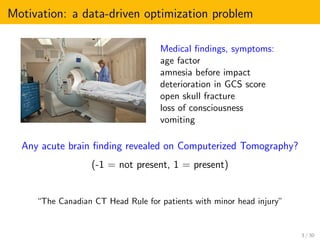

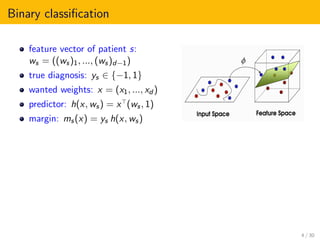

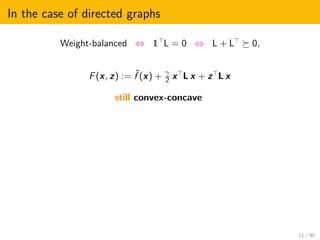

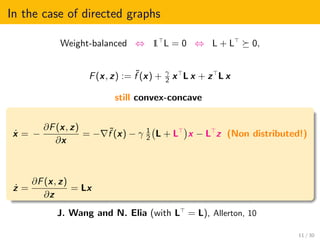

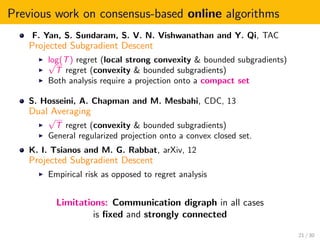

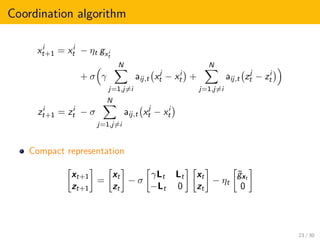

This document presents an overview of distributed online optimization over jointly connected digraphs. It discusses combining distributed convex optimization and online convex optimization frameworks. Specifically, it proposes a coordination algorithm for distributed online optimization over time-varying communication digraphs that are weight-balanced and jointly connected. The algorithm achieves sublinear regret bounds of O(sqrt(T)) under convexity and O(log(T)) under local strong convexity, using only local information and historical observations. This is an improvement over previous work that required fixed strongly connected digraphs or projection onto bounded sets.

![Our contributions (informally)

time-varying communication digraphs under B-joint connectivity &

weight-balanced

unconstrained optimization (no projection step onto a bounded set)

log T regret (local strong convexity & bounded subgradients)

√

T regret (convexity & β-centrality with β ∈ (0, 1] & bounded

subgradients)

22 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8366a48-50a3-422b-bf2a-dc755610443c-160415140434/85/slides_online_optimization_david_mateos-33-320.jpg)

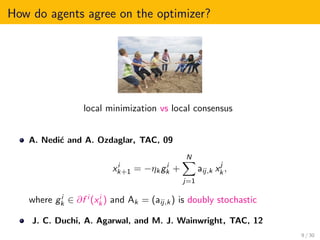

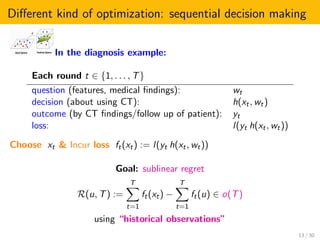

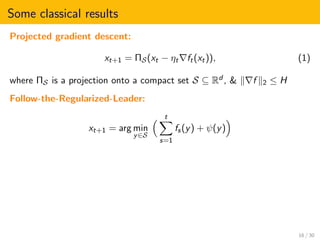

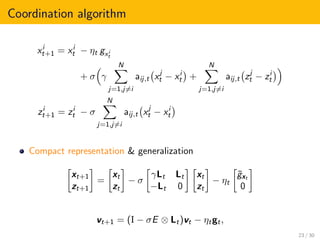

![Our contributions (informally)

time-varying communication digraphs under B-joint connectivity &

weight-balanced

unconstrained optimization (no projection step onto a bounded set)

log T regret (local strong convexity & bounded subgradients)

√

T regret (convexity & β-centrality with β ∈ (0, 1] & bounded

subgradients)

x∗

x

−ξx

f i

t is β-central in Z ⊆ Rd X∗,

where X∗ = x∗ : 0 ∈ ∂f i

t (x∗) ,

if ∀x ∈ Z, ∃x∗ ∈ X∗ such that

−ξx (x∗ − x)

ξx 2 x∗ − x 2

≥ β,

for each ξx ∈ ∂f i

t (x).

22 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8366a48-50a3-422b-bf2a-dc755610443c-160415140434/85/slides_online_optimization_david_mateos-34-320.jpg)

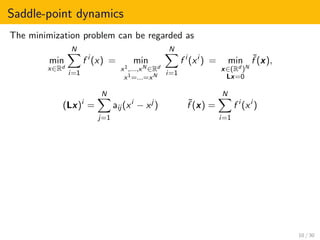

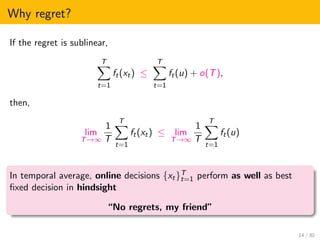

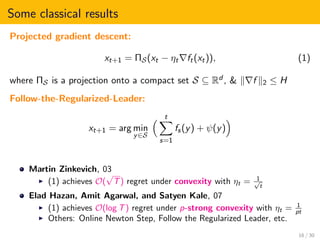

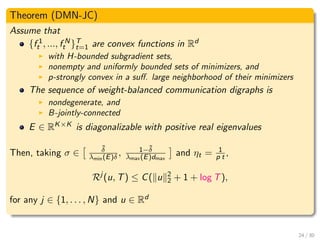

![Theorem (DMN-JC)

Assume that

{f 1

t , ..., f N

t }T

t=1 are convex functions in Rd

with H-bounded subgradient sets,

nonempty and uniformly bounded sets of minimizers, and

p-strongly convex in a suff. large neighborhood of their minimizers

The sequence of weight-balanced communication digraphs is

nondegenerate, and

B-jointly-connected

E ∈ RK×K is diagonalizable with positive real eigenvalues

Substituting strong convexity by β-centrality, for β ∈ (0, 1],

Rj

(u, T) ≤ C u 2

2

√

T,

for any j ∈ {1, . . . , N} and u ∈ Rd

24 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8366a48-50a3-422b-bf2a-dc755610443c-160415140434/85/slides_online_optimization_david_mateos-42-320.jpg)

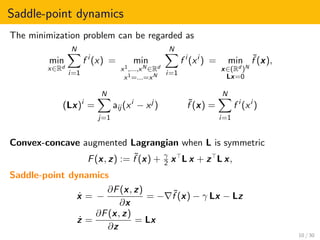

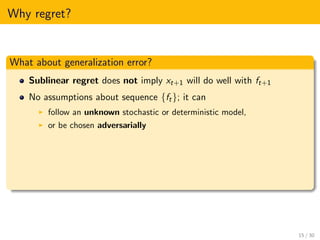

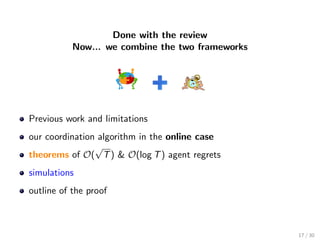

![Outline of the proof

Analysis of network regret

RN (u, T) :=

T

t=1

N

i=1

f i

t (xi

t ) −

T

t=1

N

i=1

f i

t (u)

ISS with respect to agreement

ˆLKvt 2 ≤ CI v1 2 1 −

˜δ

4N2

t−1

B

+ CU max

1≤s≤t−1

us 2,

Agent regret bound in terms of {ηt}t≥1 and initial conditions

Boundedness of online estimates under β-centrality (β ∈ (0, 1] )

Doubling trick to obtain O(

√

T) agent regret

Local strong convexity ⇒ β-centrality

ηt = 1

p t to obtain O(log T) agent regret

27 / 30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c8366a48-50a3-422b-bf2a-dc755610443c-160415140434/85/slides_online_optimization_david_mateos-45-320.jpg)