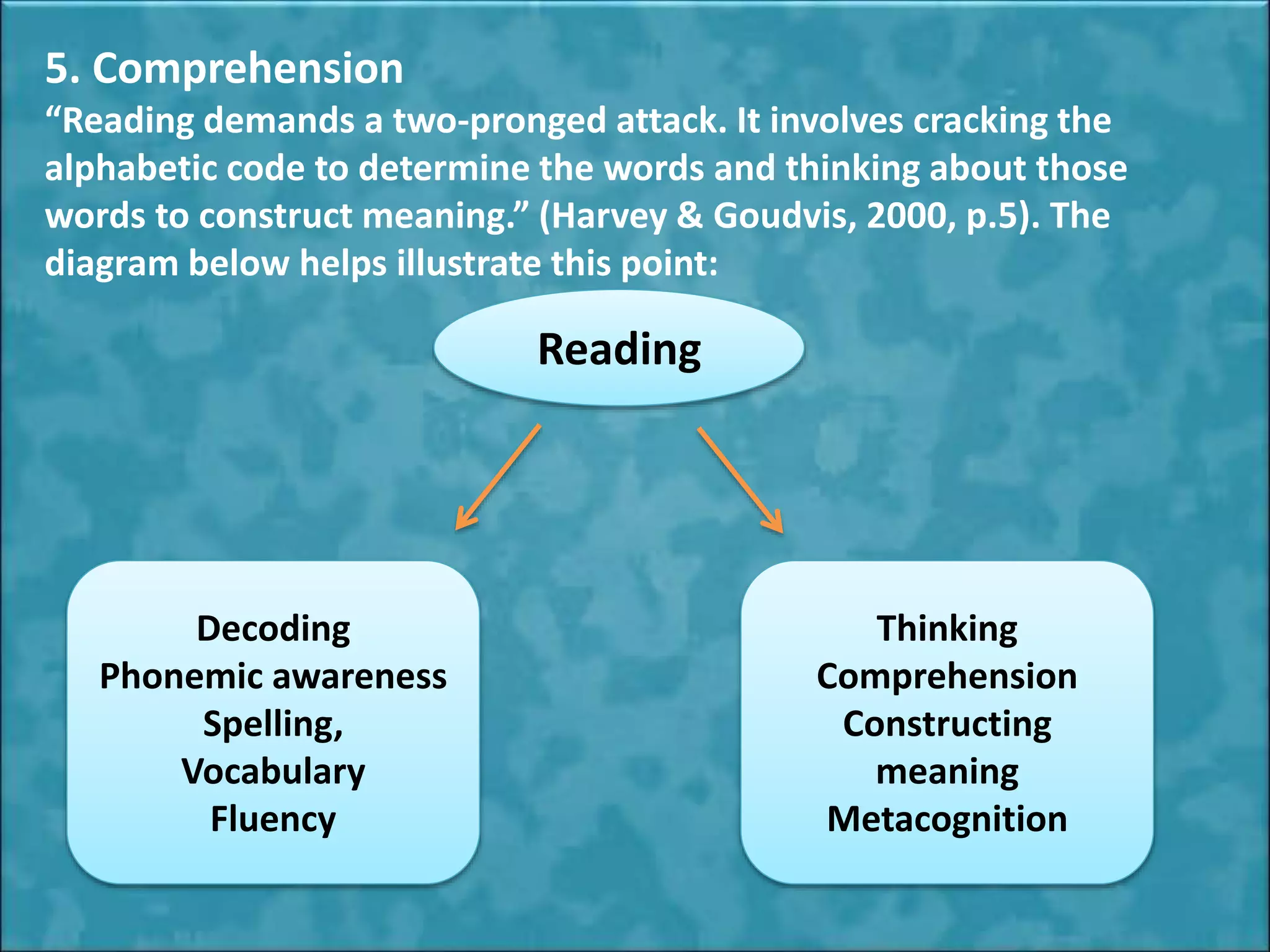

The document discusses teaching reading and provides information on several key areas of reading instruction including phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. It describes 5 levels of phonemic awareness instruction from rhyming and alliteration to phoneme segmentation. It also outlines objectives of reading instruction, defines what reading is, and describes the 5 areas of the National Reading Panel's framework for reading instruction. Additionally, it discusses strategies that can be used during the three stages of teaching reading: pre-reading, reading, and post-reading. The goal is to help students understand and construct meaning from texts.