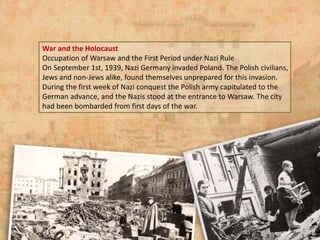

Warsaw, the capital of Poland, became a significant center for the Jewish community in Europe by the early 20th century, with a vibrant cultural and political life despite facing economic hardships. The establishment of the ghetto in 1940 marked the beginning of severe persecution, culminating in mass deportations and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, which was a significant act of resistance. The ghetto's destruction and the subsequent survival of a small number of Jews in bunkers highlighted the immense struggle against Nazi oppression during the Holocaust.

![Establishment of the Ghetto

In mid-November 1940, an area in the middle of the northern Jewish neighborhood was

sealed off, including inside it the predominantly Jewish streets.

"[T]he ghetto was sealed off. They concentrated all in the people in a few streets, in one

particular quarter. Those who lived in the streets that weren't to be part of this ghetto,

had to move to the streets that the Germans had designated for the Jews. Our street was

divided in the middle by the wall, with the non-even side for the Christians. We lived in

Number 30, and stayed. It was forbidden to leave through this street. They made an

entrance in the parallel street, and that's where we would leave."

Testimony of Rachel Rubin, Yad Vashem Archives, O.3/10316](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/warsawgood-150330030326-conversion-gate01/85/Warsaw-Ghetto-10-320.jpg)

![Sources:

Havi Ben Sasson and Hava Baruch (ed.), Warsaw: Polish Jewry Between the Two

World Wars (Student's Booklet) [heb.], Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

Israel Gutman, Warsaw entry, The Encyclopedia of the Holocaust [Heb.], Yad

Vashem and Sifriyat Hapoalim, 1990.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/warsawgood-150330030326-conversion-gate01/85/Warsaw-Ghetto-19-320.jpg)