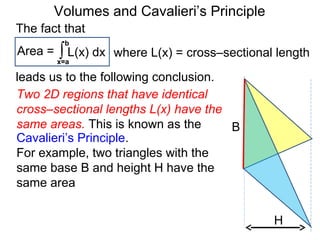

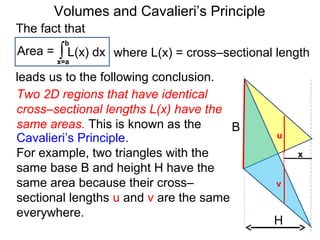

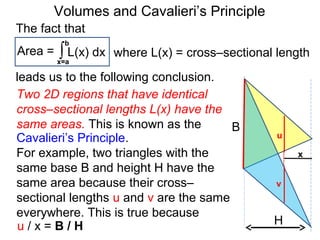

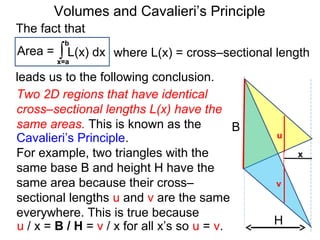

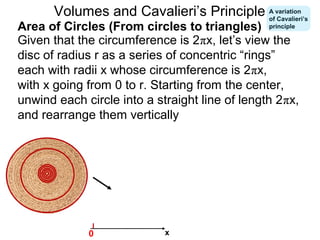

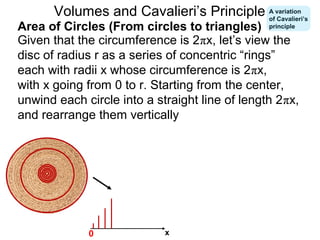

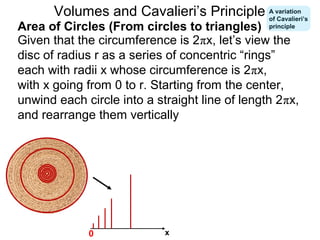

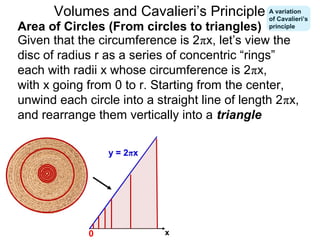

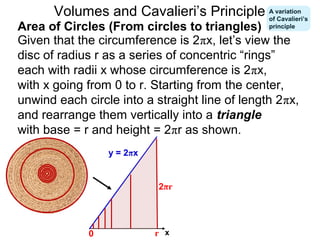

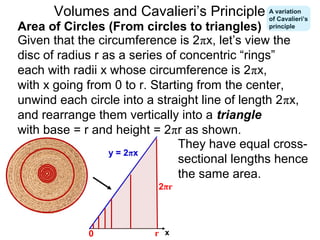

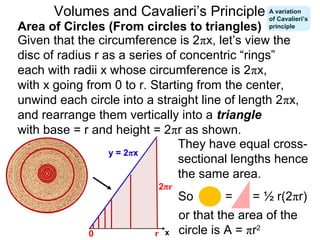

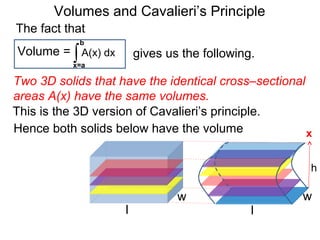

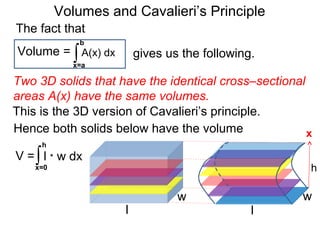

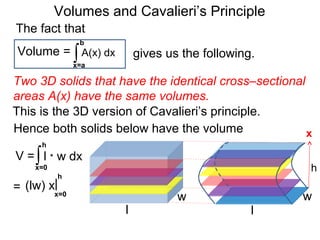

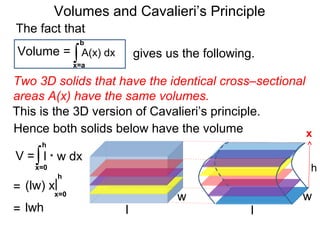

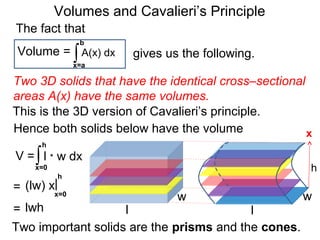

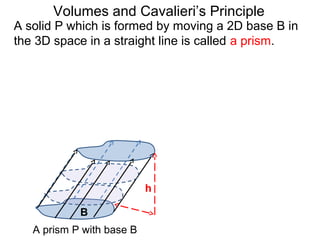

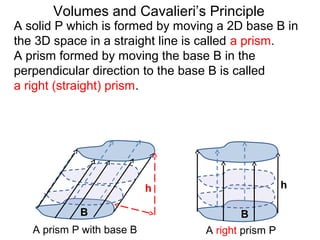

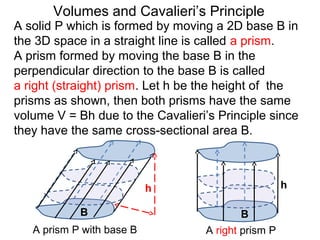

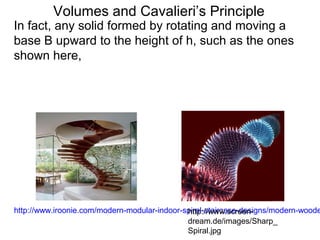

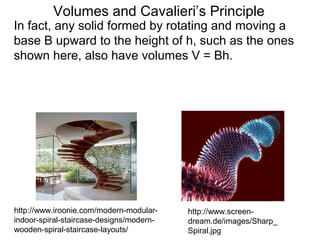

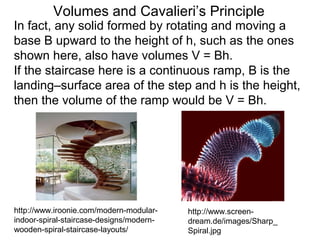

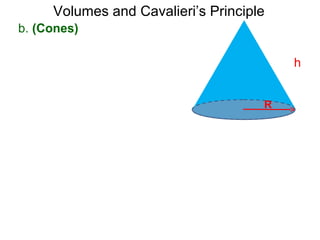

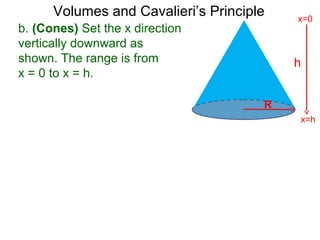

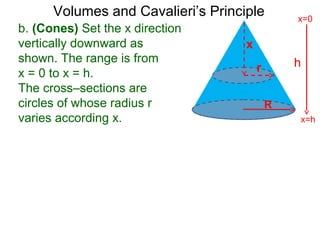

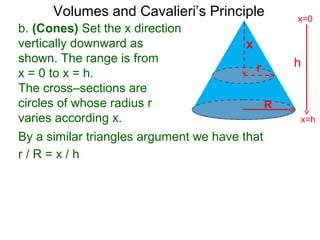

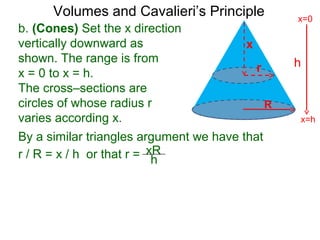

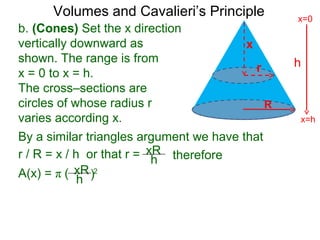

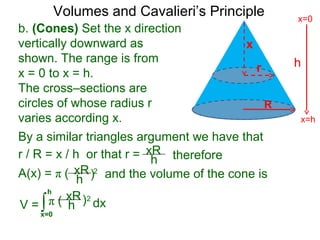

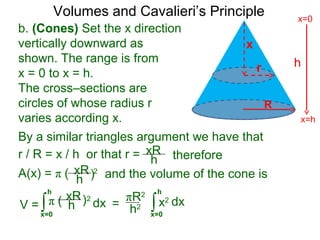

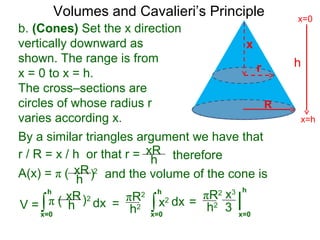

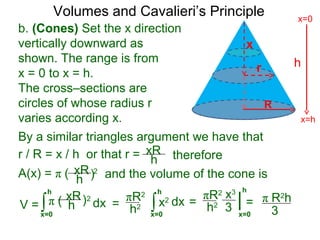

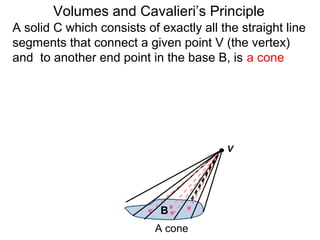

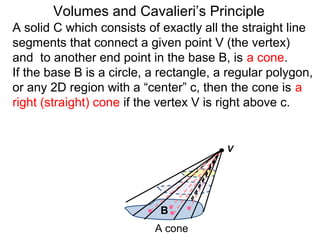

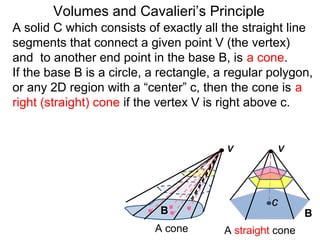

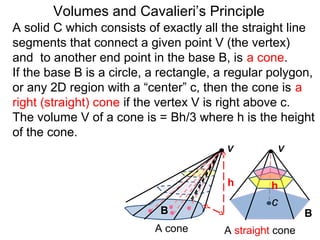

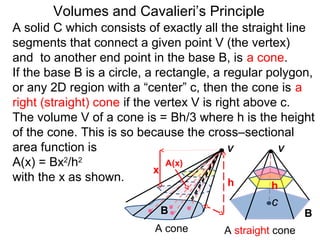

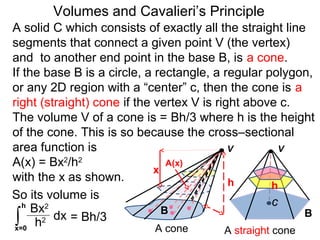

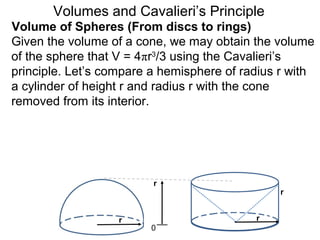

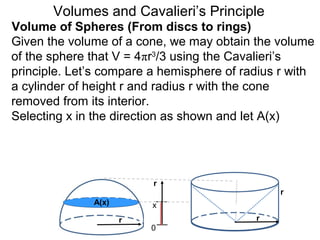

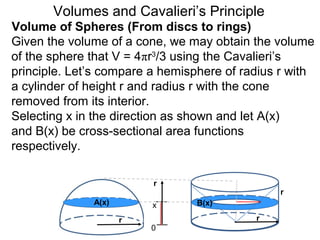

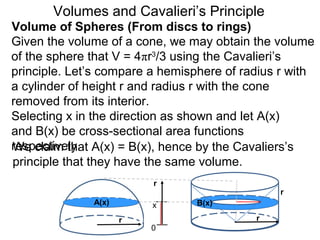

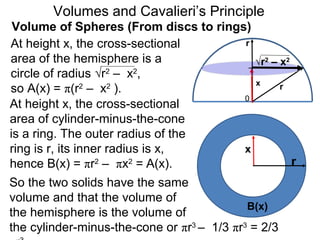

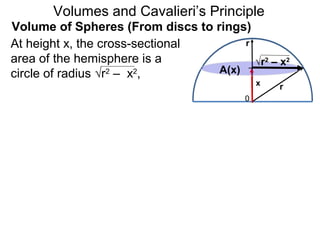

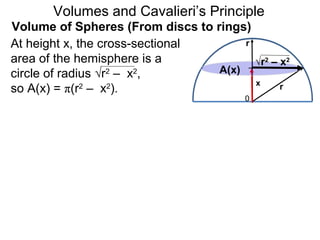

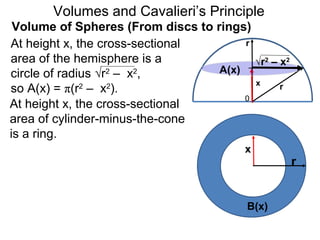

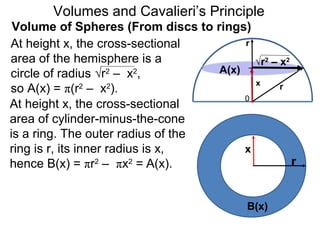

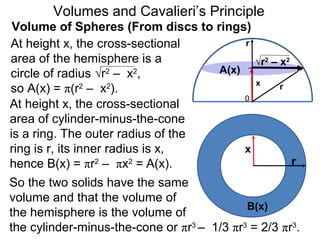

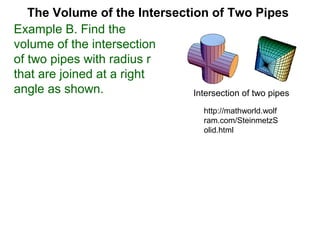

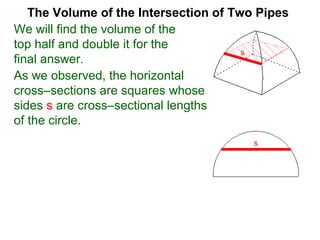

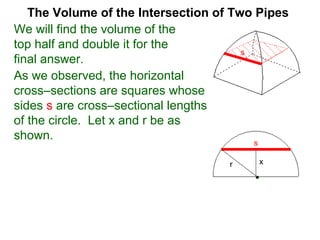

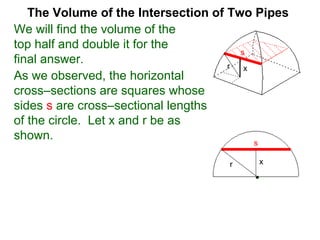

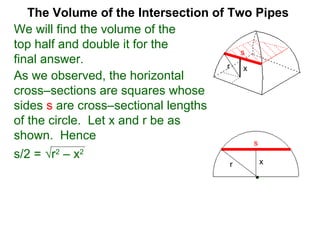

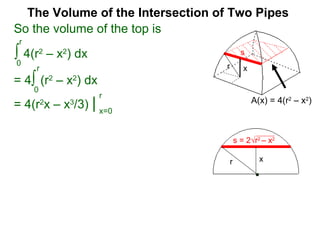

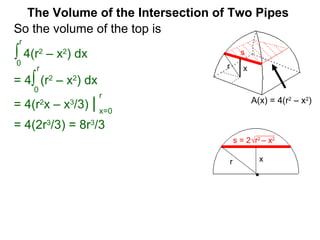

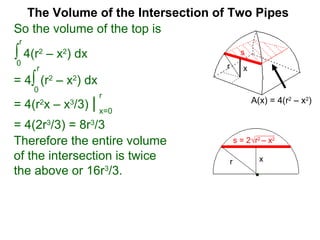

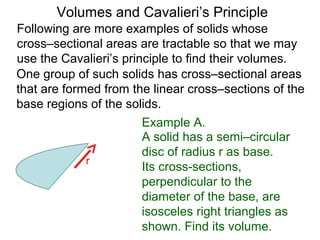

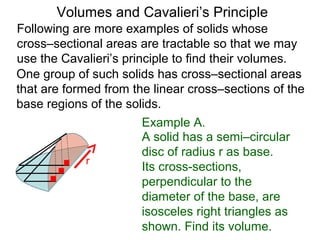

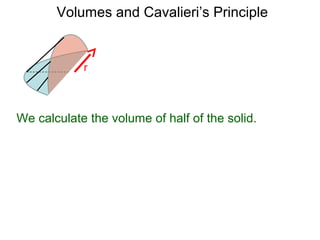

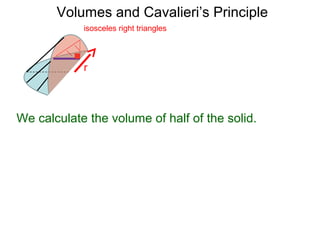

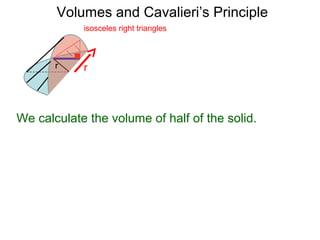

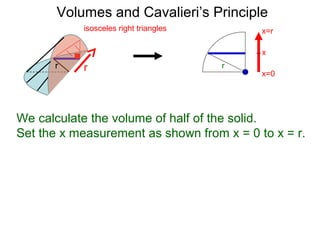

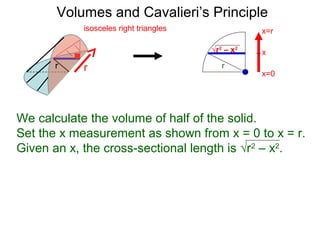

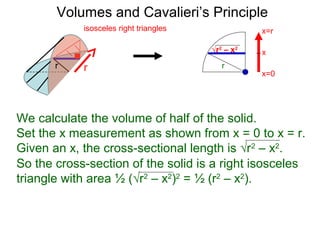

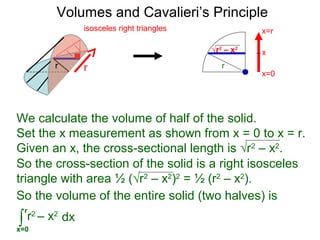

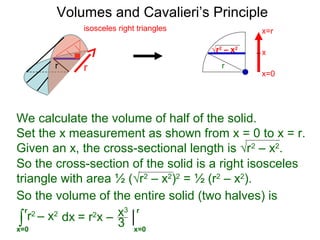

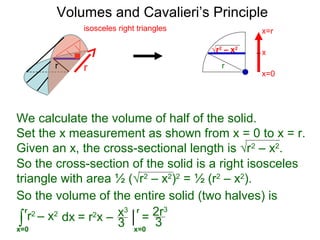

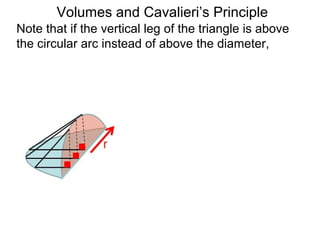

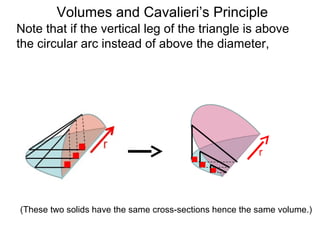

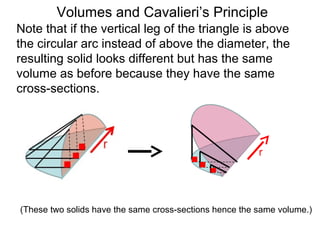

The document discusses Cavalieri's principle, which states that two regions with identical cross-sectional areas have the same volume. It demonstrates this principle by showing how the volume of a circle can be determined by unwinding its concentric rings into a triangle of equal area. The 3D version of the principle is also described, indicating that solids with identical cross-sectional areas have the same volume. Examples of prisms and cones are provided.