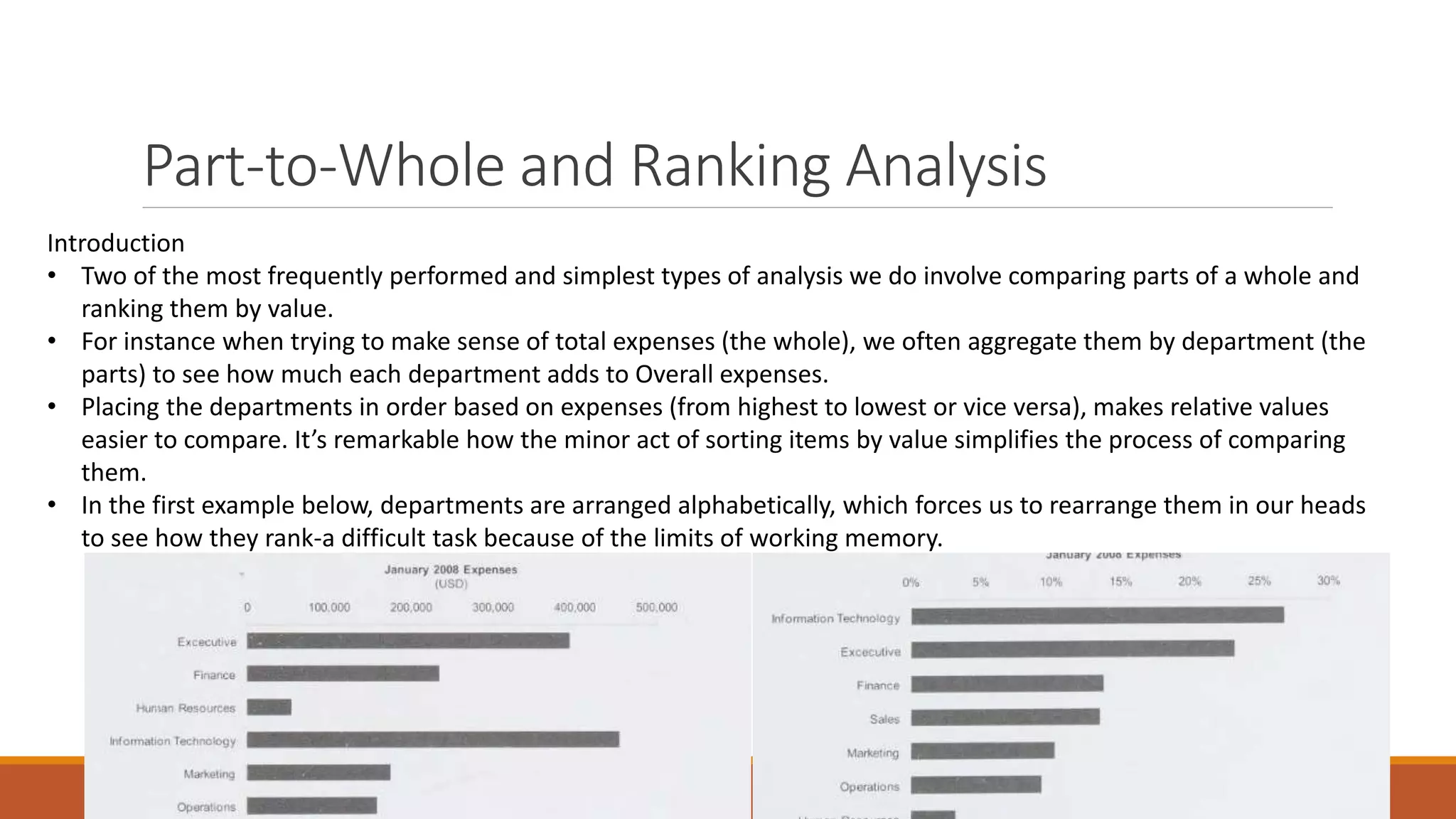

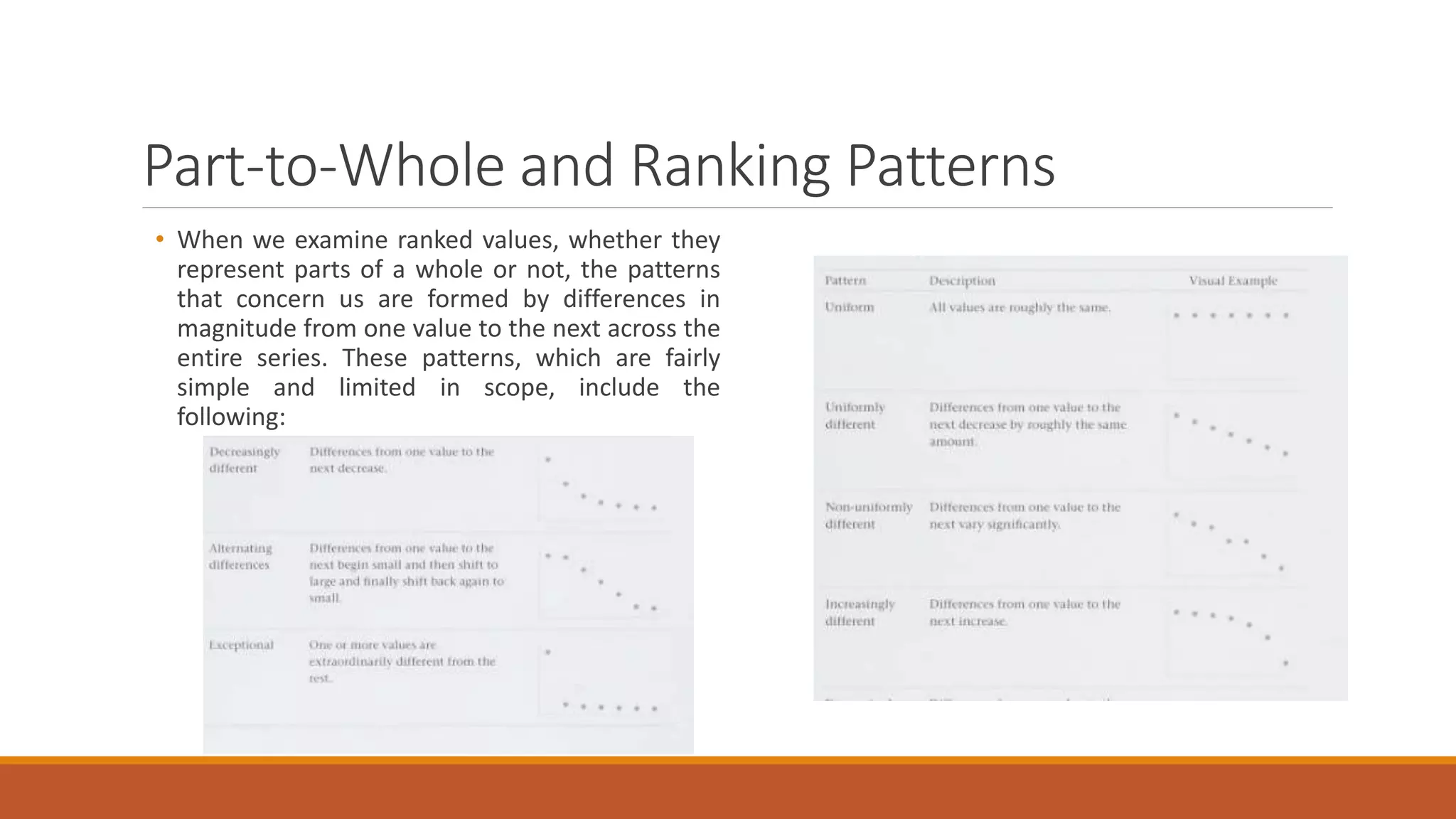

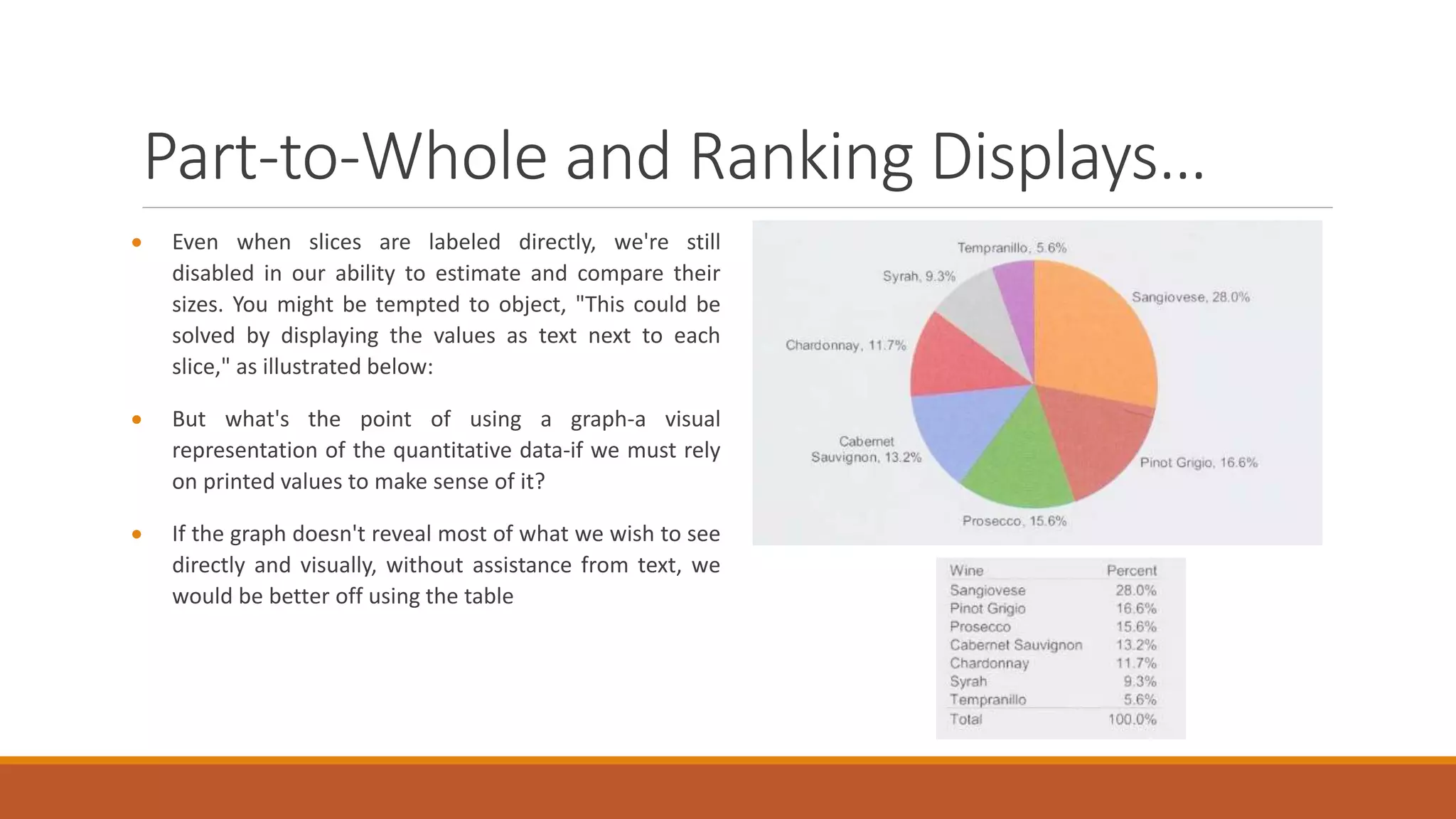

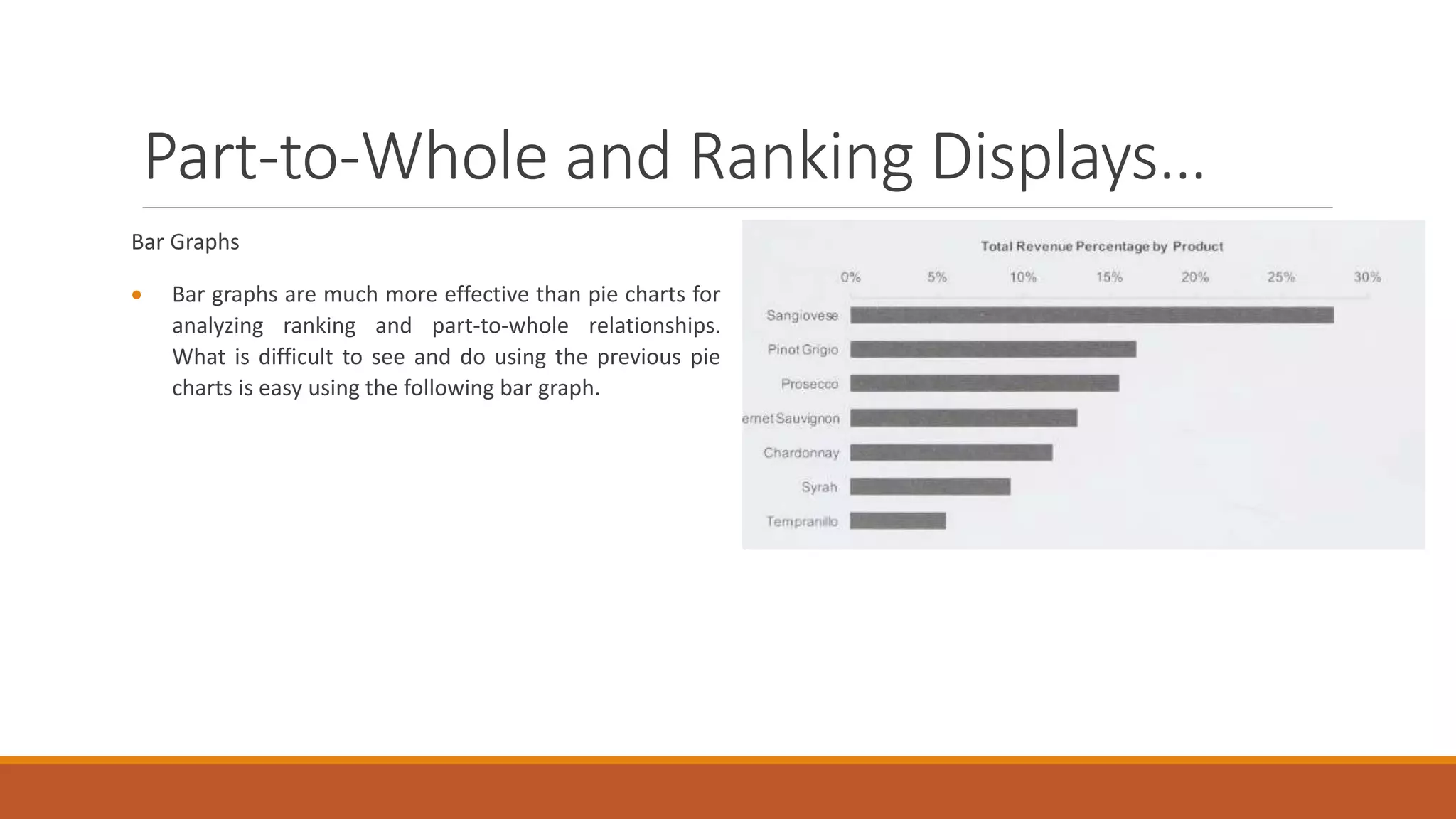

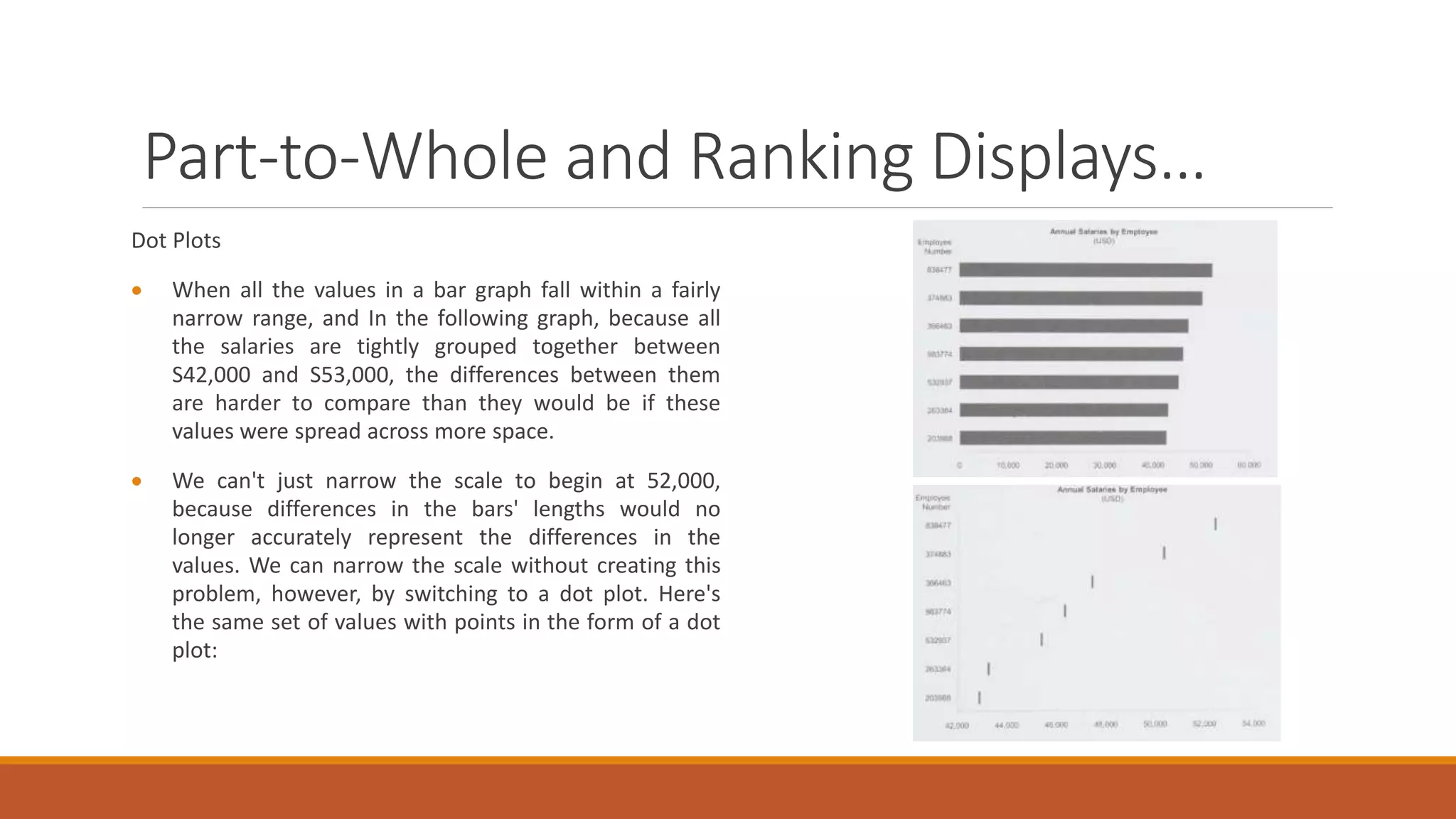

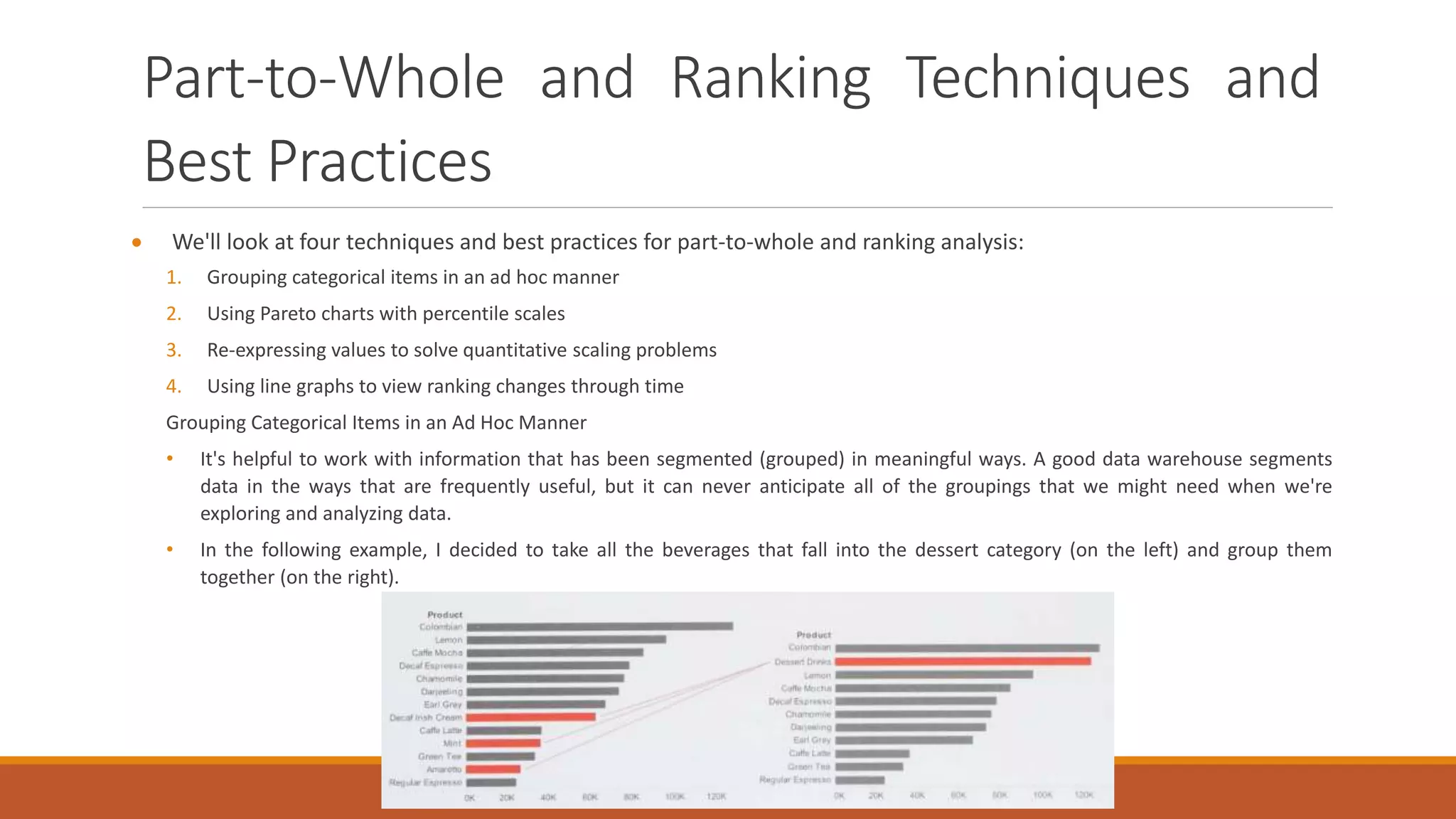

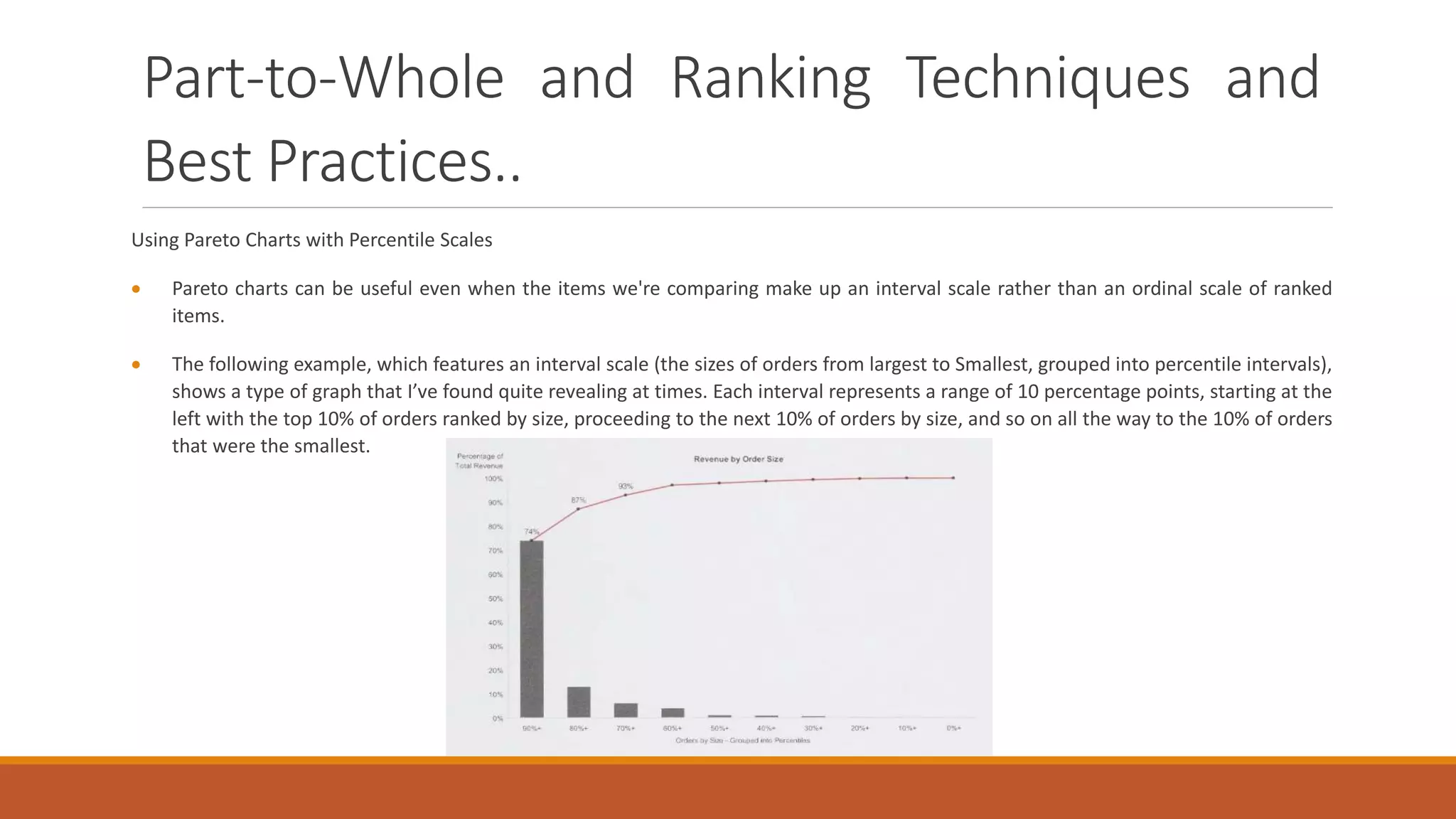

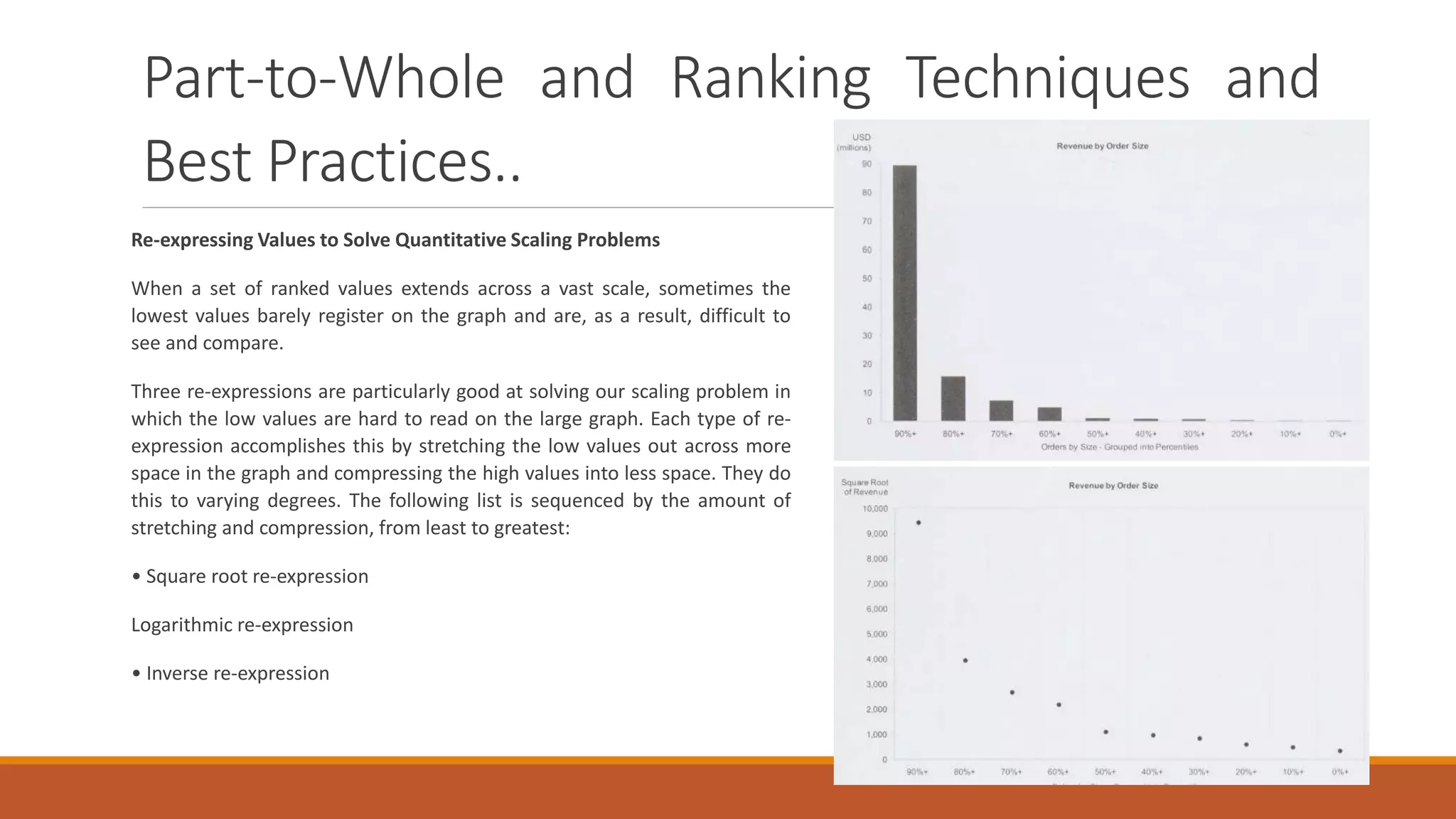

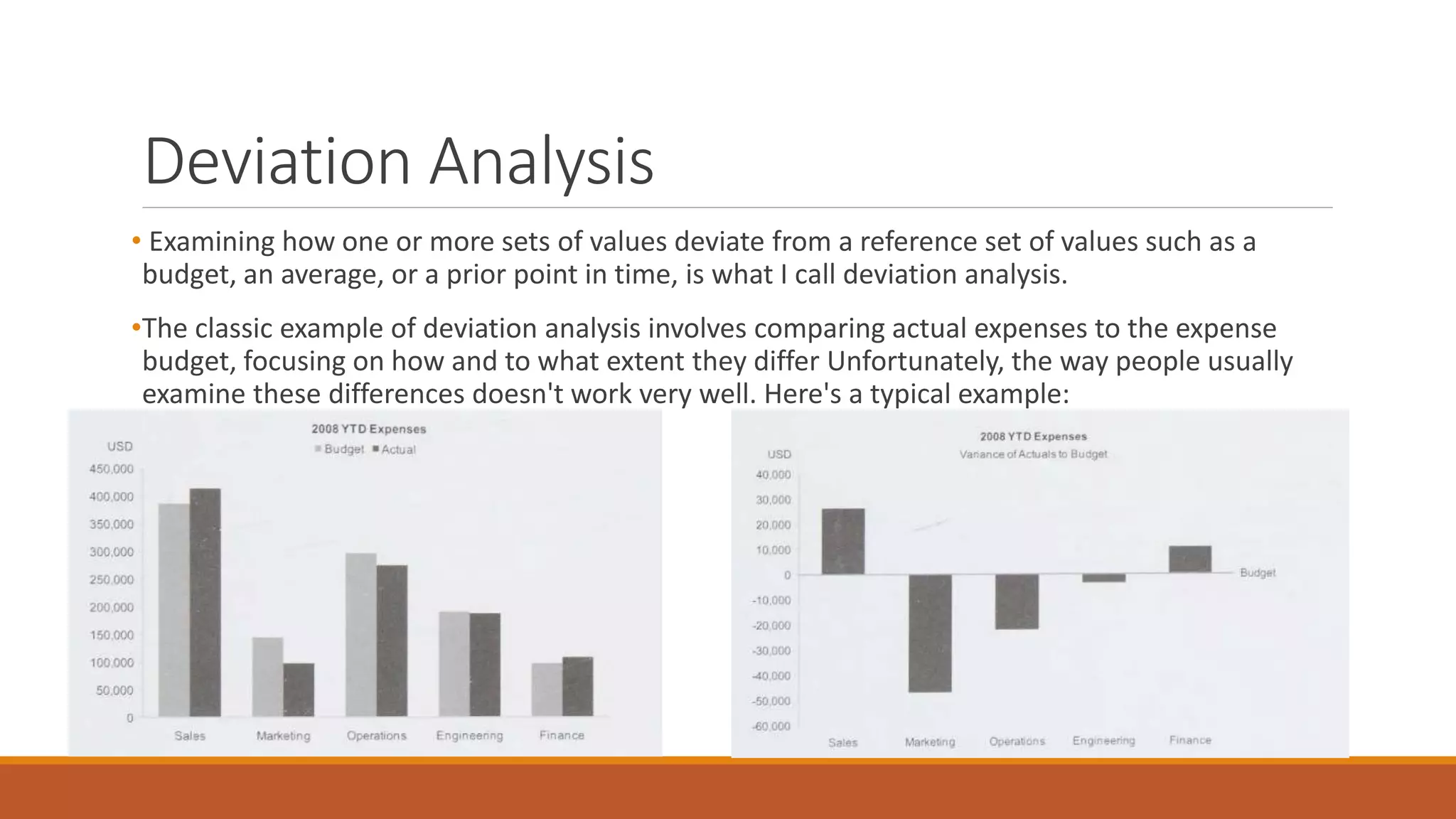

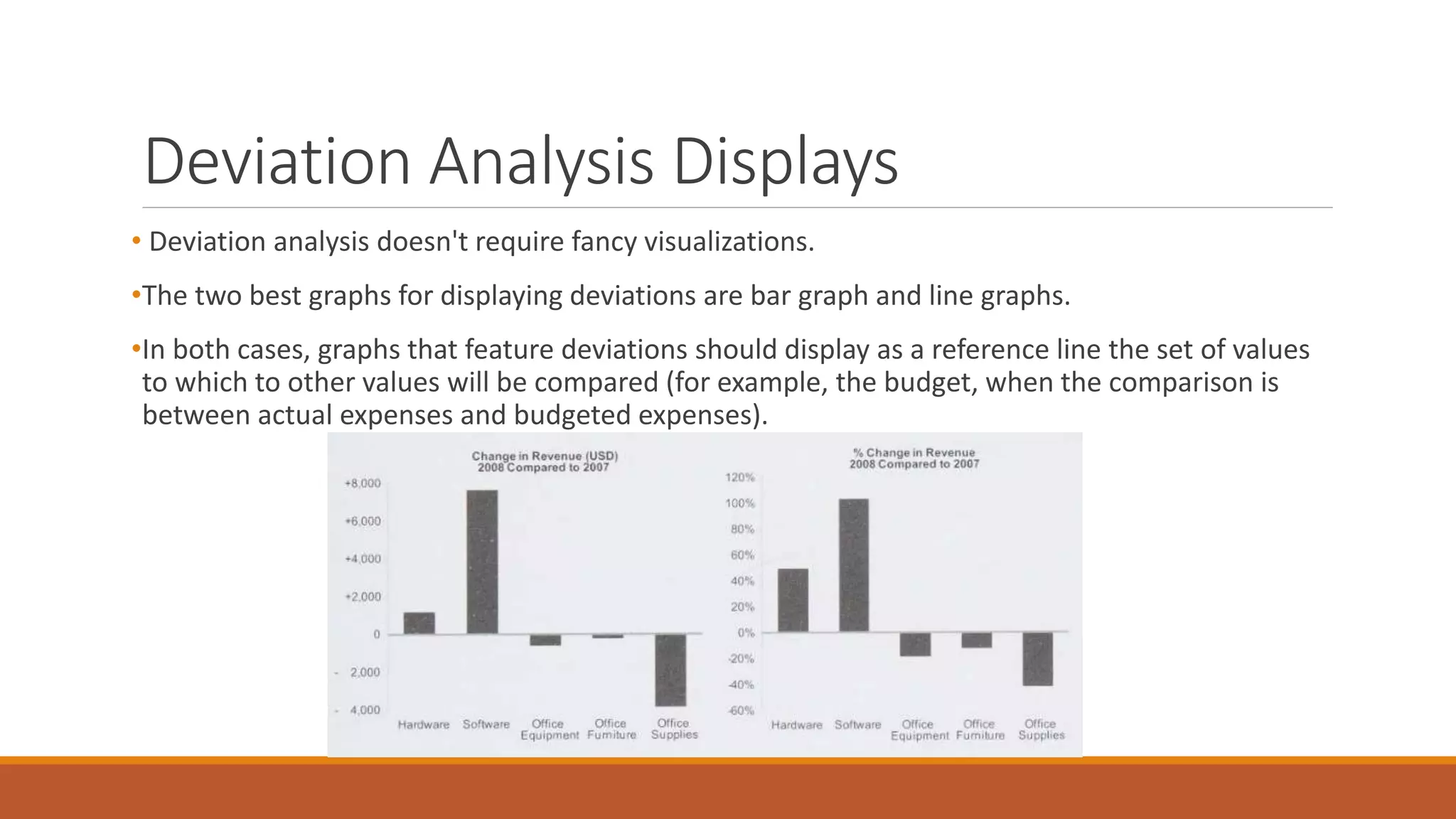

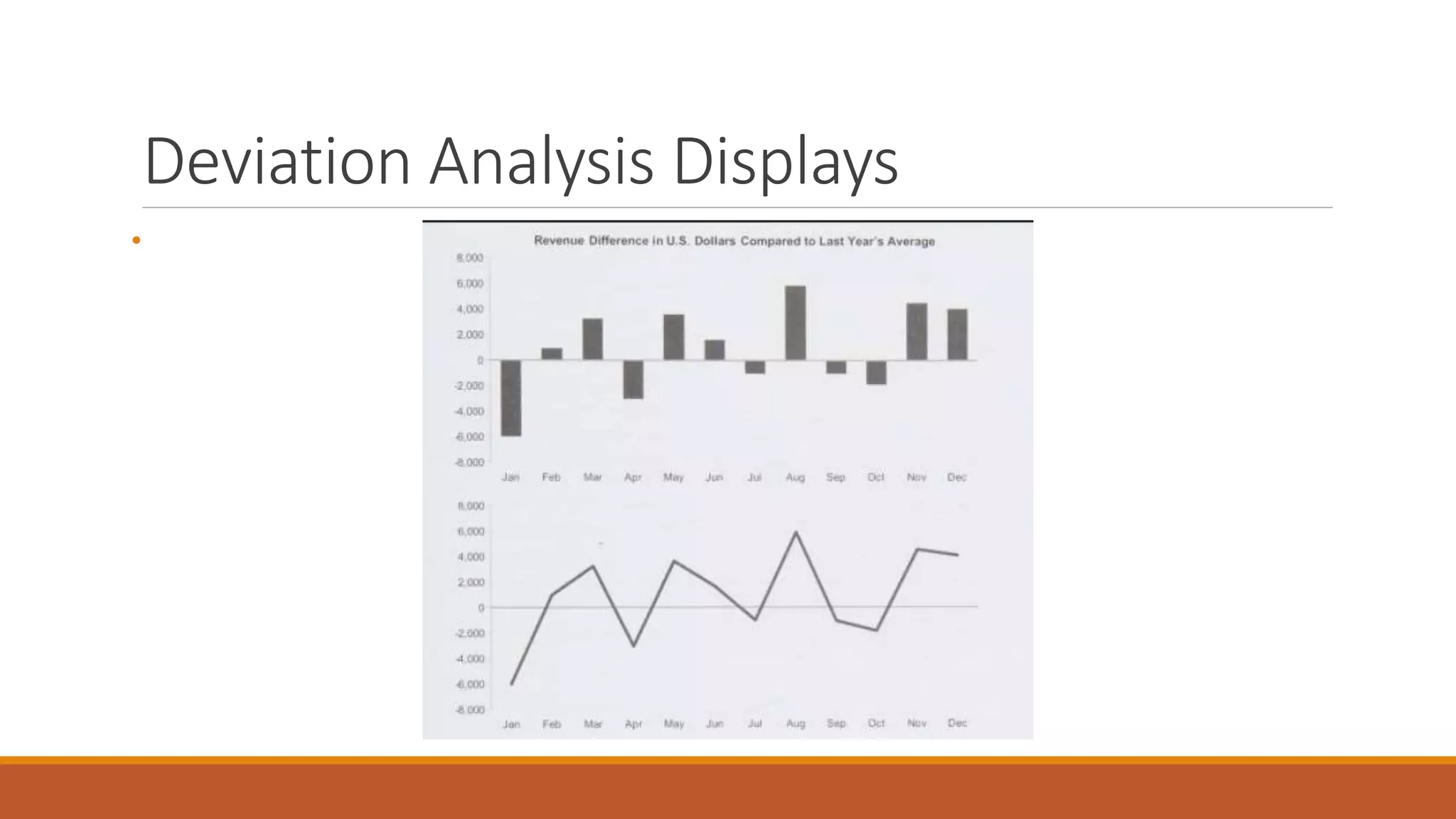

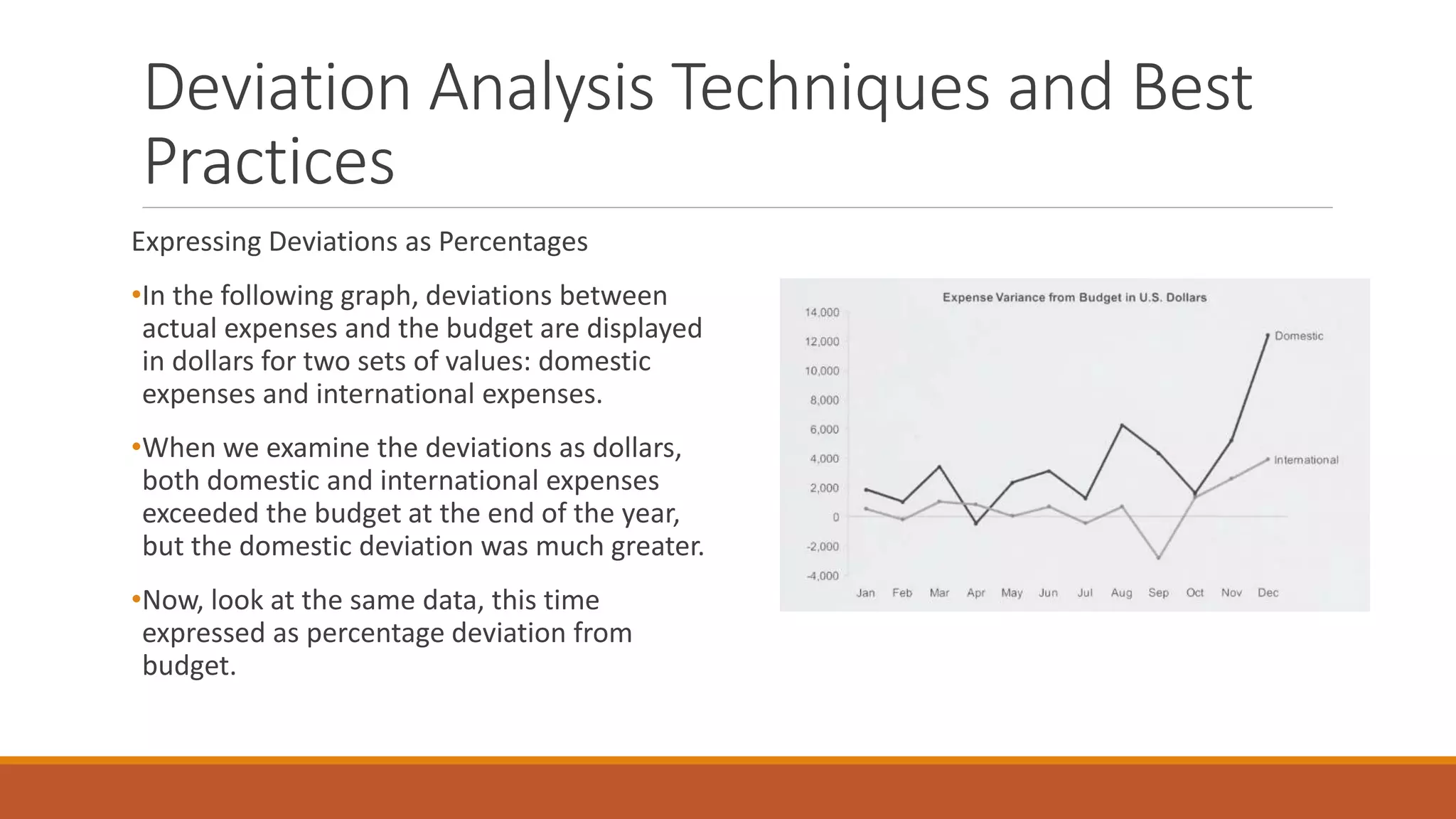

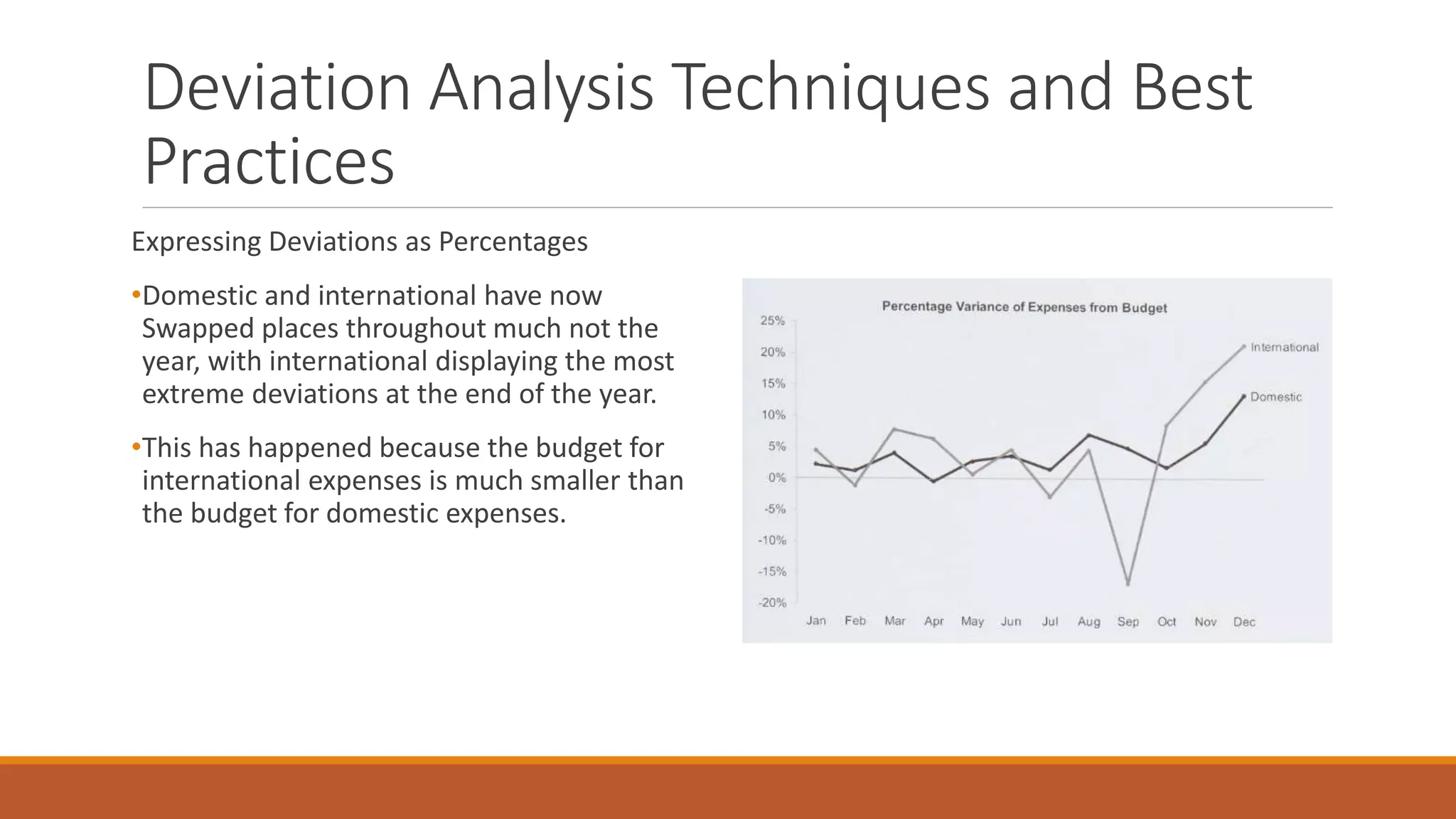

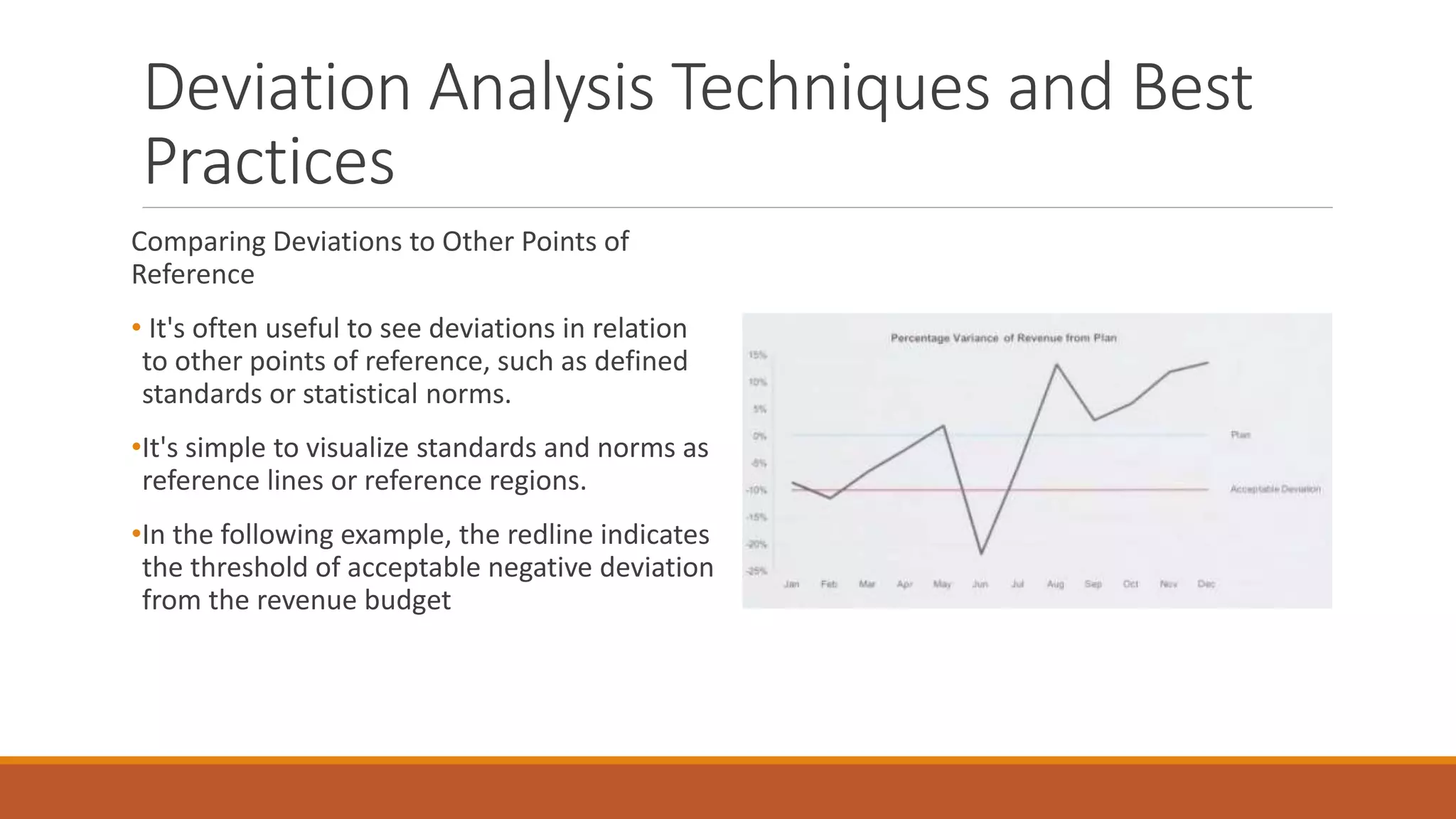

This document discusses techniques for analyzing time-series data, rankings, and deviations from reference values or averages. It covers part-to-whole analysis using pie charts and bar graphs to compare proportions or rank categories by value. Ranking displays like dot plots are recommended when values are tightly grouped. The document also discusses expressing deviations as percentages, comparing to other references like budgets or standards, and using techniques like re-expressing values to solve scaling issues.