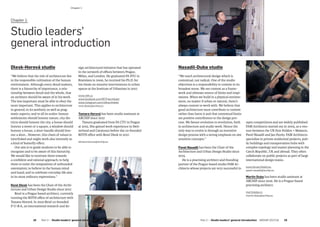

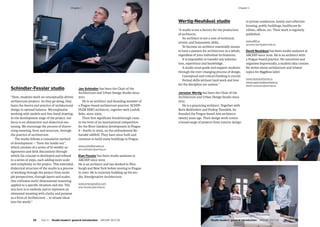

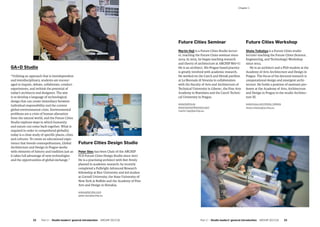

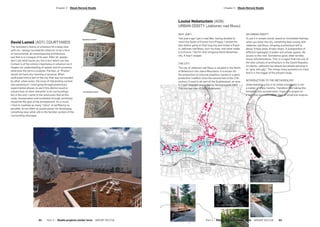

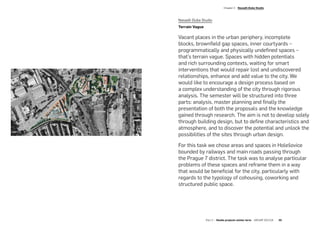

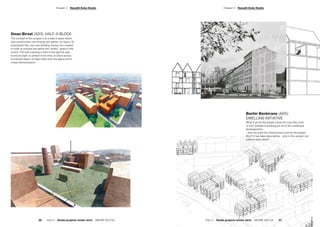

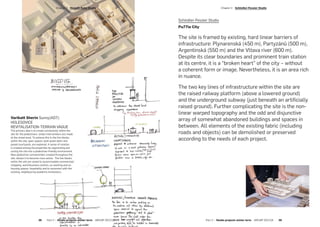

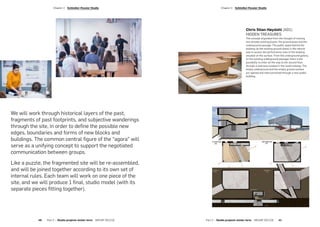

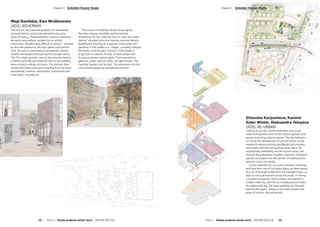

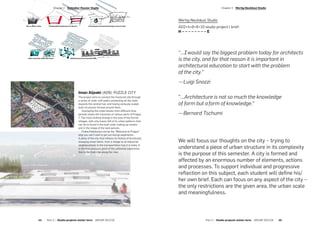

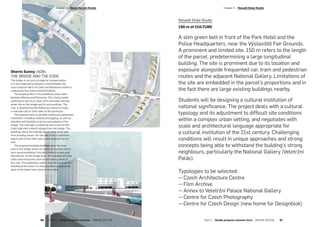

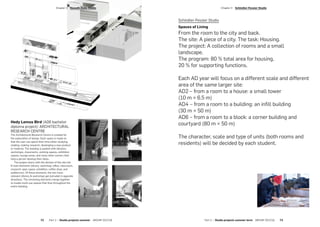

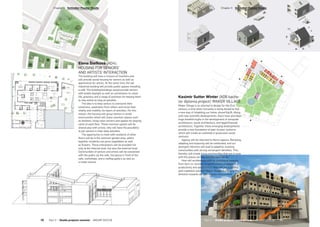

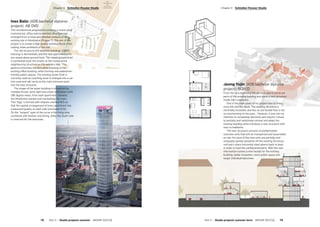

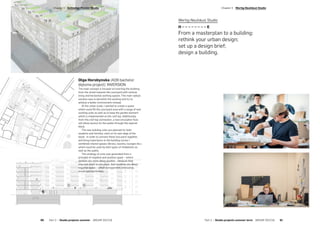

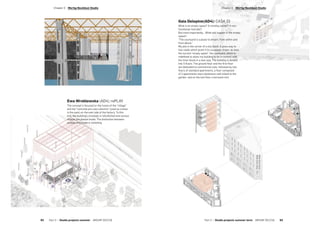

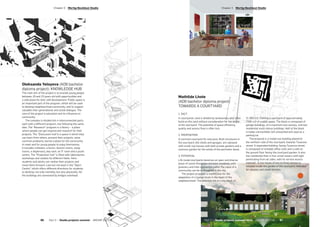

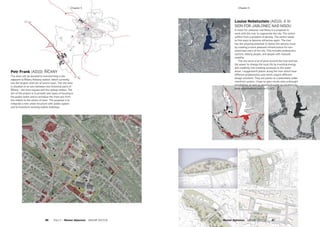

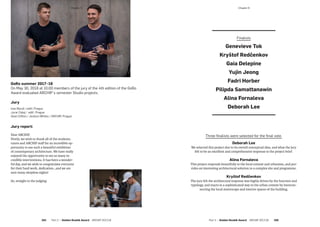

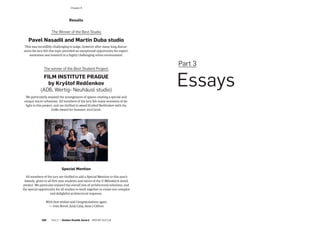

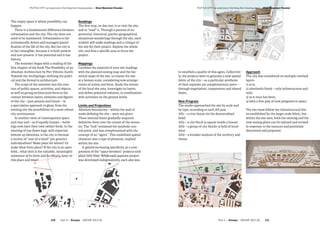

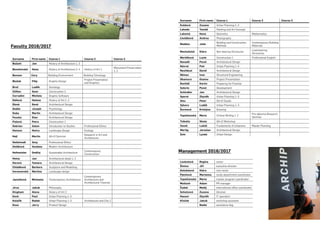

The 2017/2018 yearbook for ARCHIP provides an overview of the academic year, highlighting architectural design studio projects, essays, and significant events in architectural education. It emphasizes the vertical studio model that encourages collaboration among students of different years and outlines various workshops and awards that took place throughout the year. The yearbook also showcases the innovative and international nature of the school, including a diverse graduating class and participation in community and academic events.