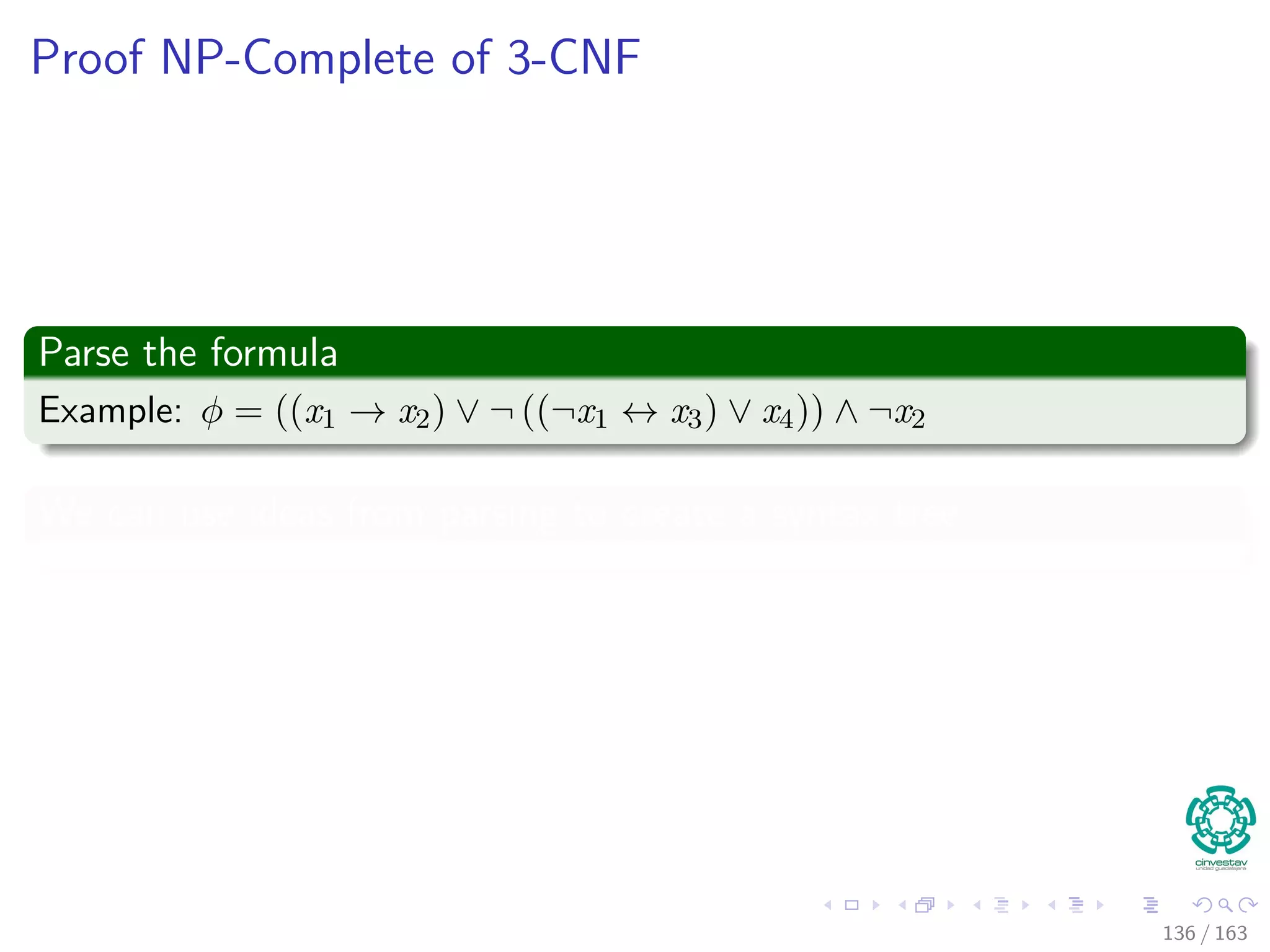

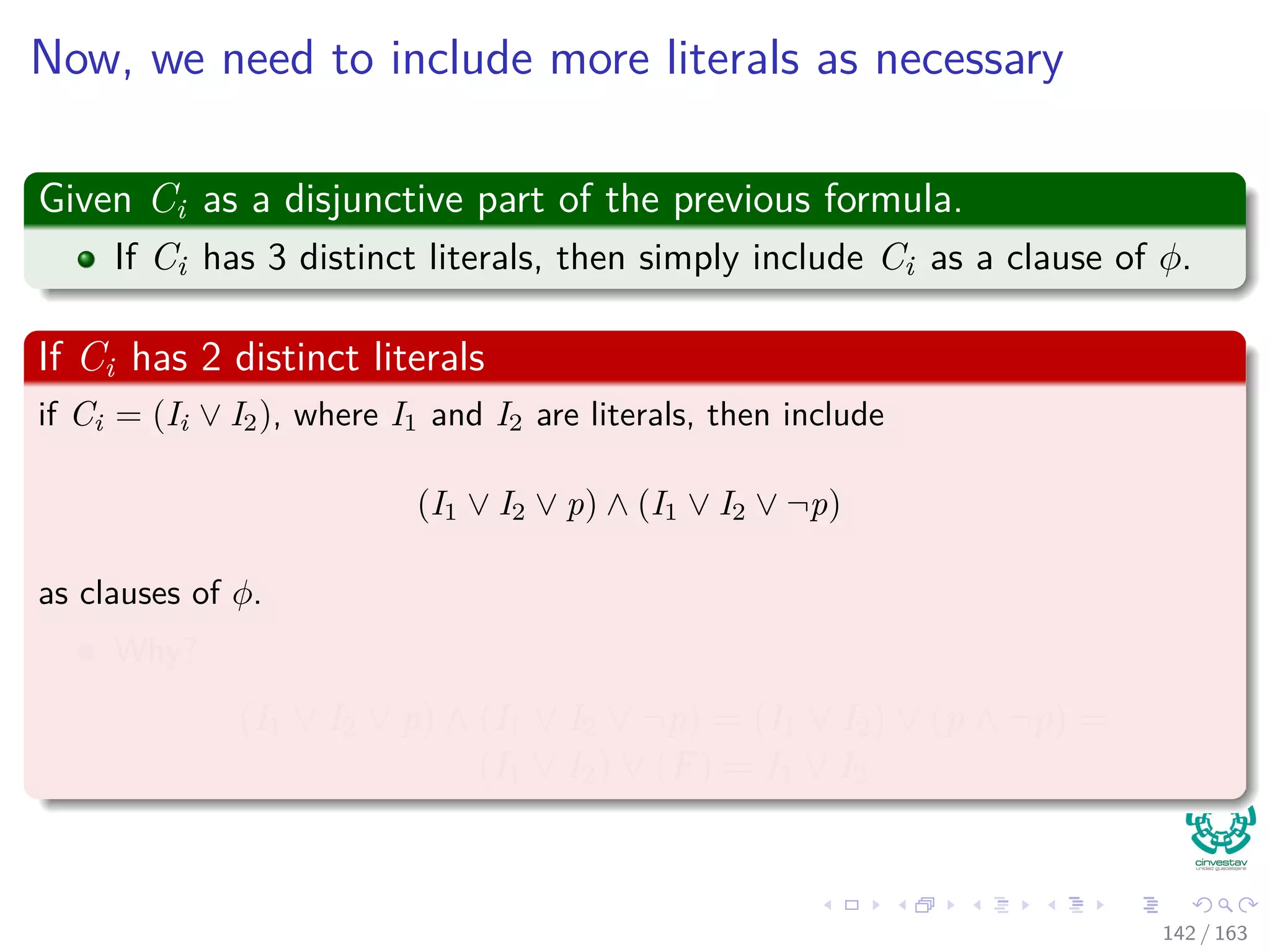

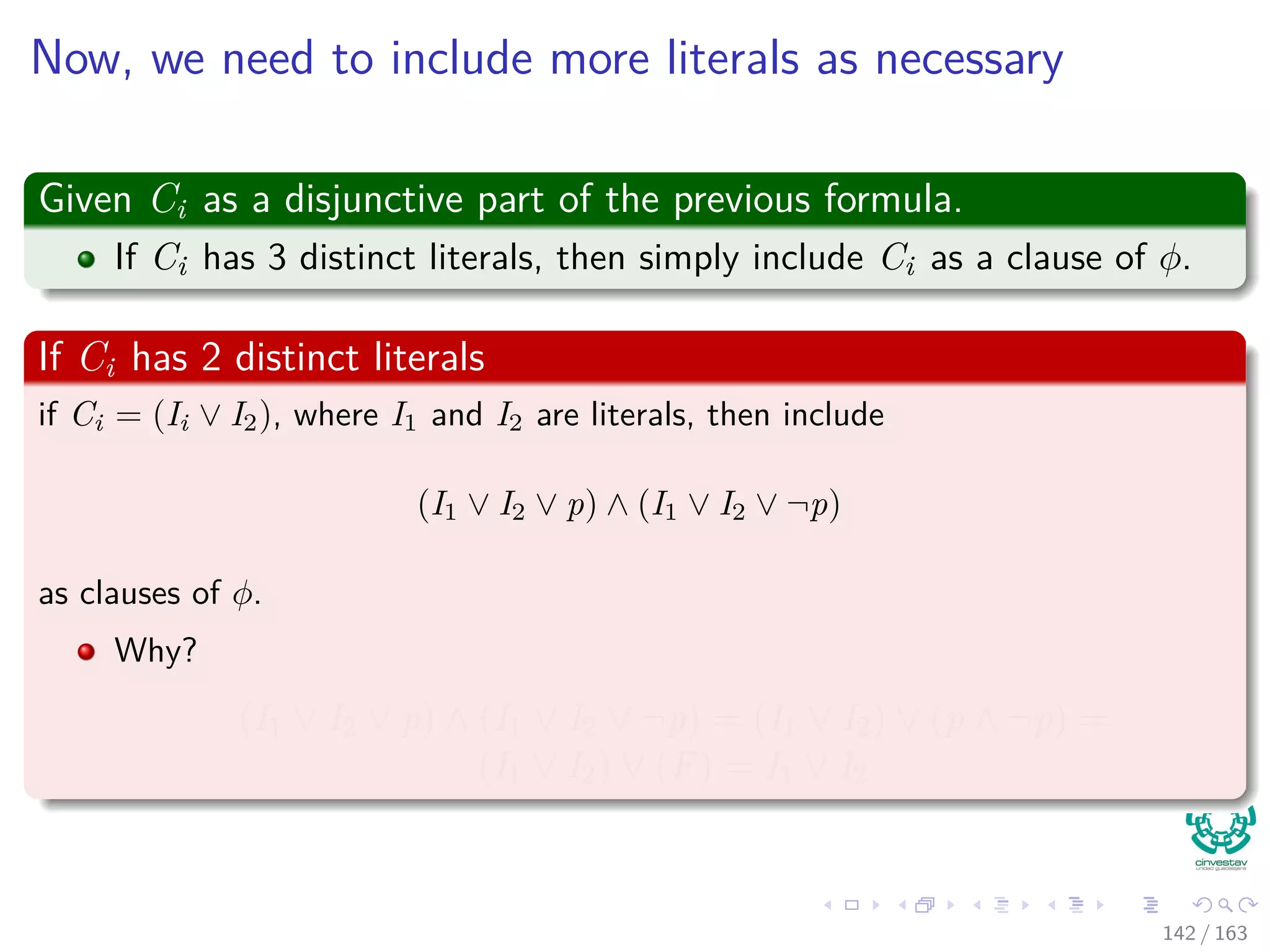

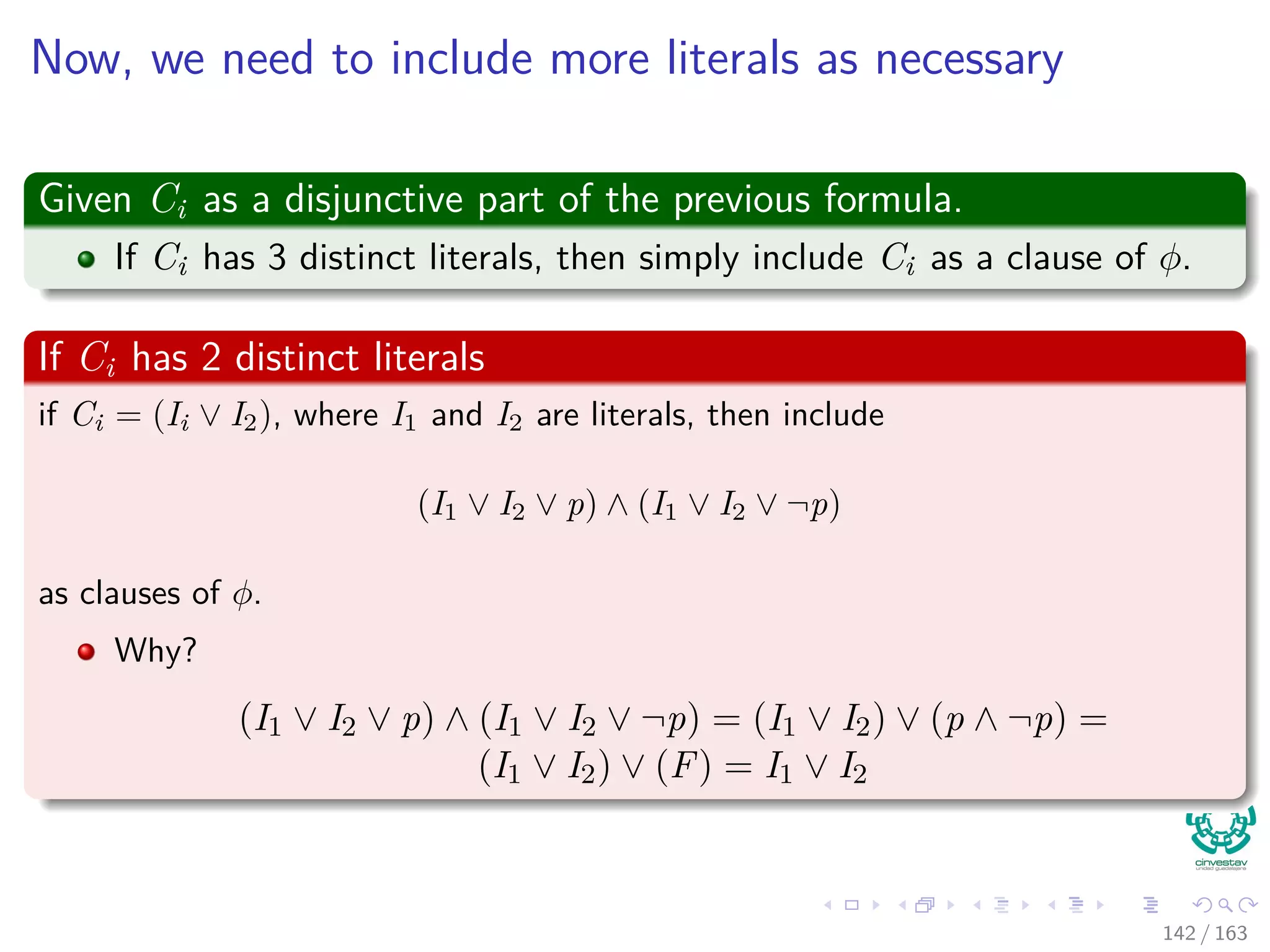

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-353-2048.jpg)

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-354-2048.jpg)

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-355-2048.jpg)

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-356-2048.jpg)

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-357-2048.jpg)

![Now, we need to include more literals as necessary

If Ci has just 1 distinct literal I

Then include (I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q)

as clauses of φ.

Why?

(I ∨ p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ p ∨ ¬q)∧...

(I ∨ ¬p ∨ q) ∧ (I ∨ ¬p ∨ ¬q) = I ∨ [(p ∨ q) ∧ (p ∨ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ q) ∧ (¬p ∨ ¬q)]

= I ∨ [p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q) ∧ . . .

(¬p ∨ (q ∧ ¬q))]

= I ∨ [(p ∨ F) ∧ (¬p ∨ F)]

= I ∨ [p ∧ ¬p]

= I ∨ F = I

143 / 163](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/27npcompletness-151117121725-lva1-app6891/75/27-NP-Completness-358-2048.jpg)