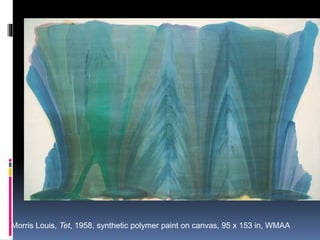

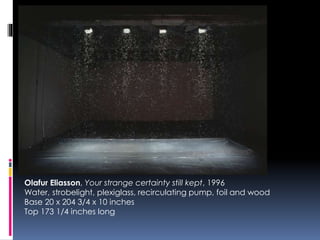

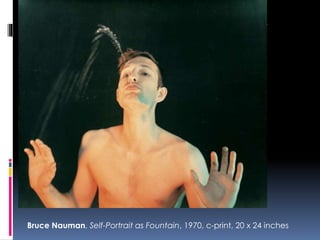

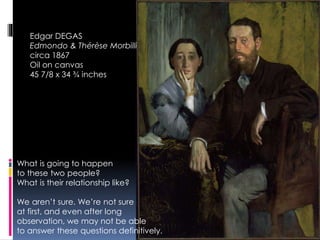

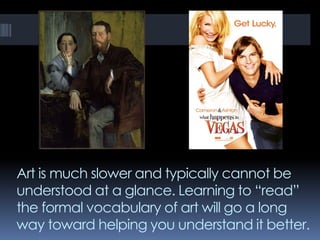

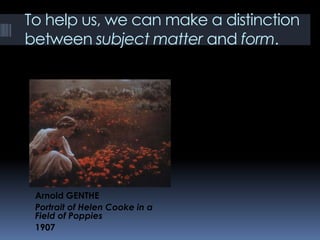

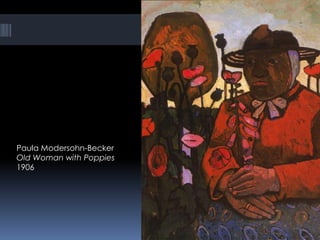

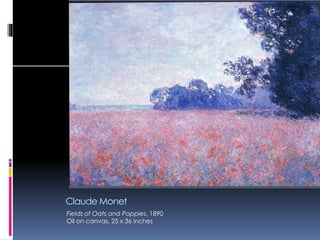

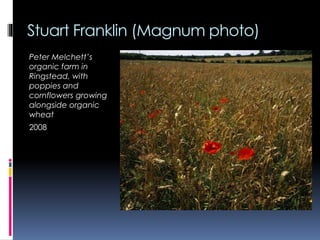

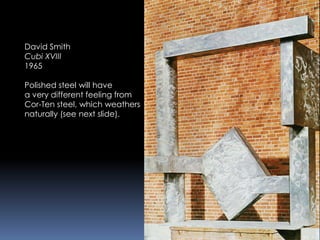

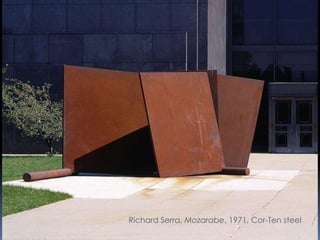

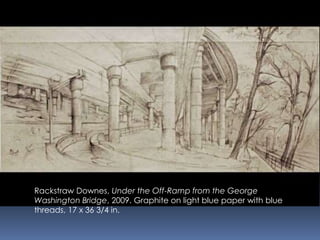

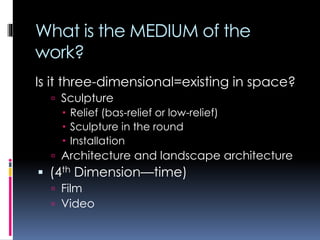

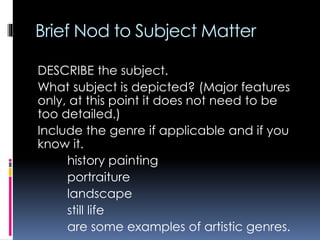

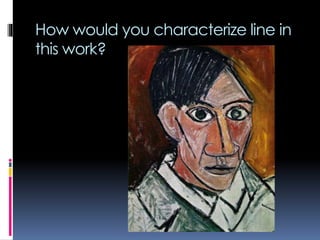

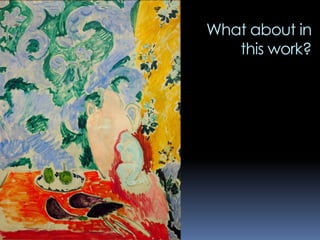

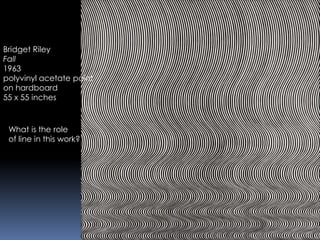

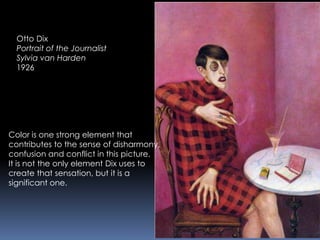

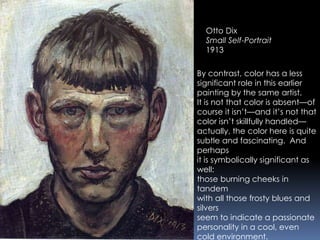

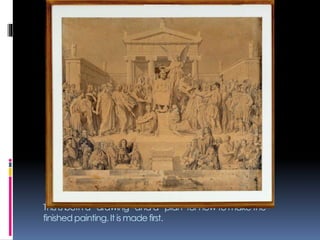

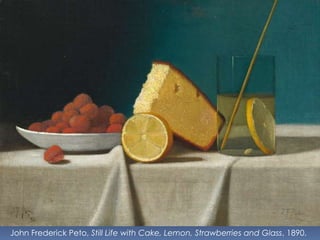

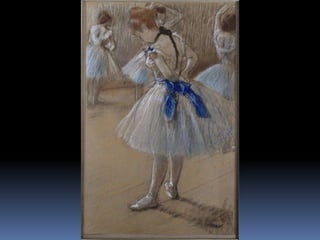

This document provides guidance on experiencing art to its fullest. It discusses experiencing the effects a work has on you through sight and feelings. It then suggests accounting for these effects through formal analysis of how the work is structured to achieve certain impacts. Formal analysis involves identifying the materials, medium, subject matter, composition, use of line, and role of color. Understanding these formal elements can help explain how a work creates certain feelings or responses. The goal is a richer experience and understanding of art.