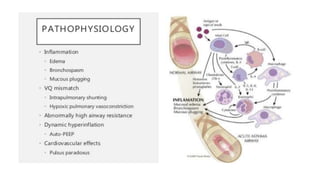

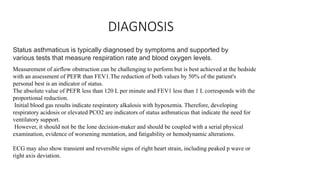

Status asthmaticus is an acute severe asthma attack that does not improve with usual bronchodilator treatment. It is characterized by hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and respiratory failure. Triggers include respiratory infections, stress, pollution, and poorly controlled asthma. Diagnosis is made through symptoms, peak flow measurements, and blood gases showing respiratory acidosis. Treatment involves nebulized bronchodilators, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and noninvasive ventilation or intubation. Patients are monitored until symptoms and lung function improve before discharge with medication and follow-up.