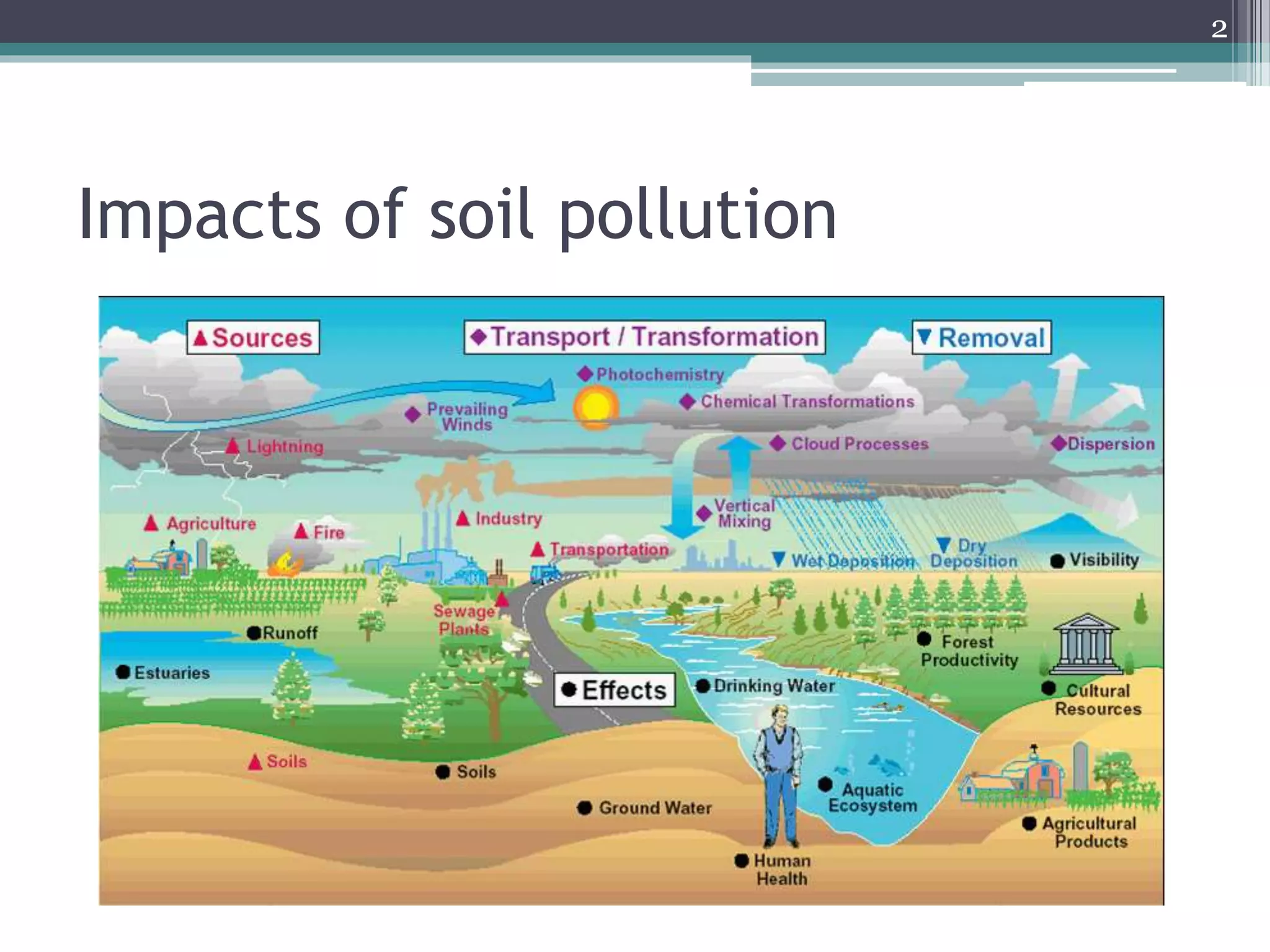

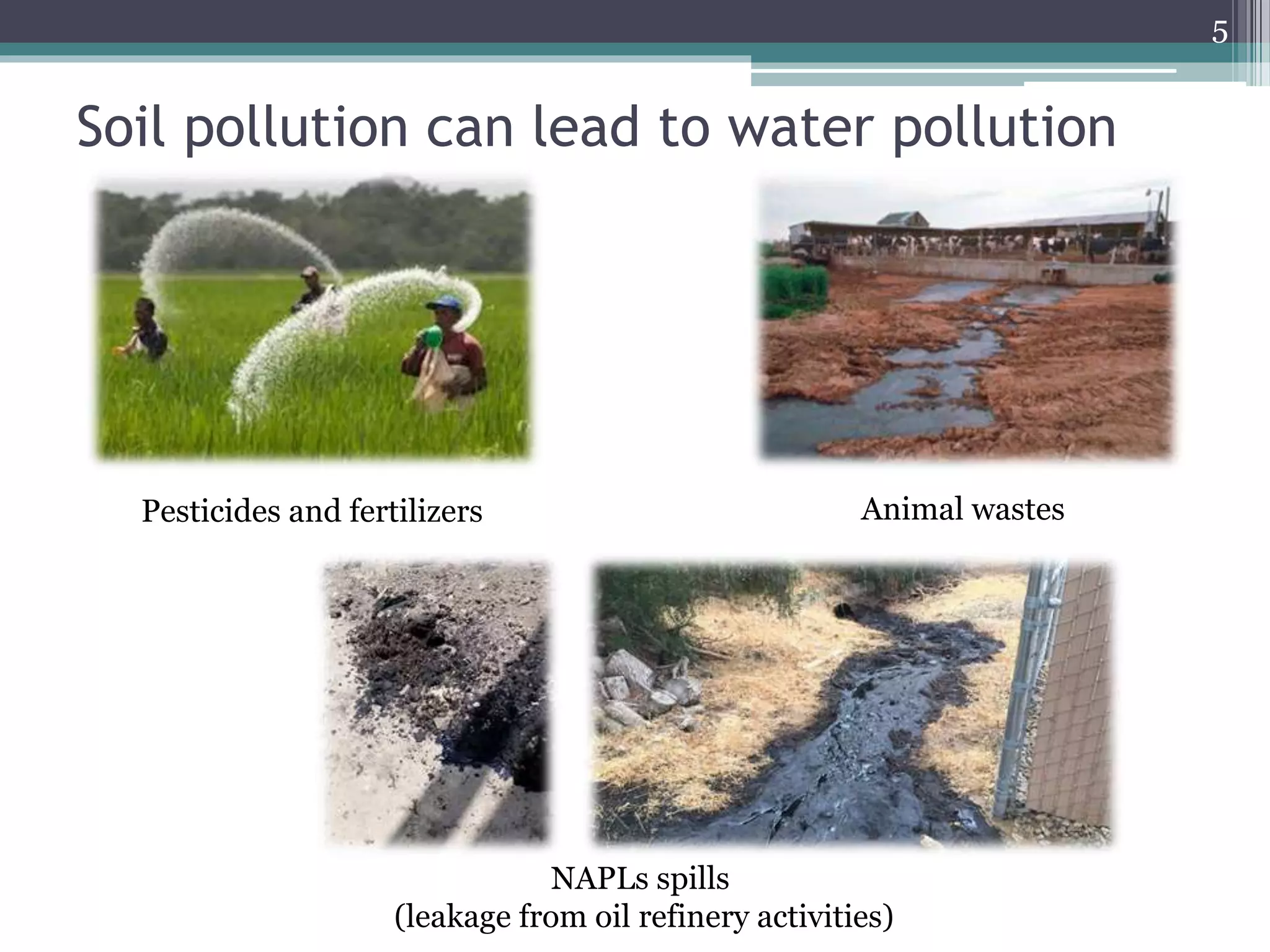

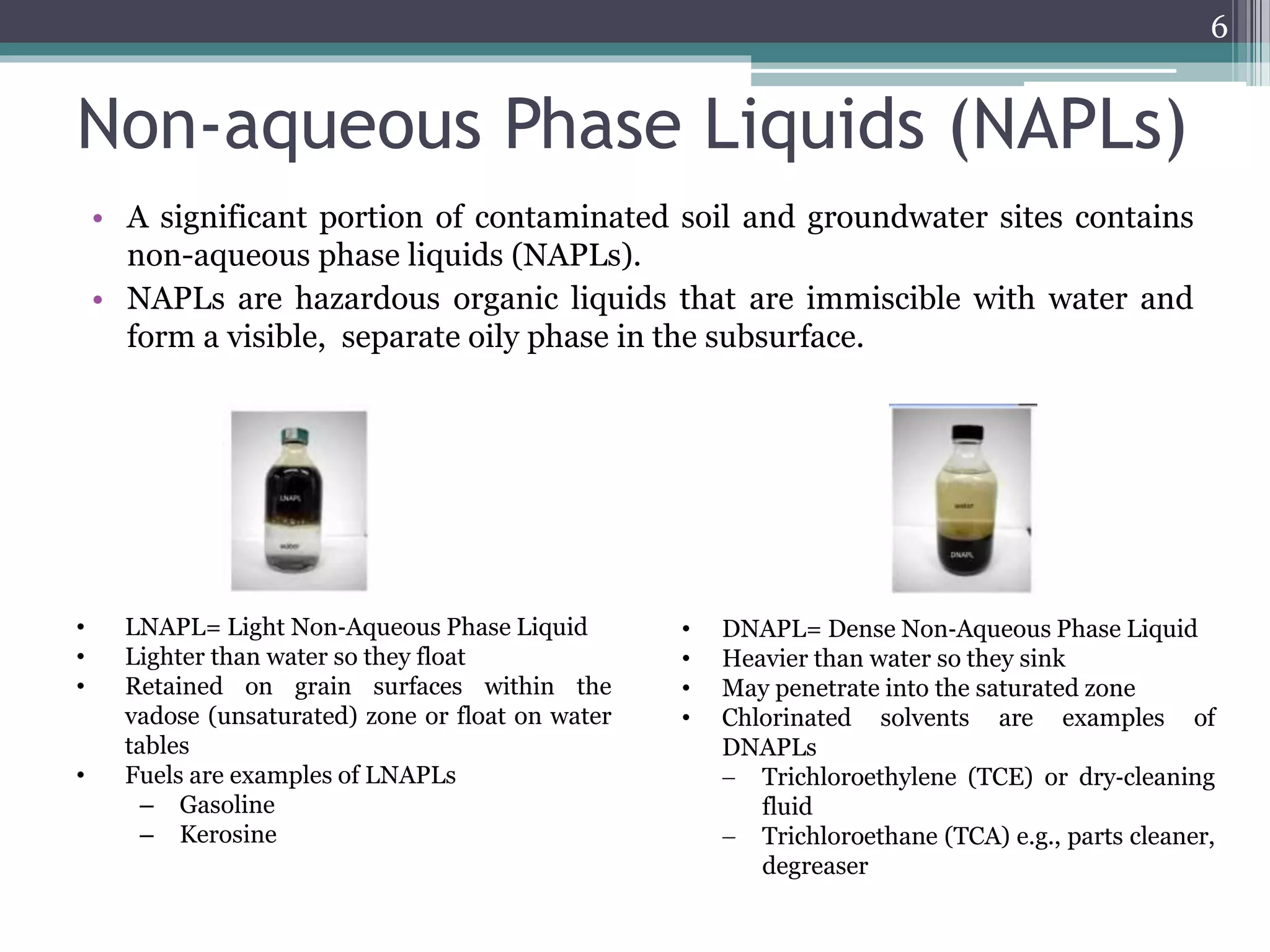

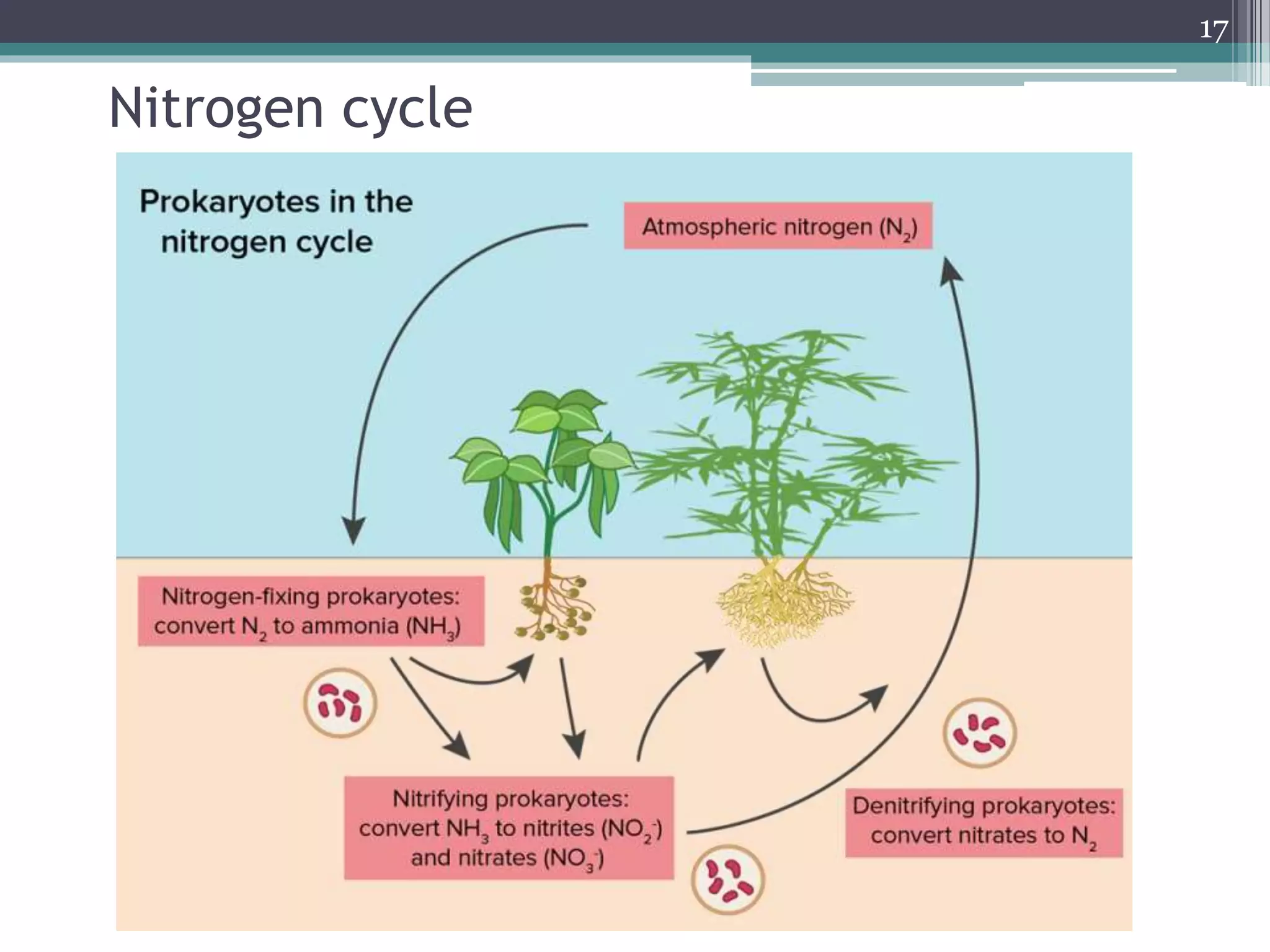

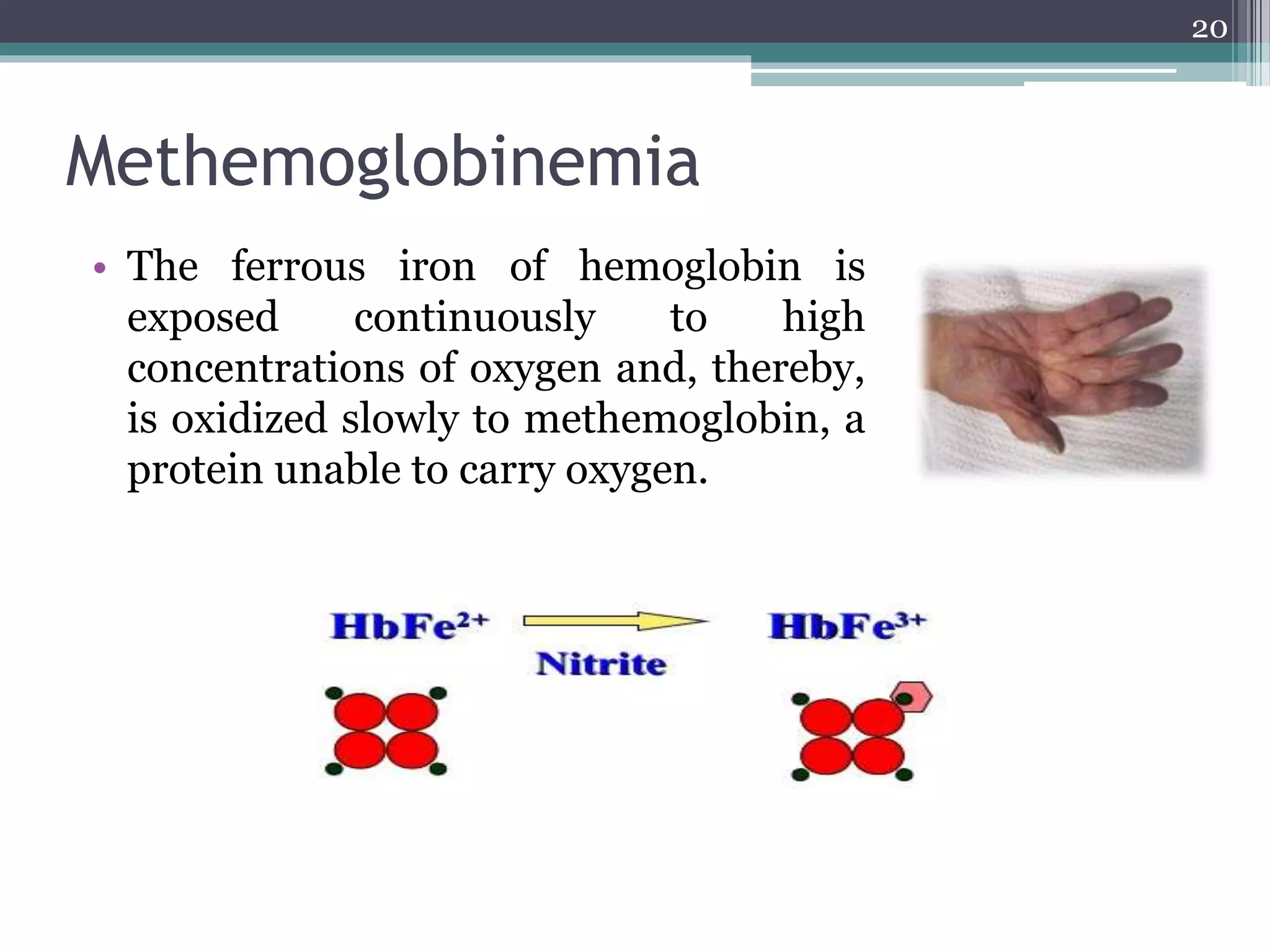

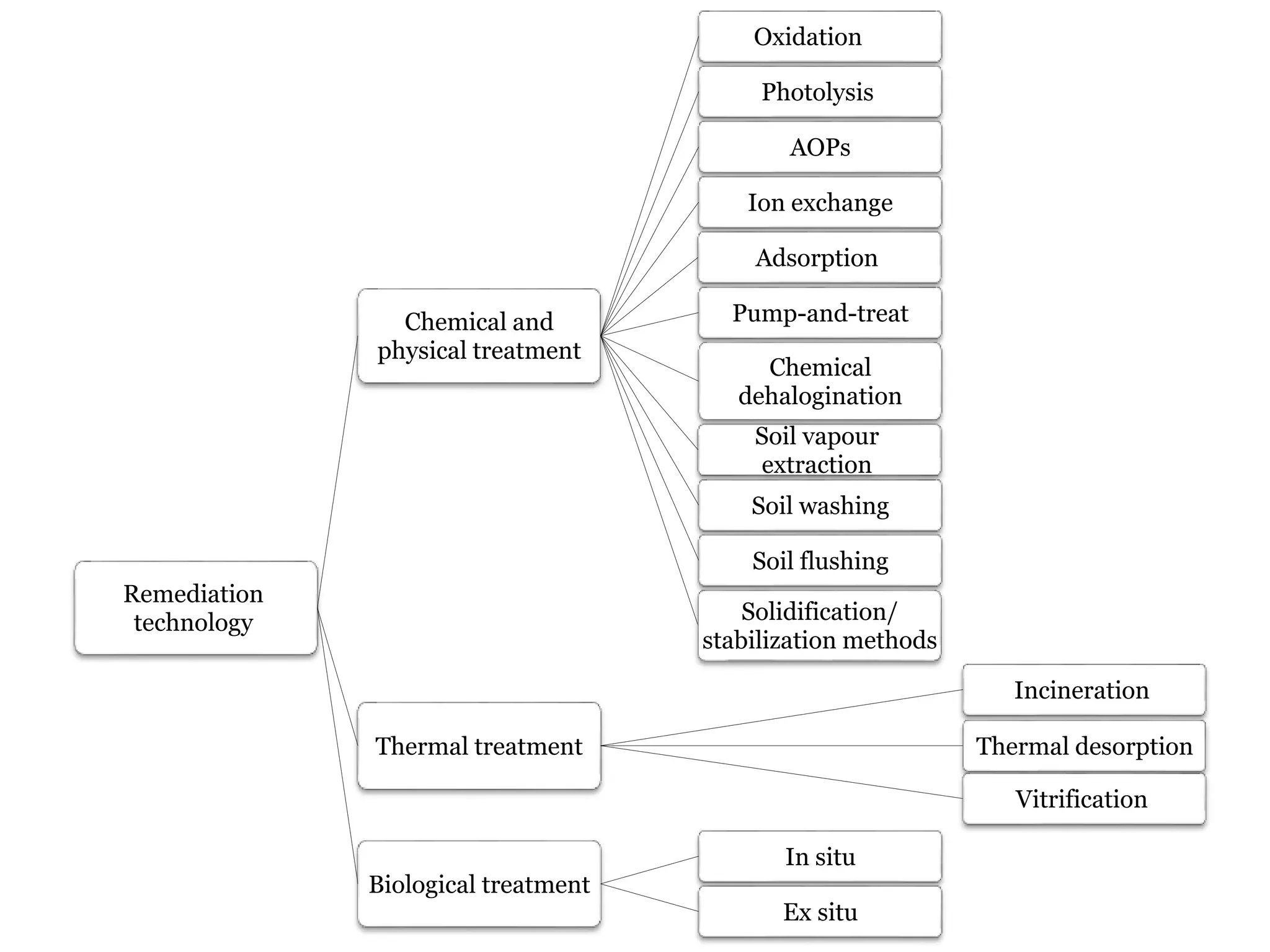

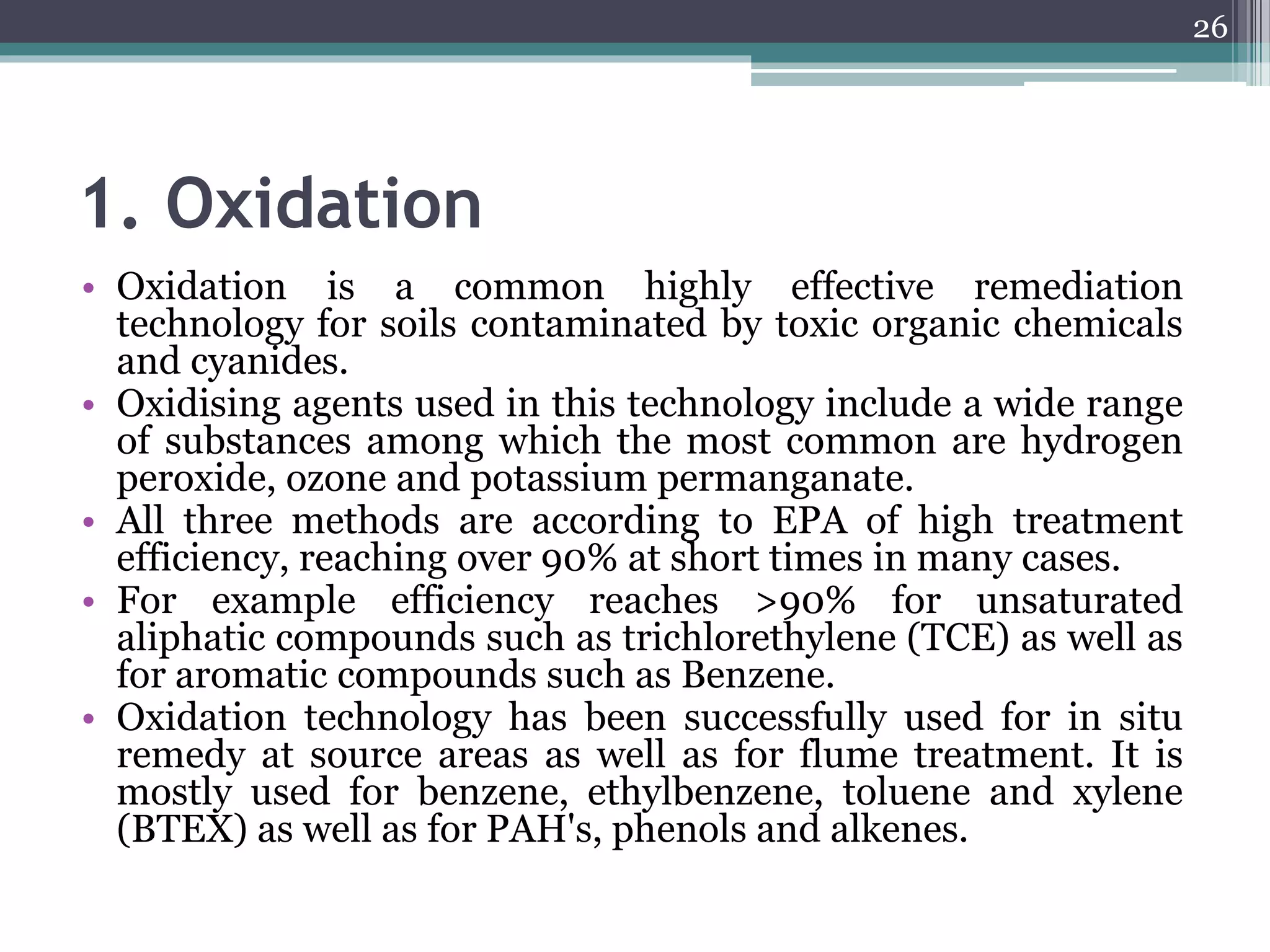

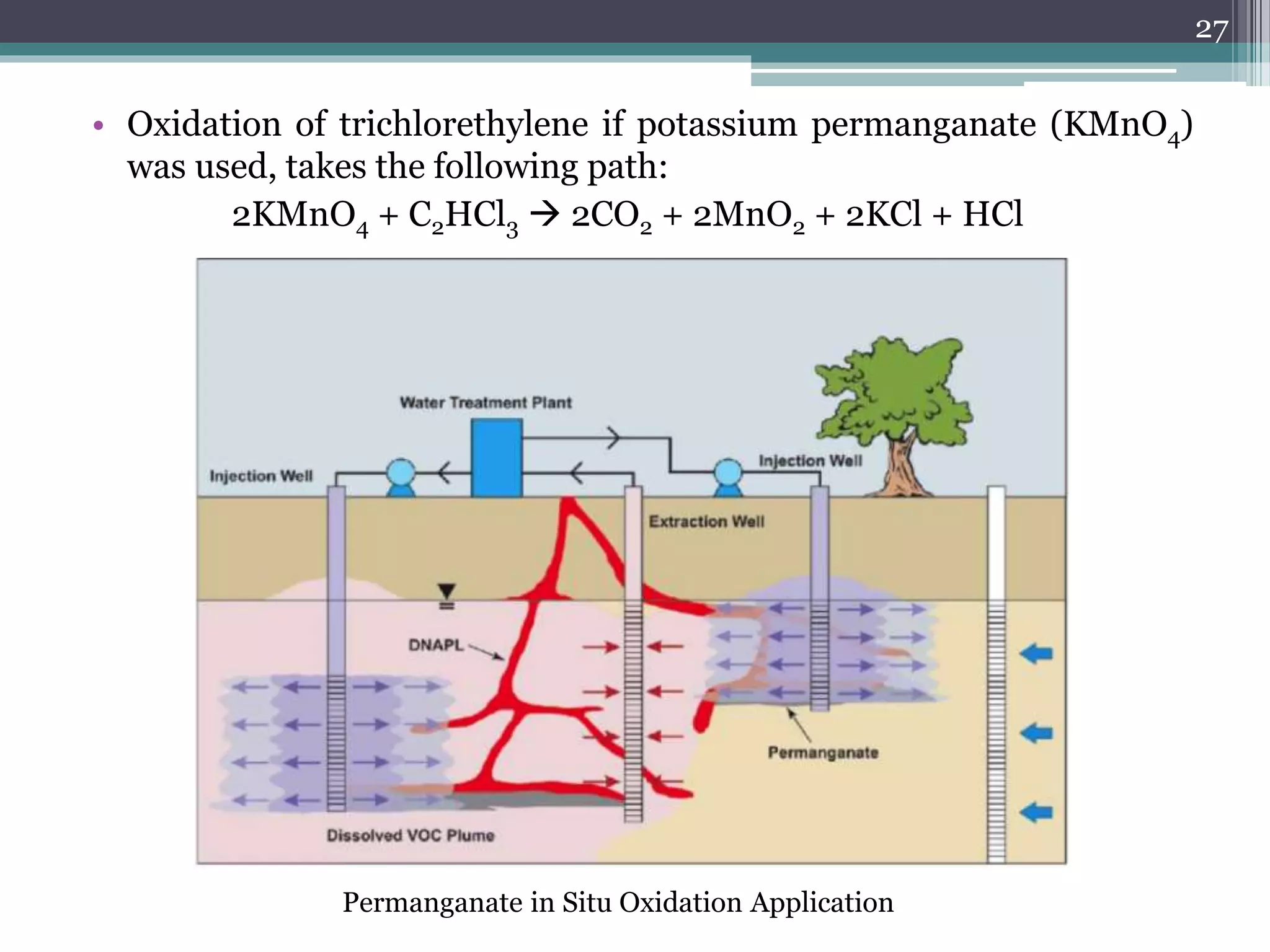

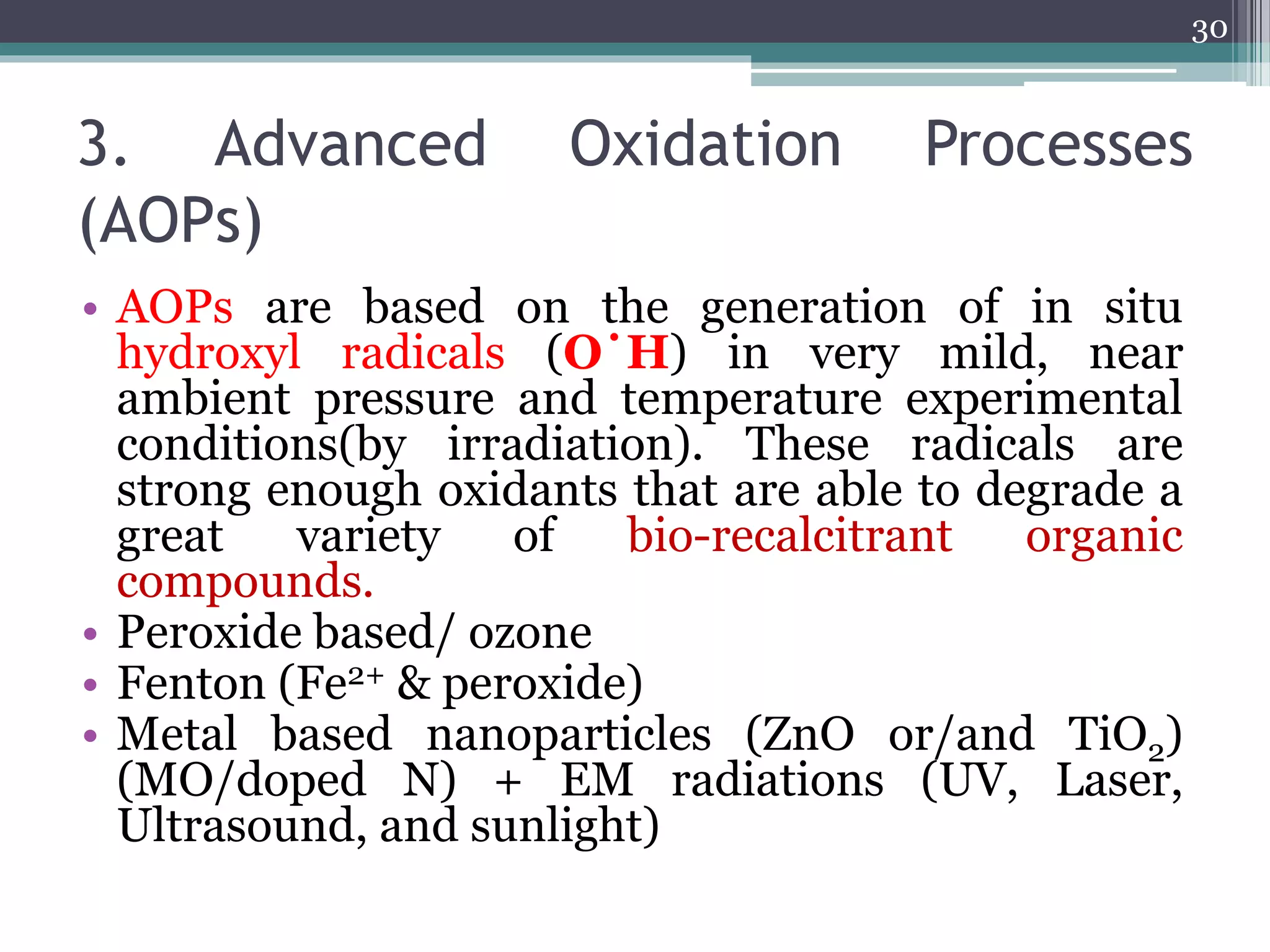

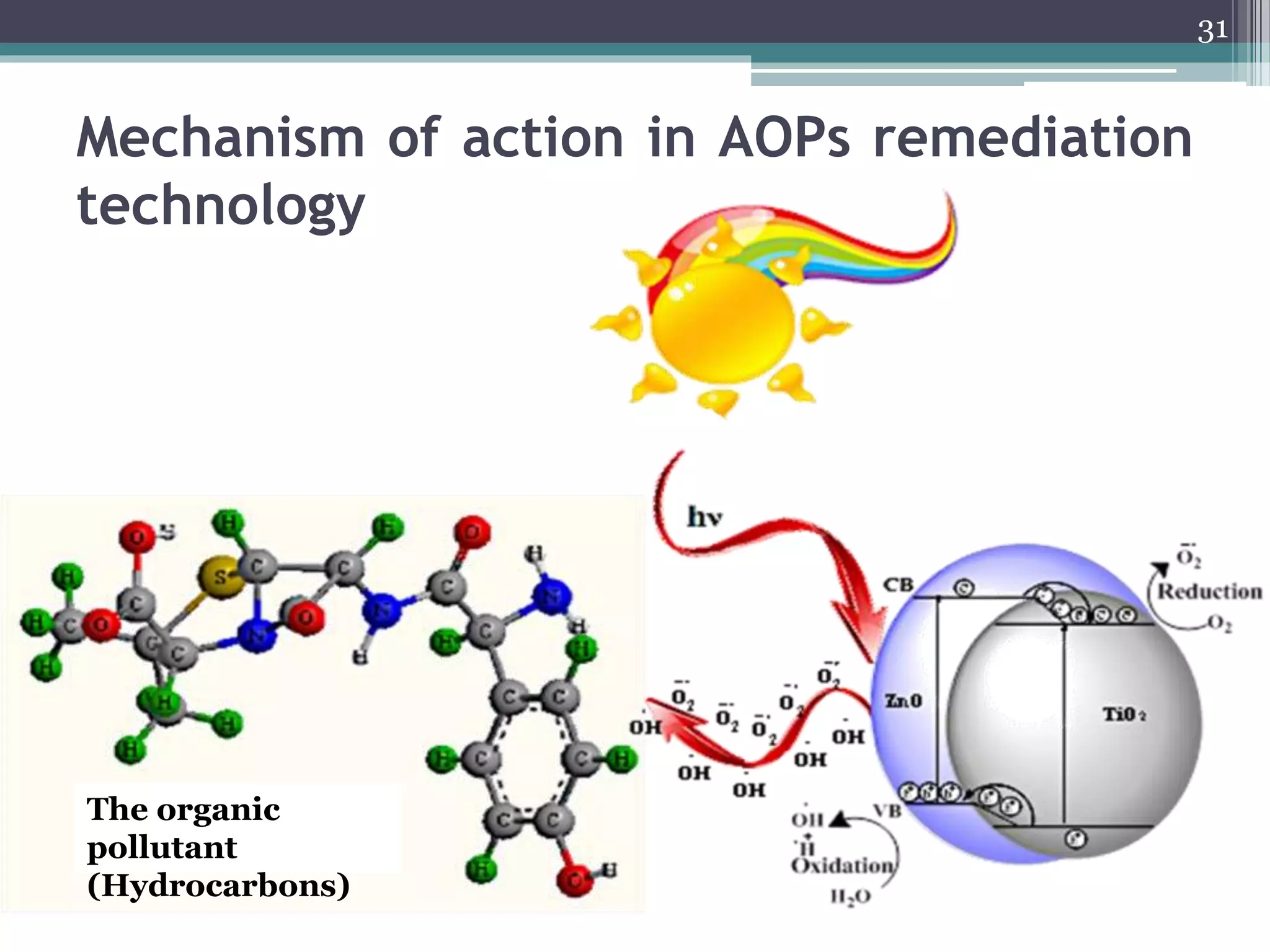

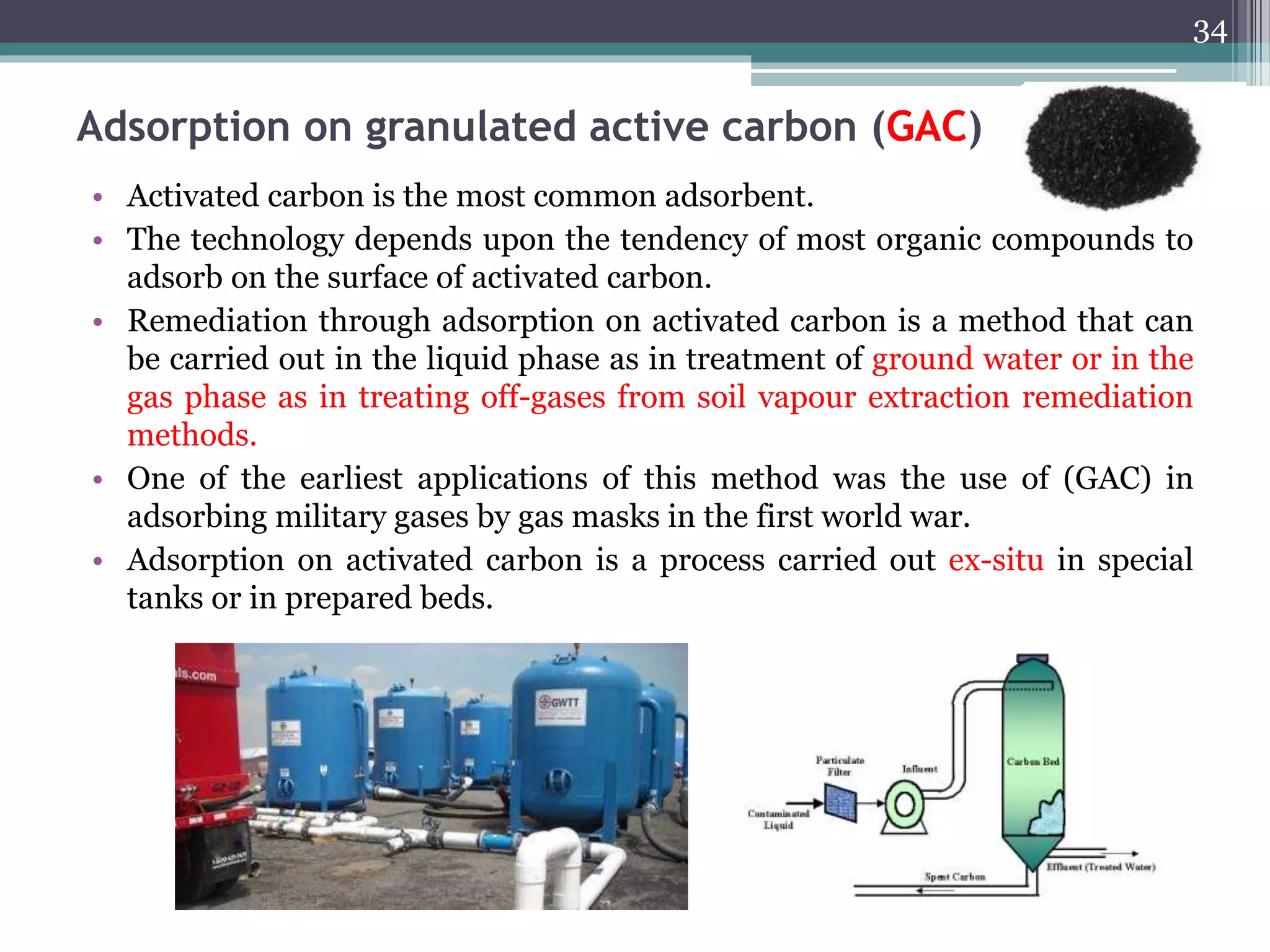

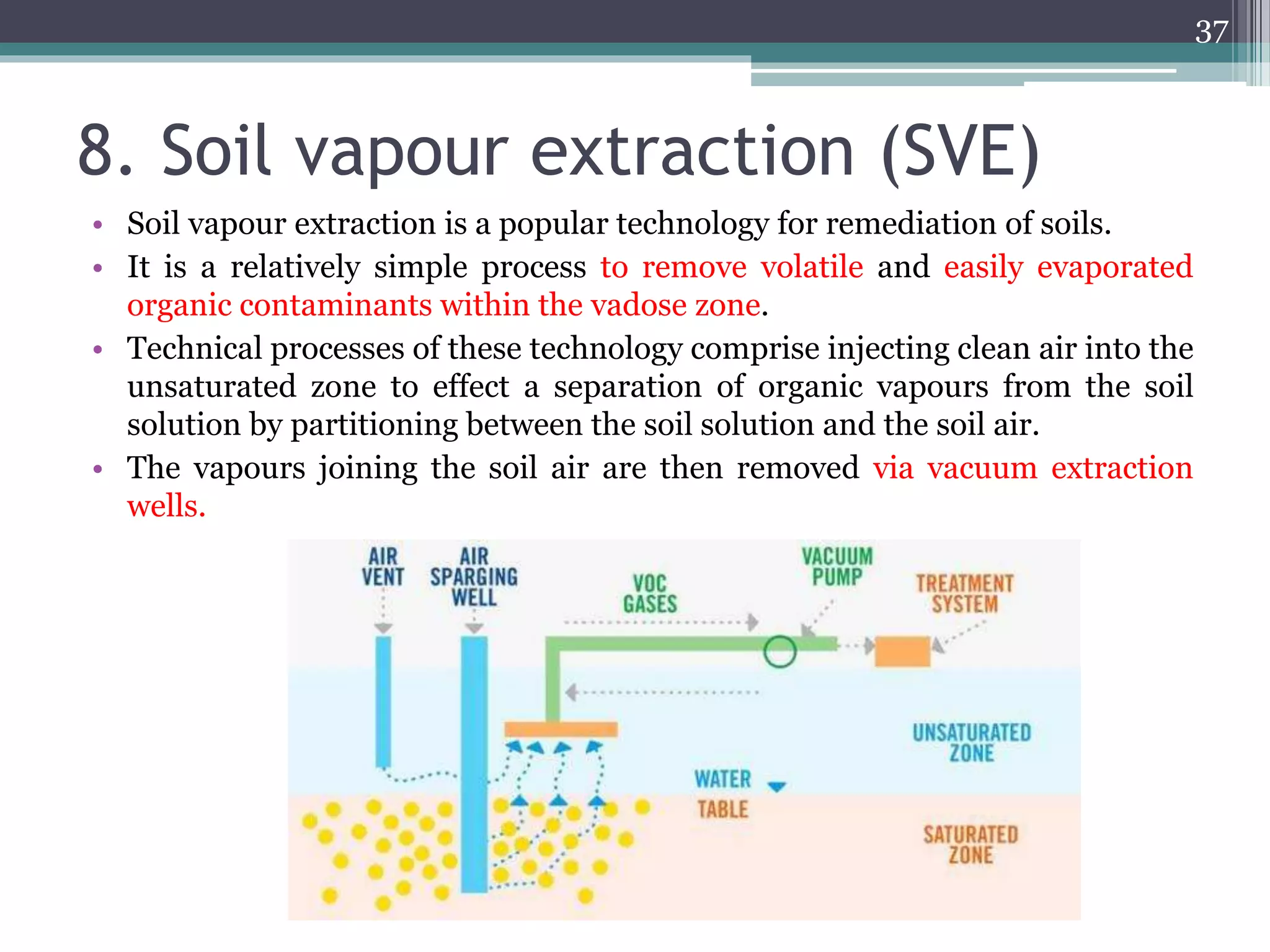

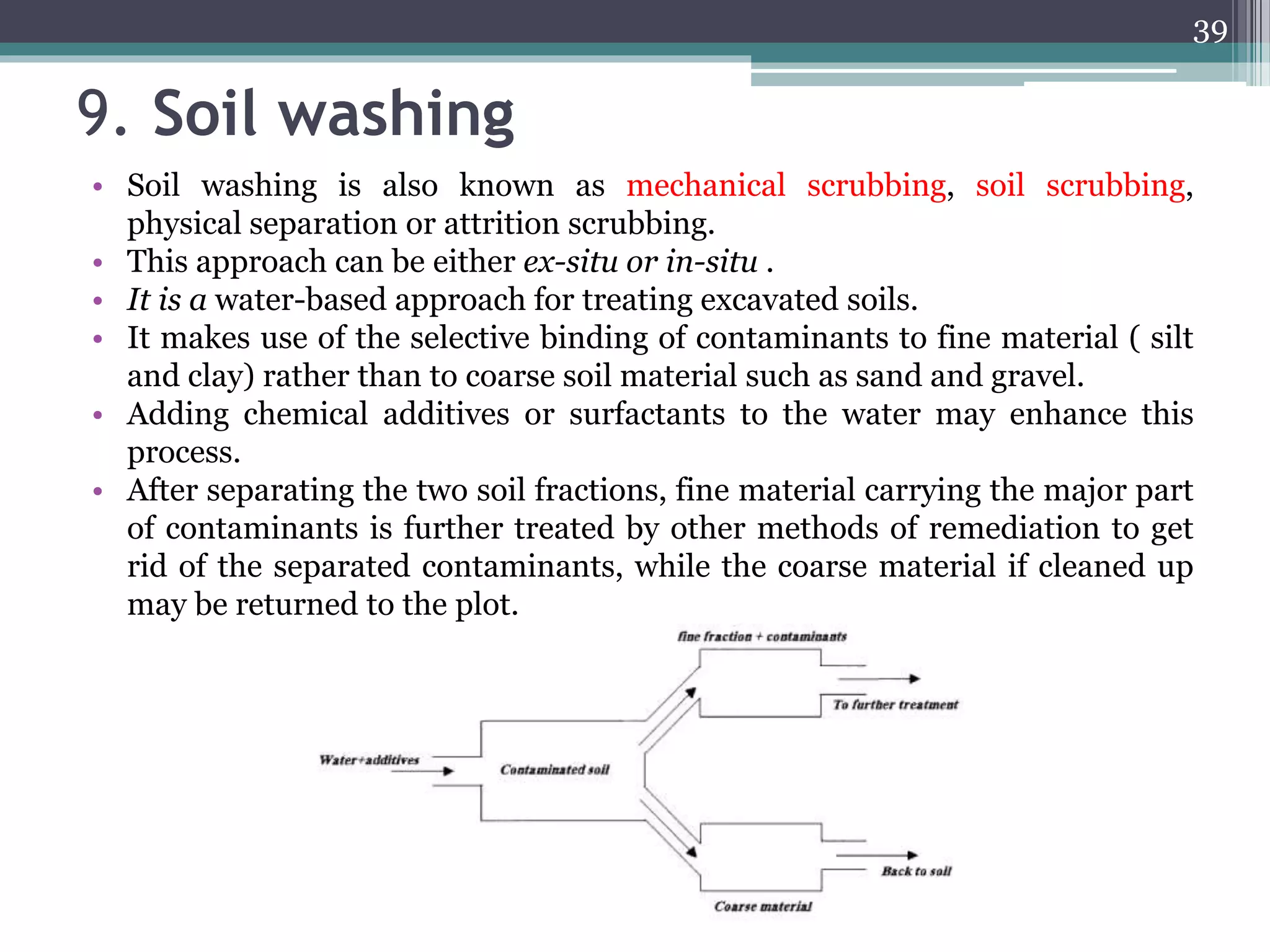

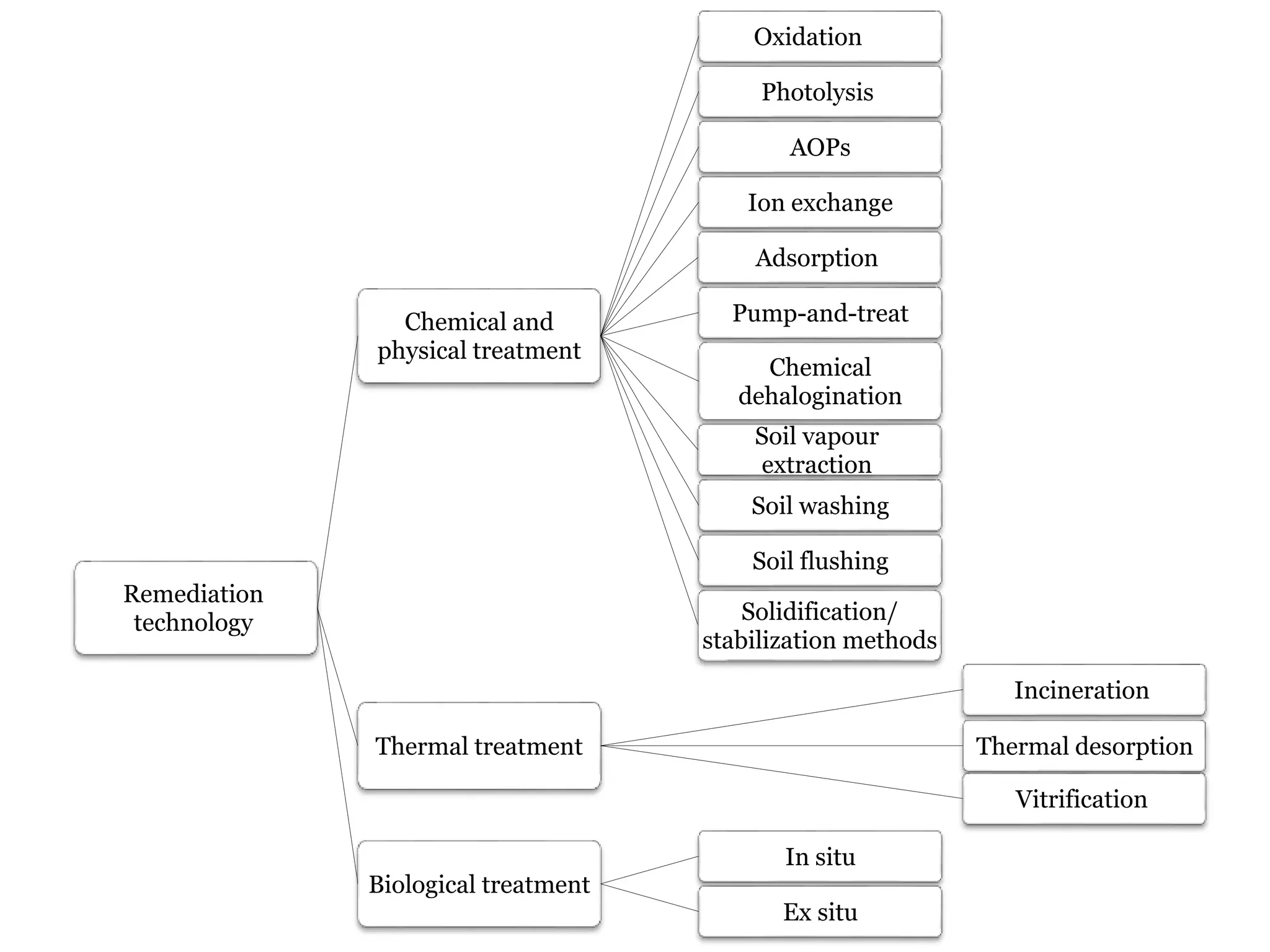

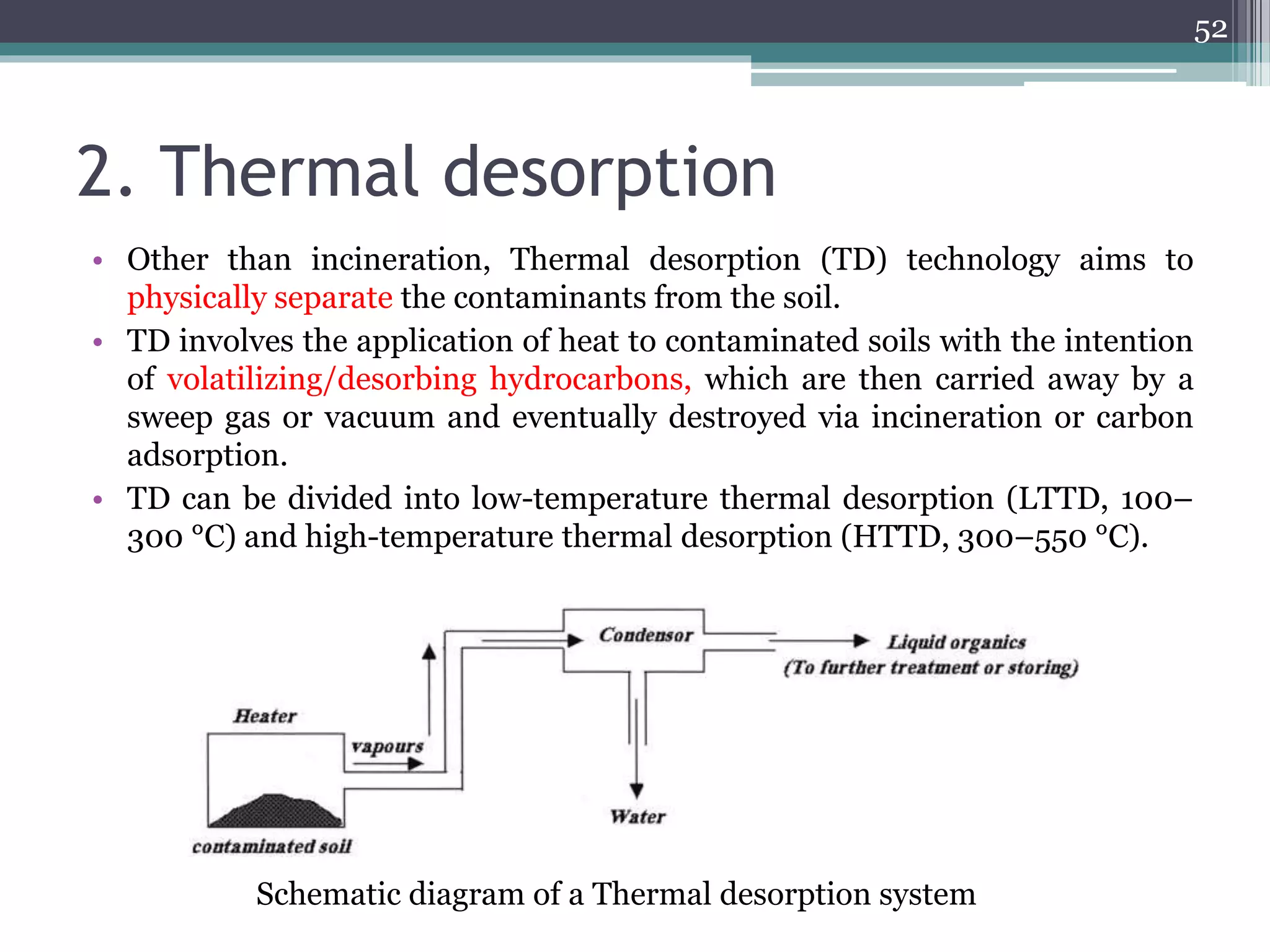

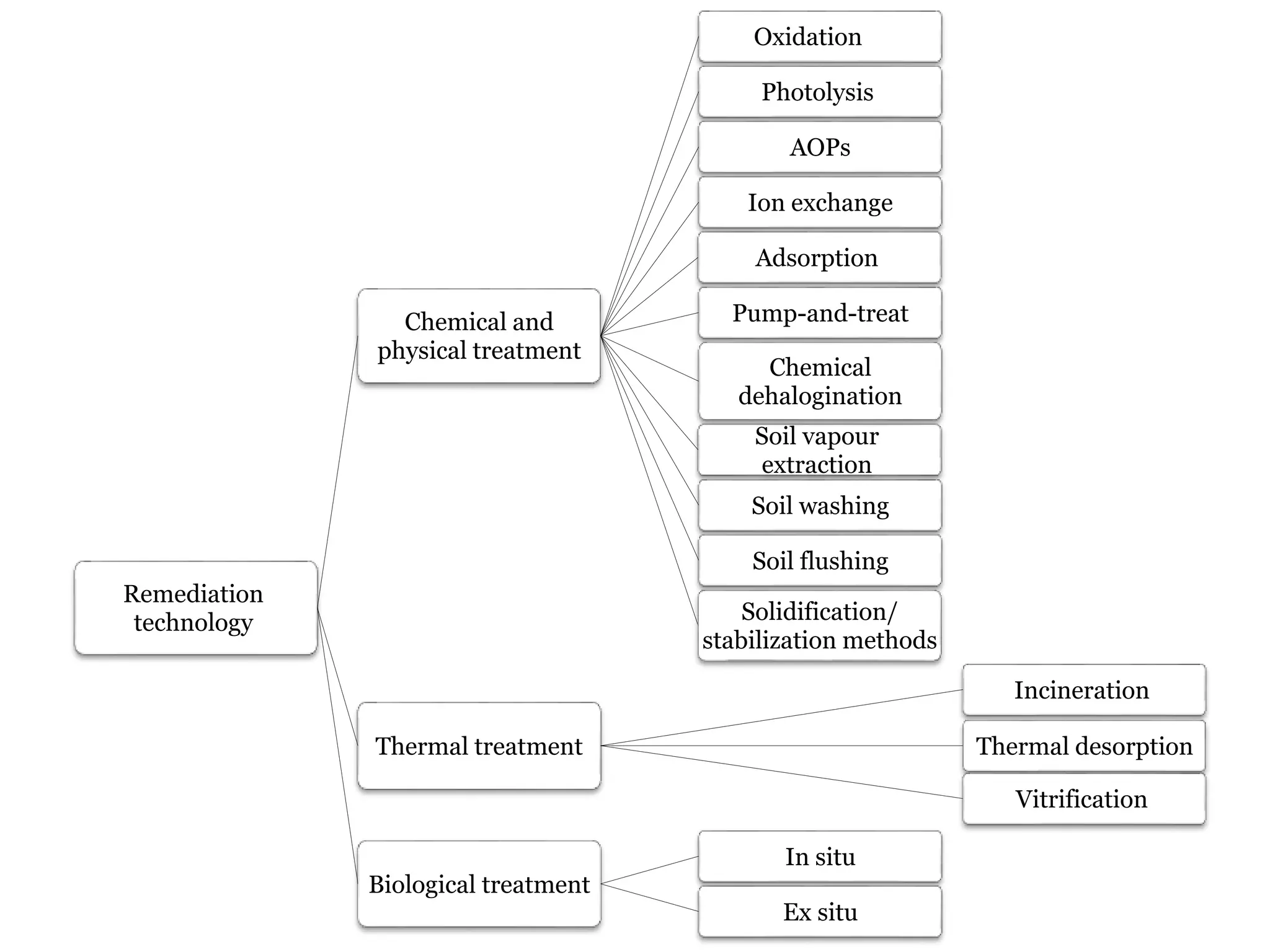

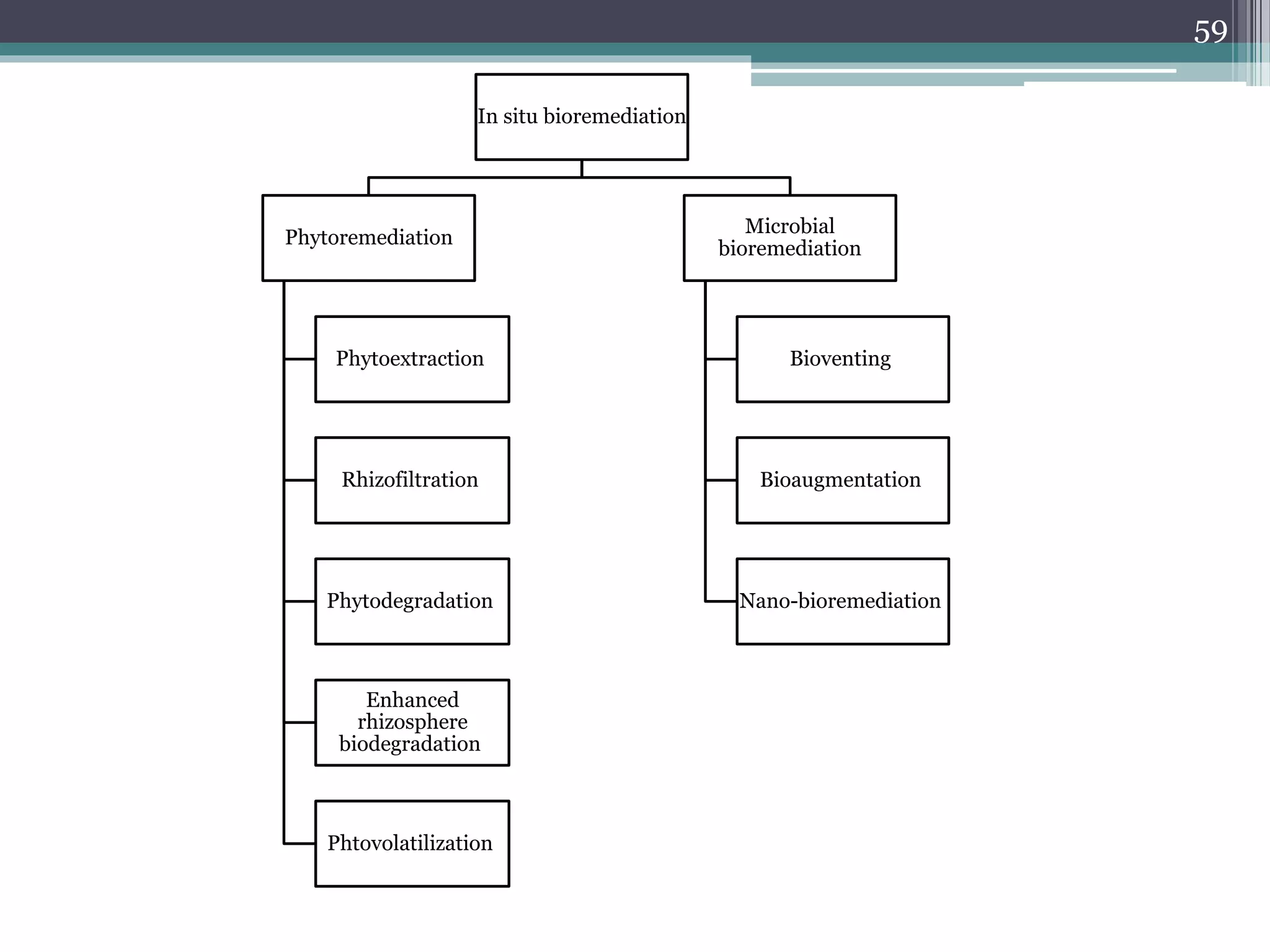

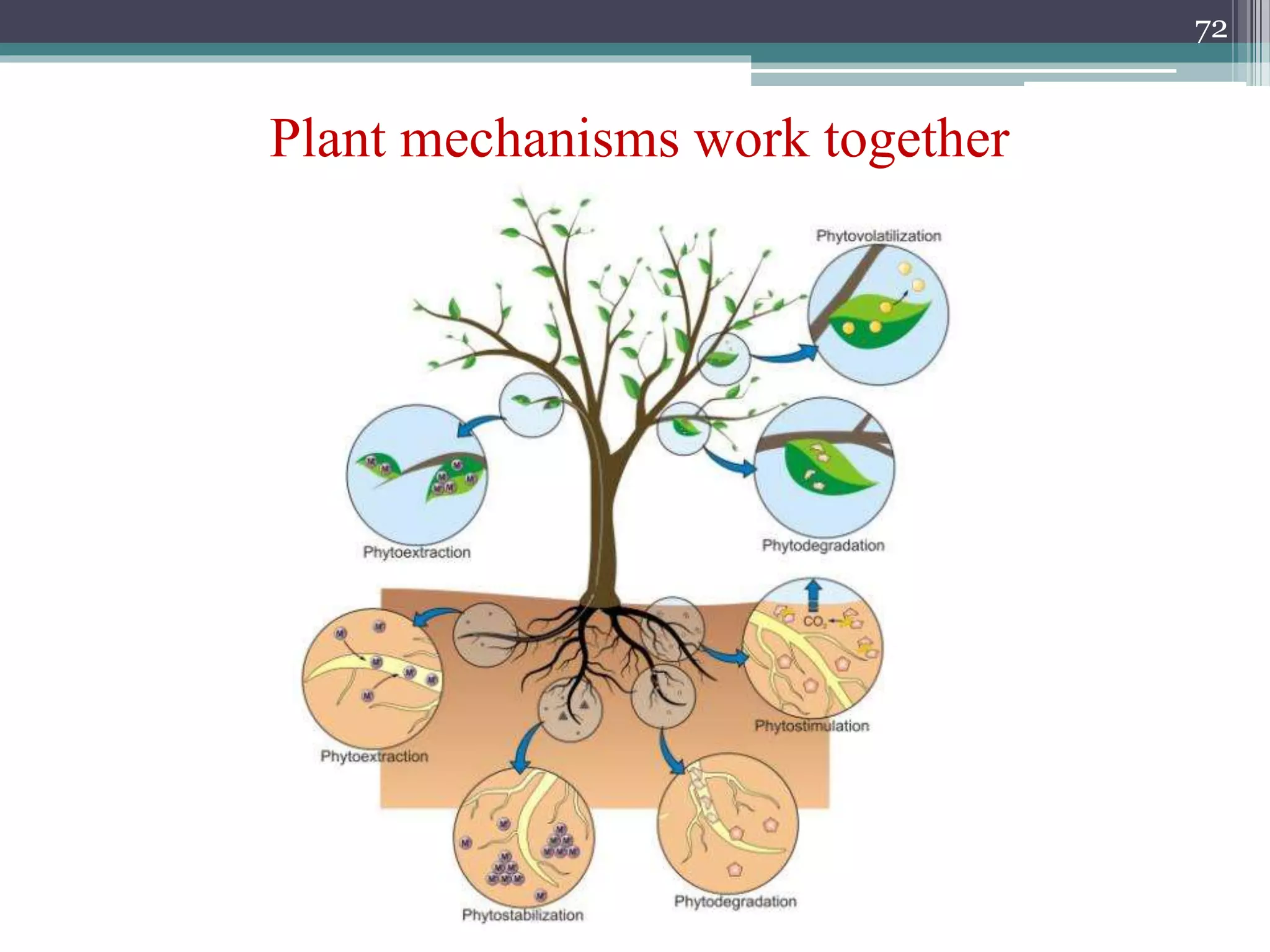

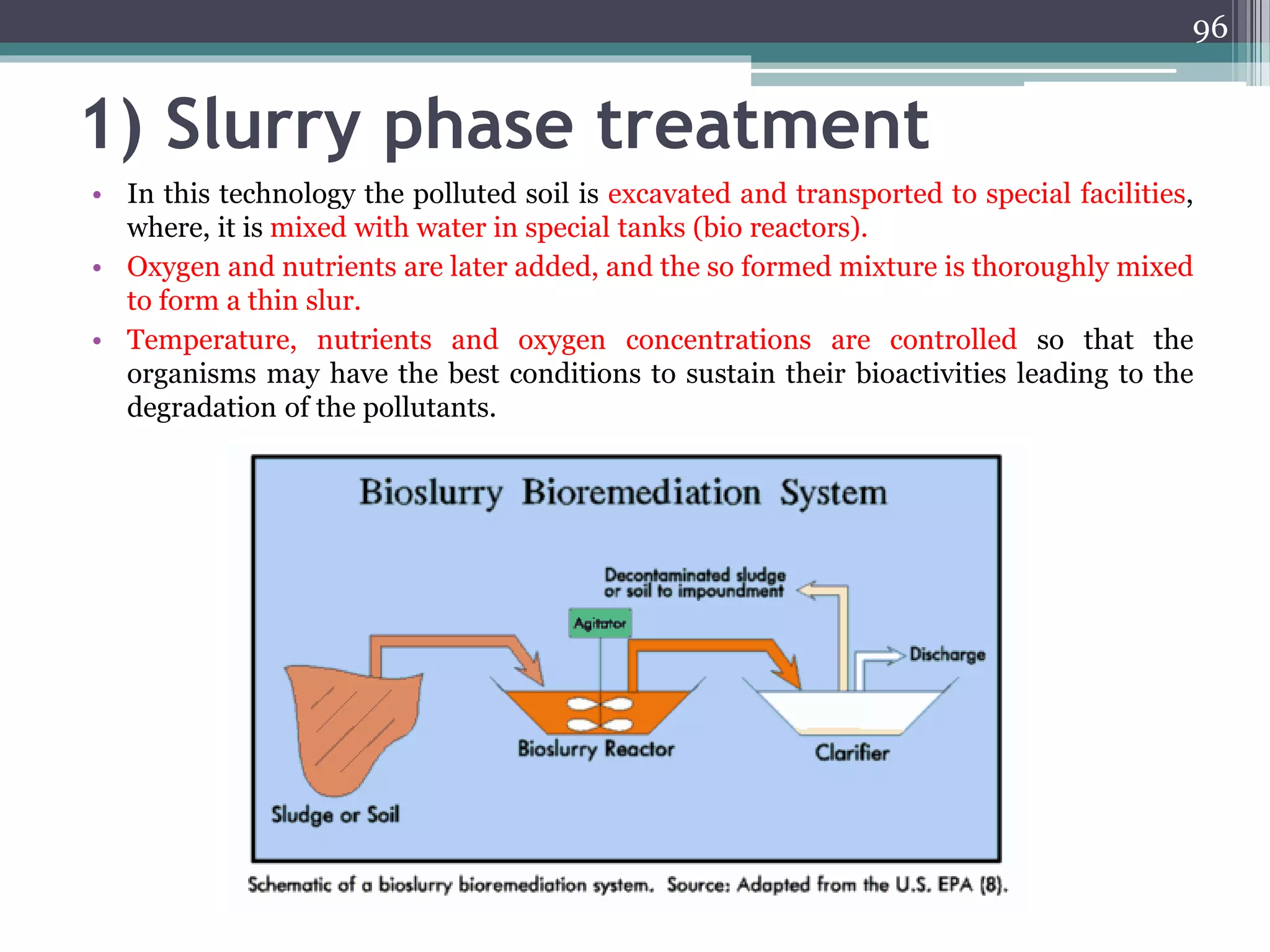

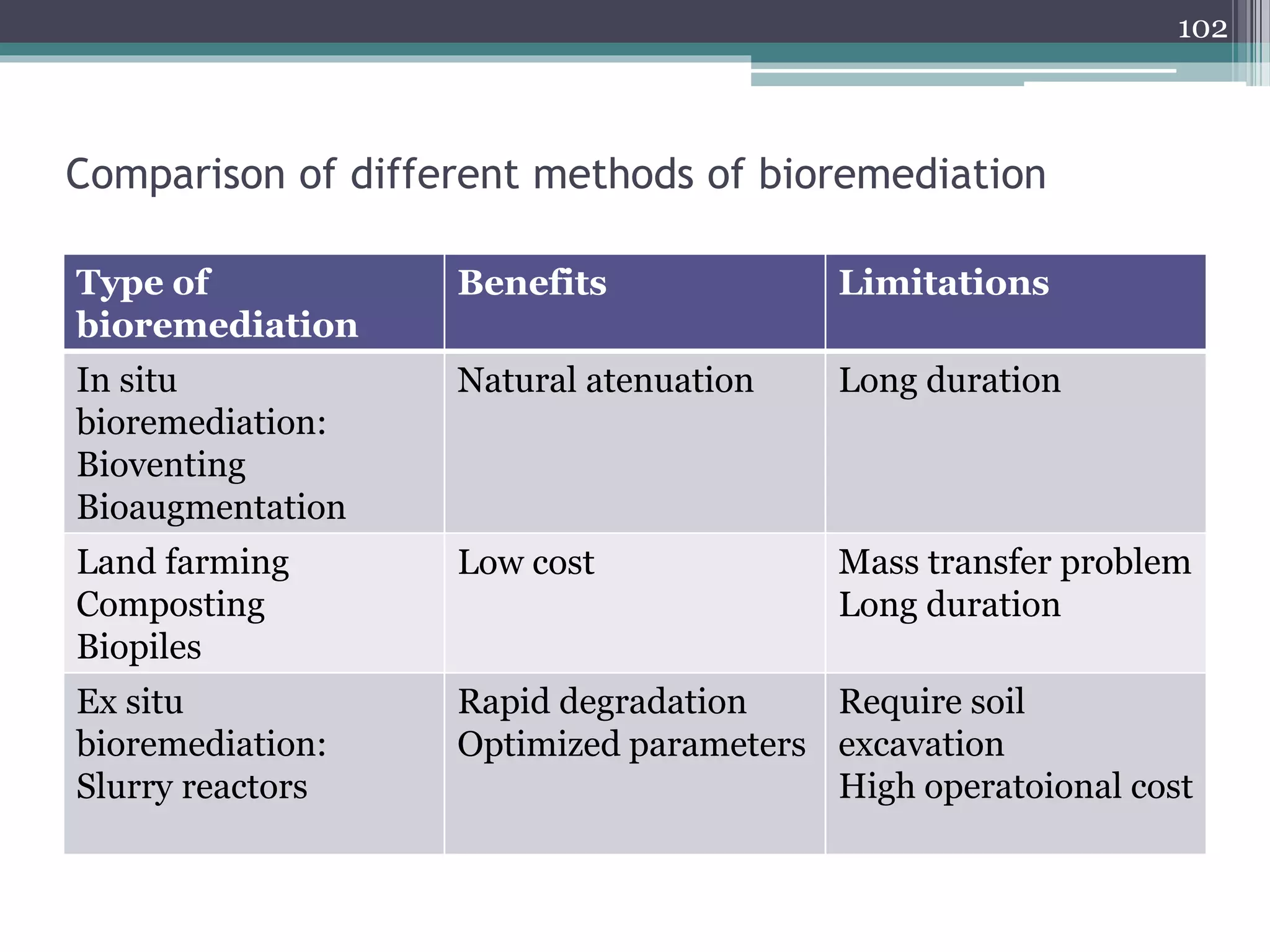

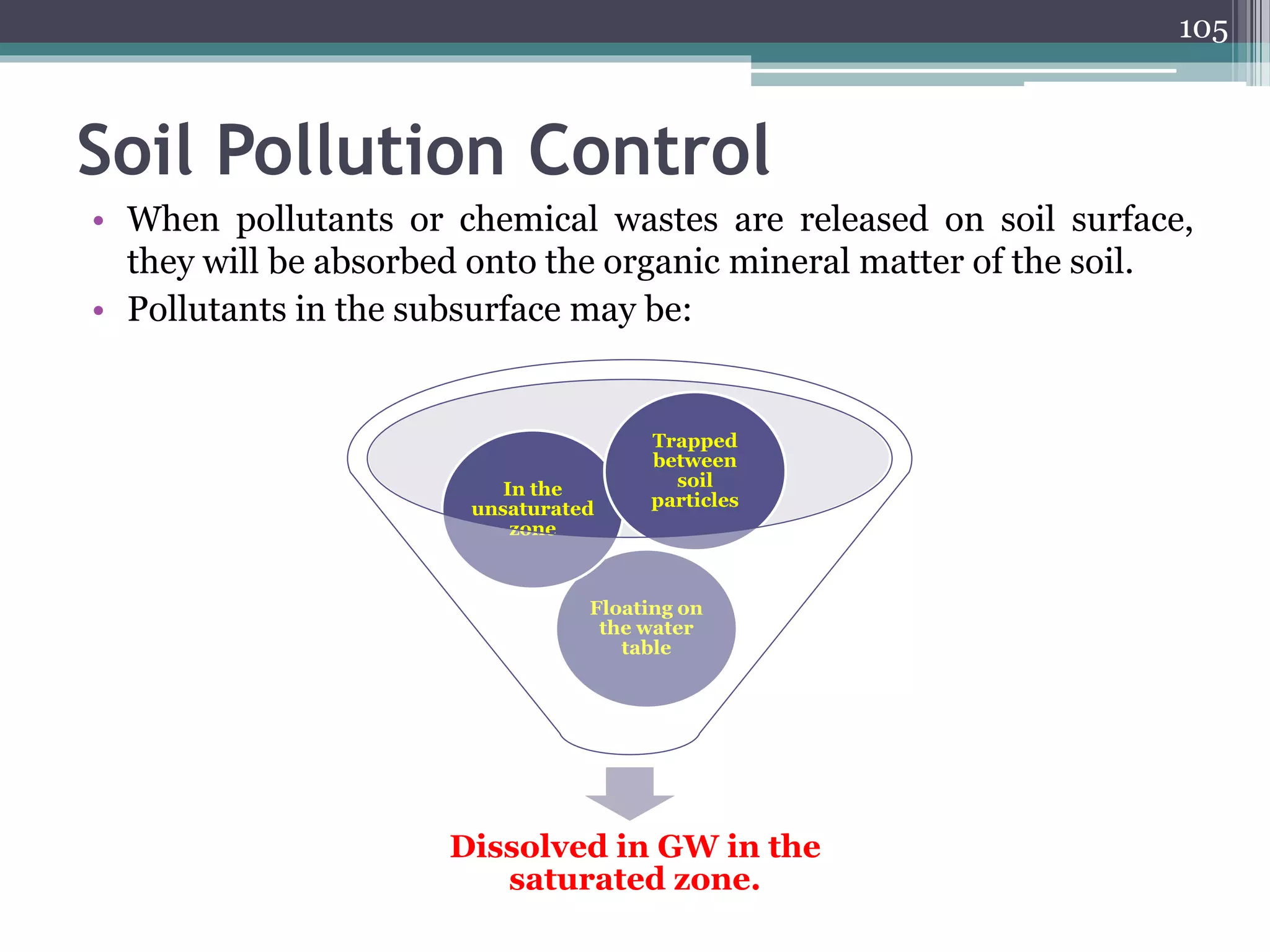

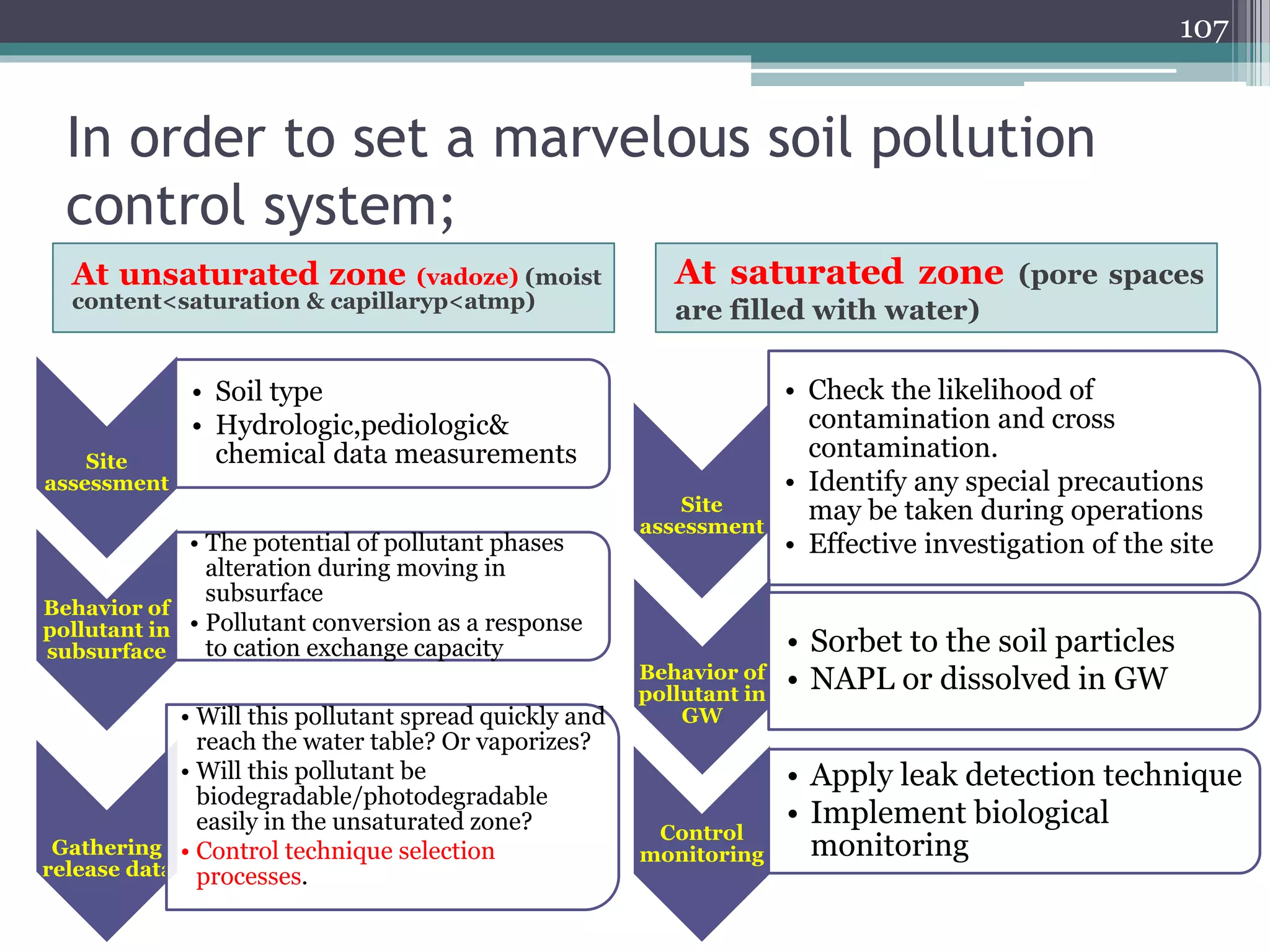

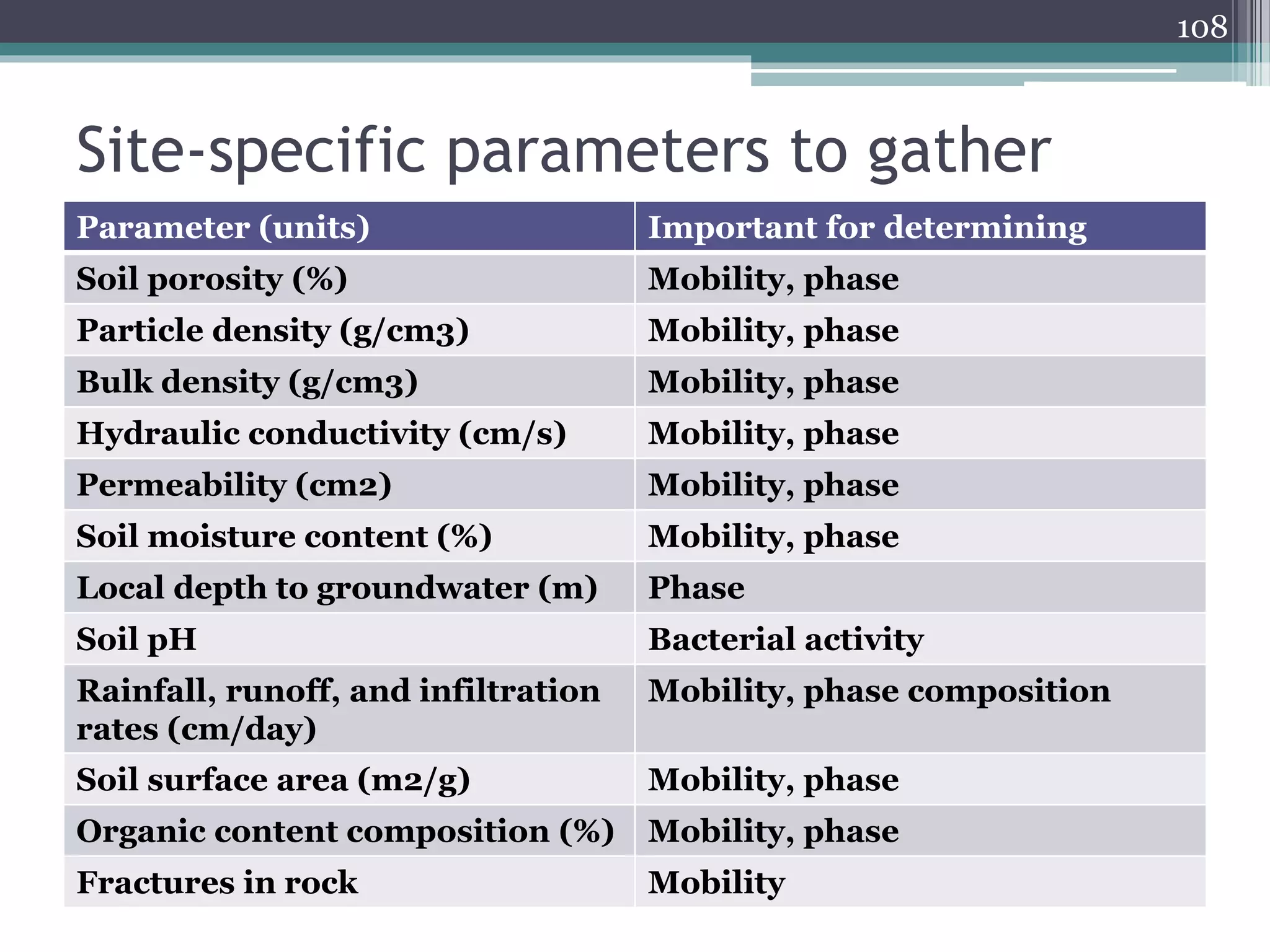

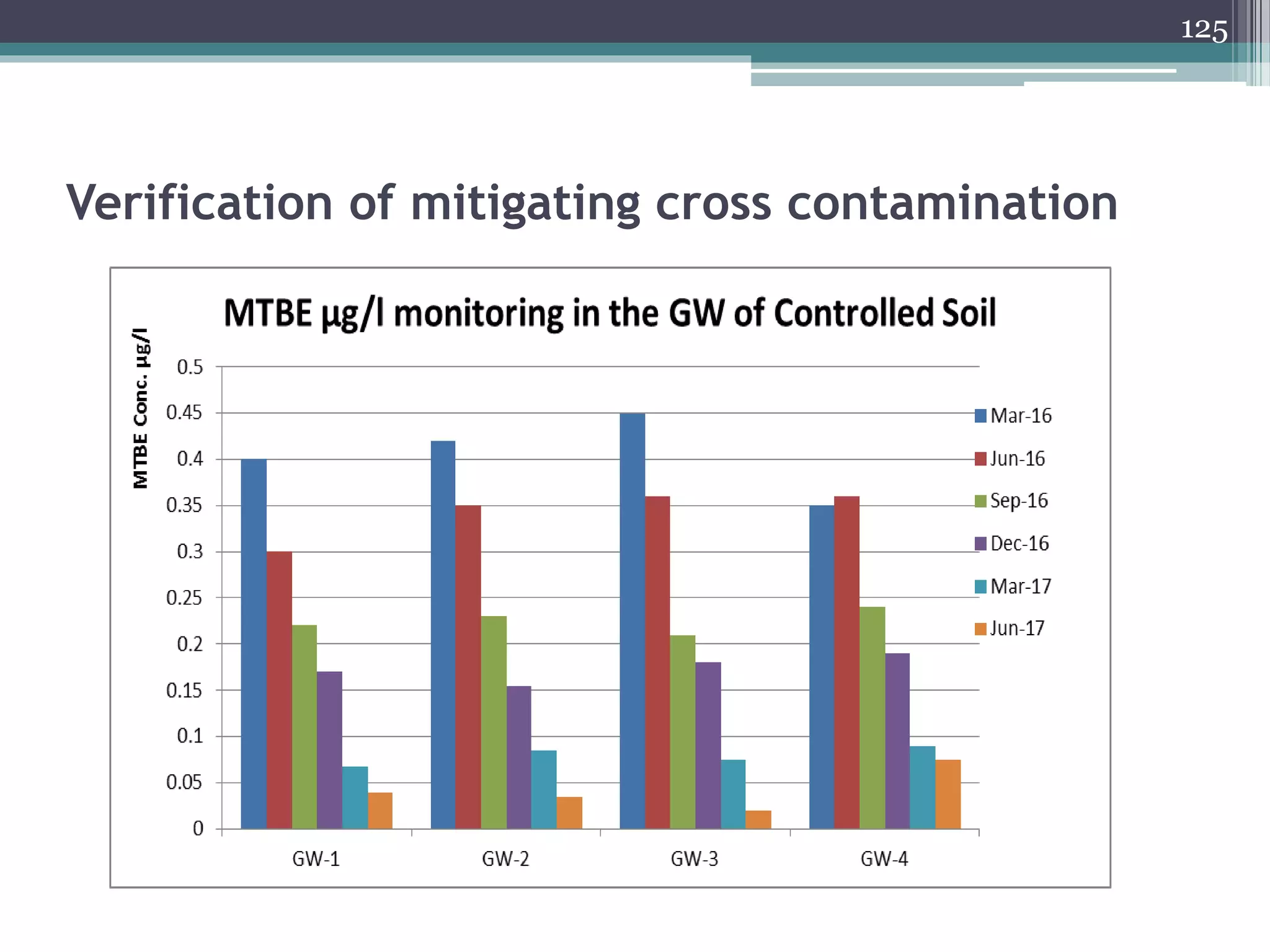

The document discusses the various impacts of soil pollution, including effects on ecosystems, human health, and agricultural productivity, primarily due to contaminants like heavy metals, pesticides, and non-aqueous phase liquids. It outlines the treatment and control measures for contaminated soils, which can range from physical and chemical methods to advanced oxidation processes and thermal treatment. Additionally, it addresses the socio-economic consequences of soil pollution and the complexity of remediating contaminated sites.