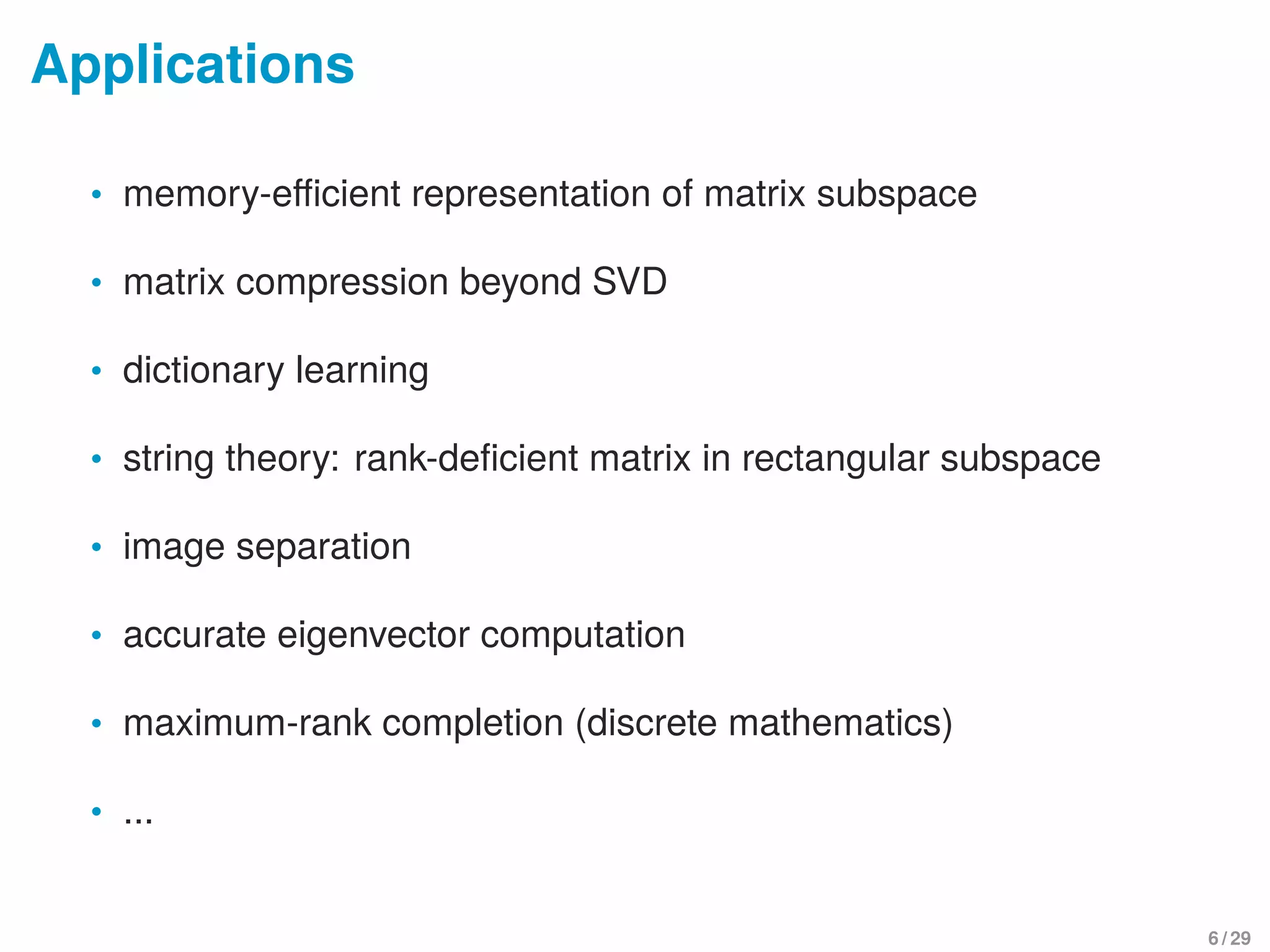

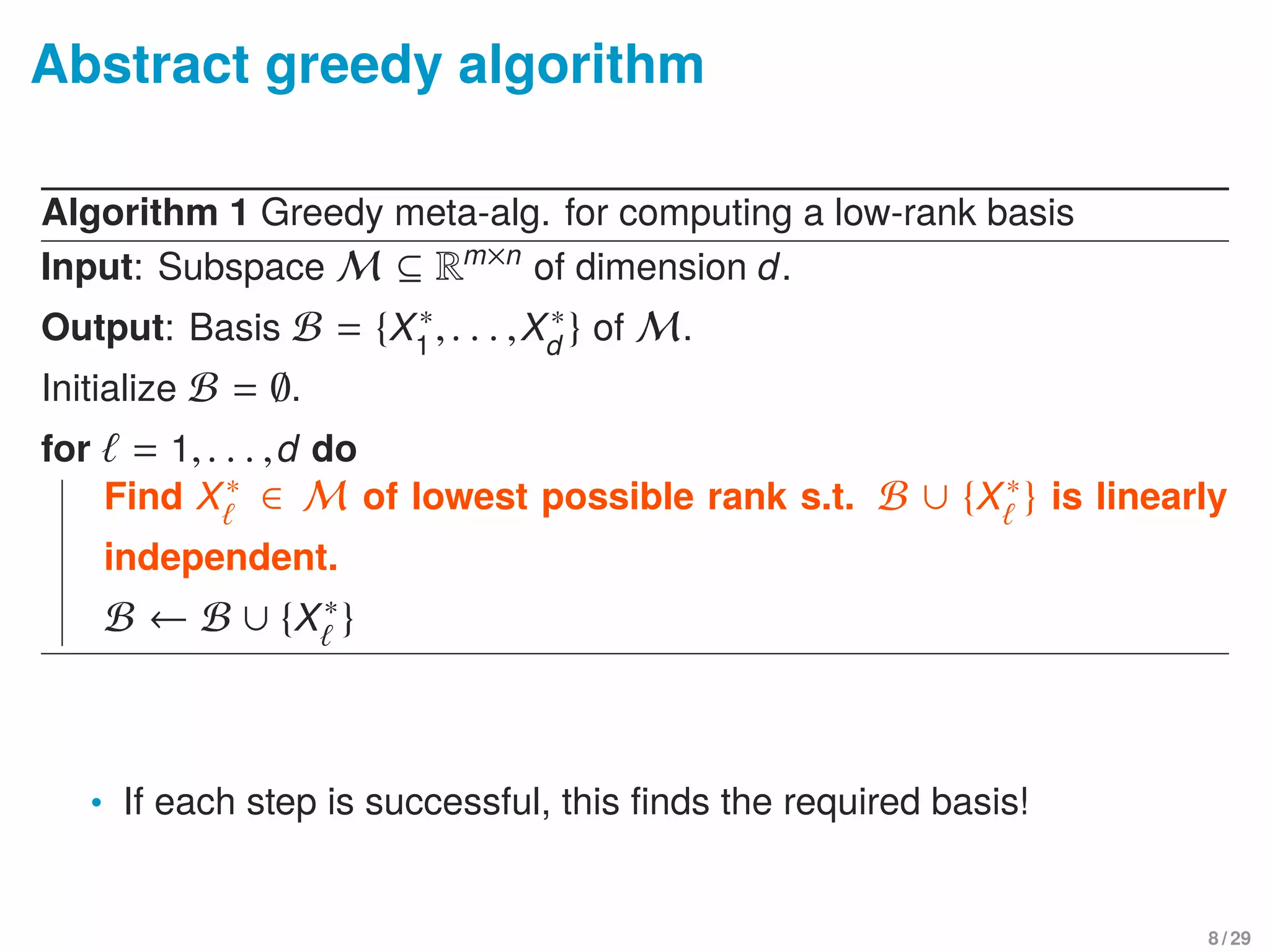

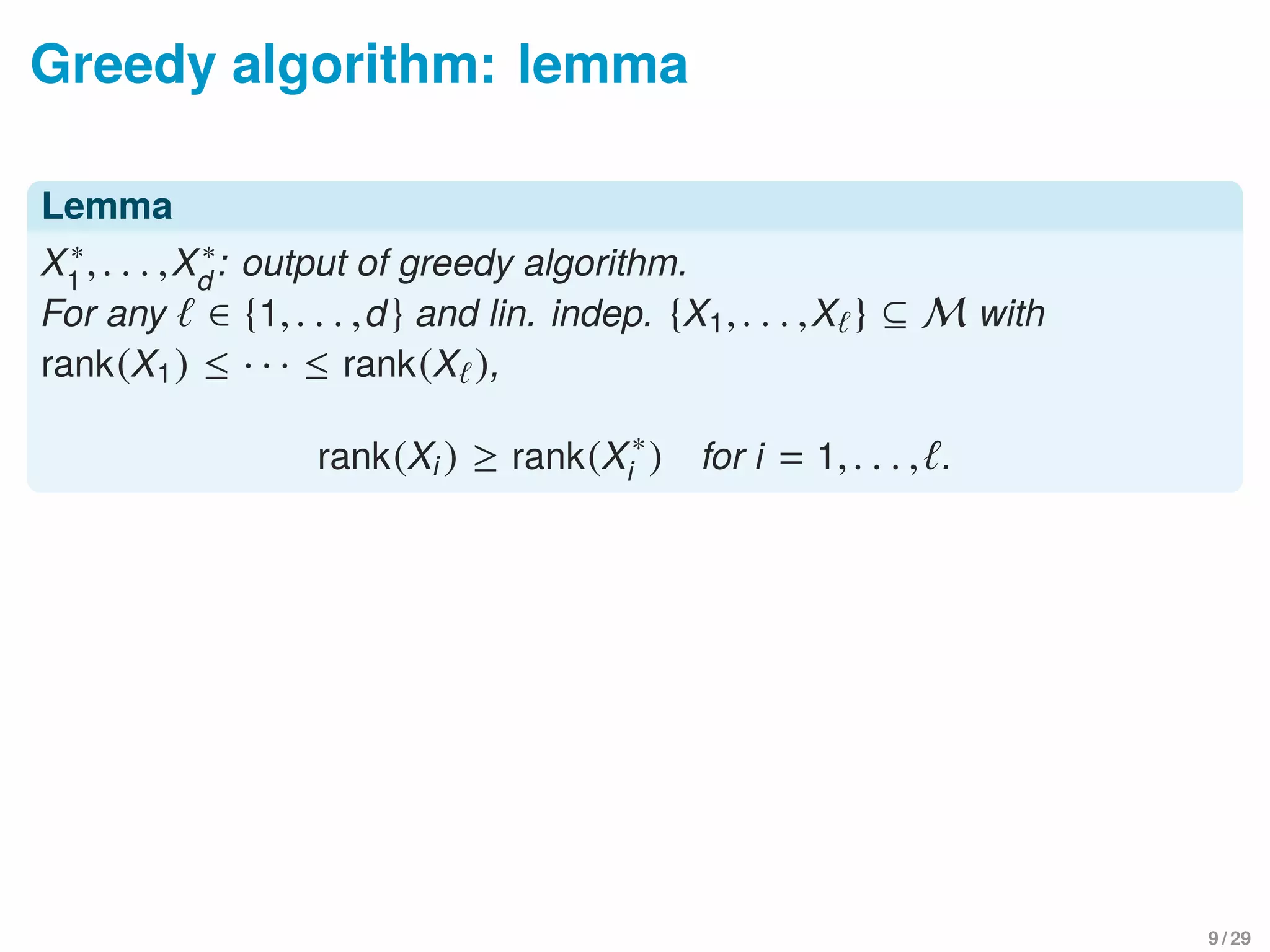

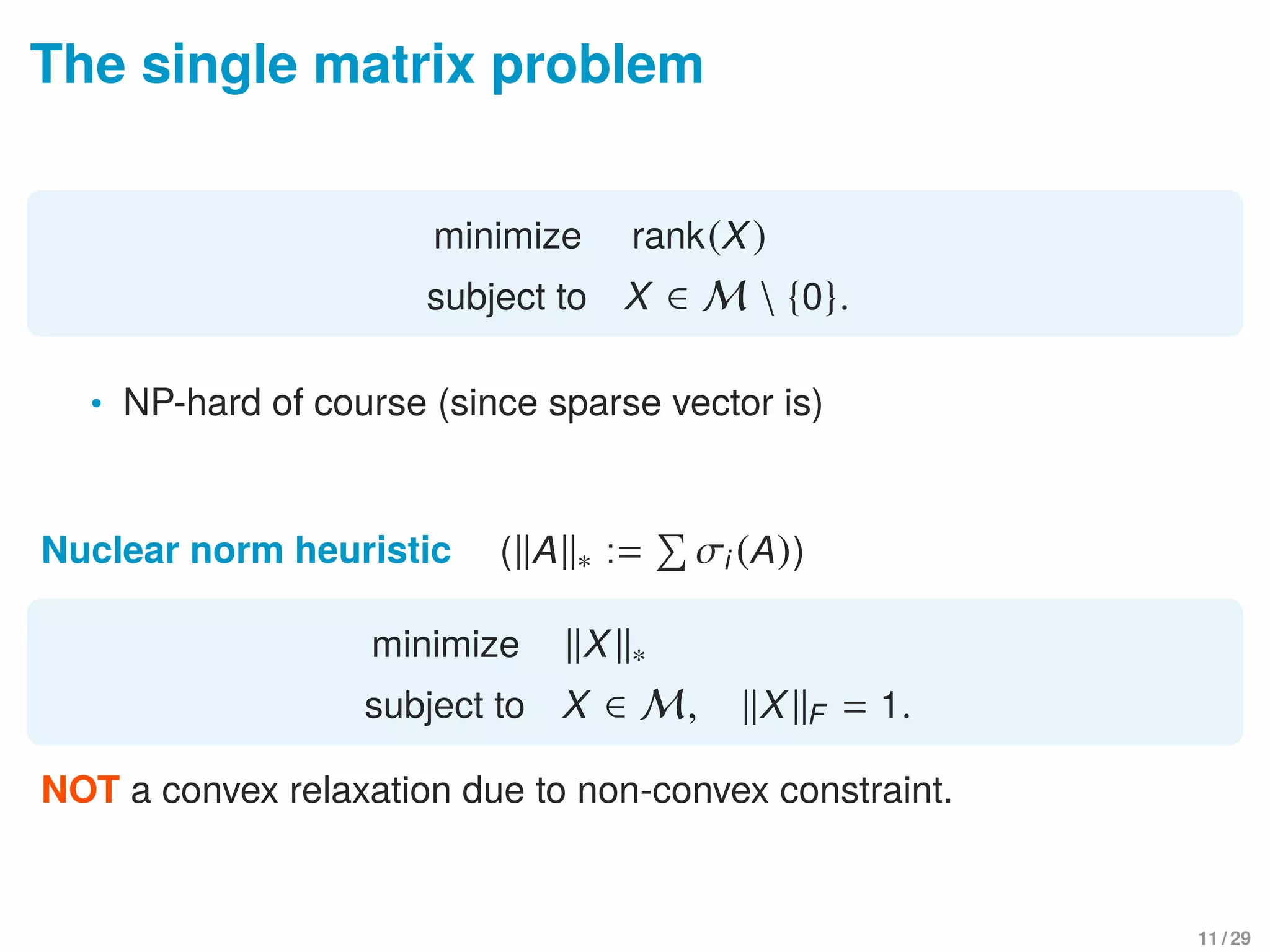

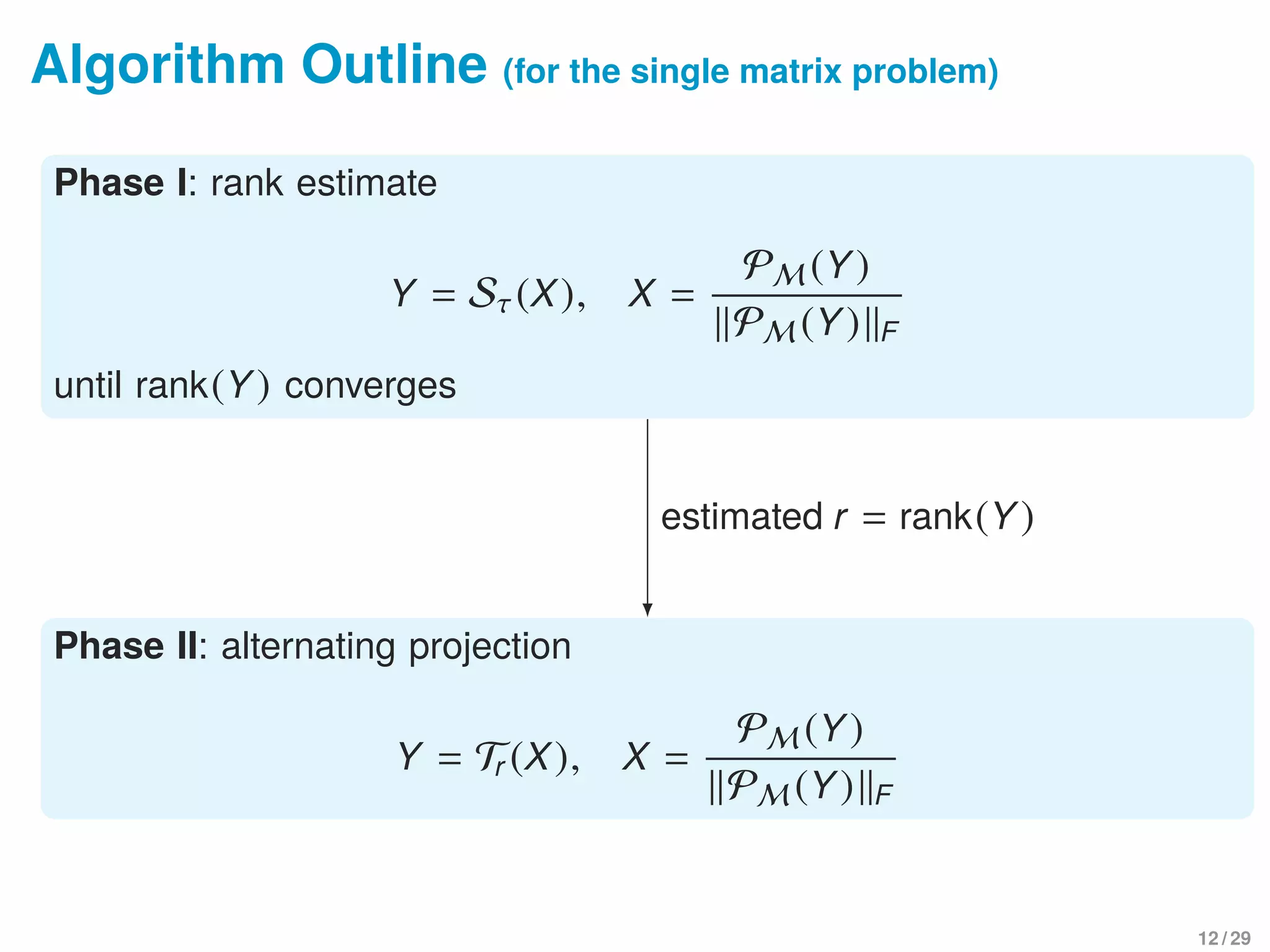

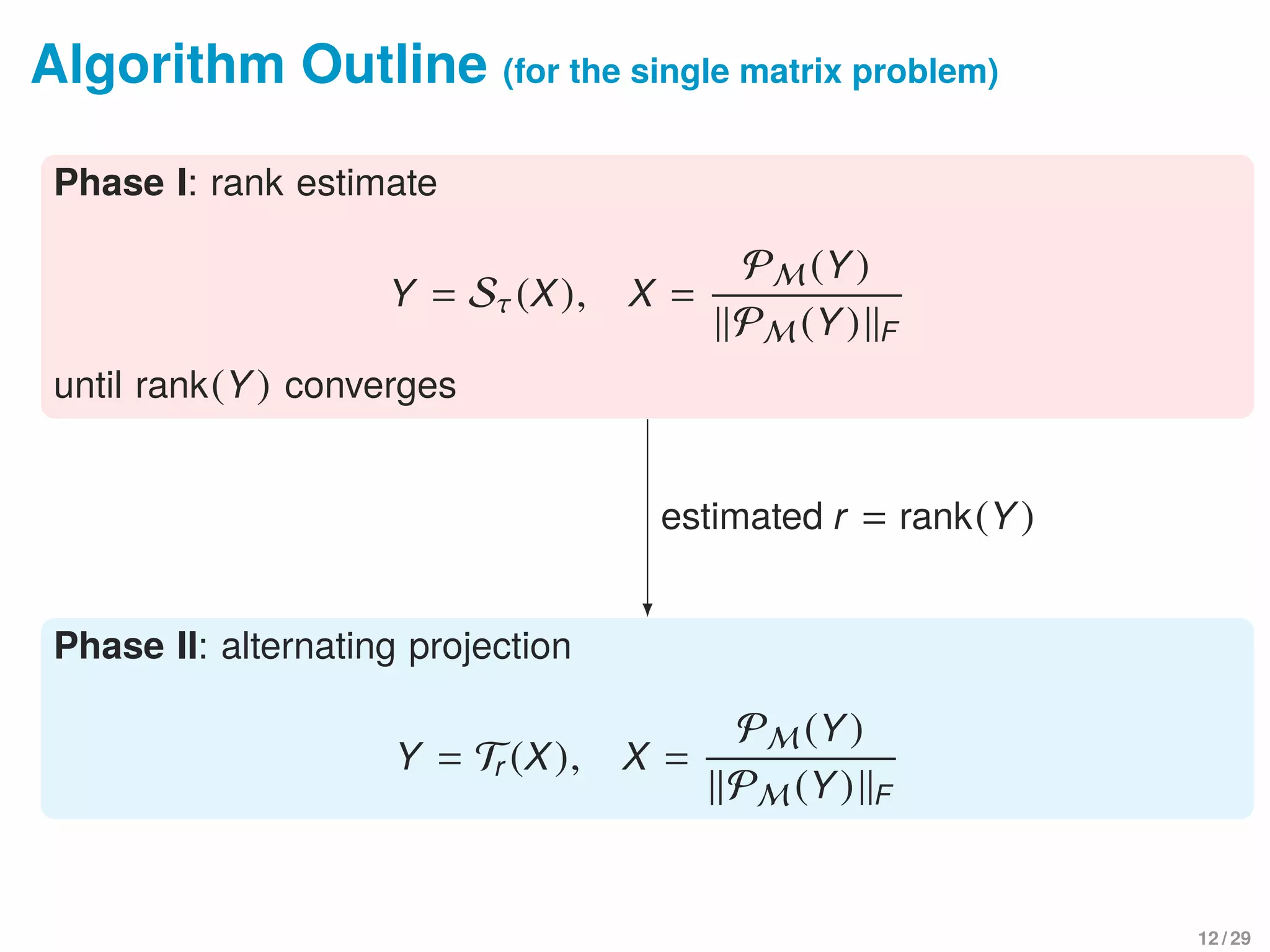

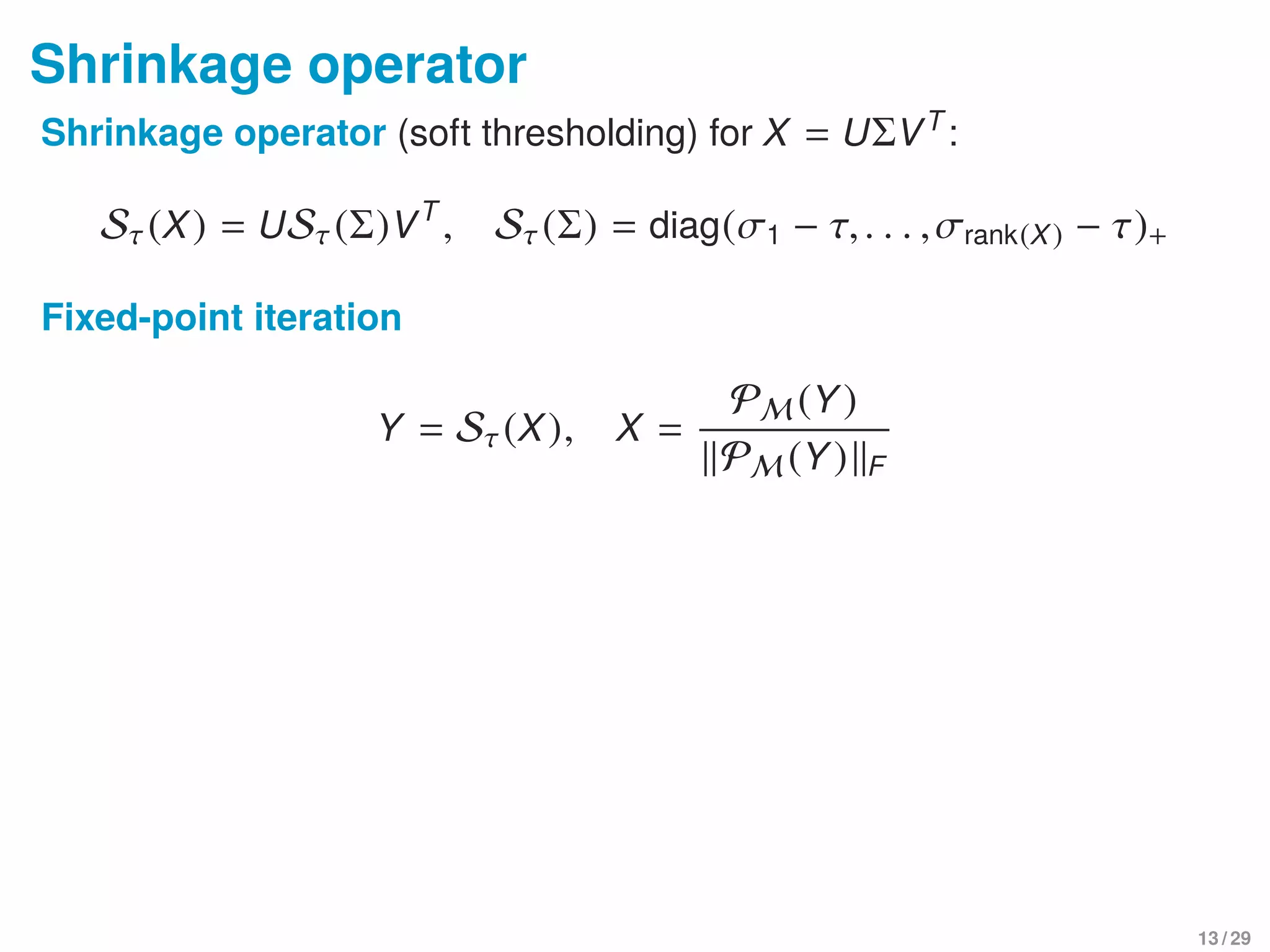

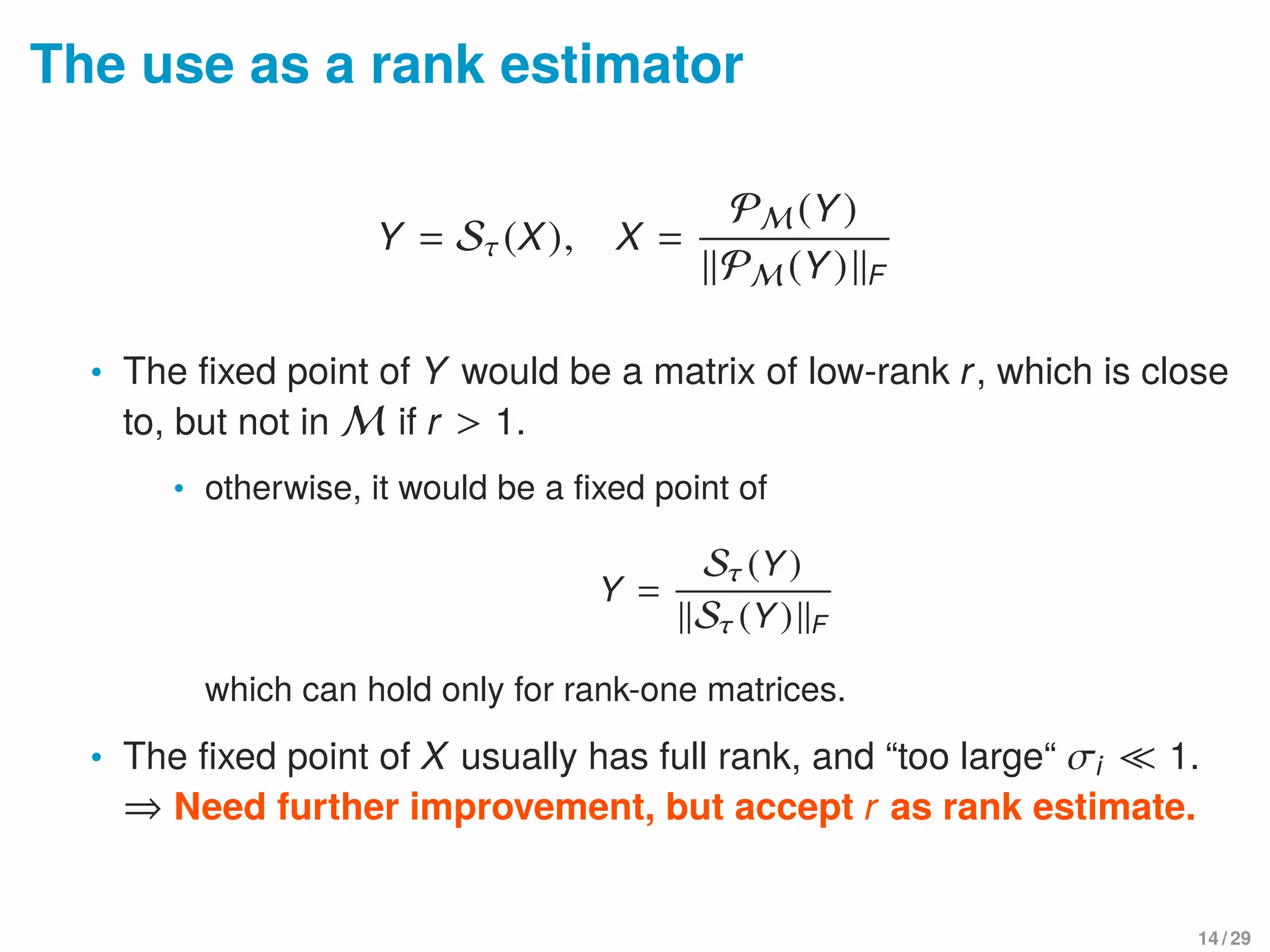

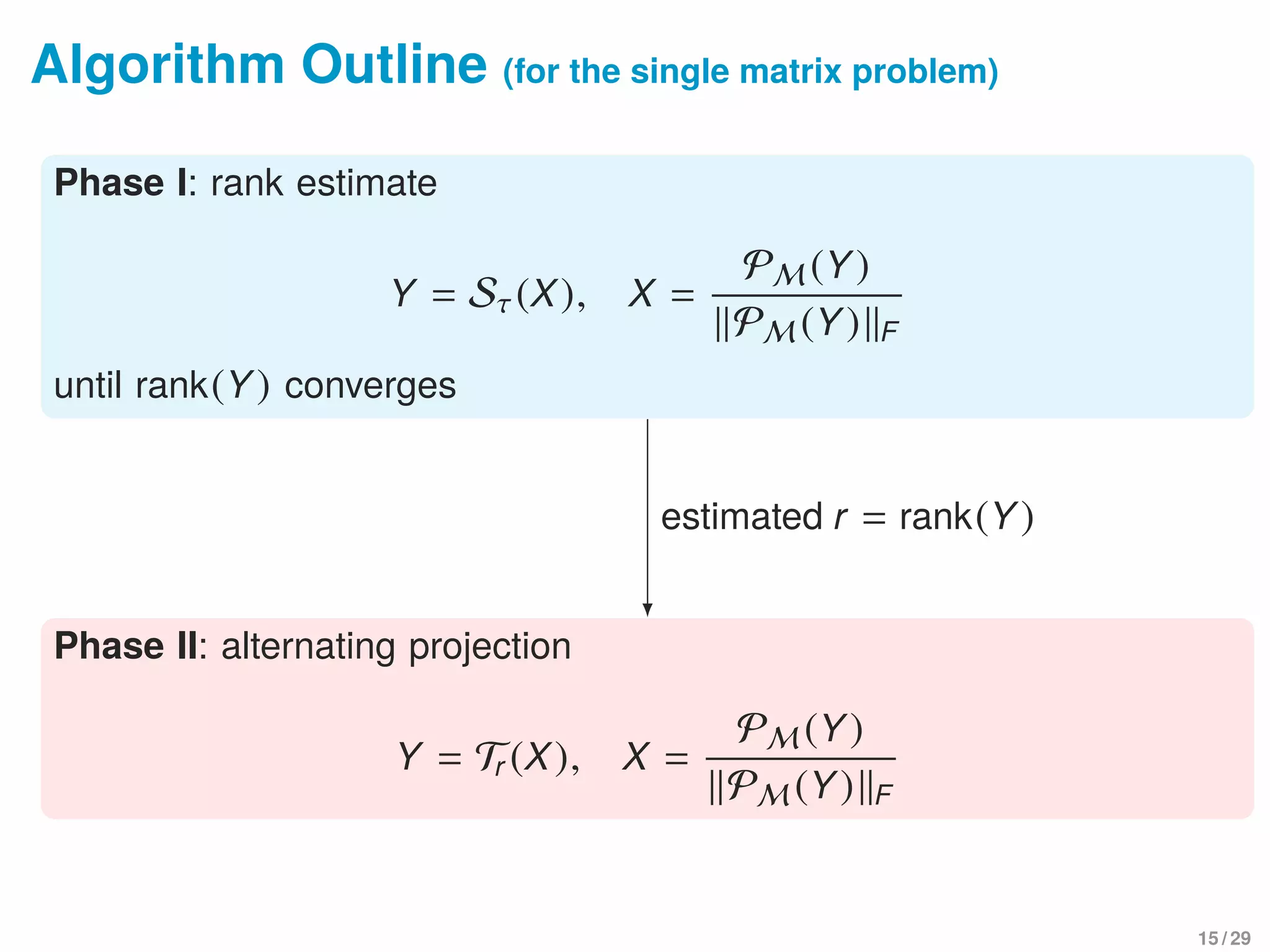

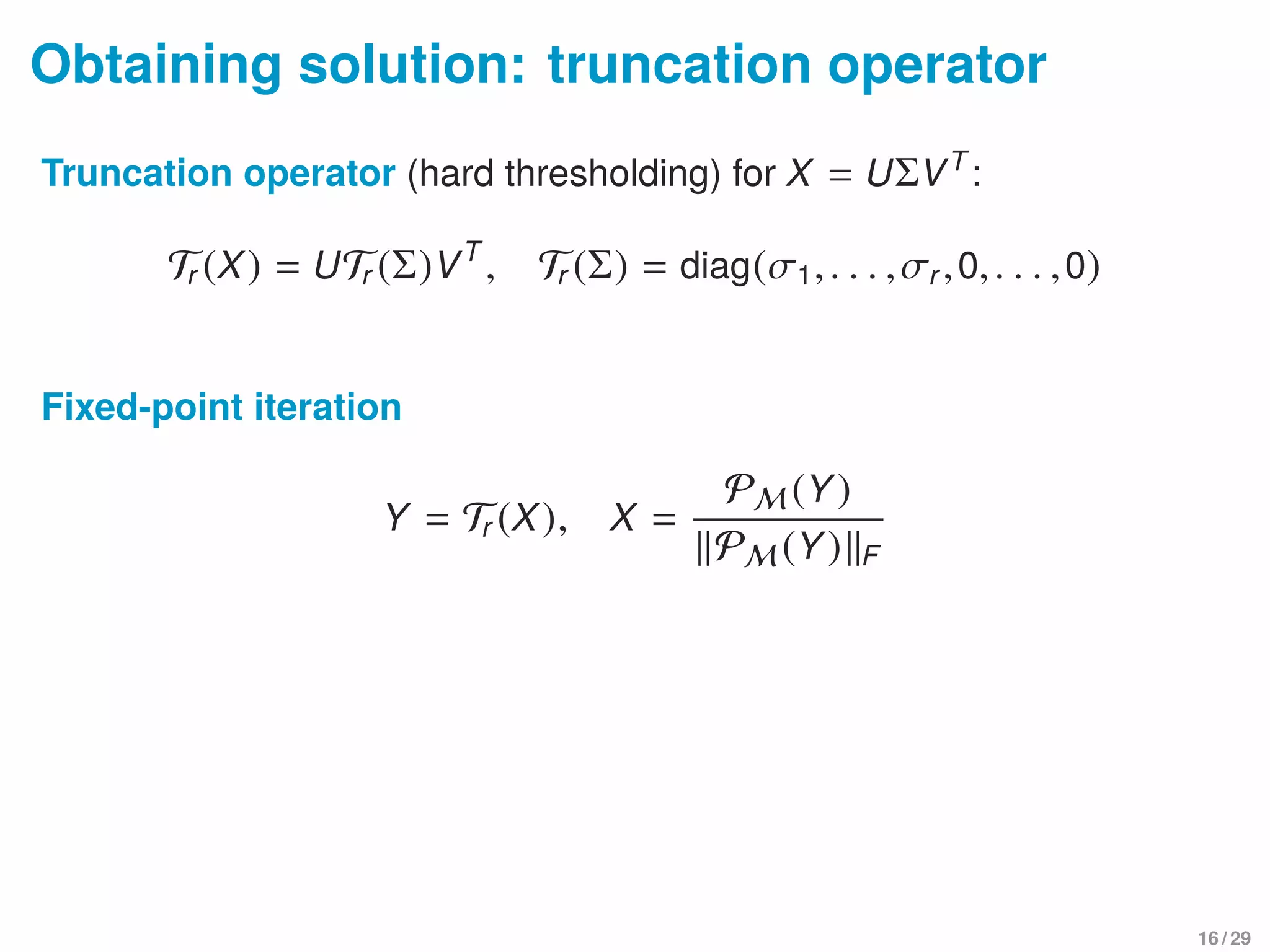

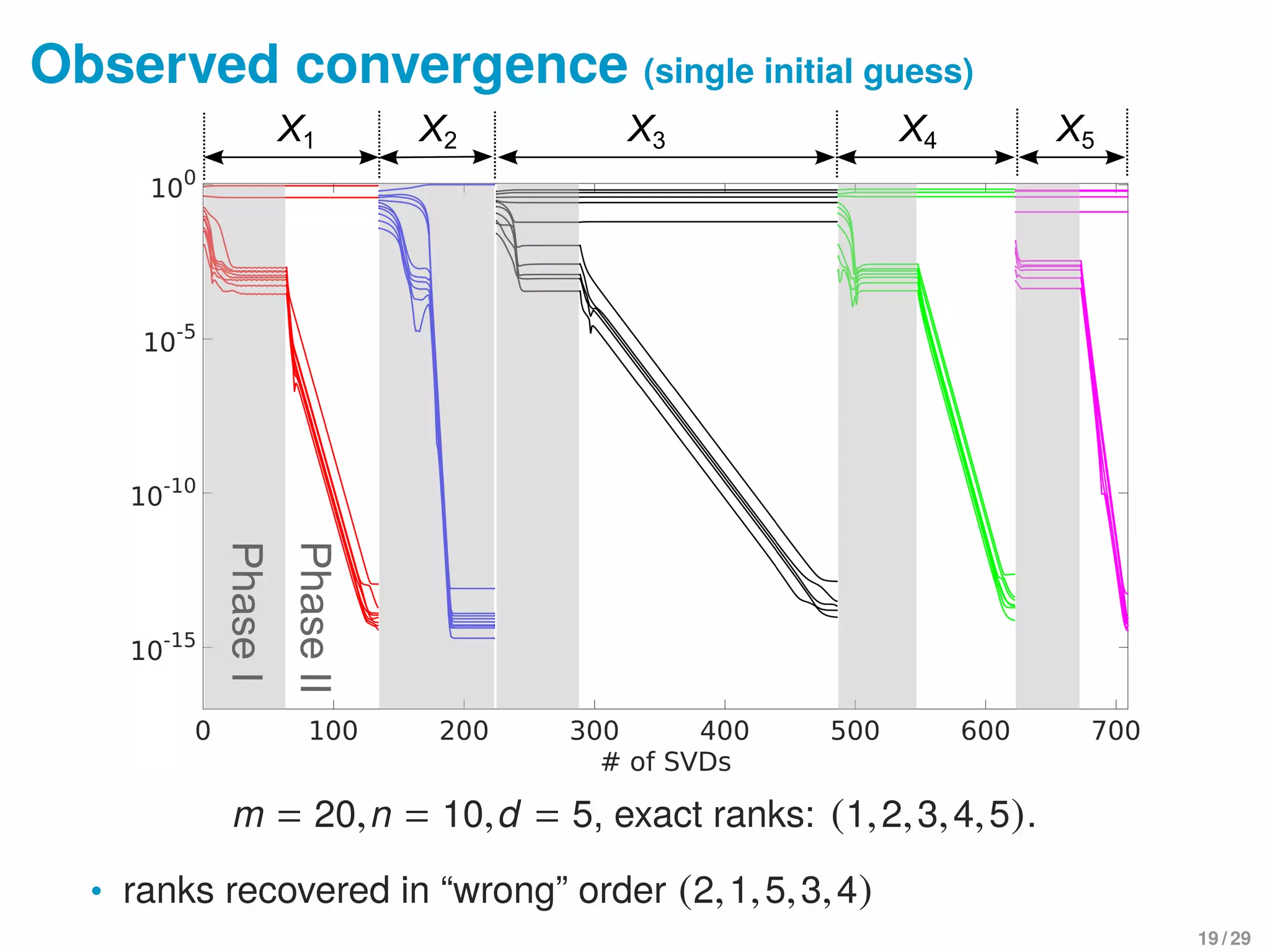

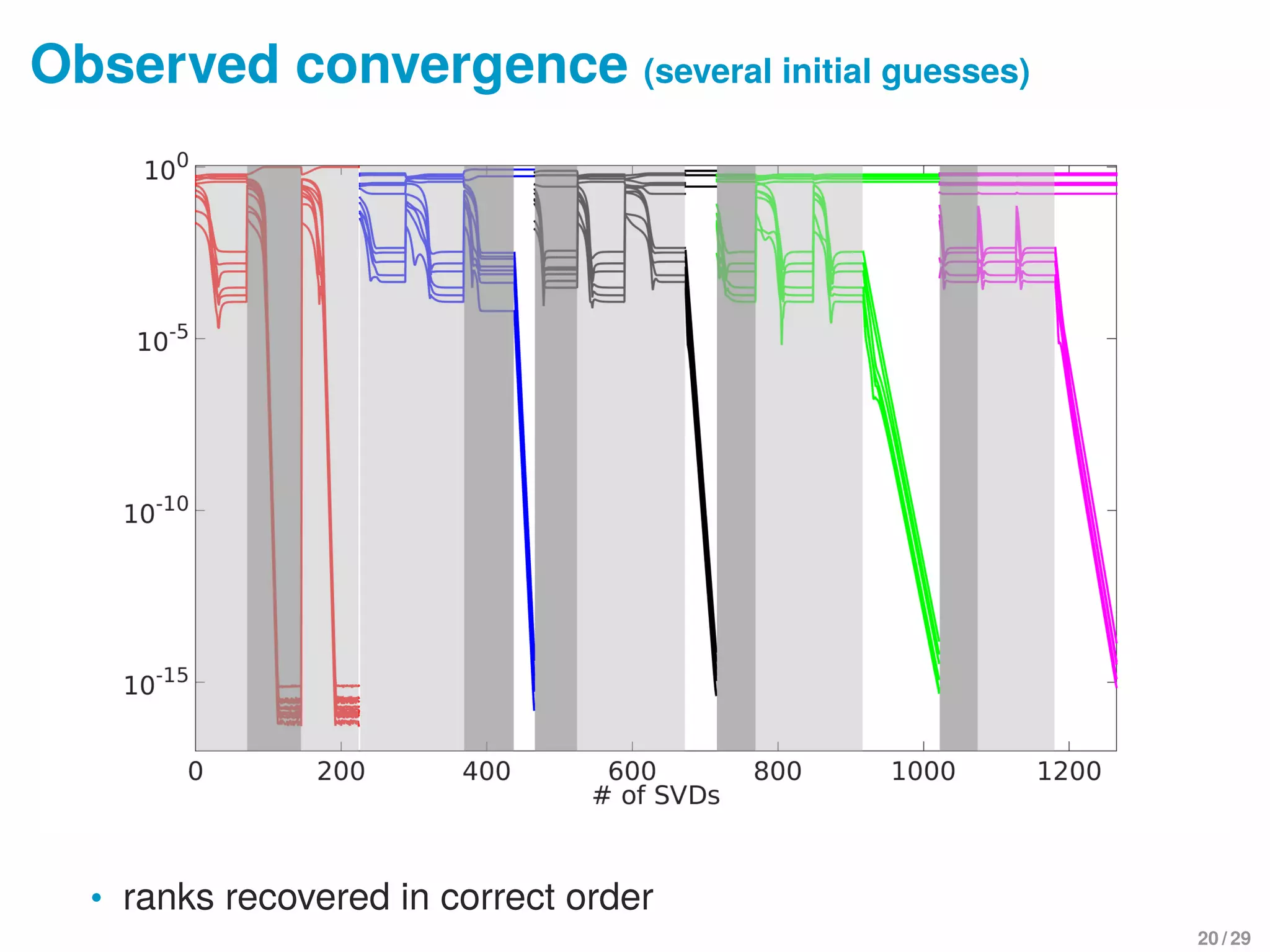

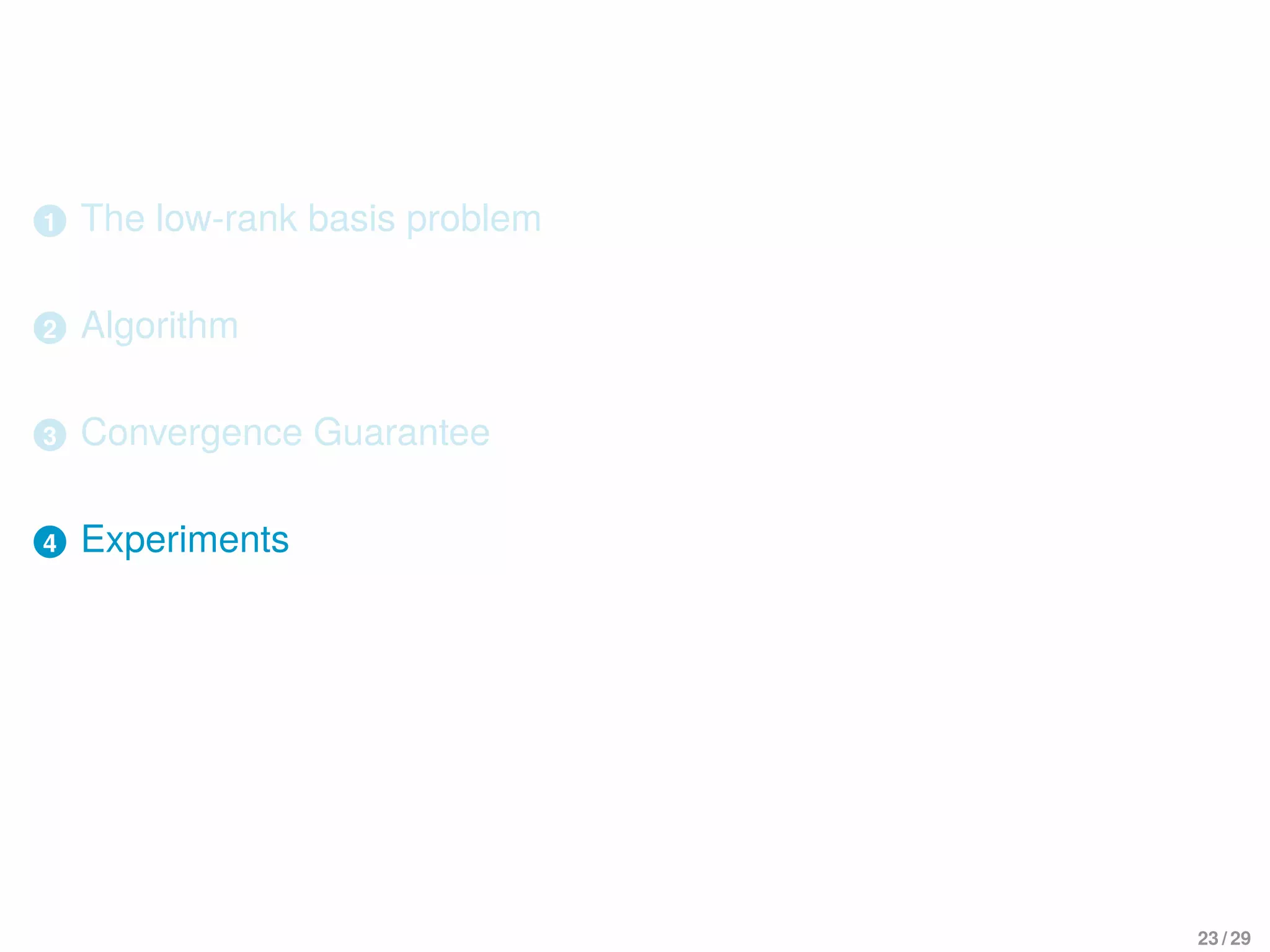

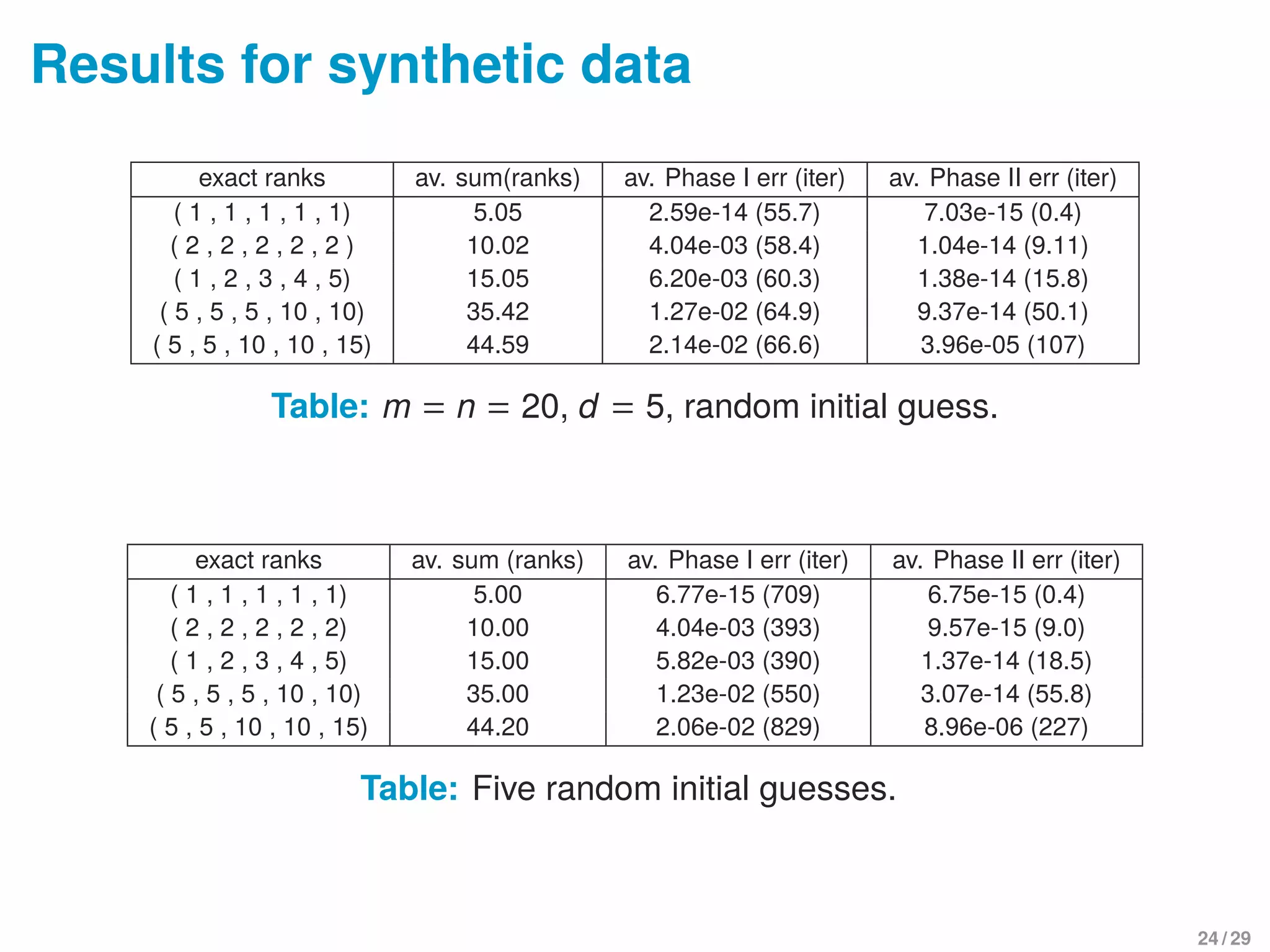

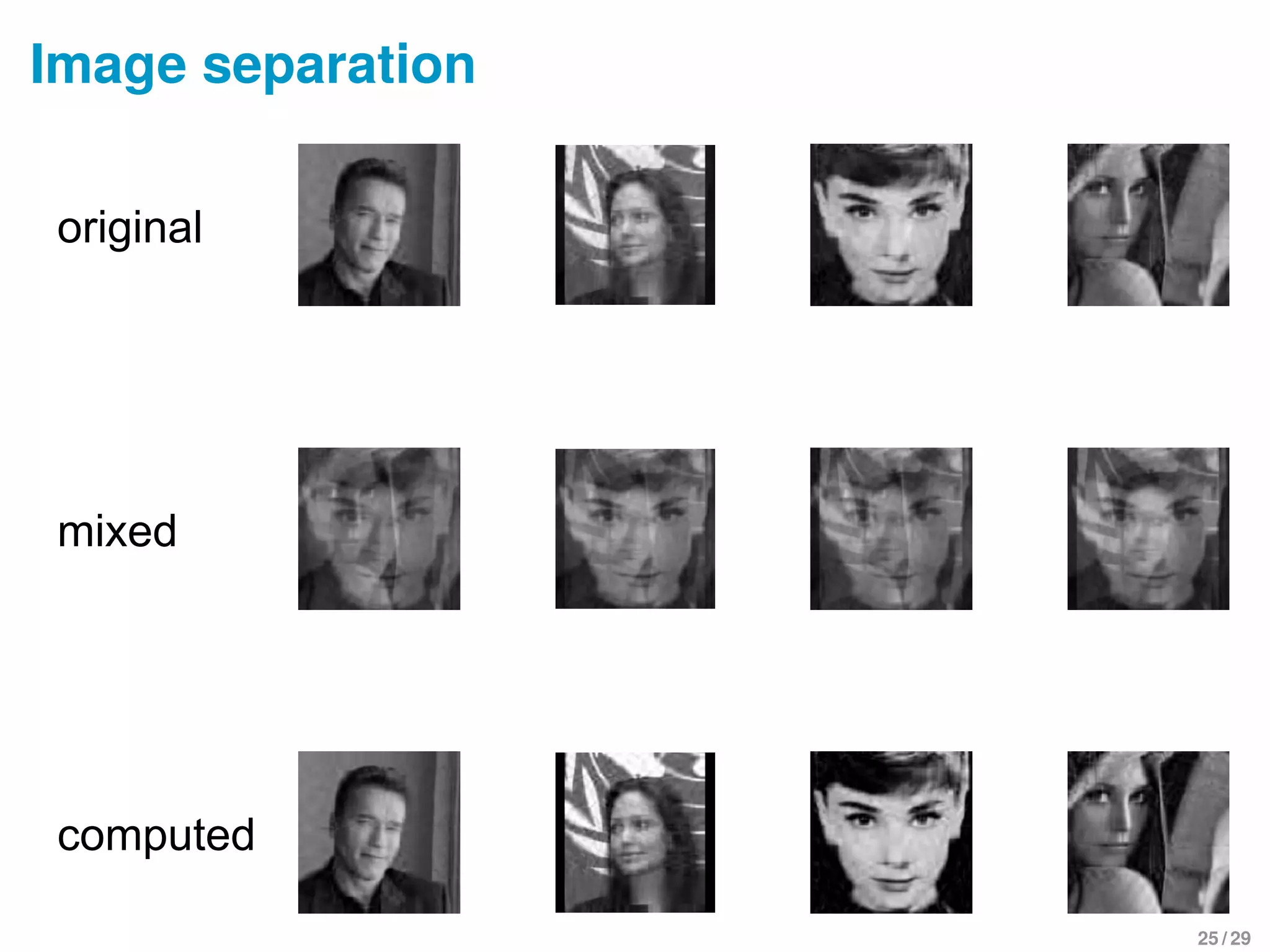

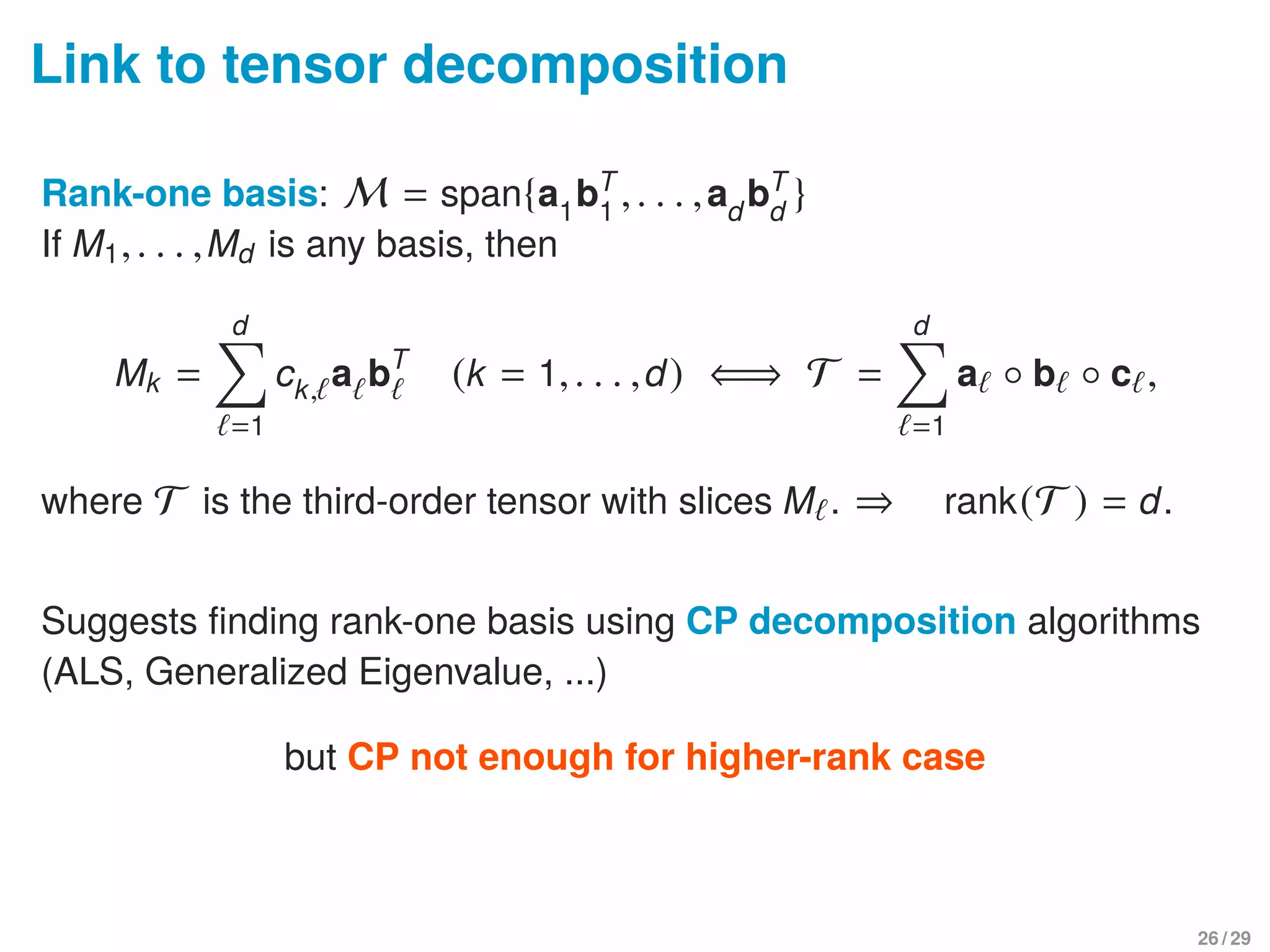

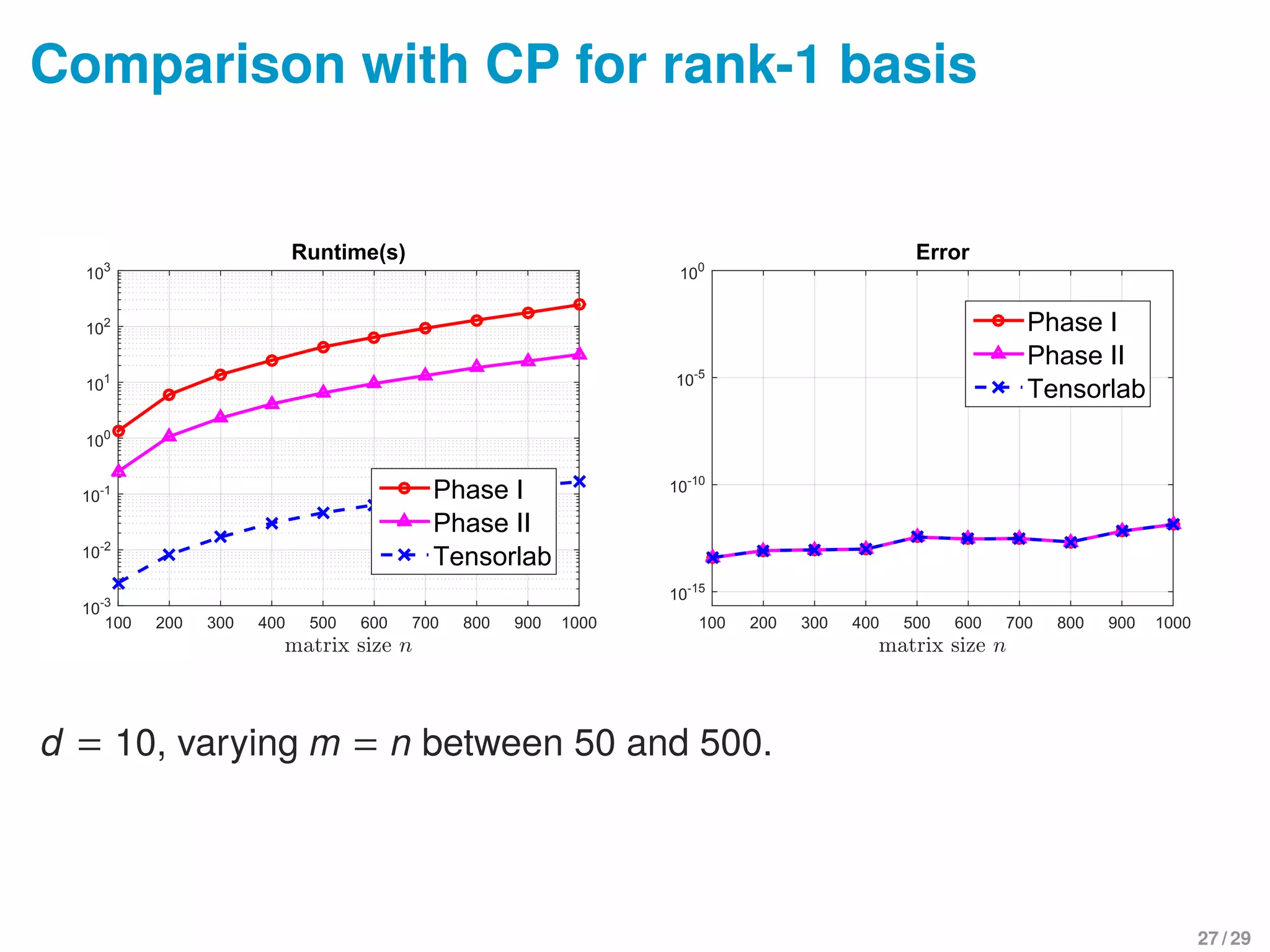

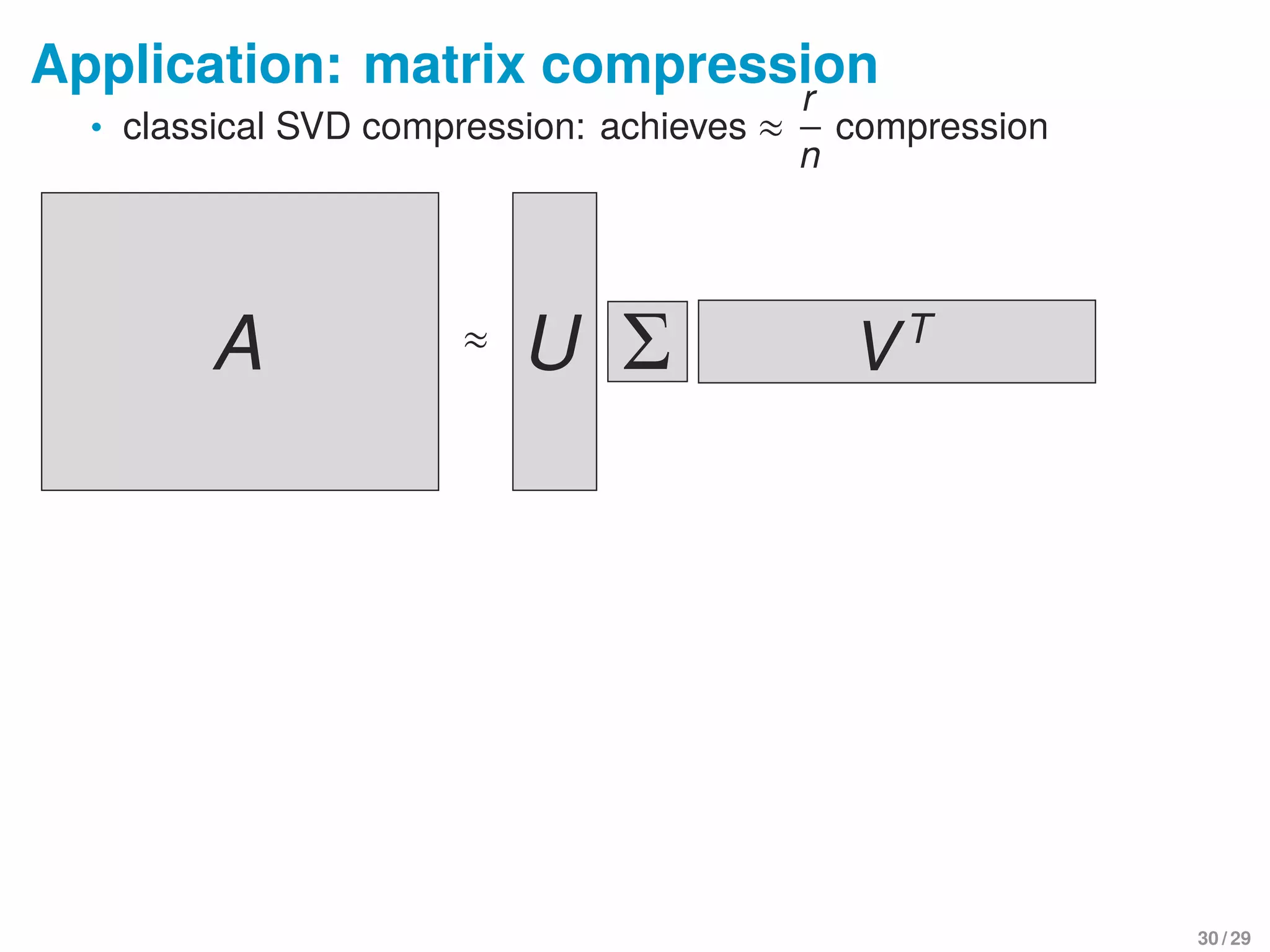

This document summarizes a presentation on finding low-rank bases for matrix subspaces. It introduces the low-rank basis problem, describes a greedy algorithm to solve it using two phases - rank estimation and alternating projection, and proves local convergence guarantees for the algorithm. Experimental results on synthetic and image data demonstrate the algorithm can recover known low-rank bases and separate mixed images. Comparisons are made to tensor decomposition methods for the special case of rank-1 bases.

![Scope

lowrank basis

sparse basis

(Coleman-Pothen 86)

basis problems

lowrank matrix

sparse vector

(Qu-Sun-Wright 14)

single element problems

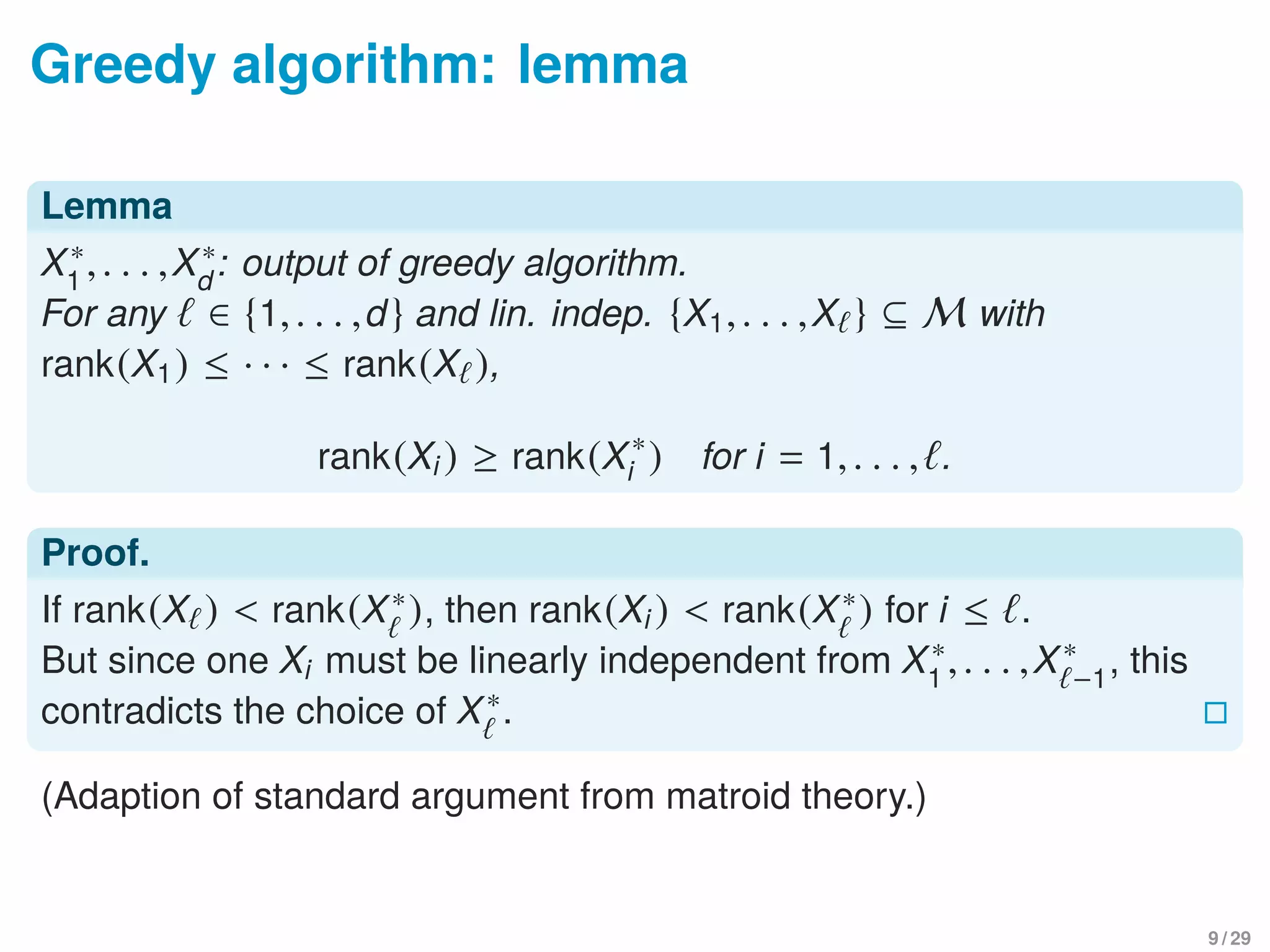

• sparse vector problem is NP-hard [Coleman-Pothen 1986]

5 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-7-2048.jpg)

![Scope

lowrank basis

sparse basis

(Coleman-Pothen 86)

basis problems

lowrank matrix

sparse vector

(Qu-Sun-Wright 14)

single element problems

• sparse vector problem is NP-hard [Coleman-Pothen 1986]

• Related studies: dictionary learning [Sun-Qu-Wright 14], sparse PCA

[Spielman-Wang-Wright],[Demanet-Hand 14]

5 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-8-2048.jpg)

![Greedy algorithm: justification

Theorem

X∗

1

,. . . ,X∗

d

: lin. indep. output of greedy algorithm. Then {X1,. . . ,X } is

of minimal rank iff

rank(Xi ) = rank(X∗

i ) for i = 1,. . . , .

In particular, {X∗

1

,. . . ,X∗} is of minimal rank.

• Analogous result for sparse basis problem in [Coleman, Pothen 1986]

10 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-14-2048.jpg)

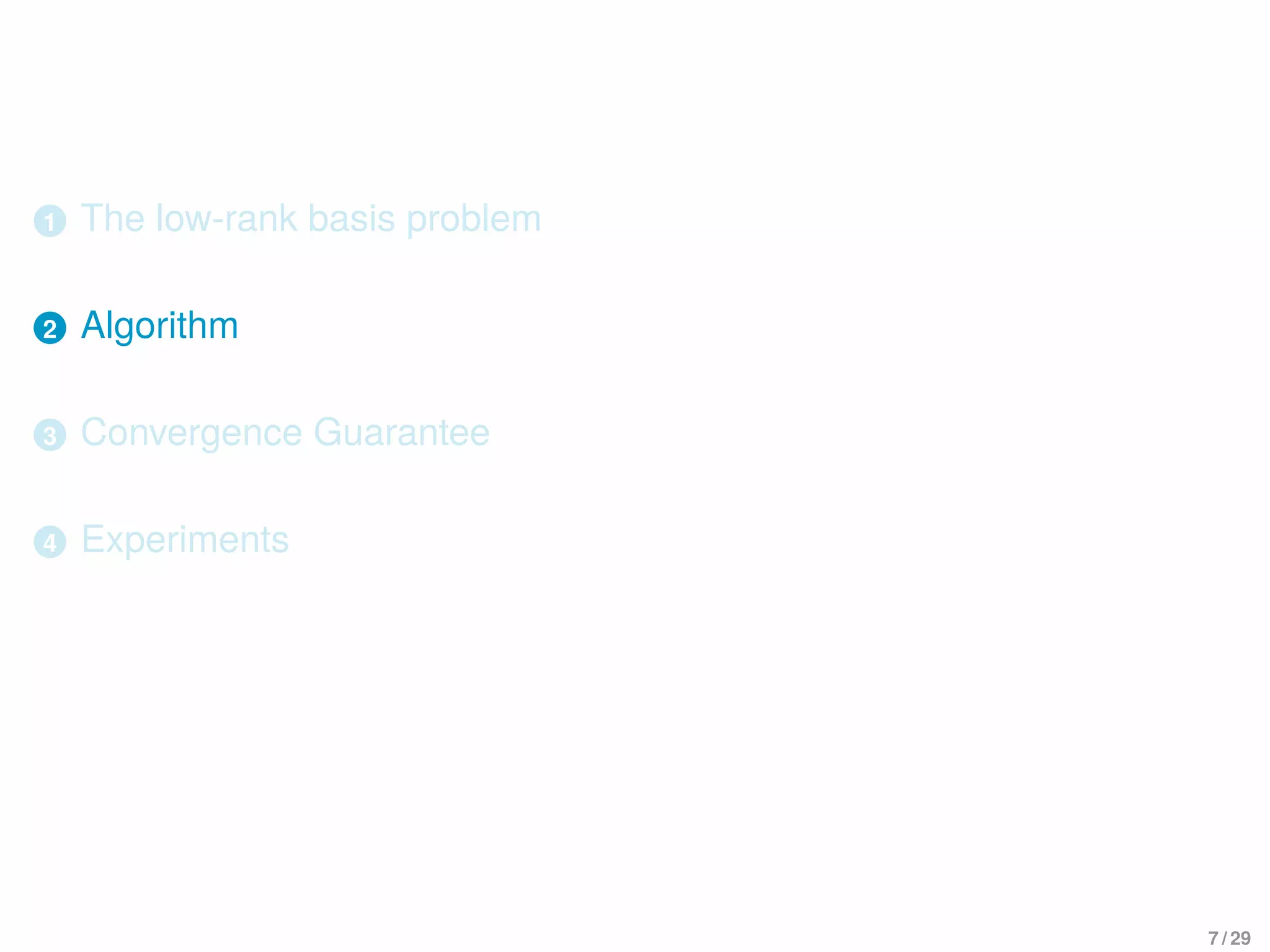

![Shrinkage operator

Shrinkage operator (soft thresholding) for X = UΣVT

:

Sτ(X) = USτ(Σ)VT

, Sτ(Σ) = diag(σ1 − τ,. . . ,σrank(X) − τ)+

Fixed-point iteration

Y = Sτ(X), X =

PM (Y)

PM (Y) F

Interpretation: [Cai, Candes, Shen 2010], [Qu, Sun, Wright @NIPS 2014]

block coordinate descent (a.k.a. alternating direction) for

minimize

X,Y

τ Y ∗ +

1

2

Y − X 2

F

subject to X ∈ M, and X F = 1,

[Qu, Sun, Wright @NIPS 2014]: analogous method for sparsest vector.

13 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-20-2048.jpg)

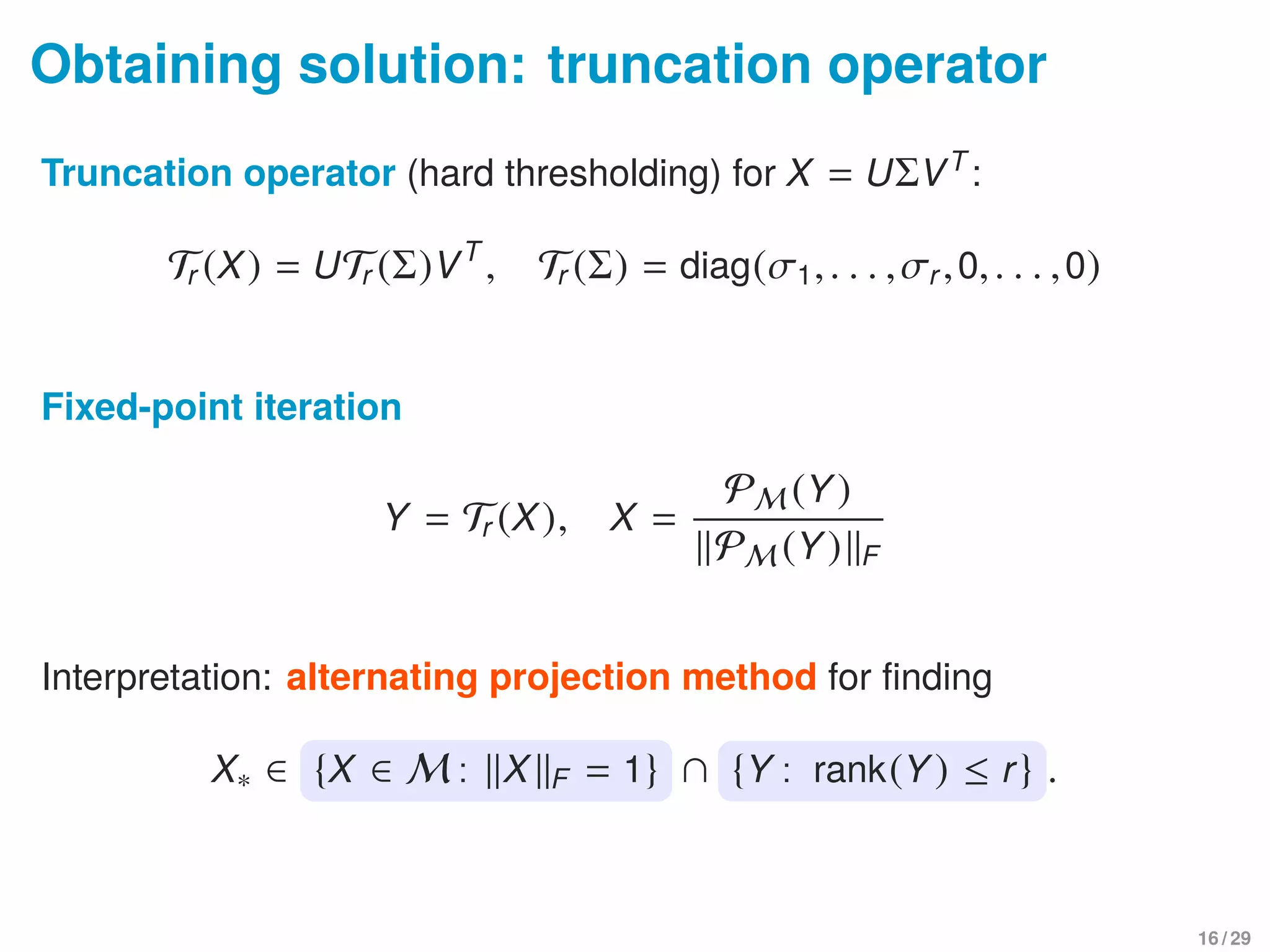

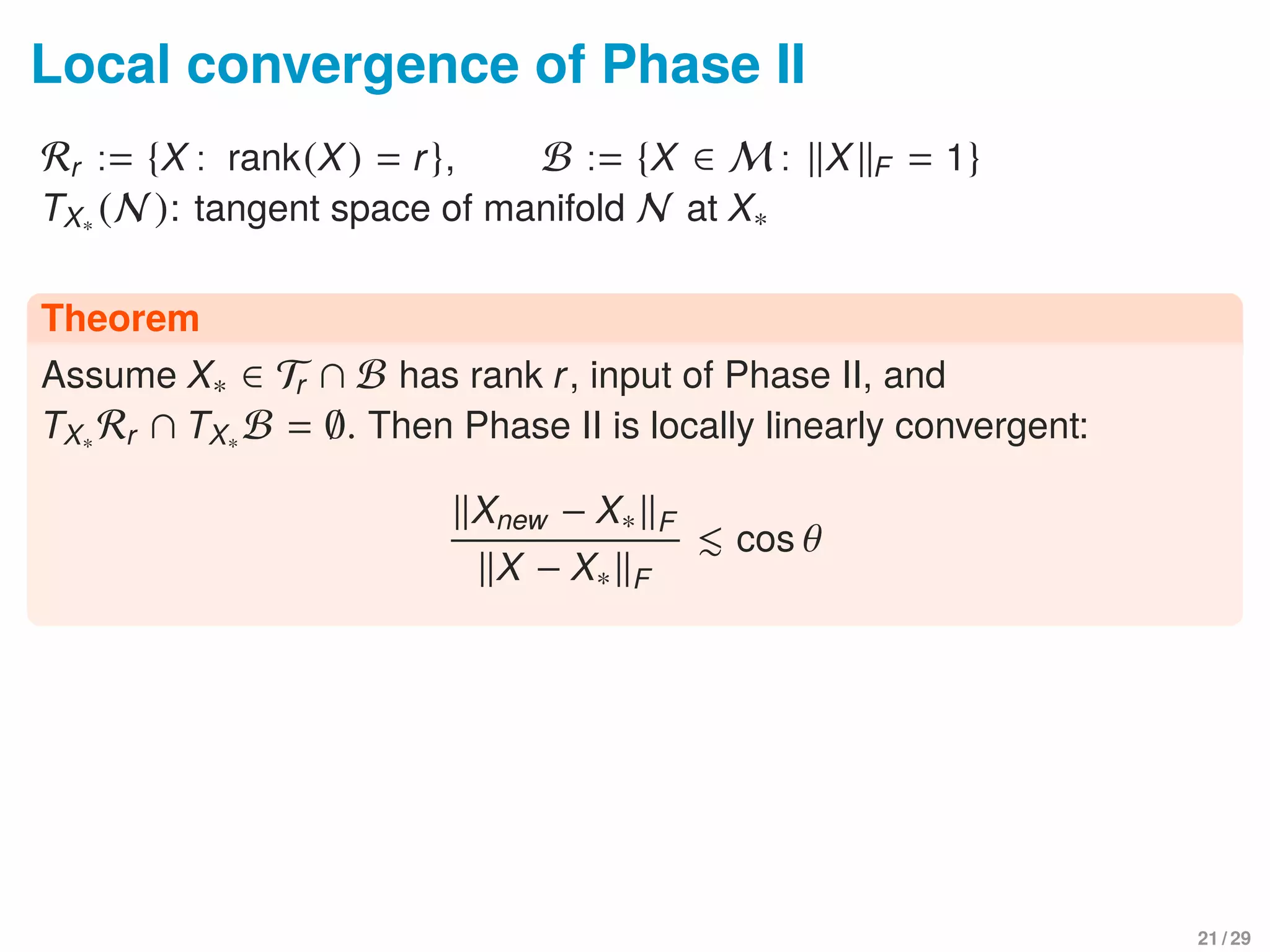

![Local convergence of Phase II

Rr := {X : rank(X) = r}, B := {X ∈ M : X F = 1}

TX∗ (N ): tangent space of manifold N at X∗

Theorem

Assume X∗ ∈ Tr ∩ B has rank r, input of Phase II, and

TX∗ Rr ∩ TX∗ B = ∅. Then Phase II is locally linearly convergent:

Xnew − X∗ F

X − X∗ F

cos θ

• Follows from a meta-theorem on alternating projections in

nonlinear optimization [Lewis, Luke, Malick 2009]

• We provide “direct” linear algebra proof

• Assumption holds if X∗ is isolated rank-r matrix in M

21 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-30-2048.jpg)

![Local convergence: intuition

X∗

TX∗ B

TX∗ Rr

cos θ ≈ 1√

2

X∗

TX∗ B

TX∗ Rr

cos θ ≈ 0.9

Xnew − X∗ F

X − X∗ F

≤ cos θ + O( X − X∗

2

F )

θ ∈ (0, π

2

]: subspace angle between TX∗ B and TX∗ Rr

cos θ = max

X∈TX∗ B

Y∈TX∗ Rr

| X,Y F |

X F Y F

.

22 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-31-2048.jpg)

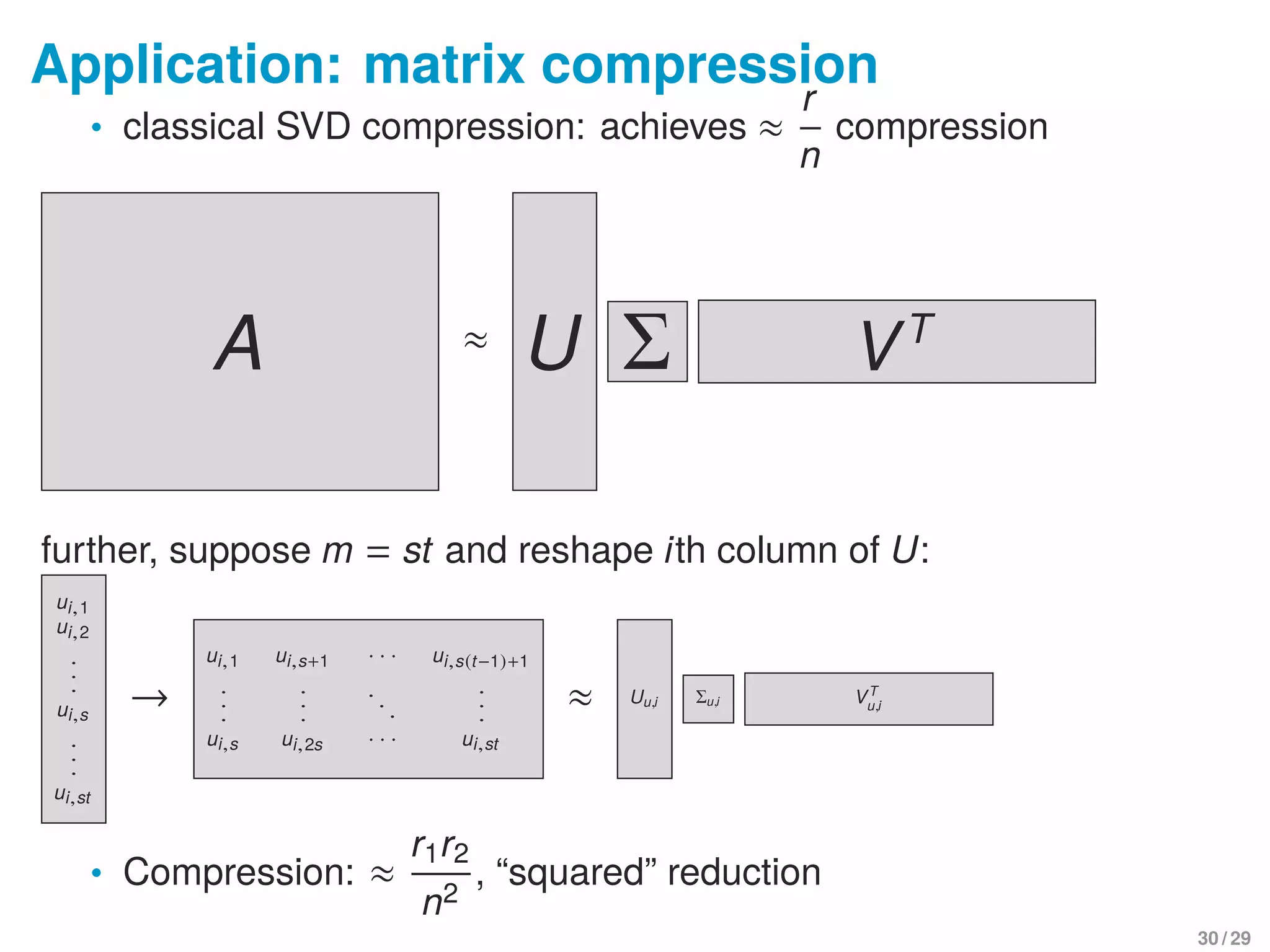

![Finding right “basis” for storage reduction

U = [U1,. . . ,Ur], ideally, each column Ui = [ui,1,ui,2,. . . ,ui,st]T

has

low-rank structure when matricized

ui,1

ui,2

.

.

.

ui,s

.

.

.

ui,st

→

ui,1 ui,s+1 · · · ui,s(t−1)+1

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

ui,s ui,2s · · · ui,st

≈ Uu,i VT

u,i for i = 1,. . . ,r

• More realistically: ∃ Q ∈ Rr×r

s.t. UQ has such property

⇒ finding low-rank basis for matrix subspace spanned by

mat(U1),mat(U2),. . . ,mat(Ur )

31 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-41-2048.jpg)

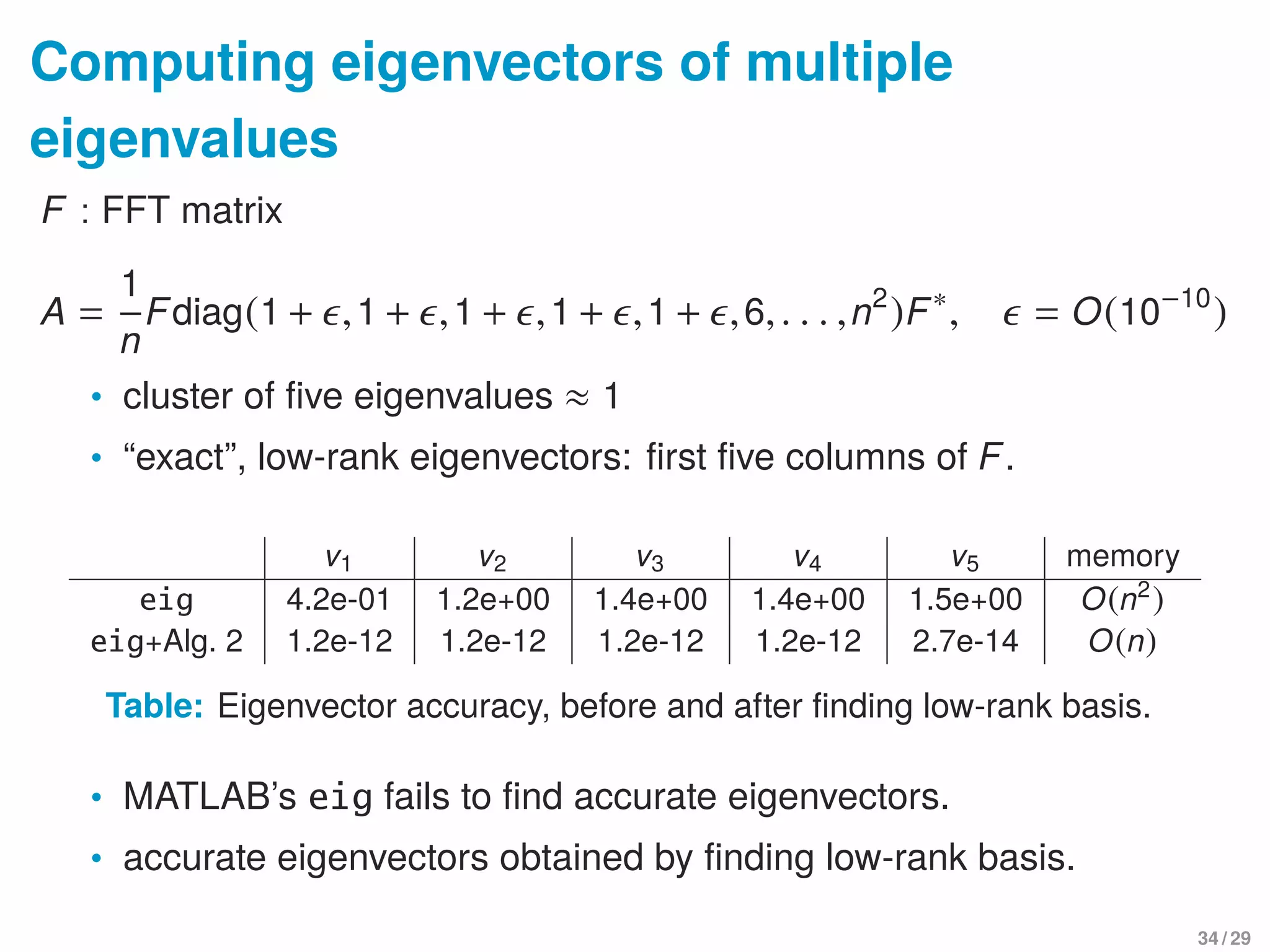

![Eigenvectors of multiple eigenvalues

A[x1,x2,. . . ,xk] = λ[x1,x2,. . . ,xk]

• eigenvector x for Ax = λx is not determined uniquely +

non-differentiable

• numerical practice: content with computing span(x1,x2)

extreme example: I, any vector is eigenvector!

• but perhaps

1

,

1

, . . .

1

is a “good” set of eigenvectors

• why? low-rank, low-memory!

33 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-43-2048.jpg)

![Linear algebra convergence proof

TX∗ Rr = [U∗ U⊥

∗ ]

A B

C 0

[V∗ V⊥

∗ ]T

. (1)

X − X∗ = E + O( X − X∗

2

F )

with E ∈ TX∗ B. Write E = [U∗ U⊥

∗ ][ A B

C D ][V∗ V⊥

∗ ]T

. By (1)

D 2

F

≥ sin2

θ · E 2

F

. ∃F,G orthogonal s.t.

X = FT Σ∗ + A 0

0 D

GT

+ O( E 2

F ).

Tr (X) − X∗ F =

A + Σ∗ 0

0 0

−

Σ∗ −B

−C CΣ−1

∗ B F

+ O( E 2

F )

=

A B

C 0 F

+ O( E 2

F ).

So

Tr (X) − X∗ F

X − X∗ F

=

E 2

F

− D 2

F

+ O( X − X∗

2

F

)

E F + O( X − X∗

2

F

)

≤ 1 − sin2

θ + O( X − X∗

2

F ) = cos θ + O( X − X∗

2

F )

36 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-46-2048.jpg)

![String theory problem

Given A1,. . . ,Ak ∈ Rm×n

, find ci ∈ R s.t.

rank(c1A1 + c2A2 + · · · + ckAk ) < n

A1 A2 . . . Ak Q = 0, Q = [q1,. . . ,qnk−m]

• finding null vector that is rank-one when matricized

• ⇒ Lowest-rank problem from mat(q1),. . . ,mat(qnk−m) ∈ Rn×k

when rank= 1

• slow (or non-)convergence in practice

• NP-hard? probably.. but unsure (since special case)

38 / 29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slide-150726130623-lva1-app6891/75/The-low-rank-basis-problem-for-a-matrix-subspace-48-2048.jpg)