Systematic literature review of supply chain risk management in healthcare management

- 1. A systematic literature review on supply chain risk management: is healthcare management a forsaken research field? Pedro Senna and Augusto Reis CEFET/RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Igor Le~ ao Santos Engenharia de Produlç~ ao, CEFET/RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Ana Claudia Dias and Ormeu Coelho CEFET/RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abstract Purpose – This paper aims to present a systematic literature review (SLR) to investigate how supply chain risk management (SCRM) is applied to the healthcare supply chains and which improvement opportunities are being missed in this segment. Design/methodology/approach – This SLR used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method to answer three research questions: (1) Which are the main gaps concerning healthcare supply chain risk management (HCSCRM)? (2) What is the definition of HCSCRM? and (3) What are the risk management techniques and approaches used in healthcare supply chains? Findings – The authors present a complete summary of the HCSCRM body of research, investigating research strings like clinical engineering and high reliability organizations (HROs) and its relations with HCSCRM; (1) This research revealed the five pillars of HCSCRM; (2) The authors proposed a formal definition for HCSCRM considering all the literature blocks explored and (3) The authors generated a list of risks present in healthcare supply chains resulting from extensive article research. Research limitations/implications – The authors only reviewed international journal articles (published in the English language), excluding conference papers, dissertations and theses, textbooks, book chapters, unpublished articles and notes. In addition, the study did not thoroughly investigate specific countries’ particularities concerning how the healthcare providers are organized. Originality/value – The contribution of this article is threefold: (1) To the best of authors knowledge, there is no other SLR about HCSCRM published in the scientific literature by the time of realization of authors’ work, suggesting that is the first effort to fulfill this research gap; (2) Following the previous contribution, in this work the authors propose a first formal definition for HCSCRM and (3) The authors analyzed concepts such as clinical engineering and HROs to establish the building blocks of HCSCRM. Keywords Supply chain risk management, Clinical engineering, High reliability organizations, Healthcare management, Systematic literature review Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Since supply chain risk management (SCRM) emerged as a concept in the early 2000s, significant studies have been produced in the academic literature. For instance, the work by Norrman and Jansson (2004) defines SCRM and describes a real-case study and respective measures for the identification and mitigation of supply chain risks (SCRs), where SCRs can be defined in simple terms, according to Juttner et al. (2003), as the possibility and effect of a mismatch between supply and demand. Moreover, Sodhi et al. (2012), even eight years after Norrman and Jansson (2004), stated that there is no consensus around the SCRM definition. More recently, Baryannis et al. (2019) stated that there is no universally accepted definition of either risks or SCRM and proposed building a SCRM definition by encompassing identification, evaluation, mitigation and monitoring of risks. Supply chain risk management in healthcare The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1463-5771.htm Received 22 October 2019 Revised 12 October 2020 Accepted 1 November 2020 Benchmarking: An International Journal © Emerald Publishing Limited 1463-5771 DOI 10.1108/BIJ-05-2020-0266

- 2. Despite its nonconsensual definitions, SCRM is consistently being applied by managers to enhance performance metrics. For instance, by using SCRM in a hospital pharmaceutical supply chain case study, Elleuch et al. (2013) obtained improvements in five dimensions: (1) budget consistency, (2) reliability, (3) fluidity of drug circuit, (4) flexibility improvement and (5) bullwhip effect control; where the bullwhip effect, for instance, can be especially harmful in sectors that face the challenge of managing a wide variety of items. Elleuch et al. (2013) applied a holistic method that includes risk identification, risk assessment and risk mitigation, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. And among the most studied segments of application of SCRM are the (1) automotive (Thun et al., 2011; Sharma and Bhat, 2014; Heidari et al., 2018), (2) food industry (Song and Zhuang, 2017) and (3) electronics industry (Rajesh, 2017). Healthcare supply chains are a very unique segment, since its main objective is to save lives instead of profit. Healthcare providers (clinics or hospitals) are the facilities that deal with the patients and trigger demand throughout the healthcare supply chain. Either being public or private, healthcare providers must be cost-effective for two main reasons: (1) private healthcare providers must be profitable in order to guarantee business continuity and keep providing healthcare and (2) public healthcare providers also must be cost-effective to ensure that the taxpayer money is well spent. To manage risks and generate supply chain resilience (SCRes), it is crucial to identify the supply chain main characteristics (Li et al., 2020). Considering the upstream healthcare supply chain, constructs that generate resilience include total quality management (TQM) (Sharma and Modgil, 2020), total productive maintenance (Modgil and Sharma, 2016). Among the constructs that generate resilience to the whole healthcare supply chain, we highlight trust, cooperation, supply chain connectivity, supply chain visibility and information sharing (Dubey et al., 2019). Lately, recent studies are also citing supply chain 4.0 and blockchain as resilience generators (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020; Dubey et al., 2020). Although the healthcare segment is not mentioned by authors of the academic literature as one of the most studied segments of application of SCRM, there are clear benefits of making this association, and thus the research gap approached by this work emerges. On the one hand, up-to-date management techniques, such as SCRM, used in the healthcare segment are getting more relevant nowadays. For instance, medical devices nowadays can be of over 5,000 different types and be used in all aspects of healthcare (for example, tongue depressors and pacemakers), representing a difficult management challenge (Dhillon, 2000) that could be approached using SCRM. In addition to the inherent difficulties of managing medical devices, current global population growth and aging are challenging. They drastically increase the need of investments in the healthcare segment and stimulate the search for up-to-date management techniques capable of handling their consequent complex scenarios, such as SCRM. Thus, from different points of view, an essential gap in the literature is revealed, respective to applying SCRM in the healthcare sector. Moreover, the academic literature presents a significant number of literature review papers, approaching SCRes (Hohenstein et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2015; Kamalahmadi et al., 2016); SCRM strategies (Kilubi, 2016b; Kilubi and Hassis, 2015); bibliometric study in SCRM (Kilubi, 2016a); quantitative techniques in SCRM (Hamdi et al., 2015) and the most recent (Gligor et al., 2019) discusses the differences between SCRes and supply chain agility. However, within the literature consulted, there were not any papers that presented a systematic literature review (SLR) in SCRM applied to healthcare supply chains. In this sense, this paper offers a first effort to fulfill this gap in the academic literature. In addition, we could not locate studies that systematically summarize risk management techniques and approaches applied to healthcare supply chains. Considering this preliminary discussion, three research questions arise: RQ1 – Which are the main gaps concerning healthcare supply chain risk management (HCSCRM)? RQ2 – What is the definition for HCSCRM? RQ3 – What are the risk management techniques and BIJ

- 3. approaches used in healthcare supply chains? Therefore, the objectives of this paper are threefold (respectively to each research question): (1) set a complete picture of HCSCRM research field; (2) formally define SCRM applied to healthcare and (3) identify the relevant studies in the healthcare segment that identify, assess and mitigate SCRs, the techniques and approaches they apply and what they conclude. These research questions address three important gaps that we found in the literature. This paper is composed by 11 sections (including this introductory one). Section 2 offers the theoretical background of this literature review, Section 3 presents the methodology, Section 4 analyzes the main literature gaps, Section 5 discuss a formal definition of HCSCRM, Section 6 shows the complete set of statistics regarding the papers found, Section 7 discuss the findings, Section 8 discusses a future research agenda, Section 9 presents the research limitations, Section 10 discuss the managerial implications and Section 11 closes the paper with the conclusions. 2. Theoretical background The term “supply chain risk management” (SCRM) started to be coined in the early 2000s by authors such as Norrman and Jansson (2004), Juttner (2005), Sorensen (2005), Tang (2006) among others. However, even before the concept became popular, the subject was studied, although not yet formally defined as SCRM. For example, Bowersox et al. (1999) preconized lean launch of products to mitigate the risks of higher inventory levels that a make-to-stock (Push) strategy would generate. Lonsdale (1999) presented a model for mitigating risks associated with outsourcing practices. Zsidisin et al. (2000) presented inbound supply risks such as quality, design, cost, availability, manufacturability, supplier, legal, environmental, health and safety. Hallikas et al. (2002) studied risks concerning a supplier, a buying company and assess risks related to networking. Furthermore, Hallikas et al. (2004) expanded the conceptual analysis brought by Hallikas et al. (2002), presenting methods for risk management in a complex network environment. They also concluded that risk management is an important development target in the studied supplier networks. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that at the time, conceptual basis for establishing the building blocks of the SCRM concept were complete and risks concerning inbound and outbound logistics were studied in a way that already transcended companies’ functional barriers. A new cross functional process-based linking supply chain business processes was needed, and so, the SCRM concept came to fill this gap. Nevertheless, our studies reveal that concerning healthcare supply chains, a significant body of literature would be left off if the search strings included only SCRM and healthcare supply chains. Clinical engineering papers present relevant studies on equipment maintenance and spare parts storage that have an intrinsic link to supply chains and its risks. Papers that study high reliability organizations (HROs) and high reliability networks (HRNs) present significant principles that can be included in a SCRes framework, which is corroborated by Sawyerr and Harrison (2020). Therefore, to build a solid theory concerning HCSCRM, we broadened the scope of the search performed in this work, including these complementary frameworks. 2.1 Supply chain risk management (SCRM) Competition and customer demands are constantly increasing and almost all industries face intense competition and globalization effects on business (Fan et al., 2011). To become more competitive, companies started to look at process integration, which is corroborated by authors such as Von Brocke (2014) and Kannengiesser et al. (2016). The next stage after internal process integration would be to integrate those processes, which flow through more than one company, termed as supply chain integration. Most of the supply chain integration Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 4. studies highlight which are supply chain’s main processes (Croxton et al., 2001), how to model a supply chain (Saen et al., 2016) and key performance indicators (KPI) concerning a supply chain (Coelho et al., 2009; Fang andWeng, 2010; Cai et al., 2009). Researchers such as Croxton et al. (2001), Cooper et al. (1997), Lambert andPohlen (2001) among others, preconize that supply chain management (SCM) is the integration and coordination of key supply chain business processes going through all suppliers and manufacturers, to end-user providing products, services and information for customers and all stakeholders. Tang (2006) defines SCM as the management of all material, information and financial that flows through an organization network that produces and delivers products or services for the costumers. Coordination and collaboration of processes and activities are key crucial features and include functions such as marketing, sales, production, product design, procurement, logistics, finance and information. Lately, with process integration inside and outside companies, the theoretical framework for these subjects was complete and formed the required backbone for the emergence of SCRM. Authors such as Norrman and Jansson (2004), Lavastre et al. (2012), Thun and Hoenig (2011) and Pujawan and Geraldin (2009) show that this subject started to be a relevant field of research throughout the world. A study by Neiger et al. (2009) shows supply chains that are composed by hundreds and sometimes even thousands of companies over several tiers presenting significant risks. Nevertheless, Shenoi et al. (2018) highlight that SCRM must be an integral part of the supply chain. Companies and researchers are increasingly paying more attention to SCRM, which is notably triggered by the frequency and intensity of catastrophes, disasters and crises that are increasing on a global scale (Fan et al., 2011). Juttner (2003), Juttner (2005), Thun and Hoenig (2011) agree that the first stage concerning SCRM analysis is to visualize a supply chain as a set of cross-functional processes, therefore, avoiding local solutions that do not result in supply chain optimum. Rahman (2002), Li et al. (2002) and Croxton et al. (2001) highlight the urge to consider global optimum instead of local optimum. Juttner et al. (2003) affirm that the lack of integration between companies within a SC (Supply Chain) may lead to sub-optimal results. Norrman and Jansson (2004) affirm that the focus of SCRM is to understand, and try to avoid, the devastating effects that disasters and disruptions can have in a supply chain. Juttner (2005) affirms that, usually, companies implement organization level risk management and stressed that there was still little evidence of supply chain-level risk management implementation. Managing risks that comprise the whole supply chain can become an exceedingly difficult task. To make this hard task viable, specialists propose logical steps and phases that, if followed thoroughly, result in a promising way of managing risks. For example, Sinha et al. (2004) identified five steps for mitigating supplier risks: (1) identifying risks, (2) assessing risks, (3) planning and implementing solutions, (4) conducting failure modes and effect analysis and (5) improving continuously. Based on an extensive literature review, Sodhi et al. (2012) summarized four key sub-processes for managing SCR: (1) risk identification, (2) risk assessment, (3) risk mitigation and (4) responsiveness to risk incidents. This stream of research has generated valuable insights into the SCRM process and has offered significant implications for practitioners. 2.2 Supply chain resilience (SCRes) Suppy chains must be resilient to disturbances to achieve competitiveness (Barroso et al., 2010). Juttner et al. (2003) affirm that supply chain disruptions can be financial losses, negative corporate image or bad reputation, eventually accompanied by demand loss, as well as damages in security and health. In this sense, today’s globalized, leaner and just-in-time supply chains are more vulnerable to natural and human-made disasters (Soni and Jain, 2011). Also, to respond to these risk drivers, supply chains should develop strategic response capabilities to assess and mitigate disruptions (Singh and Singh, 2019). BIJ

- 5. If a manager only emphasizes lower costs and higher efficiency, lacking resilience practices, the supply chain system will be more vulnerable (Shuai et al., 2011). Although resilience is increasingly becoming an important subject, there are still not many quantitative studies about it. Ponomarov and Holcomb (2009) define resilience as an adaptive capability of the SC to prepare for unexpected events, respond to disruptions and recover from them maintaining continuity of operations at the desired level of connectedness and control over structure and function. Barroso et al. (2011) and Carvalho et al. (2012) affirm that SCRes is a matter of survival. Additionally, SCRes is concerned with the system’s ability to return to its original state or a new, more desirable one after experiencing a disturbance and avoiding the failure modes (Carvalho and Cruz Machado, 2007). Resilience was later defined by Barroso et al. (2010) as the ability to react to the adverse effects brought by disturbances that occur specific moment to maintain SC’s objectives. Resilience can also be considered a way to overcome SC vulnerability (Peck, 2005) and prevent shifting to undesirable states, the ones where failure modes could occur (Carvalho et al., 2012). Kilubi (2016b) presents eight main strategies to deal with SCRs, which are “visibility and transparency”, “flexibility”, “relationships/partnerships”, “postponement”, “multiple sourcing”, “redundancy”, “collaboration” and “joint planning and coordination”. Some of these strategies are also found in papers that approach SCRes, which is the case of Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016). The authors discuss SCRes principles such as “collaboration”, “redundancy”, “agility”, “SCRM culture” and “SC reengineering”. The similarity of these factors shows the complementarity of both concepts showing that SCRM is a way of creating a solid SCRes. Considering SCRes strategies, Haimes (2006) affirms that resilience strategies can be implemented (1) to recover the desired values of the states of a system that has been disturbed, within an acceptable period and at an acceptable cost and (2) to reduce the effectiveness of the disturbance by changing the level of effectiveness of a potential threat. According to Sheffi (2005), companies can develop the resilience in three general ways: (1) creating redundancies throughout the supply chain; for example, holding extra inventory, maintaining low capacity utilization and contracting with multiple suppliers, (2) increasing supply chain flexibility; for example, with adoption of standardized processes, using concurrent instead of sequential processes, planning to postpone and aligning procurement strategy with supplier relationships, and (3) changing the corporate culture. The concept of resilience is closely related with the capability of a system to return to a stable state after a disruption (Bhamra et al., 2011). Based on the literature, Figure 1 shows a summarizing framework. Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework that summarizes nowadays’ consensus regarding the required steps to manage SCRs. The first step consists in risk identification that can be company or supply chain level. The second step consists in risk assessment, this step mainly means that managers should prioritize which risks they have to deal immediately and which risks are less likely to become undesirable events; the last step consists and mitigate and monitor risks, meaning that managers have to tailor mitigation plans and even actions that will take place if the risk materializes. 2.3 Clinical engineering A Clinical Engineer can be defined as a Biomedical Engineer with broader responsibilities such as financial or budgetary management, service contract management and maintenance tasks in healthcare organizations (Cruz and Guar ın, 2017). Clinical engineers are technology specialists who can help healthcare-related professionals to deal with, use, evaluate, acquire, manage and adequately maintain and secure biomedical equipment (Del Solar et al., 2017). Clinical engineering began in the USA during the 70s, having main task as the management of hospital’s equipment (Calil and Ram ırez, 2000). Clinical engineering is a branch of Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 6. engineering applied to clinical care. The term clinical engineering is used to denote engineering involved in the hospital setting (van der Putten, 2010). Healthcare technology management presents itself as a crucial tool to support clinical engineers, following the revolutionary changes that healthcare services are delivering (Walker, 2012). Healthcare IT (HIT) systems became a core infrastructural technology in healthcare and have the potential of mitigating patients’ risks. However, this means that a failure in such systems has the potential of leading to patient harm (Hablia et al., 2018). Medical devices are increasingly becoming necessary for diagnosis and disease management; nowadays, medical procedures rely not only on the physician medical but also on the performance of medical devices (Kramer et al., 2012). In this sense, risk-based prioritization methods are used to identify the critical medical devices subject to a rigorous maintenance program (Mahfoud et al., 2016). An important alternative from purchasing the device is Medical Equipment Loan Services (MELS), which exist to improve availability of equipment for both patients and clinical users, managing and reducing clinical risk, reducing equipment diversity, improving equipment management and reducing the overall cost of equipment provision (Keay et al., 2015). The identification and assessment of risks associated with medical equipment is a crucial part of clinical engineering (Iadanza et al., 2019). Risk management frameworks are usually limited to one company; however, Cruz and Haugan (2019) conduct a survey that considers the impacts of maintenance in a supply chain level. Also, efficient equipment maintenance plans play an essential role in healthcare supply chains due to (1) managing less defective equipment mean that managers can save budget that can be spent in training healthcare professionals and keeping safe medicine stock full; (2) a good maintenance plan can unburden the logistic channels reducing emergency deliveries of spare parts (which will also result in money-saving) and (3) healthcare professionals will be less stressed due to equipment failures and will be able to increase the service level offered to the patient. Clinical engineering is essential for the development of maintenance plans, helping to identify equipment-related risks that are even related to budget risks, as they can estimate how many spare parts are needed and whether an expensive equipment can be repaired or have to be replaced. Considering that a piece of repaired equipment avoids its replacement, an efficient clinical engineering department can positively impact supply chain decisions. In this sense, clinical engineering plays a significant role concerning risk management. Supply Chain Resilience Environment Government Terrorism Operations Income Identify Risks 1 3 2 Assess Risks Continuous iterative process Mitigate and Monitore Risks Resilience Metrics Input Process Output Source(s): Authors’ own elaboration Figure 1. Conceptual framework based on the literature BIJ

- 7. 2.4 High reliability organizations HRO can be considered systems that perform their operations in a nearly error-free basis, even when belonging to risky environments (Roberts, 1990). The devastating effects of incidents led companies to the necessity of improving their resilience and reliability (Agwu et al., 2019). HRO scholars study complex types of organizations that, despite operating in environments where errors could lead to catastrophic consequences, seem to maintain high levels of safety performance. Examples of such operating environments are nuclear power plants, air traffic control and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers (Milch andLaumann, 2018; Høyland et al., 2018). These HROs have specific characteristics and practices that enable them to achieve sustained reliable safety performance and demonstrate unique and consistent characteristics, including operational sensitivity and control, situational awareness, hyperacute use of technology and data and actionable process transformation (Milch andLaumann, 2018). In an HRO, safety and quality are organizational priorities, and all workforce members are continuously learning and improving their work (Aboumatar et al., 2017). In the context of HROs, resilience assessment allows organizations to increase their level of awareness of the environment and their ability to react to threats (Gonçalves et al., 2019). The literature on HROs has identified safety concepts and principles for achieving and maintaining safety at an organizational level (Høyland et al., 2018). Table 1 shows HRO safety concepts and principles. Latent errors are defined as events, activities or conditions that deviate from expectations (Ramanujam and Goodman, 2003; Høyland et al., 2018). Høyland et al. (2018) define the “mindfulness” construct as composed by the following: (1) Sensitivity to operations: management and staff comprehend their processes, how they might go wrong and are aware of how the systems are performing; (2) Reluctance to simplify: When failure occurs, HROs refuse simple explanations for the failure; instead, they pursue and understand each failed system; (3) Preoccupation with failure: HROs maintain a constant pursuit of perfection; (4) Deference to expertise: Leaders listen and respond to the insights into the front line, regardless of rank or title. Humans and systems always make mistakes and things will probably go wrong; therefore, organizational resilience in HROs means that companies can quickly identify an adverse event to rapidly contain and mitigate the error. Høyland et al. (2018) define the construct upon the following pillars: (1) robustness , for example, when a team is designed to keep functioning despite suffering stresses and demands; (2) redundancy is any technical or extra human resources that can be used due to demanding tasks/ operations; (3) resourcefulness is an organization’s ability to identify problems, establish priorities and mobilize resources to handle disruptions and achieve goals; (4) rapidity can be seen in an organization capable of achieving various goals in an effective and timely manner. Nevertheless, Milosevic et al. (2018) affirm that previous knowledge is not always enough considering that the dynamism in HROs creates nonroutine problems; in this sense, HRO safety concepts HRO safety principles Latent errors and mindfulness Sensitivity to operations (SO) Reluctance to simplify (RS) Preoccupation with failure (PF) Commitment to resilience (CR) Deference to expertise (DE) Organizational resilience Robustness (Rb) Redundancy (Rd) Resourcefulness (Rs) Rapidity (Rp) Table 1. HRO safety concepts and principles Supply chain risk management in healthcare

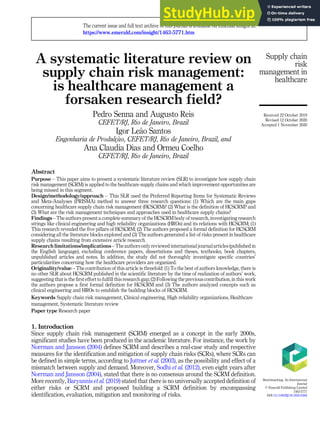

- 8. leadership becomes essential, mostly because of its potential of keeping an operation safe by collective priority (Martinez-C orcoles, 2018). Interorganizational networks are defined as a group of three or more organizations connected in ways that facilitate achievement of a common goal (Berthod et al., 2016). Berthod et al. (2016) define three types of governance that describe how this network will behave: (1) shared governance, implies an absence of central governance structure among participating organizations, (2) lead-organization governance, in which the lead organization implies the coordination of the network by one participant and (3) network administrative organization based governance implies a separate, neutral administrative body, set up to function as a central broker to coordinate the activities of the whole network. Therefore, Berthod et al. (2016) define HRNs as interorganizational networks that must function with dual, uninterrupted attention to both the anticipation and the containment of incidents and peaks in activities. Concerning healthcare organizations, the literature mentions the high reliability health care maturity (HRHCM) model, a model for helping healthcare organizations to achieve high reliability, which incorporates three major domains: leadership, safety culture and robust process improvement (Sullivan et al., 2016). 3. Methodology Our full research methodology is presented in the workflow seen in Figure 2. 3.1 Formulation of research questions In the first step of our methodology, we make sure that the research scope is in adherence to the objectives, and the underlying study questions are defined (Kilubi, 2016a). Furthermore, Light and Pillemer (1984) affirm that a precise focus for research starts to be set with an exact research question. RQ1. Which are the main existent gaps concerning HCSCRM? RQ2. What is the definition for HCSCRM? RQ3. What are the risk management techniques and approaches used in healthcare supply chains? 3.2 Selection of databases In order to search for our research terms, we chose the Scopus database, which is the largest database of peer-reviewed literature. Additionally, we decided the ISI Web of Science, which is not as large as Scopus, but can recover papers from a higher year range than Scopus. Moreover, using Scopus and ISI as search engines allows locating papers of Science Direct, Taylor and Francis, Emerald, Springer and other important bases used by this SLR. 3.3 Definition of search terms Regarding our first research question, we used the following strings of word combinations (STR1): (1) supply chain risk management, (2) SCRM and (3) supply chain resilience. Regarding STR1, the healthcare segment appeared in five studies while we found three studies concerning the pharmaceutical industry. Since the pharmaceutical segment is a component of the HCSC (Healthcare Supply Chain), we considered both categories (pharmaceutical and healthcare) as a single category. In order to construct a broader theory, we searched for healthcare supply chain papers in general, aiming to capture insights into recurrent risk themes, generating a second search using the word combinations (STR2): BIJ

- 9. Formulate research question Select database Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Step 5 Step 6 Results section Define search terms Records identified through database searching (Scopus + WOS, n = 911) Records after duplicates removed (n = 641) Records screened (n = 641) Full text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 297) Screening Identification Eligibility Included Methodology section – Article selection process Studies included in this SLR (n = 8) Further exclusion due to not fitting in Healthcare research Records excluded due to not fitting the research scope (n = 344) Additional records identified through other sources (n = 0) Records identified through database searching (Scopus + WOS, n = 427) Records after duplicates removed (n = 303) Records screened (n = 303) Full text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 114) Studies included in this SLR (n = 114) Records excluded due to not fitting the research scope (n = 189) Additional records identified through other sources (n = 0) Records identified through database searching (Scopus + WOS, n = 307) Records after duplicates removed (n = 272) Records screened (n = 272) Full text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 119) Studies included in this SLR (n = 119) Records excluded due to not fitting the research scope (n = 153) Additional records identified through other sources (n = 0) Hohenstein et al. (2015); Kamalahmadi et al. (2016); Kilubi (2016b) Hohenstein et al. (2015); Kamalahmadi et al. (2016); Kilubi (2016b); Kilubi (2016a); Kilubi and Hassis (2015); Hamdi et al. (2015); Ho et al. (2015) Hohenstein et al. (2015); Kamalahmadi et al. (2016); Kilubi (2016b); Kilubi (2016a); Kilubi and Hassis (2015); Hamdi et al. (2015) Hohenstein et al. (2015); Kamalahmadi et al. (2016); Kilubi (2016b); Kilubi (2016a); Kilubi and Hassis (2015); Ho et al. (2015) Kamalahmadi et al. (2016); Kilubi (2016b); Hamdi et al. (2015); Ho et al. (2015) Analyze Papers Reporting and using results Source(s): Authors’ own elaboration Figure 2. Research methodology workflow Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 10. (1) healthcare procurement, (2) healthcare supply chain risk, (3) healthcare supply chain and (4) healthcare warehouse. To complete the body of research strings, we included concepts that are often neglected by SCRM researchers (STR3): (1) clinical engineering, (2) resilient engineering and (3) HROs. 3.4 Article selection process The article selection process was based in Patel and Desai (2018), Marques et al. (2019) and the PRISMA protocol created by Moher et al. (2009). PRISMA is an acronym for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses method. This protocol is mostly used in healthcare SLR and meta-analysis; nevertheless, it is also used in industrial engineering segment, see for example Muhs et al. (2018). In the filtering stage, we followed the criteria of Patel and Desai (2018) and Marques et al. (2019): (1) we excluded conference papers, short notes, book chapters and editorial notes and (2) we considered only papers written in English language. In addition, a “.bib” file was generated for each search and analyzed in R language where a single database file was generated with duplicates removed to generate a bibliometric analysis. The complete set of statistics and analysis performed in our work is depicted in the following sections. 4. Which are the main gaps concerning healthcare supply chain risk management? In this section, we present the main findings of SCRM and SCRes related to healthcare. Our initial hypothesis considered that studies on healthcare supply chains were not as much as studies on supply chains in general. In this sense, we conducted an initial search considering strings such as “supply chain risk management” and “supply chain resilience”, as well as the acronyms. Therefore, the search using STR1 and its postprocessing resulted in eight papers. The searches using STR2 and STR3 returned 114 and 119 studies, respectively. Since the number of papers returned varies, our approach also changes accordingly. We discuss each of the eight articles found by the search using STR1 and its postprocessing and detail their main contributions and research gaps, whereas in searches using STR2 and STR3, we summarize the main findings. Table 2 shows the eight papers composing the result of the search using STR1 and its postprocessing. Analysis of Figure 3 shows that healthcare and pharmaceutical papers are the third category in terms of published articles considering all segments. Pharmaceutical and healthcare categories present numerous particularities. Nevertheless, they embody the healthcare supply chain construct. Healthcare studies are more clinical-related papers, while pharmaceutical articles deal with OEM (original equipment manufacturer) related issues. Considering that the pharmaceutical category includes one review and one conceptual framework, we can affirm that literature in this segment lacks empirical studies. Jaberidoost Authors Segment Approach Jaberidoost et al. (2013) Pharmaceutical Literature review Jaberidoost et al. (2015) Pharmaceutical AHP Elleuch et al. (2013) Pharmaceutical FMEA, AHP and Doe Aguas et al. (2013) Healthcare System dynamics Zepeda et al. (2016) Healthcare Econometric methods Riley et al. (2016) Healthcare SEM Jafarnejad et al. (2019) Healthcare Fuzzy and system dynamics Haeri et al. (2020) Healthcare Fuzzy Table 2. Detailing of healthcare and pharmaceutical papers BIJ

- 11. et al. (2013) present a literature review focused on a pharmaceutical manufacturer (OEM) where they are classified into five major risk categories: (1) supply and suppliers issues, (2) organization and strategies issues, (3) financial, (4) logistic, (5) market, (6) political and (7) regulatory. The authors conclude affirming that risk identification and mitigation can optimize SCM as well as improve performance measures such as accessibility, quality and affordability. Jaberidoost et al. (2015) is an empirical paper in which the authors identify risks presented by the literature and then assess those risks interviewing professionals. They extended the risk list present in Jaberidoost et al. (2013) and came up with 86 risks identified. The main conclusion of the paper is that the main pharmaceutical SCRs are regulation-related ones. Elleuch et al. (2013) propose a framework for systematic approaching SCRM including (1) FMECA (Failure Modes, Effects and Criticality Analysis), (2) Design of an experiment to design risks mitigation and action scenarios, (3) Discrete event simulation to assess risks mitigation action scenario, (4) AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) to evaluate risk management scenarios and (5) desirability function approach to minimize the risk. The authors validate their methodology in a pharmaceutical supply chain case. Although presenting an empirical robust method, the study does not go into an in-depth discussion concerning risk identification. Aguas et al. (2013) conducted a supply chain risk analysis applying system dynamics to the Colombian healthcare sector, more specifically, in the oncology healthcare SC. Among the main risks detected by the authors are delays in delivering times and lack of medication to treat all the patients. Figure 3. Absolute number and cumulative percentage of SCRM papers per segment Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 12. Zepeda et al. (2016) focus on hospital inventory costs and investigate the potential mitigating effects of affiliation with multi-hospital systems and came up with inventory- related hypothesis and use econometric methods to test them. As main conclusions, the authors concluded that there is a relationship between demand uncertainty for a hospital’s clinical requirements and a hospital’s inventory costs. The assumption that demand uncertainty for clinical requirements moderates the relationship between system affiliation and a hospital’s inventory costs was not supported. Riley et al. (2016) conduct a survey where they test assumptions such as (1) Do internal hospital integration result in an improved warning and recovery capabilities? (2) Do improved information-sharing competences result in an improved warning and recovery capabilities? (3) Do enhanced training competences result in an improved warning and recovery capabilities? and (4) Do improved warning and recovery capabilities result in improved performance? The authors found evidence suggesting that internal integration could be used to enhance organizations’ SCRM capabilities. Jafarnejad et al. (2019) investigate the key factors affecting the resilience of the supply chain of medical equipment. The authors apply fuzzy to determine the key factors and system dynamics to analyze the relationship between them. The methodology can be applied to other healthcare chains to compare the results. Haeri et al. (2020) study a blood supply chain, which is very complex due to donation uncertainties. The authors use data envelopment analysis to measure the efficiency of the supply chain. Since disruptions in the bloodstock can cause a collapse in the network, different measures of resilience as optimization tools were considered. The literature on risks presents a wide range of techniques. Still, they have been scarcely adapted to the needs of SCM and even more scarcely considering healthcare supply chains (Khan and Burnes, 2007). In the last five years, SCRM has been largely studied with many different approaches and applications. However, when research is conducted with the specific objective of finding SCRM applied to healthcare, namely HCSCRM, only a few papers were found. These few papers can be sorted into two types, papers that explicitly analyze SCRM applied to HC (Healthcare) organizations and articles which eventually discuss solutions to problems that consist of significant risks and may cause service rupture. Concerning papers that approach HCSCRM, Vanvactor (2011) highlights the importance of disaster mitigation to prevent SC breakdown and draws attention to crisis mitigation concepts. Thus, based on Vanvactor (2011), we can define healthcare SC resilience as a capability to be responsive to disasters, as well as SC breakdowns still being able to provide a full continuum of services to all patients arriving at a facility for care. A study seen in Zepeda et al. (2016) highlights the risks concerning mismatch between supply and demand and discusses risks of higher inventory costs. Other papers discuss issues that may indirectly contribute to measure and mitigate risks, as is the case in Eiro and Torres-Junior (2015), which discuss cases of healthcare organizations that implemented TQM and Lean through the implementation of tools like value stream map (VSM) and failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA). Such tools, techniques and concepts are process improvers that have been used in the last decades to mitigate intra organizational undesired effects. Nevertheless, such local improvements can also generate supply chain-level benefits; for example, a supply chain reverse flow may be started because of quality problems or lack of efficiency (which is often improved by the adoption of Lean practices). Nevertheless, papers are mentioning healthcare SCRs , although not directly. For example, Rakovska and Stratieva (2017) mention that pharmaceuticals and medical devices are of particular interest because they must meet specific requirements of several clinical departments and therefore, present significant risks of stock out. Mandal and Jha (2017) and Niemsakul et al. (2018) analyze the role of collaboration considering hospital–supplier, which helps mitigate risks related to demand changes. Syahrir et al. (2015) highlight how a BIJ

- 13. healthcare supply chain plays a major role in natural disasters mitigation. Mandal (2017) uses SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) to empirically confirm the hypothesis that develop, group and rational cultures contributes positively to healthcare supply chain resilience (HC SCRes) while hierarchical culture inhibits it. Still limited systematic research has been conducted to identify practices and strategies for improving hospital supply chain performance (Zepeda et al., 2016). Lack of proper studies concerning risks in healthcare are specifically hazardous. According to Riley et al. (2016), a shortage of supply or unanticipated demand spike for hospitals can lead to catastrophic consequences beyond low in stock metrics. When a hospital experiences an unexpected demand spike or supply shortage, supply managers must have the means to alter and/or reconfigure the supply chain (Riley et al., 2016). The authors conclude that by developing SCRM capabilities, organizations can better address an array of SCRs. 5. Defining healthcare supply chain risk management Up to this point, our paper showed that SCRM applied to healthcare supply chains lacks empirical studies. One reason is the lack of a formal definition of SCRM in healthcare. Is it only a straightforward merge of the two concepts or does it have particularities that require further definition to be effectively studied? Fan and Stevenson (2018) divide SCRM definitions into three categories: (1) SCRM process – definitions that identify the main stages that companies must go through to manage risks in a supply chain level; (2) Pathway to SCRM – these are the definitions that highlight the importance of implementing SCRM strategies and (3) Objective of SCRM – many definitions set establish the ultimate goal of SCRM that can be insure cash-flow management, cost saving and guarantee business continuity. Nevertheless, healthcare management must include other elements, considering they form a SC that should care more about lifesaving than profit itself. Table 3 shows the main definition elements. Therefore, the definition of HCSCRM is defined as follows: “The process of identifying, assessing, mitigating and monitoring SCRs aiming to provide the best quality of care through SC processes integration, with sustainable profit avoiding supply shortage, valuing HC and clinical engineering professionals, having in consideration that local actions may generate hazards to all HCSC generating SCREs and HRHCN”. Definition element Text Reference SCRM stages The process of identifying, assessing, mitigating and monitoring SCRs Fan and stevenson (2018), Nabelsi (2011) Objectives Aiming to provide the best quality of care Kokilam et al. (2016), Mishra et al. (2018) Pathway to SCRM Through SC processes integration, with sustainable profit avoiding supply shortage and HC professional’s unhappiness Borelli et al. (2015), Abukhousa et al. (2014), Mustaffa and Potter (2009), Breen and Crawford (2005), Iannone et al. (2014), Balc azar-Camacho et al. (2016), Mishra et al. (2018) Generating reliability Having in consideration that local actions may generate hazards to all HCSC Authors Human resources Valuing HC professionals as well as clinic engineers Chen et al. (2018) Generating resilience In that way generating SCREs and high reliability healthcare network (HRHCN) Authors Table 3. Construction of the HCSCRM definition Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 14. The proposed definition sought to contemplate the main building blocks responsible to mitigate SCRs and generate SCRes. In addition, the definition comprises often-neglected concepts such as clinical engineering and features that are essential in building a high reliability organization that is part of a high reliability network. Supply chains that are often studied (such as automotive and food) refer to businesses where there is a well-defined product, with well-defined outcomes and KPIs and can be comprised by SCRM definitions that are already fairly discussed in the literature. Nevertheless, healthcare supply chains have particularities: (1) their main objective is to save lives providing the best quality of care and (2) it is a SC that still needs revenues in order to survive. Considering this idiosyncratic SC and the lack of HCSCRM studies, it is essential to supplement the theory with clinical engineering and HRN concepts. Therefore, HCSCRM is constructed by SCRM, SCRes (concepts within SCM domain) and supplemented by clinical engineering and HRO. Figure 4 represents the proposed framework. 6. Techniques and approaches in healthcare supply chains This section summarizes the main approaches and techniques found in the literature. Due to its particularities, the strings are analyzed separately. 6.1 STR2 analysis Concerning the papers found by STR2 search, Table 4 summarizes the main approaches to obtain healthcare supply chain improvements. Papers that conduct survey analysis (either qualitative or quantitative) are about 24.6% of the studies, and conceptual analysis represent 13.2% of the studies. Literature review, survey and conceptual papers totalize 46.5% of papers, meaning that literature could benefit from more applied studies. Table 5 shows some more interesting statistics regarding the analysis. Almost all the papers present some sort of identification technique or at least they discuss an already known problem. In terms of assessment techniques (techniques that allow to thoroughly know the risks magnitude), we notice a considerable fall, which shows considerable opportunities regarding risk assessment. Considering mitigation actions to either minimize risk probability or diminish the risk effects, we found out that only 36.8% carry on such actions. In terms of continuous monitoring (once the risks are identified, Healthcare Supply Chain Risk Management Supply Chain Risk Management Supply Chain Resilience Clinical Engineering High Realiability Organizations Supply Chain Management Figure 4. Healthcare supply chain risk management constructs BIJ

- 15. assessed and mitigated) is where we notice the greater gap with only 9.6% of the papers presenting KPI able to control this process systematically. Table 6 shows a similar analysis about healthcare supply chain tiers. From Table 6, we infer that HCSC studies focus more on the internal hospital chain, highlighting the central storeroom. Considering the upstream SC, we perceive how they are considerably less studied. Approach Quantity Survey analysis 28 Conceptual analysis 15 Literature review 10 Statistical analysis 9 Simulation 8 DEA 5 Data warehouse 4 Mathematical programming 4 Neural networks 3 Literature review and survey analysis 2 Procurement improving 2 AHP 2 Mathematical model 2 Interviews 2 Game theory 2 Healthcare process reengineering 1 Accounting analysis 1 Algorithm development 1 Collaborative practices implementation 1 Survey analysis and simulation 1 CPFR and AHP 1 Risk-sharing approach implementation 1 FMEA and IDEF0 1 Pareto analysis 1 Inventory management 1 ABC classification 1 VMI implementation 1 Problem-solving framework 1 Performance management 1 Resource-based view 1 DEMATEL 1 Identification Assessment Mitigation Monitoring 112 80 42 11 98.2% 70.2% 36.8% 9.6% Vendors Manufacturers Distributors Hospital central store room Nursing units Points of care 46 49 63 83 58 65 40.4% 43.0% 55.3% 72.8% 50.9% 57.0% Table 4. Healthcare supply chain approaches Table 5. SCRM stages approached Table 6. Supply chain tiers approached Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 16. 6.2 Analysis of STR3 The STR3 returned two main concepts, which provide a relevant contribution to the study; clinical engineering (82 papers) and HRO (37 articles), which are separately analyzed. 6.2.1 Clinical engineering findings. The clinical engineering area of study has the potential of complementing the SCRM theory because the studies provide local solutions that may positively impact the whole supply chain. Figure 4 shows that CE (Clinical Engineering) papers give insights on subjects, which are also in the SCRM context. Concerning risk management applied in healthcare supply chains, only a few papers can be found. Even in these few papers a whole body of literature constituted by clinical engineering is left out of the analysis. To define healthcare SCRM, it is essential to do analyze this area of knowledge to close these gaps. Clinical engineering papers present relevant medical studies which include (1) medical devices maintenance management (Wang et al., 2013), (2) clinical engineering systems (Ibey et al., 2015), (3) quality management (Koustenis and To, 2012) and (4) risks (Chen et al., 2018; Mahfoud et al., 2016). Such studies present analyzes and solve problems that are often supply chain related, therefore presenting real possibilities of completing the SCRM theory. Figure 5 shows statistics regarding (CE) STR3 search. Clinical engineering studies excel in areas such as maintenance management, quality management, medical equipment management and support to systems implementation. These subjects are the backbone of CE and the speciality of clinical engineers; nevertheless, clinical engineers are increasingly required to perform management tasks. The quantitative analysis of clinical engineering studies is found in Table 7. Figure 5. Absolute number and cumulative percentage of clinical engineering sub-areas of study BIJ

- 17. In terms of approaches, STR3 has 73.1% of practical/applied papers, which shows considerable improvement comparing to STR2 paper types. Nevertheless, a qualitative analysis based on the STR3 paper reading shows that there is not much formal reference to supply chain issues, even though there are very recurring problems such as medical device defects, order delays and incomplete orders, which are classic supply chain problems. Figure 6 shows analysis of STR3 approaches. 6.2.2 High reliability principles applied to HC. Papers including HRO concepts include many different segments. Table 8 shows the quantitative analysis on HRO. Figure 7 shows the HRO approaches. 6.2.3 HCSC risks identified. The SCRM literature already has a significant amount of studies identifying risks (Juttner et al., 2003; Norrman and Jansson, 2004; Barroso et al., 2010; Petit et al., 2013). Based on risk categories created by Juttner et al. (2003) and Petit et al. (2013), we summarized the HCSC list of risks (Table 9). 7. Discussion This paper aimed to conduct a systematic literature review to answer three research questions: RQ1– Which are the main existent gaps concerning HCSCRM? RQ2 – What is the definition for HCSCRM? and RQ3 – What are the risk management techniques and approaches used in healthcare supply chains? In section 4, we answered the RQ1 by discussing the papers we found and concluding that the SCRM literature is lacking HCSCRM studies. In section 5, we addressed the RQ2, proposing a complete definition of HCSCRM. In section 6, we answered RQ3, analyzing the tools and techniques that scholars are using to approach SCRM. Table 9 is a product of a systematic literature review where the risks were Approach Quantity Statistical analysis 23 Conceptual analysis 22 Process improvement 7 Cost analysis 3 Risk analysis 3 Multiple linear regression 2 Qualitative interviews 2 Survey 2 AHP 1 Application development 1 Behavioral quality assurance 1 Data mining 1 Decision support system 1 Fuzzy 1 Interviews 1 Literature review 1 Multi-criteria analysis 1 Multi-criteria decision-making 1 Multivariate regression 1 QFD 1 Risk classification 1 Simulation 1 Web-based platform 1 FMECA 1 Resource-based view 1 Computerized maintenance management system 1 Table 7. Quantitative analysis of clinical engineering studies Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 18. identified. There was a detailed work of analyzing the risks to conclude which categories they should be in and which risks that appear with different names could mean the same risk. Approaches Quantity Conceptual analysis 10 Risk management 6 HRO principles 5 Survey 3 Role framework for workforce 1 Relational aspect 1 Quality reference model 1 Literature review 1 Lean/six sigma HRO 1 Interviews 1 High reliability networks 1 High reliability health care maturity model 1 High reliability culture 1 Adoption of aviation practices 1 Confirmatory factorial analysis 1 Benchmarking 1 FMECA 1 Figure 6. Absolute number and cumulative percentage of clinical engineering techniques Table 8. HRO approaches BIJ

- 19. Table 9 can also be detailed to answer to specific investigation in further studies. Concerning the five constructs presented in Figure 6, there are five pillars. SCM is a well-consolidated concept that was tailored by professionals and scholars in the last three decades and is the basis for all SC analysis. SCRM and SCRes are two concepts that have been studied and defined in the last 15 years; therefore, there is still some divergence in the literature, although many convergences. First, it is essential to highlight that SCRM involves an understanding that a SC is a set of processes and local risks that can generate troubles for the entire SC; therefore, risk identification, assessment, mitigation and monitoring are the essential stages of obtaining SCRM. SCRes is the capability that a SC has to endure crisis and arise at the same level of performance or even better, so it is a set of capabilities that should be forged in any SC. Clinical engineering plays a major role in HCSC. Clinical engineers have great potential to give consultancy and generate savings in the HCSC. CE is a SC tier that is responsible for approving a 100,000 US$ equipment or diagnose that the same equipment can be repaired for half the cost; therefore, it is a SC link that is also responsible to bridge the gap between management and giving patients better quality of care. HRO and HRN provide principles that converge to the generation of SCRes and the generation of resilience in HCSC. Figure 7. Absolute number and cumulative percentage of HRO approaches percentages Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 20. Risk category Risks Reference Environmental Disasters Vanvactor (2016) Environmental risks Chiarini et al. (2017), Viani et al. (2016) Flood Farley et al. (2017) Government risks Chandra (2008) Hazardous wastes risks Viani et al. (2016) Legal risks Askfors and Fornstedt (2018) Sustainability risks Gelderman et al. (2017) Deliberate threats Corruption Cavalieri et al. (2017) External pressures Purchasing cost higher than expected Lin and Ho (2014) Insufficient e-government services Katsaliaki and Mustafee (2010) Lack of health service supply chain design Helo (2016) Lack of macro-ergonomics conditions in HCSC Azadeh et al. (2016) Procurement risks Meehan et al. (2017) Technology risks Mandal (2017) Organizational/ resource limits Blood wastage Arvan et al. (2015) Capability Meehan et al. (2017) Costs Campling et al. (2017), Mudyarabikwa et al. (2017) Culture risks Mandal (2017), Campling et al. (2017), Mandal (2017), Mandal (2017), Mandal (2017) Drug recalls management Bevilacqua et al. (2015) Excess of packaging material Kumar et al. (2008) financial risks Mudyarabikwa et al. (2017) No comprehensive e-procurement system Lin and Ho (2014) Institutional pressures (coercive, mimetic and normative and endogenous pressures) Bhakoo and Choi (2013) Internal conflicts Ancarani et al. (2016) IT risks Afshan and Sindhuja (2015), Borelli et al. (2015) Lack of efficiency Mudyarabikwa et al. (2017) Lack of executive support McKone-Sweet et al. (2005) Lack of expertise McKone-Sweet et al. (2005), Campling et al. (2017) Lack of product rotation Hall (2016) Lacking provision of dressings to nurses Jenkins (2014) Long waiting times Kumar et al. (2009) Misalignment of priorities Ancarani et al. (2016) Prescription errors Awofisayo et al. (2011) Time waste (from nonvalue added activities) Bendavid et al. (2010) Turnover Ancarani et al. (2016) Sensitivity Expired drug management Bevilacqua et al. (2015) Huge variety of drugs Lin and Ho (2014) Management of product expiration date Kastanioti et al. (2013) Performance measurement risks McKone-Sweet et al. (2005), Nabelsi (2011) (continued) Table 9. HCSC risks identified BIJ

- 21. 8. Conclusion 8.1 Managerial implications Healthcare supply chain managers daily deal with the dilemma of mitigating risks costs versus costs and losses caused by the risks. Concerning healthcare, managers must consider that minimizing costs could not result in lesser care for the patients. In this sense, it would be a natural consequence to invest in control towers that can manage all KPIs and data science applications to be always and automatically identifying, assessing, mitigating and monitoring risks. 8.2 Research limitations While this research carefully examined the extensive SCRM literature, it has limitations. As the main limitations, we cite the fact that we reviewed international journal articles (published in the English language), excluding conference papers, master and doctoral dissertations, textbooks, book chapters, unpublished articles and notes. In terms of selection criteria, Kilubi and Haasis (2015), Kamalahmadi and Parast (2016) used ABS (associationofbusinessschools.org) ranking and limited to journals with 3 or 4 grade. Kilubi (2016) included in her paper peer-reviewed journals with a VHB ranking (vhb. online.org/startseite) of Aþ, A, B or C, which were defined as one of the criteria. Nevertheless, Risk category Risks Reference Network Communication risks Askfors and Fornstedt (2018), Grudinschi et al. (2014) Credibility risks Kumar et al. (2005), Kokilam et al. (2016), Afshan and Sindhuja (2015), Meehan et al. (2017) Data management risks Hall (2016), Jannot et al. (2017), McKone-Sweet et al. (2005) No integrated and unified information system between hospital and its suppliers Lin and Ho (2014) No information sharing between hospital and its suppliers Lin and Ho (2014) No collaboration Lin and Ho (2014) Information risks Hall (2016), Jannot et al. (2017), Chandra (2008), Iannone et al. (2014), Kumar et al. (2009) Picking risks Piccinini et al. (2013) Relationship risks McKone-Sweet et al. (2005), Grudinschi et al. (2014) Warehouse management risks Spisak et al. (2016), Meehan et al. (2017) Supplier/customer disruptions Demand risk Balc azar-Camacho et al. (2016), Kokilam et al. (2016) Distribution risks Kumar et al. (2005), Afshan and Sindhuja (2015), Spisak et al. (2016), Arvan et al. (2015), Mustaffa and Porter (2009) Hospital–supplier integration– mitigators Afshan and Sindhuja (2015) Quality risks Kastanioti et al. (2013), Kumar et al. (2005), Mudyarabikwa et al. (2017) Supply risks Campling et al. (2017), Chandra (2008), Spisak et al. (2016), Kastanioti et al. (2013), Iannone et al. (2014), Chandra (2008) Table 9. Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 22. this paper did not impose any journal restriction on our list to ensure that all relevant studies were captured, which is consonant with the vision of Ho et al. (2015). Additionally, this paper chose not to use this ranking because a broader scope was needed, and since the SCRM papers related to healthcare are only few, adding more constraints could reduce to none the amount of papers related to healthcare. In addition, the study did not thoroughly investigate specific countries’ particularities concerning how the healthcare providers are organized (for example, specificities of countries that have public and private healthcare organizations). In this sense, there could be idiosyncrasies that were not considered by this study. 8.3 Final remarks Thispaper had the objective of conducting a SLR to investigate SCRM applied tothe healthcare segment via three research questions: (1) Which are the main existent gaps concerning SCRM? (2) What is the definition for HCSCRM? and (3) Which approaches are being used to identify, assess and mitigate healthcare supply chain risks? As the main conclusion, we highlight the lack of empirical studies concerning this stream of research; therefore, we addressed the three research questionsgenerating four innovativeproducts:(1) Webroughta completesummary of this bodyof research, investigating research strings likeclinical engineering and HRO and their relations with HCSCRM; (2) This broader search revealed the five pillars of HCSCRM, summarized by Figure 6; (3) Considering the whole literature investigated, we proposed a formal definition for HCSCRM considering all the literature blocks investigated and (4) We generated a list of risks resulting from an extensive article research. 8.4 Future research agenda As a recommendation of future research agenda, we propose that the framework presented in this paper be further investigated and empirically tested in a real-case study. Researchers should conduct qualitative and quantitative interviews to validate all the information presented by this paper. Applying the framework of identifying, assessing, mitigating and monitoring could include a whole automation of this process. The paper showed that there are only few studies of HCSCRM; in this sense, there is a whole stream of research to be explored in this segment. References Aboumatar, H.J., Weaver, S.J., Rees, D., Rosen, M.A., Sawyer, M.D. and Pronovost, B.J. (2017), “Towards high-reliability organising in healthcare: a strategy for building organisational capacity”, BMJ Quality and Safety, Vol. 26 No. 8, pp. 663-670. Abukhousa, E., Al-Jaroodi, J., Lazarova-Molnar, S. and Mohamed, N. (2014), “Simulation and modeling efforts to support decision making in healthcare supply chain management”, The Scientific World Journal, Vol. 2014, 354246, doi: 10.1155/2014/354246. Afshan, N. and Sindhuja, J. (2015), “Supply chain integration in healthcare industry in India: challenges and opportunities”, Global Business Advancement, Vol. 8 No. 4, doi: 10.1504/JGBA. 2015.074029. Agwu, A.E., Labib, A.W. and Hadleigh-Dunn, S. (2019), “Disaster prevention through a harmonized framework for high reliability organisations”, Safety Science, Vol. 111, pp. 298-312. Aguas, J.P.Z., Adarme, W.A. and Serna, M.D.A. (2013), “Supply risk analysis: applying system dynamics to the Colombian healthcare sector”, Ingenier ıa e Investigaci on, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 1-11. Ancarani, A., Di Mauro, C., Gitto, S., Mancuso, P. and Ayach, A. (2016), “Technology acquisition and efficiency in Dubai hospitals”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 113, pp. 475-485, doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.07.010. BIJ

- 23. Arvan, M., Tavakkoli-Moghaddama, R. and Abdollahi, M. (2015), “Designing a bi-objective, multi- product supply chain network for blood supply”, Uncertain Supply Chain Management, Vol. 3, pp. 57-68, doi: 10.5267/j.uscm.2014.8.004. Askfors, Y. and Fornstedt, H. (2018), “The clash of managerial and professional logics in public procurement: implications for innovation in the health-care sector”, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 78-90. Awofisayo, S.O., Jimmy, U.A. and Eyen, N.O. (2011), “Procurement of prescription only medicine (pom); sources, pattern and appropriateness”, Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science, Vol. 1 No. 7, pp. 46-49. Azadeh, A., Haghighi, S.M., Gaeini, Z. and Shabanpour, N. (2016), “Optimization of healthcare supply chain in context of macro ergonomics factors by a unique mathematical programming approach”, Applied Ergonomics, Vol. 55, pp. 46-55. Balc azar-Camacho, D.A., L opez-Bello, C.A. and Adarme-Jaimes, W. (2016), “Strategic guidelines for supply chain coordination in healthcare and a mathematical model as a proposed mechanism for the measurement of coordination effects”, Dyna, Vol. 83 No. 197, pp. 203-211, doi: 10.15446/ dyna.v83n197.55596. Barroso, A.P., Machado, V.H. and Machado, V.C. (2010), “The resilience paradigm in the supply chain management: a case study”, Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management. Barroso, A.P., Machado, V.H. and Machado, V.C. (2011), “Supply chain resilience using the mapping approach”, InTech, Vol. 161, pp. 161-184. Baryannis, G., Validi, S., Dani, S. and Antoniou, G. (2019), “Supply chain risk management and artificial intelligence: state of the art and future research directions”, International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 57 No. 7, pp. 2179-2202. Bendavid, Y., Boeck, H. and Philippe, R. (2010), “Redesigning the replenishment process of medical supplies in hospitals with RFID”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 16 No. 6, pp. 991-1013, doi: 10.1108/14637151011093035. Berthod, O., Grothe-Hammer, M., M€ uller-Seitz, G., Raab, J. and Sydow, J. (2016), “From high-reliability organizations to high- reliability networks: the dynamics of network governance in the face of emergency”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 352-371, doi: 10.1093/jopart/muw050. Bevilacqua, M., Mazzuto, G. and Paciarotti, C. (2015), “A combined IDEF0 and FMEA approach to healthcare management reengineering”, International Journal of Procurement Management, Vol. 8, pp. 1-2. Bhakoo, V. and Choi, T. (2013), “The iron cage exposed: institutional pressures and heterogeneity across the healthcare supply chain”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 31, pp. 432-449. Bhamra, R., Dani, S. and Burnard, K. (2011), “Resilience: the concept, a literature review and future directions”, International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 49 No. 18, pp. 5375-5393. Borelli, G., Orr u, P.F. and Zedda, F. (2015), “Performance analysis of A healthcare supply chain for rfid-enabled process reengineering”, International Journal of Procurement Management, Vol. 8 Nos 1/2, pp. 169-181. Bowersox, D.J., Stank, T.P. and Daugherty, P. (1999), “Lean Launch: managing product introduction risk through response based logistics”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 16 No. 6, pp. 557-568. Breen, L. and Crawford, H. (2005), “Improving the pharmaceutical supply chain: assessing the reality of e-quality through e-commerce application in hospital pharmacy”, International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, Vol. 22 No. 6, pp. 572-590. Cai, J., Liu, X., Xiao, Z. and Liu, J. (2009), “Improving supply chain performance management: a systematic approach to analyzing iterative KPI accomplishment”, Decision Support Systems, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 512-521. Supply chain risk management in healthcare

- 24. Calil, S.J. and Ram ırez, E.F.F. (2000), “Engenharia clinica: parte I - origens (1942-1996)”, Semina: Ci^ encias Exatas e Tecnol ogicas, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 27-33. Campling, N.C., Pitts, D.G., Knight, P.V. and Aspinall, R. (2017), “A qualitative analysis of the effectiveness of telehealthcare devices (ii) barriers to uptake of telehealthcare devices”, Health Services Research, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 1-9. Carvalho, H. and Cruz Machado, V. (2007), “Designing principles to create resilient supply chains”, Proceedings of the 2007 Industrial Engineering Research Conference, Nashville. Carvalho, H., Cruz-Machado, V. and Tavares, J.G. (2012), “A mapping framework for assessing Supply Chain resilience”, International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 354-373. Cavalieri, M., Guccio, C. and Rizzo, I. (2017), “On the role of environmental corruption in healthcare infrastructures: an empirical assessment for Italy using DEA with truncated regression approach”, Health Policy, Vol. 121 No. 5, pp. 515-524. Chandra, C. (2008), “The case for healthcare supply chain management: insights from problem-solving approaches”, International Journal of Procurement Management, Vol. 1 No. 3. Chen, M.-F., Tsai, C.-L., Chen, Y.-H., Huang, Y.-W., Wu, C.-N., Chou, C., Chien, C.-H., Pei-Weng, T., Kao, T. and Lin, K.-P. (2018), “Web-based experience sharing platform on medical device incidents for clinical engineers in hospitals”, Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 835-844. Chiarini, A., Opoku, A. and Vagnoni, E. (2017), “Public healthcare practices and criteria for a sustainable procurement: a comparative study between UK and Italy”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 162, pp. 391-399. Coelho, L.C., Follman, N. and Taboada, M.C.R. (2009), “O impacto do compartilhamento de informaç~ oes na reduç~ ao do efeito chicote na cadeia de abastecimento”, Revista Gest~ ao and Produç~ ao, Vol. 16 No. 4, pp. 571-583. Cooper, M.C., Ellram, L.M., Gardner, J.T. and Hanks, A.M. (1997), “Meshing multiple alliances”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 67-89. Croxton, K., Dastugue, S., Lambert, D. and Rogers, D. (2001), “The supply chain management processes”, International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 12 No. 2, pp. 13-16. Cruz, A.M. and Guar ın, M.R. (2017), “Determinants in the number of staff in hospitals’ maintenance departments: a multivariate regression analysis approach”, Journal of Medical Engineering and Technology, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 151-164. Cruz, A.M. and Haugan, G.L. (2019), “Determinants of maintenance performance: a resource-based view and agency theory approach”, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, Vol. 51, pp. 33-47. Del Solar, J.S.F.A. and Mendes, C.J.M.R.(2017), “Brazilian clinical engineering regulations: health equipment management and conditions for professional exercise”, Research on Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 301-312. Dhillon, B.S. (2000), Medical Device Reliability and Associated Areas, 1st ed., CRC Press, Cleveland, Ohio, p. 264, ISBN: 10: 1420042238. Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Childe, S.J., Papadopoulos, T., Blome, C. and Luo, Z. (2019), “Antecedents of resilient supply chains: AnEmpirical study”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 66 No. 1, pp. 8-18. Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Bryde, D.J., Dwivedi, Y.K. and Papadopoulos, T. (2020), “Blockchain technology for enhancing swift-trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting”, International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 58 No. 11, pp. 3381-3398, doi: 10.1080/00207543.2020.1722860. Eiro, N.Y. and Torres Junior, A.S. (2015), “Comparative study: TQ and Lean Production ownership models in health services”, Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 846-854. BIJ

- 25. Elleuch, H., Hachicha, W. and Chabchoub, H. (2013), “A combined approach for supply chain risk management: description and application to a real hospital pharmaceutical case study”, Journal of Risk Research, Vol. 17 No. 5, pp. 641-663, doi: 10.1080/13669877.2013.815653. Fan, Y. and Stevenson, M. (2018), “A review of supply chain risk management: definition, theory, and research agenda”, International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, Vol. 48 No. 3, doi: 10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2017-0043. Fan, W., Gu, J., Tang, H. and Gao, X. (2011), “Risk management in end-to-end global supply chain”, Proceedings of 11th International Conference of Chinese Transportation Professionals (ICCTP), Nanjing. Fang, D. and Weng, W. (2010), “KPI evaluation system of location decision for plant relocation from the view of the entire supply chain optimization”, Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Automation and Logistics, Macau, Hong Kong. Farley, J.M., Suraweera, I., Perera, W.L.S.P., Hess, J. and Ebi, K.L. (2017), “Evaluation of flood preparedness in government healthcare facilities in Eastern Province, Sri Lanka”, Global Health Action, Vol. 10 No. 1, doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1331539. Gelderman, C.J., Semeijn, J. and Vluggen, R. (2017), “Development of sustainability in public sector procurement”, Public Money and Management, Vol. 37 No. 6, pp. 435-442, doi: 10.1080/09540962. 2017.1344027. Gligor, D., Bozkurt, S., Russo, I. and Omar, A. (2019), “A look into the past and future: theories within supply chain management, marketing and management”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 170-186. Gonçalves, L., Navarro, J.B. and Sala, R. (2019), “Spanish validation of the Benchmark Resilience Tool (short-form version) to evaluate organisational resilience”, Safety Science, Vol. 111, pp. 94-101. Grudinschi, D., Sintonen, S. and Hallikas, J. (2014), “Relationship risk perception and de terminants of the collaboration fluency of buyer–supplier relationships in public service procurement”, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 20, pp. 82-91. Hablia, I., Whiteb, S., Sujanc, M., Harrisond, S. and Ugartee, M. (2018), “What is the safety case for health IT? A study of assurance practices in England”, Safety Science, Vol. 110, pp. 324-335. Haeri, A., Hosseini-Motlagh, S.-M., Samani, M.R.G. and Rezaei, M. (2020), “A mixed resilient-efficient approach toward blood supply chain network design”, International Transactions in Operations Research, Vol. 27, pp. 1962-2001. Haimes, Y.Y. (2006), “On the definition of vulnerabilities in measuring risks to infrastructures”, Risk Analysis, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 293-296. Hall, N. (2016), “The rise of inventory management in operating theatre departments”, Journal of Perioperative Practice, Vol. 26 No. 10, pp. 221-224. Hallikas, J., Virolainen, V.M. and Tuominen, M. (2002), “Risk analysis and assessment in network environments: a dyadic case study”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 78 No. 1, pp. 45-55. Hallikas, J., Karvonen, I., Pulkkinen, U., Virolainen, V.-M. and Tuominen, M. (2004), “Risk management processes in supplier networks”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 90 No. 1, pp. 47-58. Hamdi, F., Ghorbel, A., Masmoudi, F. and Dupont, L. (2015), “Optimization of a supply portfolio in the context of supply chain risk management: literature review”, Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 763-788. Heidari, S.S., Khanbabaei, M. and Sabzehparvar, M. (2018), “A model for supply chain risk management in the automotive industry using fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy TOPSIS”, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 25 No. 9, pp. 3831-3857. Helo, J.R.P. (2016), “Developing service supply chains by using agent based simulation”, Industrial Management and Data Systems, Vol. 116 No. 2, pp. 255-270. Supply chain risk management in healthcare