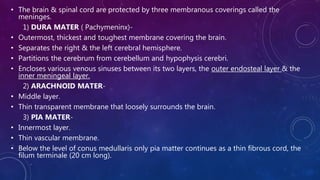

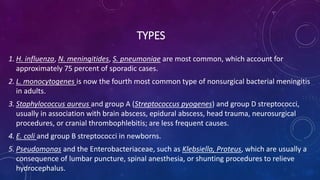

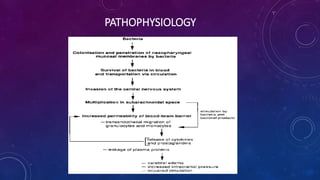

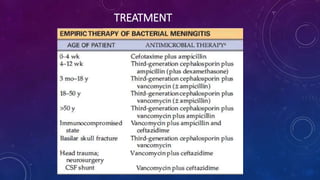

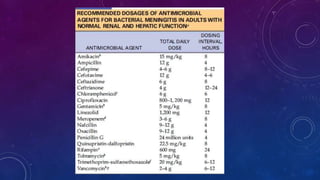

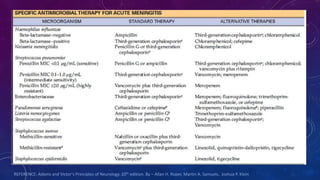

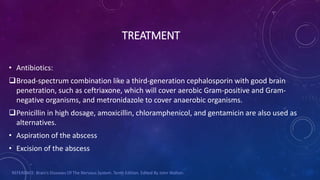

This document discusses pyogenic meningitis (acute bacterial meningitis). It begins by defining pyogenic infections and describing the anatomy of the meninges. It then covers the epidemiology, causes, clinical features, diagnostic process, treatment, and potential sequelae of bacterial meningitis. Key points include that the most common causes are pneumococcus, meningococcus, and H. influenzae. Clinical features include headache, fever, neck stiffness, and signs of meningeal irritation. Diagnosis involves CSF analysis showing pleocytosis and low glucose. Treatment involves intravenous antibiotics and supportive care. Potential long term effects include deafness, epilepsy, or neurological deficits.