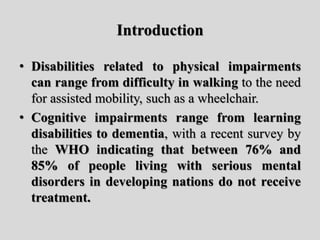

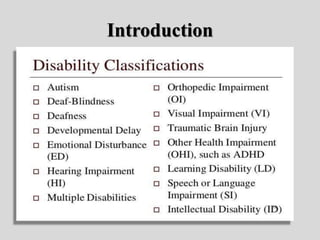

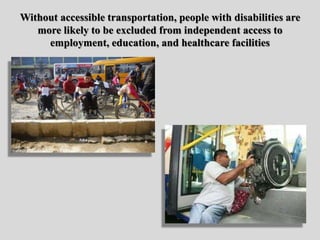

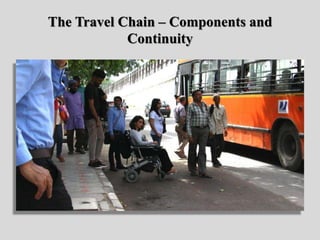

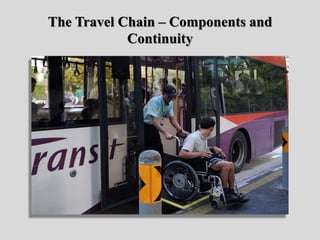

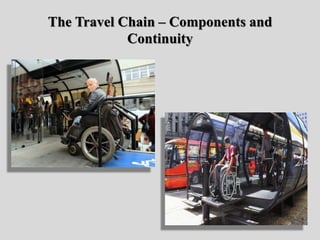

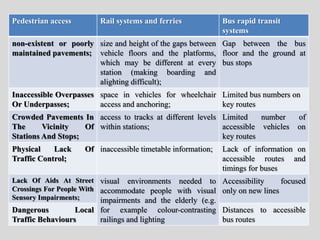

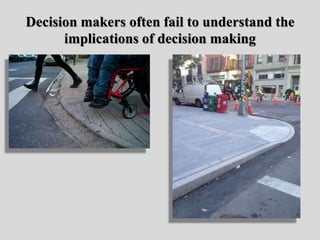

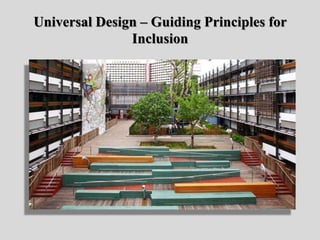

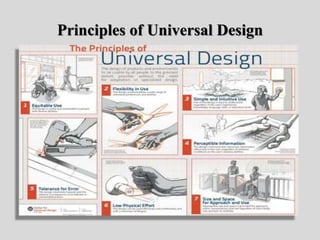

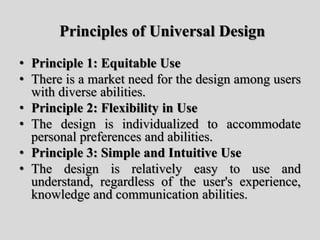

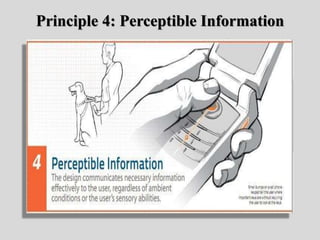

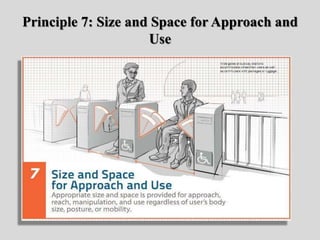

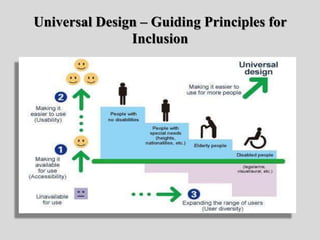

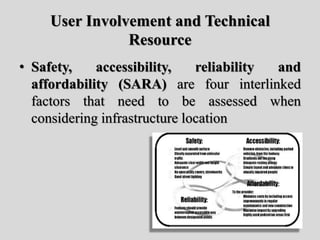

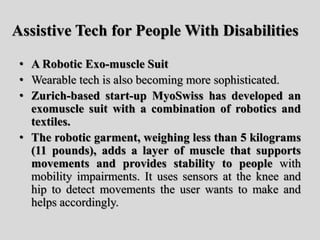

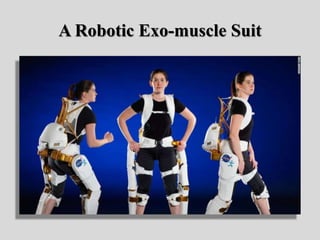

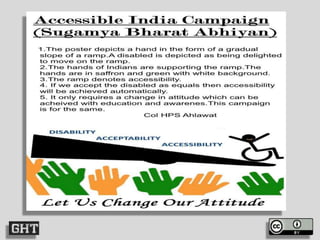

This document discusses considerations for ensuring infrastructure in smart cities is accessible to people with disabilities. It notes that around 15% of the world's population lives with a disability, and accessibility must be considered in planning smart cities. Universal design principles that make infrastructure usable by all are recommended, such as accessible transportation, buildings, information and communication technologies. Involving people with disabilities in the planning and design process is key to creating inclusive infrastructure.