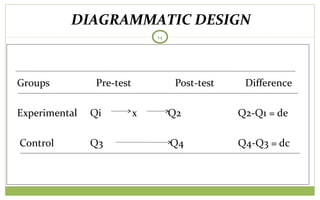

The document discusses different research design frameworks, including classical experimental design, cross-sectional design, and quantitative-qualitative design. For classical experimental design, it describes the key elements of having an experimental and control group, manipulating an independent variable, pre-testing and post-testing, and comparing results. Cross-sectional design is more common in social sciences and uses statistical analysis rather than manipulation. Quantitative design seeks to objectively explain social facts while qualitative design understands social phenomena from participant perspectives. The appropriate design depends on the research question, level of control, and type of data.