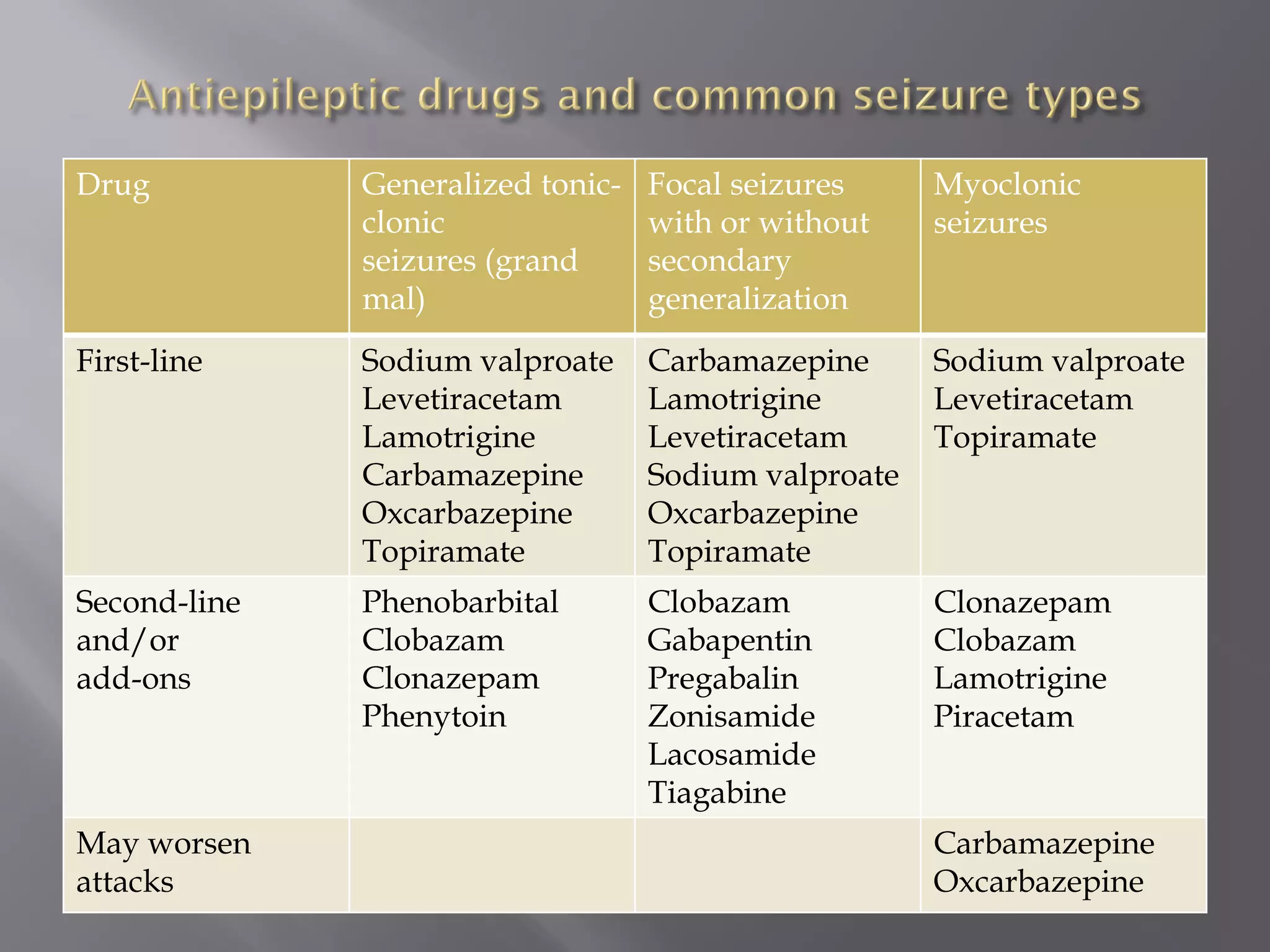

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures resulting from sudden neuronal discharges in the brain, with a prevalence of 0.7-0.8%, particularly affecting individuals at the extremes of age. Seizures can be categorized into partial, generalized, and unclassified types, each with distinct clinical patterns and potential causes, including structural brain lesions and metabolic disorders. The diagnosis of epilepsy is primarily clinical, and treatment often includes antiepileptic drugs to manage seizures and minimize recurrence.