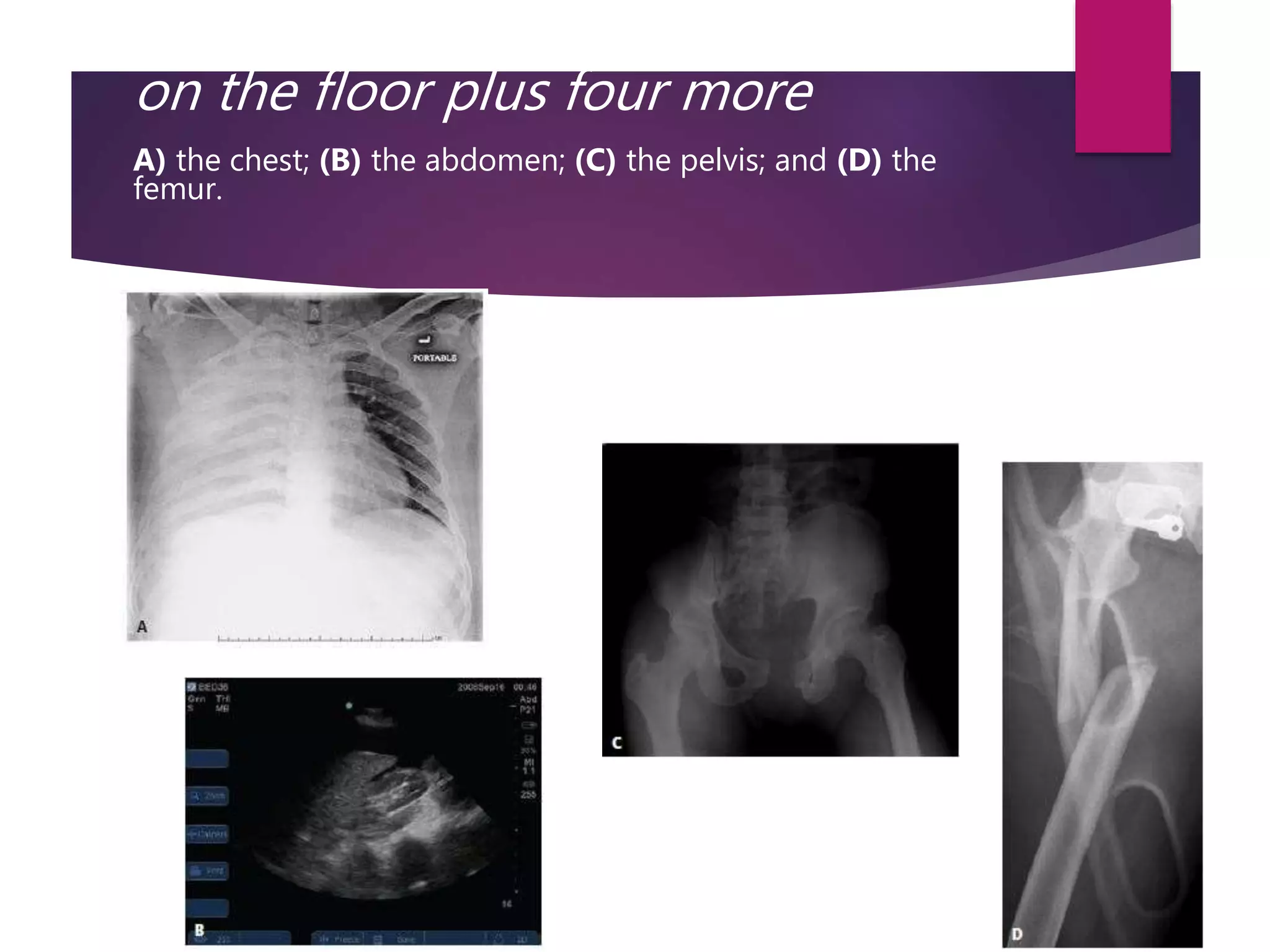

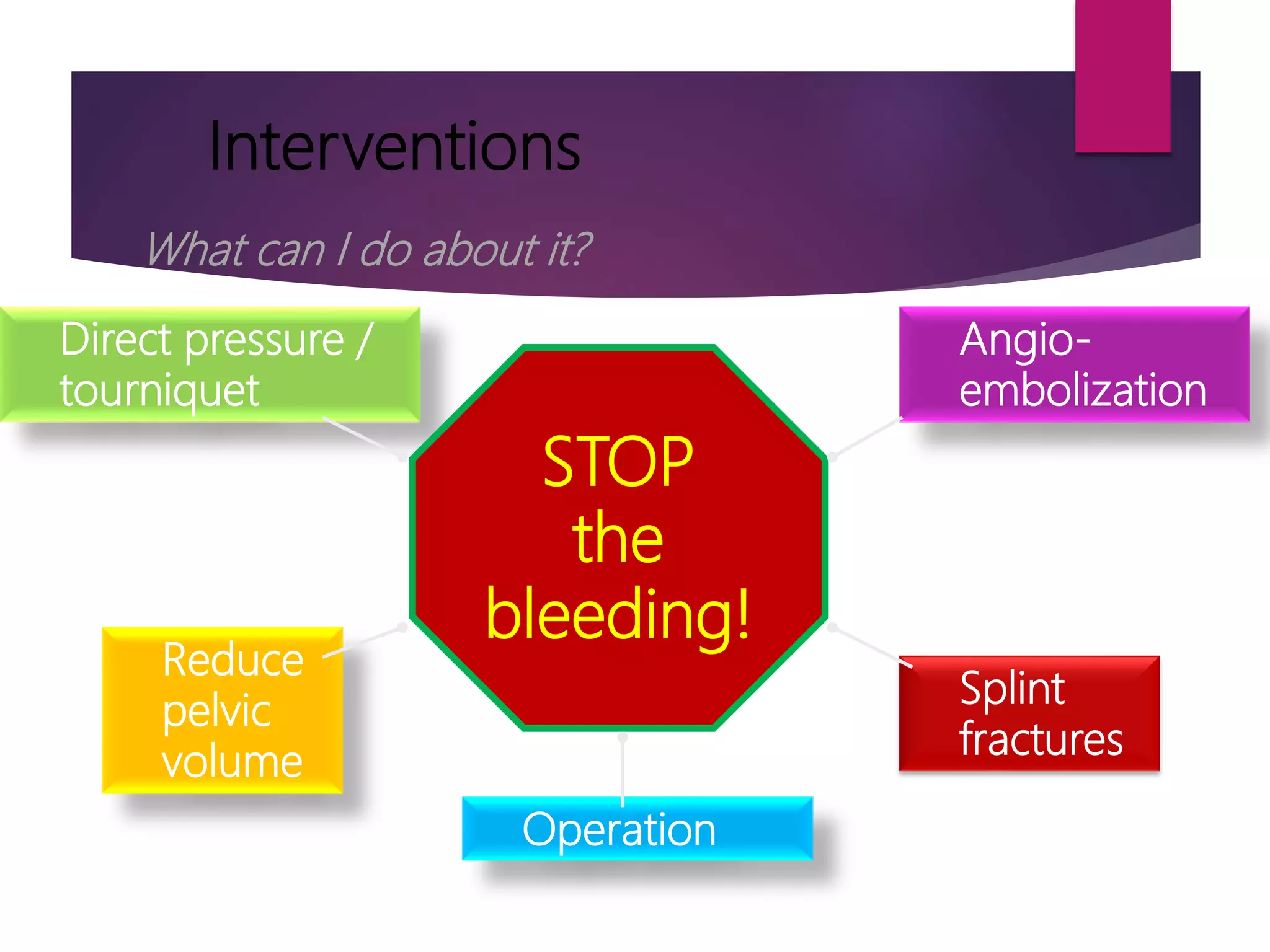

Shock is a state of low tissue perfusion caused by inadequate oxygen delivery. The initial assessment of a shocked patient involves determining if they are in shock and the cause. Hemorrhage is the most common cause of shock in trauma patients. The management of hemorrhagic shock involves stopping the bleeding through direct pressure, tourniquets, or surgery and replacing lost volume with intravenous fluids and blood products. Fluid resuscitation alone is not sufficient and the bleeding must be controlled through surgical or angiographic methods. Early recognition and treatment can prevent many trauma deaths from shock.