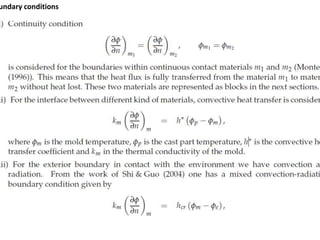

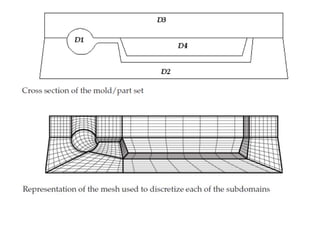

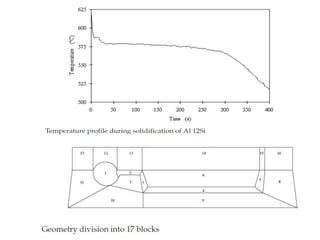

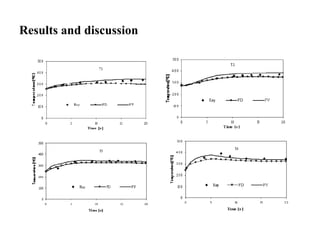

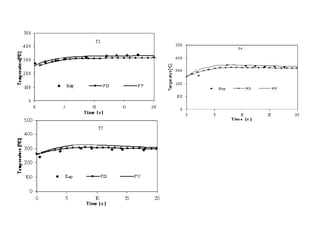

This document presents a numerical study comparing finite difference and finite volume methods for solving the heat transfer equation during solidification in a complex casting geometry. The study uses a multi-block grid with bilinear interpolation and generalized curvilinear coordinates. Results show good agreement between the two discretization methods, with a slight advantage for the finite volume method due to its use of more nodal information. The multi-block grid approach reduces computational time and allows complex geometries to be accurately modeled while overcoming issues at block interfaces.

![Matrix Form

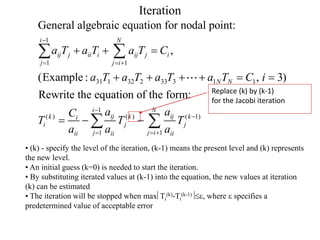

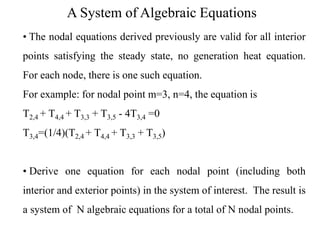

The system of equations:

a11T1 a12T2 a1N TN C1

a21T1 a22T2

a2 N TN C2

a N 1T1 a N 2T2

a NN TN CN

A total of N algebraic equations for the N nodal points and the system can be

expressed as a matrix formulation: [A][T]=[C]

a11 a12

a

a22

21

where A=

aN 1 aN 2

a1N

T1

C1

T

C

a2 N

, T 2 ,C 2

aNN

TN

C N ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/numericalmethodsfor2-dheattransfer-140309114702-phpapp02/85/Numerical-methods-for-2-d-heat-transfer-13-320.jpg)

![Numerical Solutions

Matrix form: [A][T]=[C].

From linear algebra: [A]-1[A][T]=[A]-1[C], [T]=[A]-1[C]

where [A]-1 is the inverse of matrix [A]. [T] is the solution vector.

• Matrix inversion requires cumbersome numerical computations and is not efficient if

the order of the matrix is high (>10).

• For high order matrix, iterative methods are usually more efficient. The famous

Jacobi & Gauss-Seidel iteration methods will be introduced in the following.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/numericalmethodsfor2-dheattransfer-140309114702-phpapp02/85/Numerical-methods-for-2-d-heat-transfer-14-320.jpg)