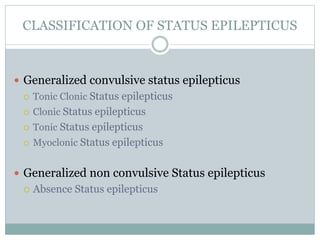

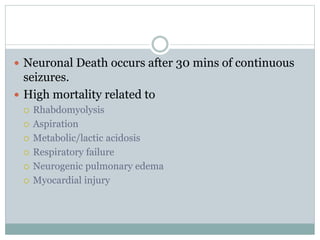

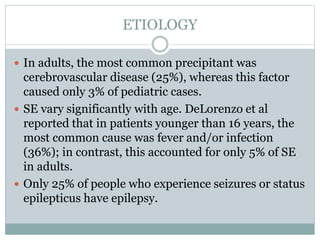

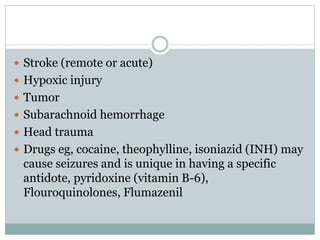

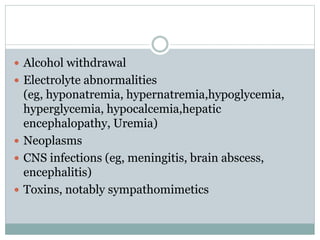

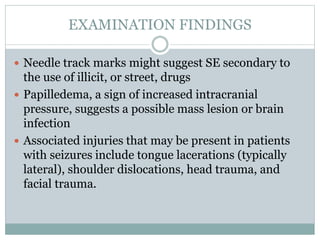

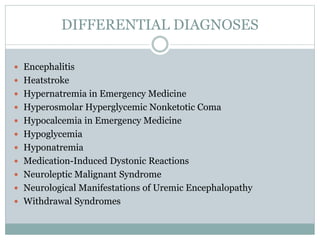

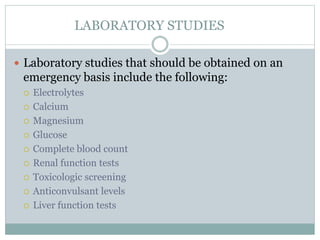

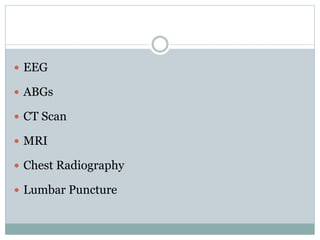

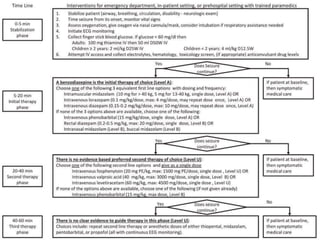

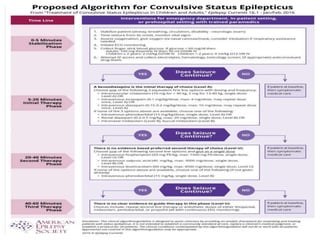

This document discusses status epilepticus, which is defined as prolonged or repeated seizures without recovery between seizures. It classifies status epilepticus, explores its pathophysiology and etiology, and outlines its presentation, differential diagnosis, workup, and management. Status epilepticus results from either failed seizure termination mechanisms or initiation of mechanisms leading to prolonged seizures. It can cause neuronal death or injury if not promptly treated. Management involves initial treatment with benzodiazepines followed by anti-seizure medications like fosphenytoin or anesthetic doses if seizures persist over 40 minutes.