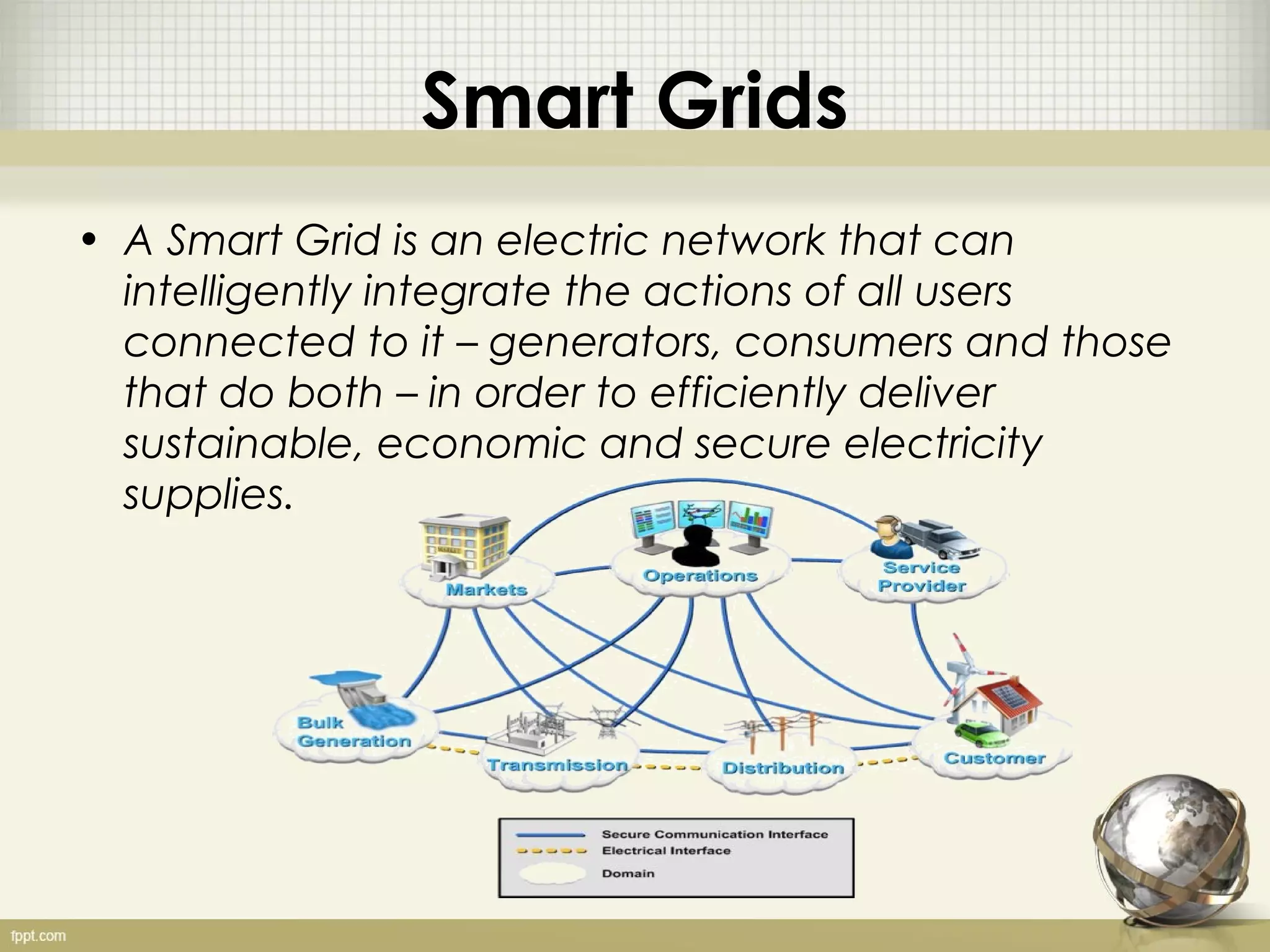

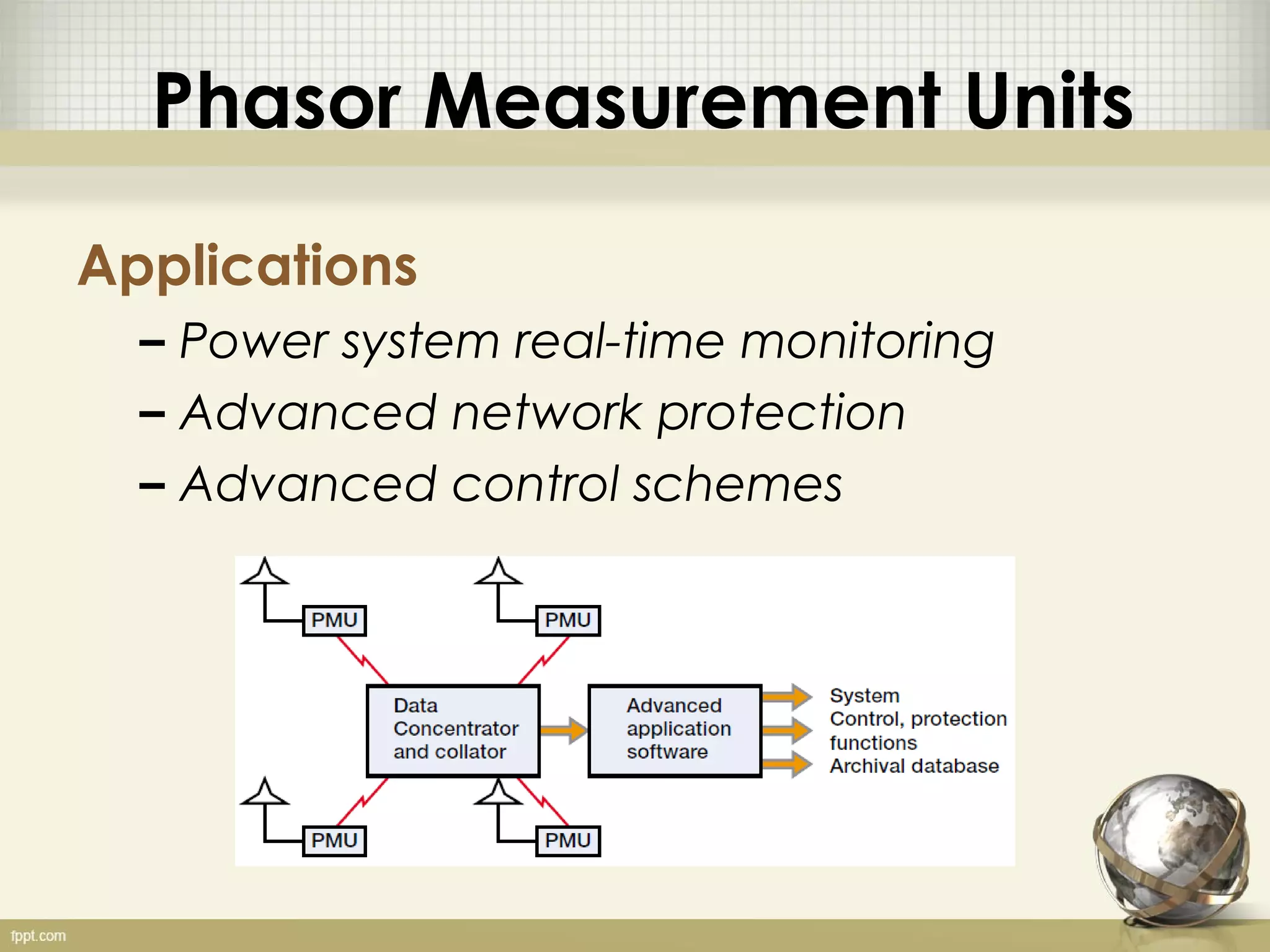

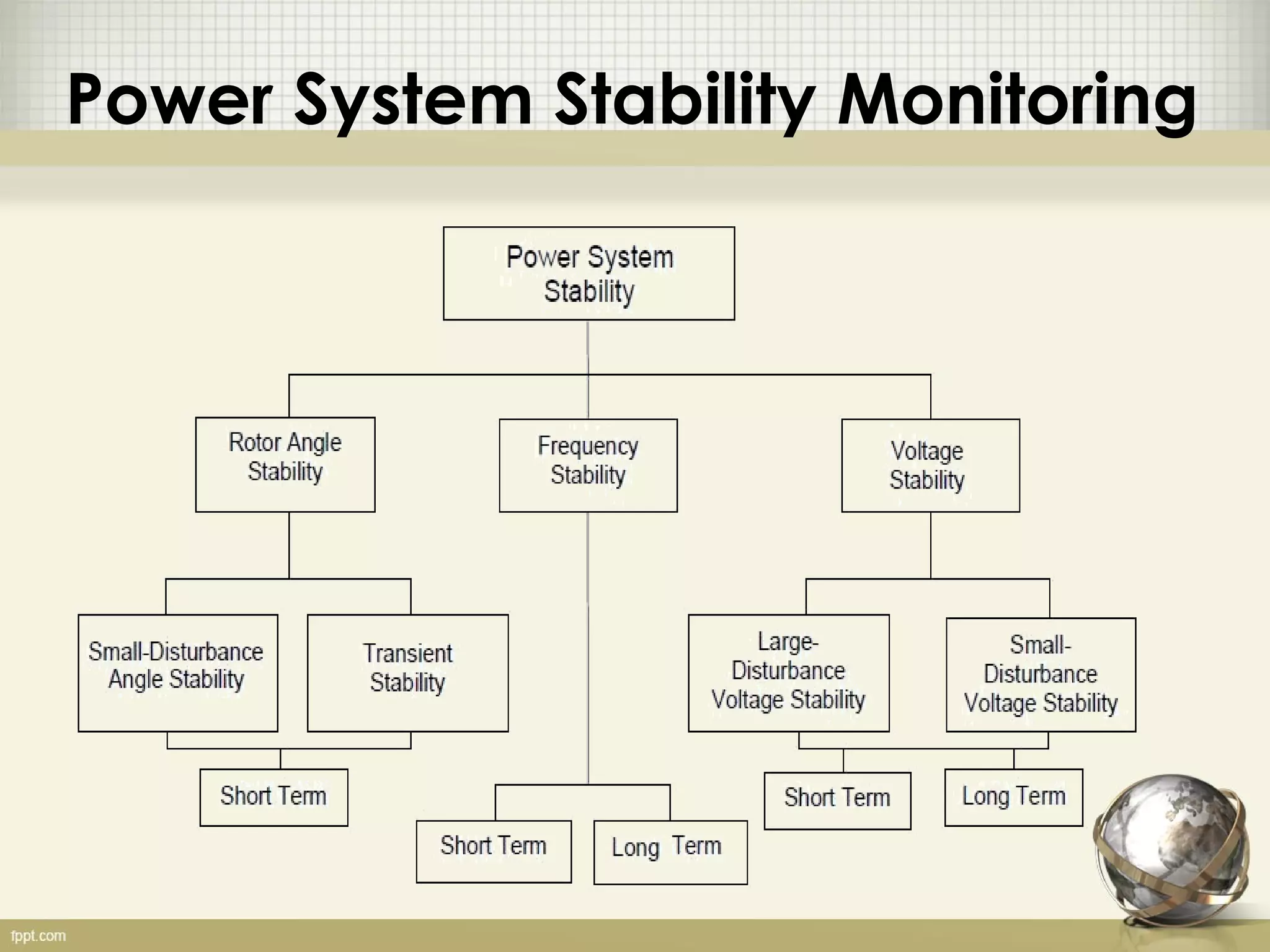

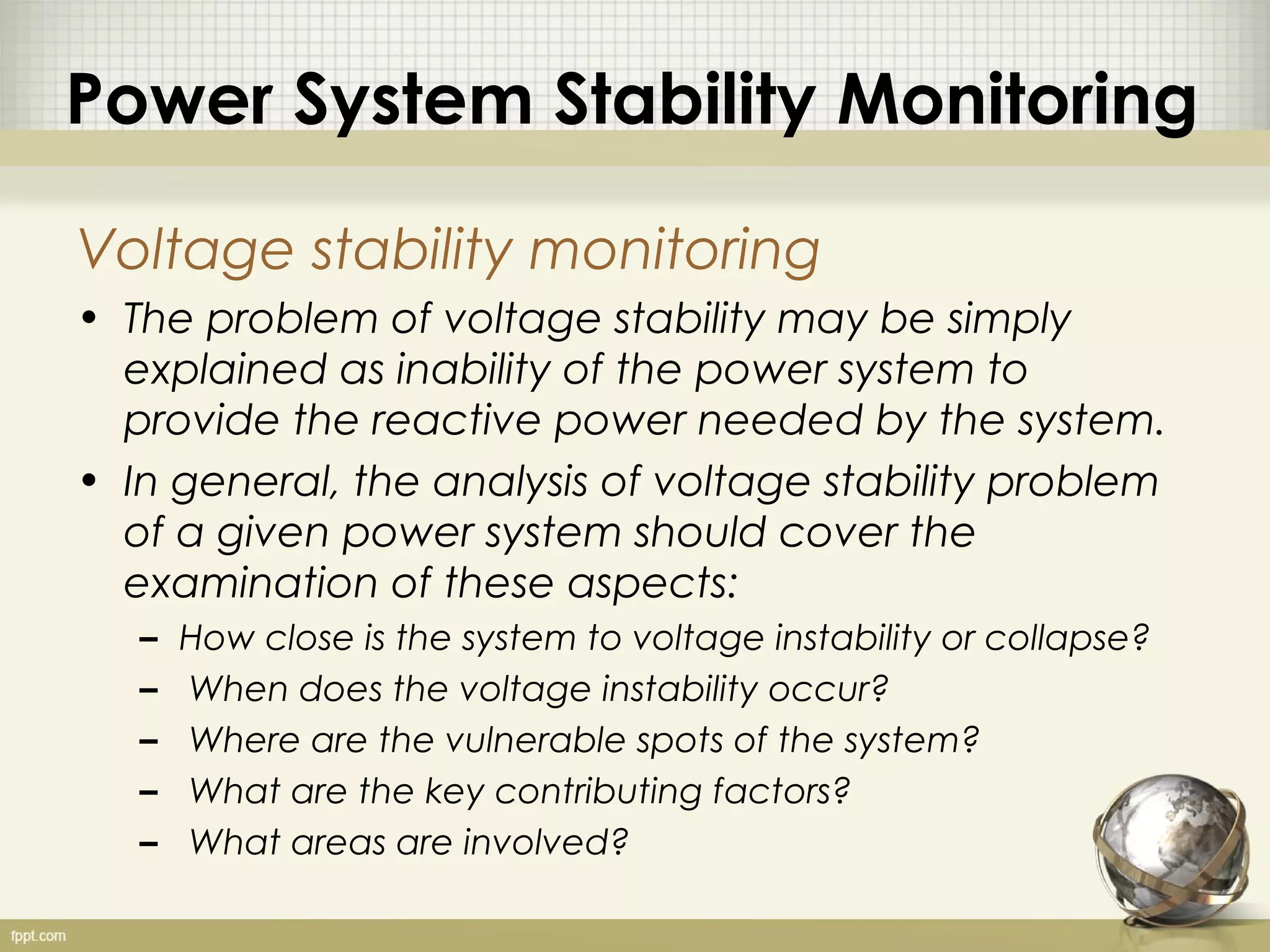

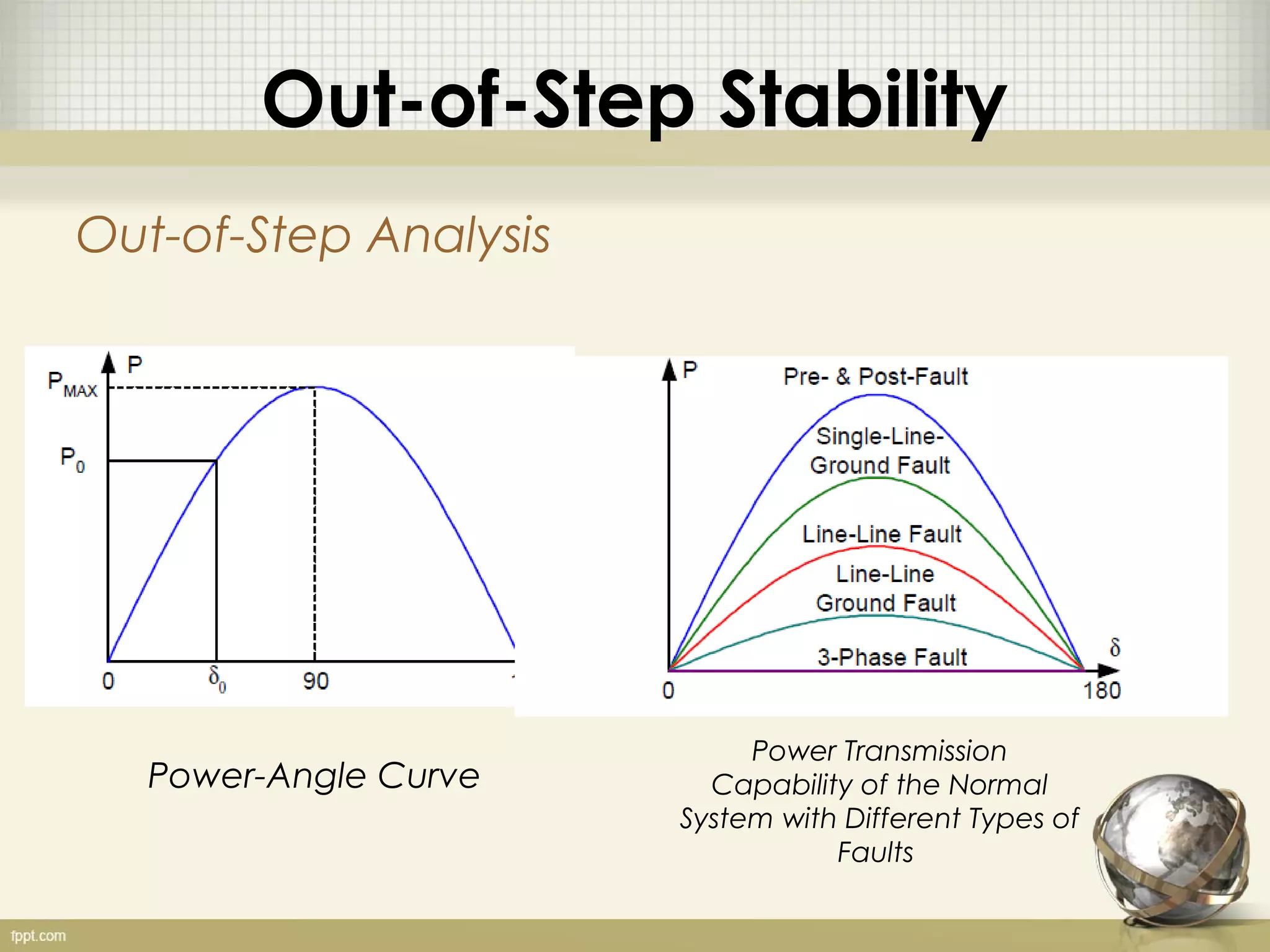

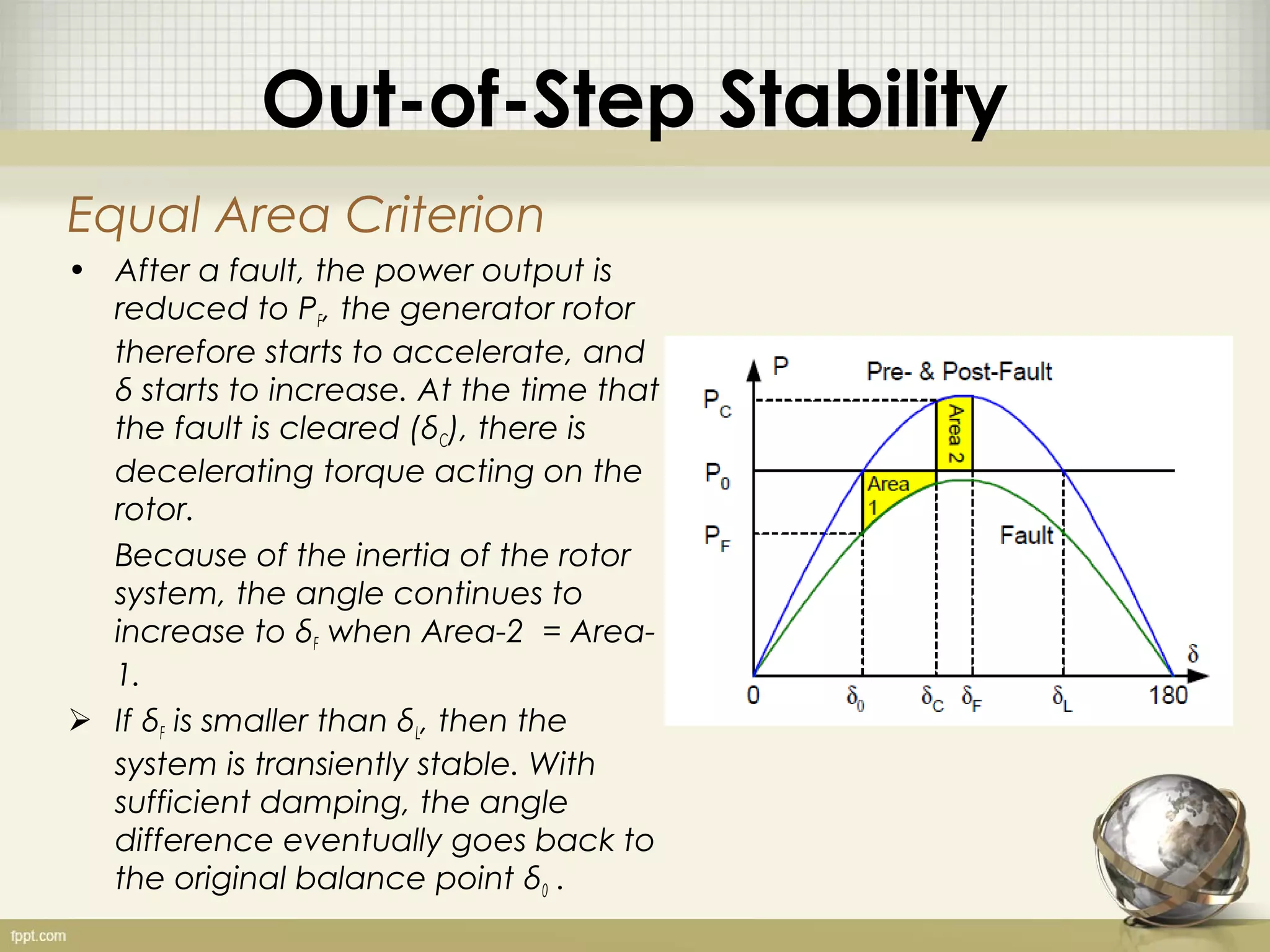

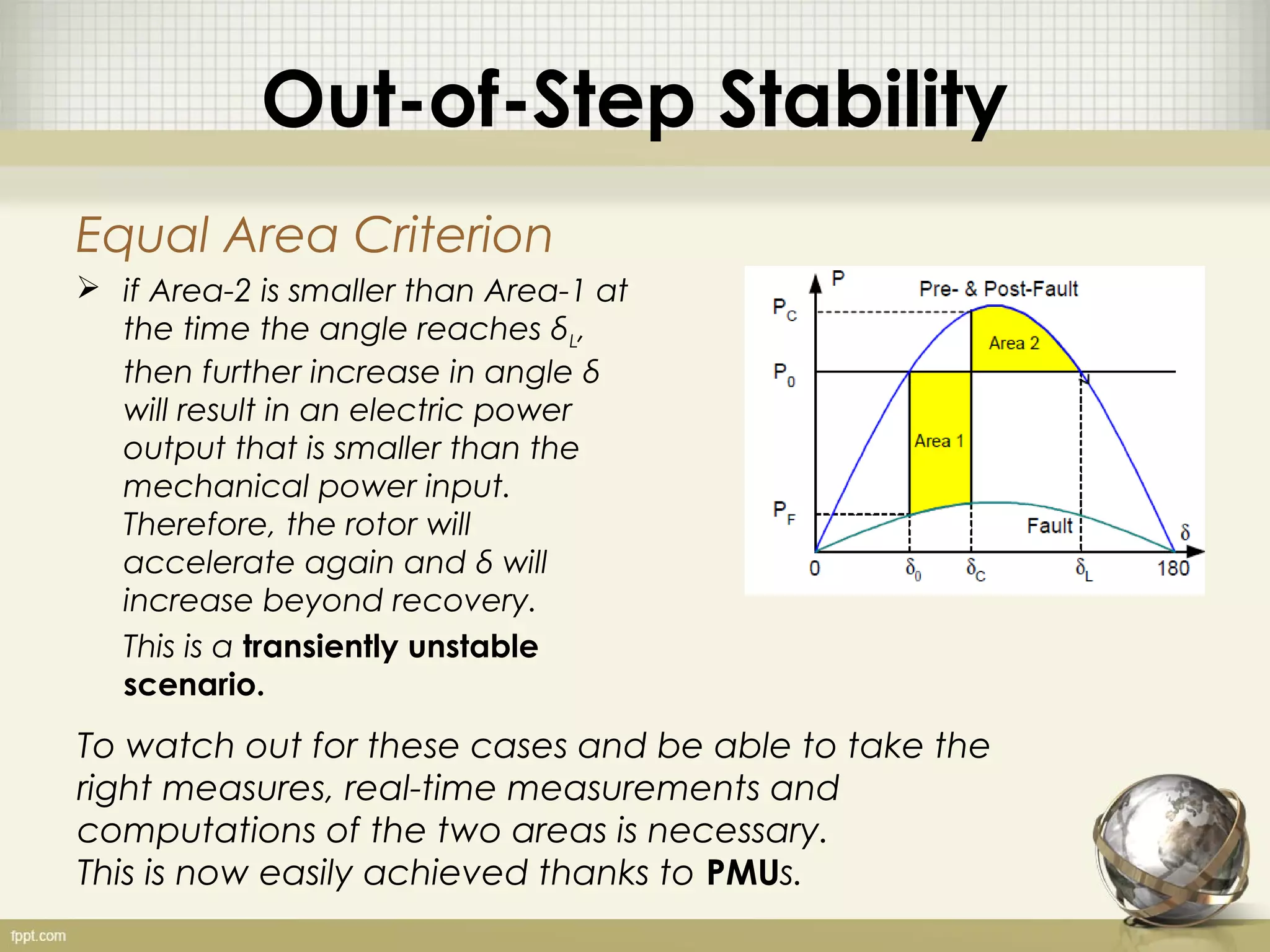

This document discusses monitoring in smart power grids using phasor measurement units (PMUs). It describes how PMUs provide real-time measurements that allow monitoring of key phenomena like islanding detection, line thermal monitoring, power system stability, and out-of-step stability. Monitoring is important for power assurance, visibility, efficiency and planning. PMU data supports applications like real-time monitoring, protection, and control and allows detection of oscillations and instability that could lead to blackouts. The conclusion emphasizes that modern monitoring delivers confidence in power system performance and ability to predict and prevent problems.