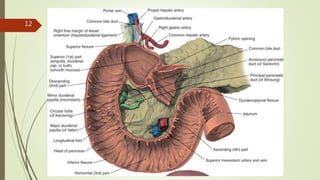

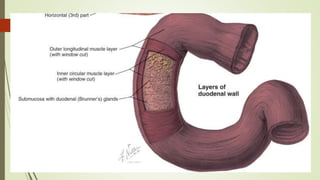

The stomach and duodenum develop from the foregut and midgut during embryology. The stomach is fixed at both ends while the midportion is mobile. It receives blood supply from the left and right gastric arteries and drains into the portal vein. Nerve supply is from the vagus nerve. The duodenum is lined by a mucus-secreting columnar epithelium and contains Brunner's glands which secrete bicarbonate and epidermal growth factor. The stomach breaks down food into chyme using acid and pepsin while the duodenum maintains an alkaline environment using bicarbonate from the pancreas and duodenum. Hormones like gastr