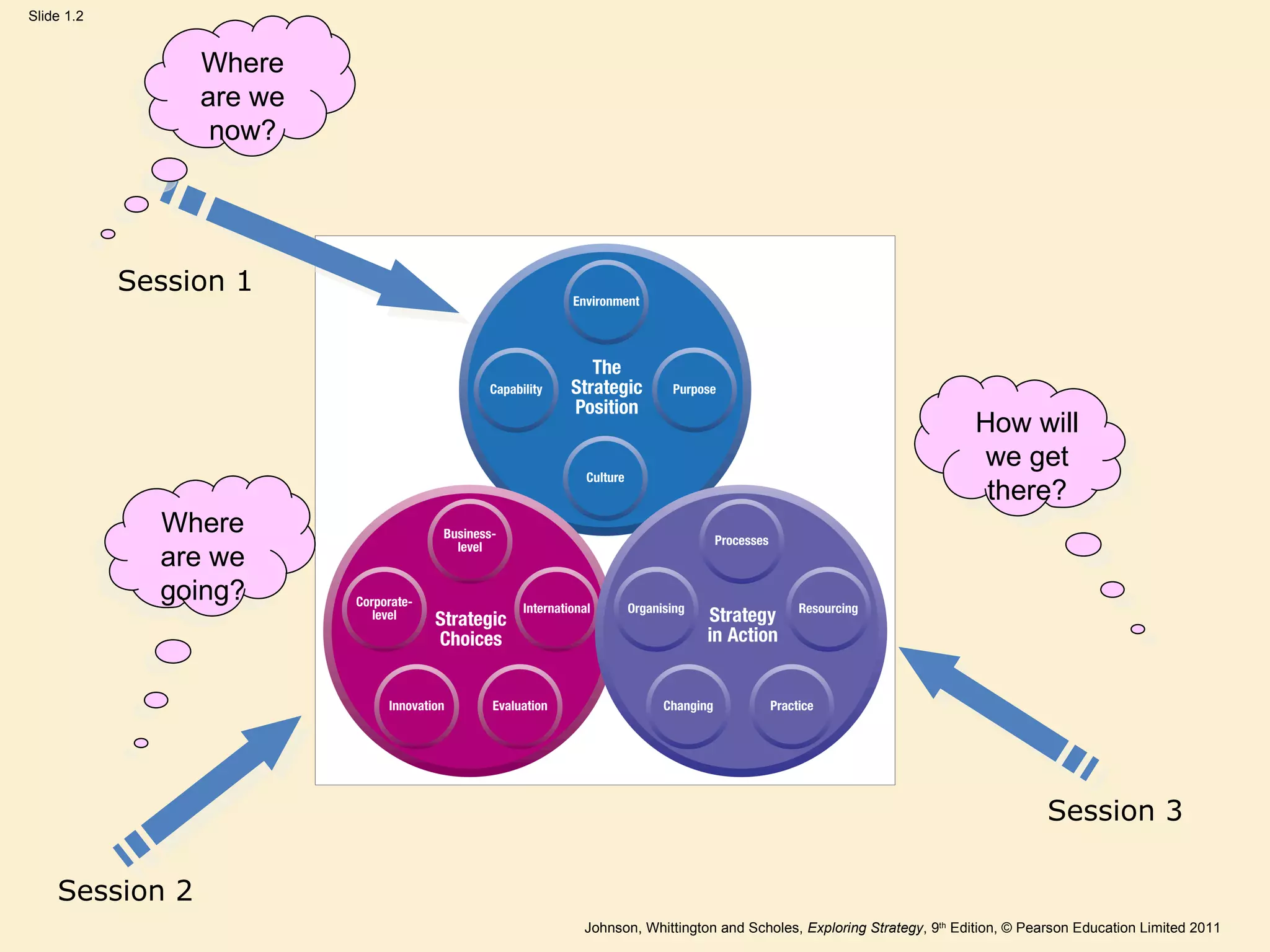

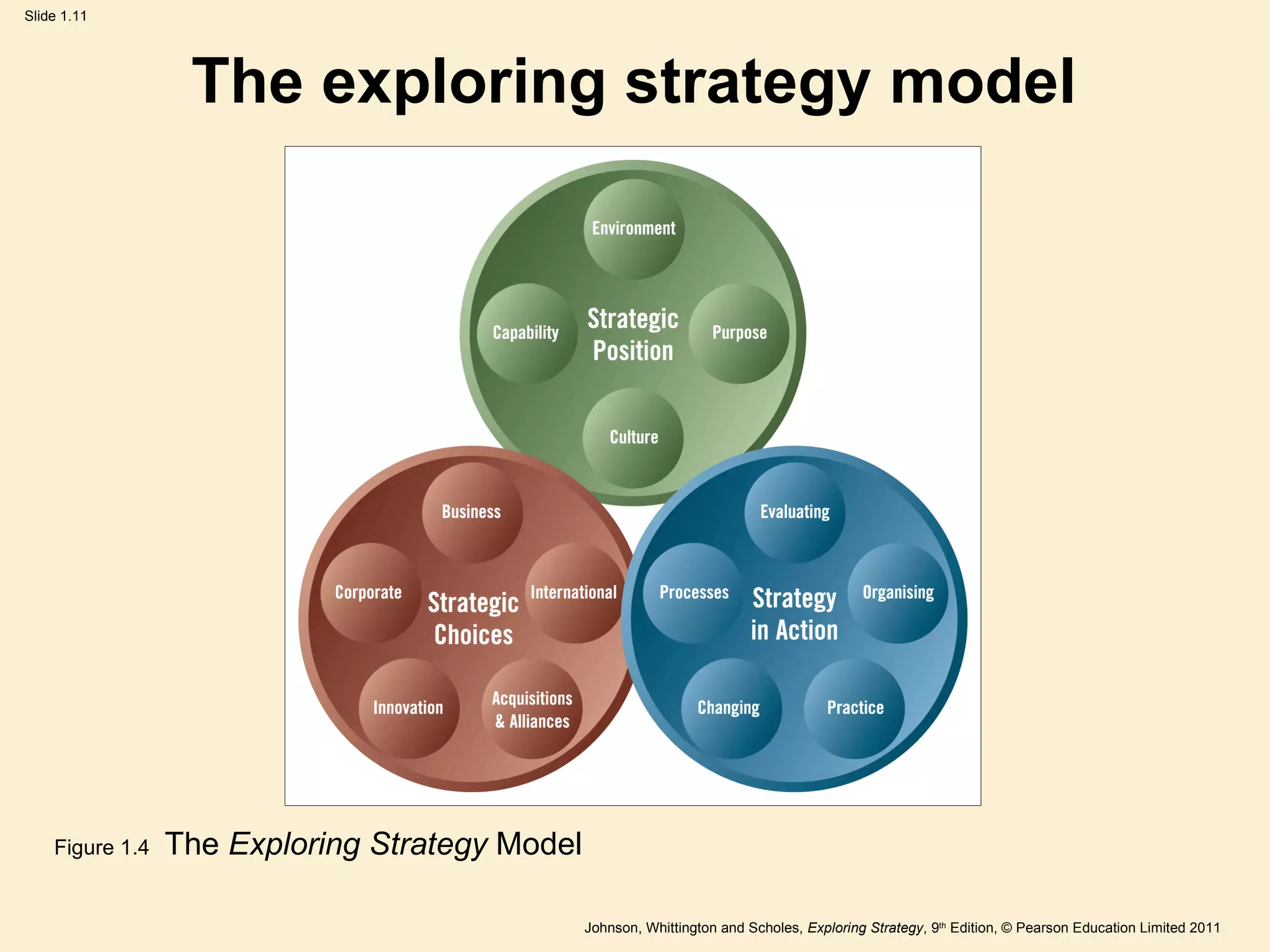

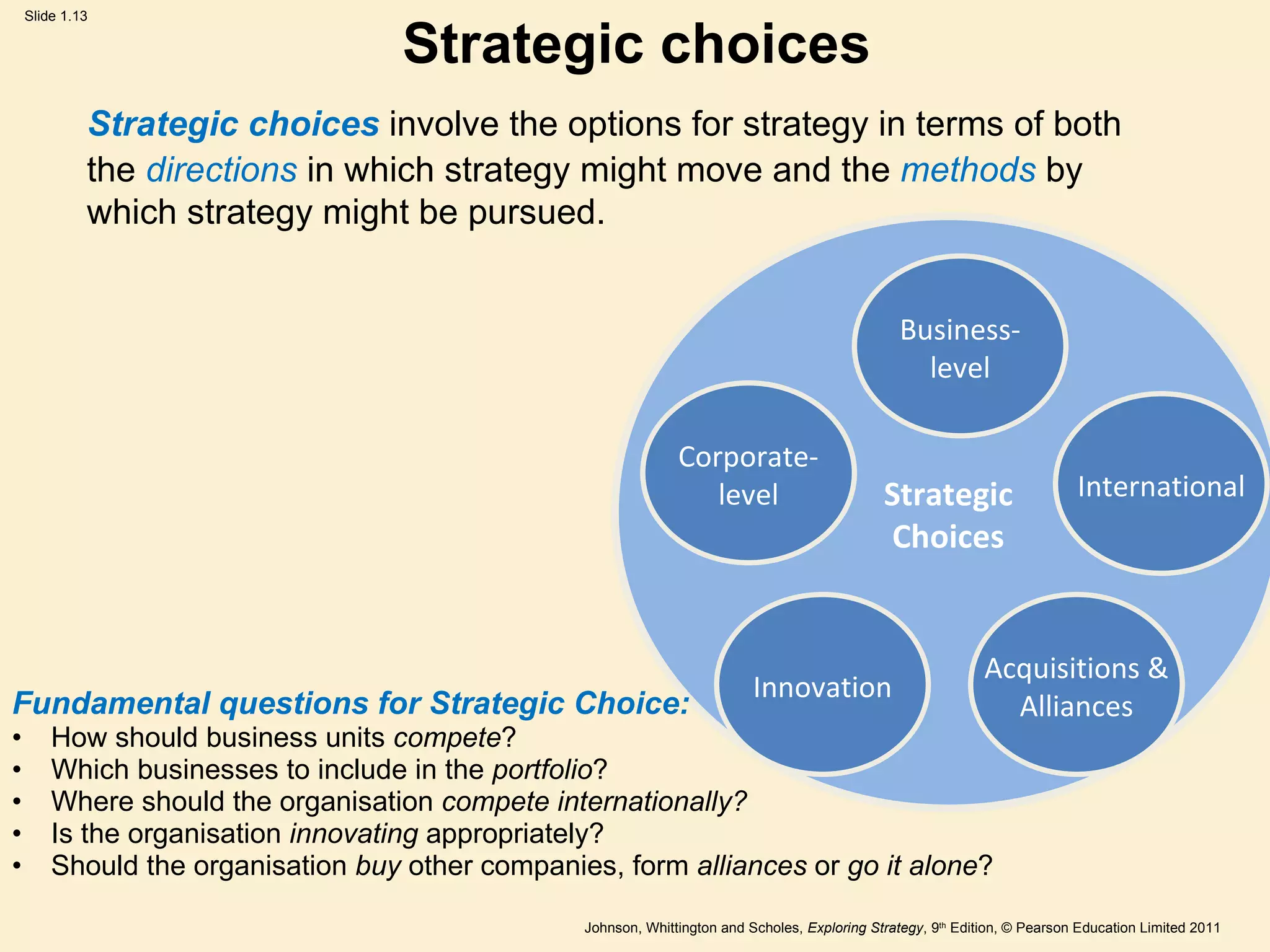

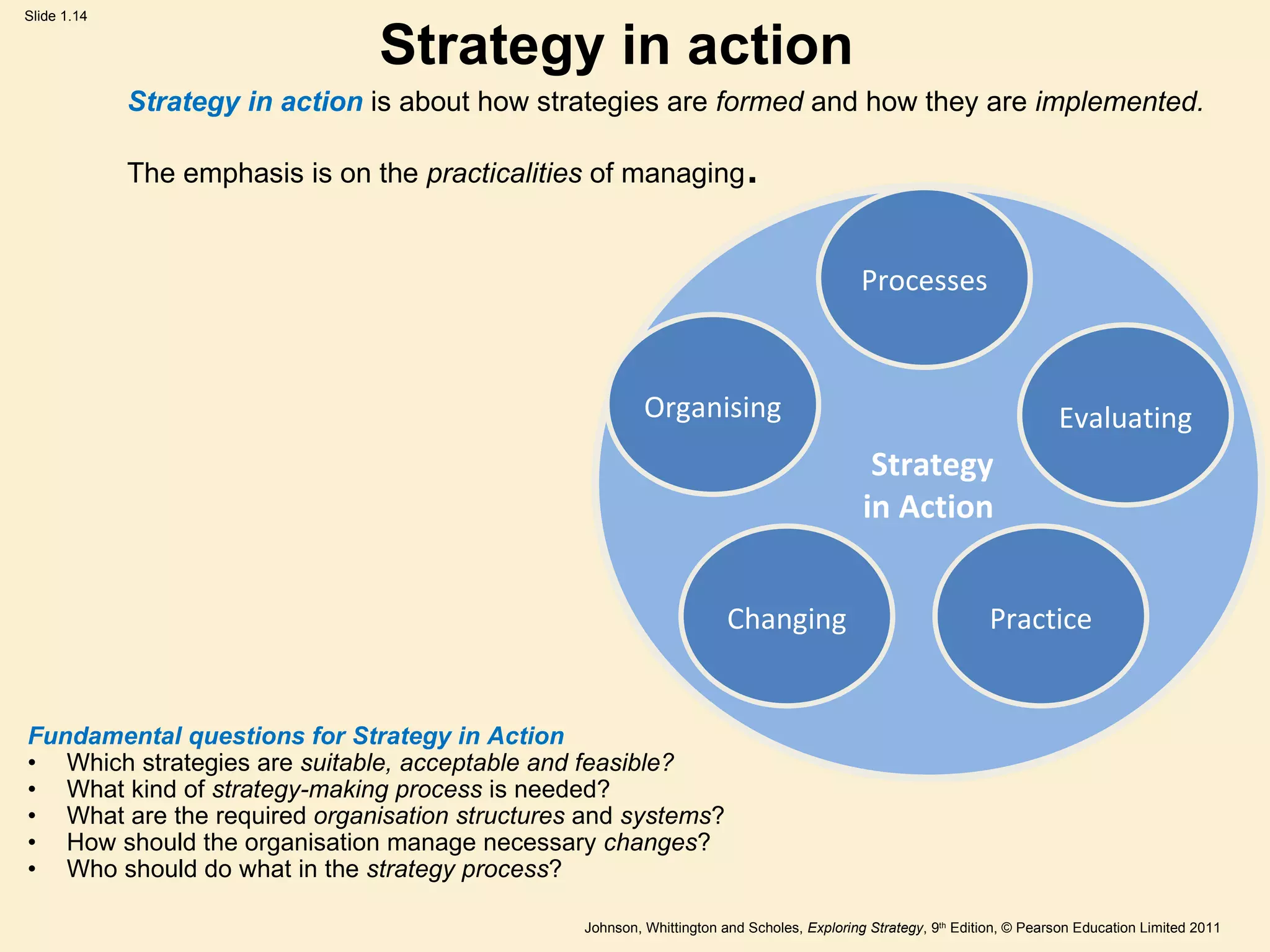

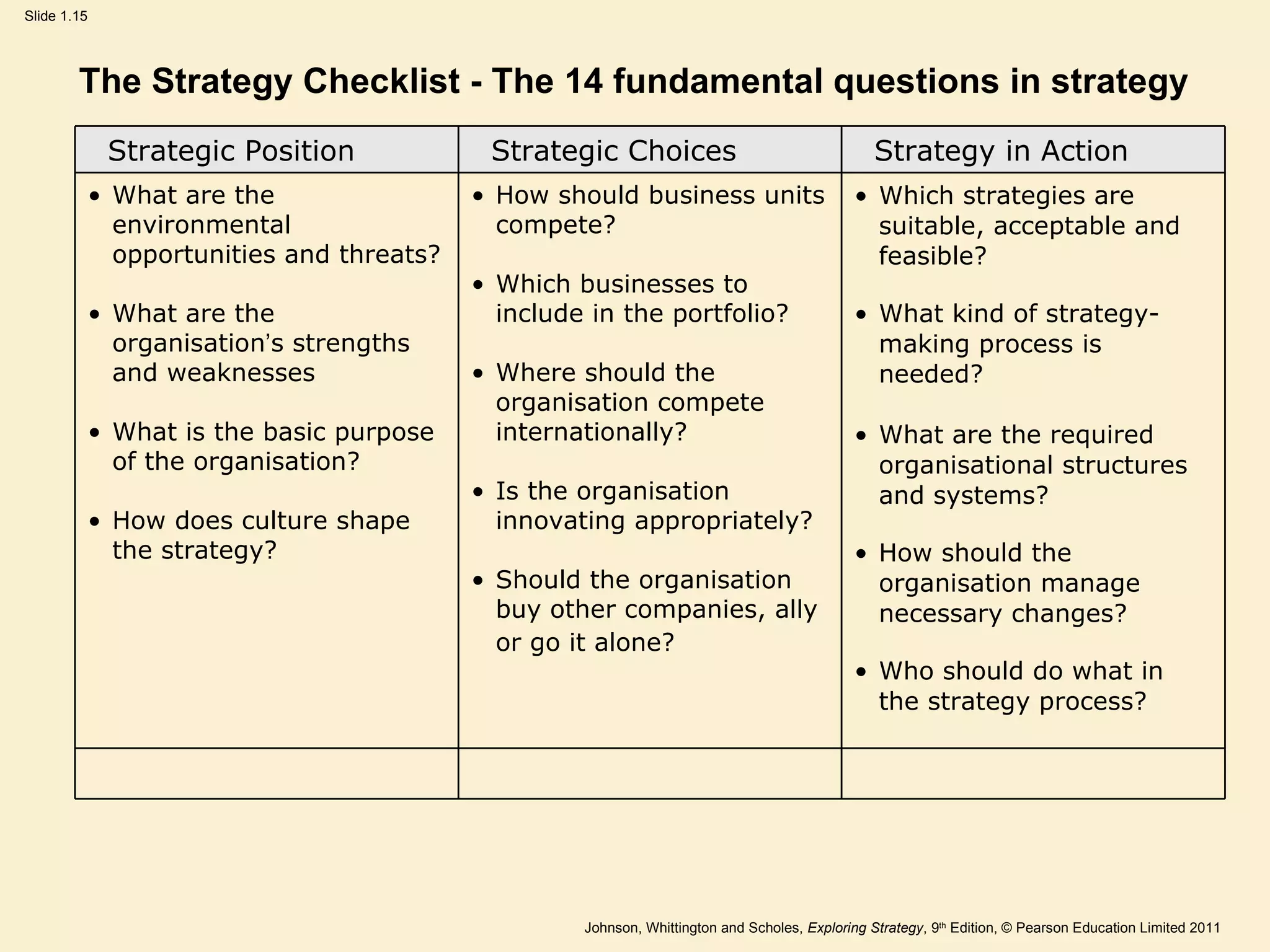

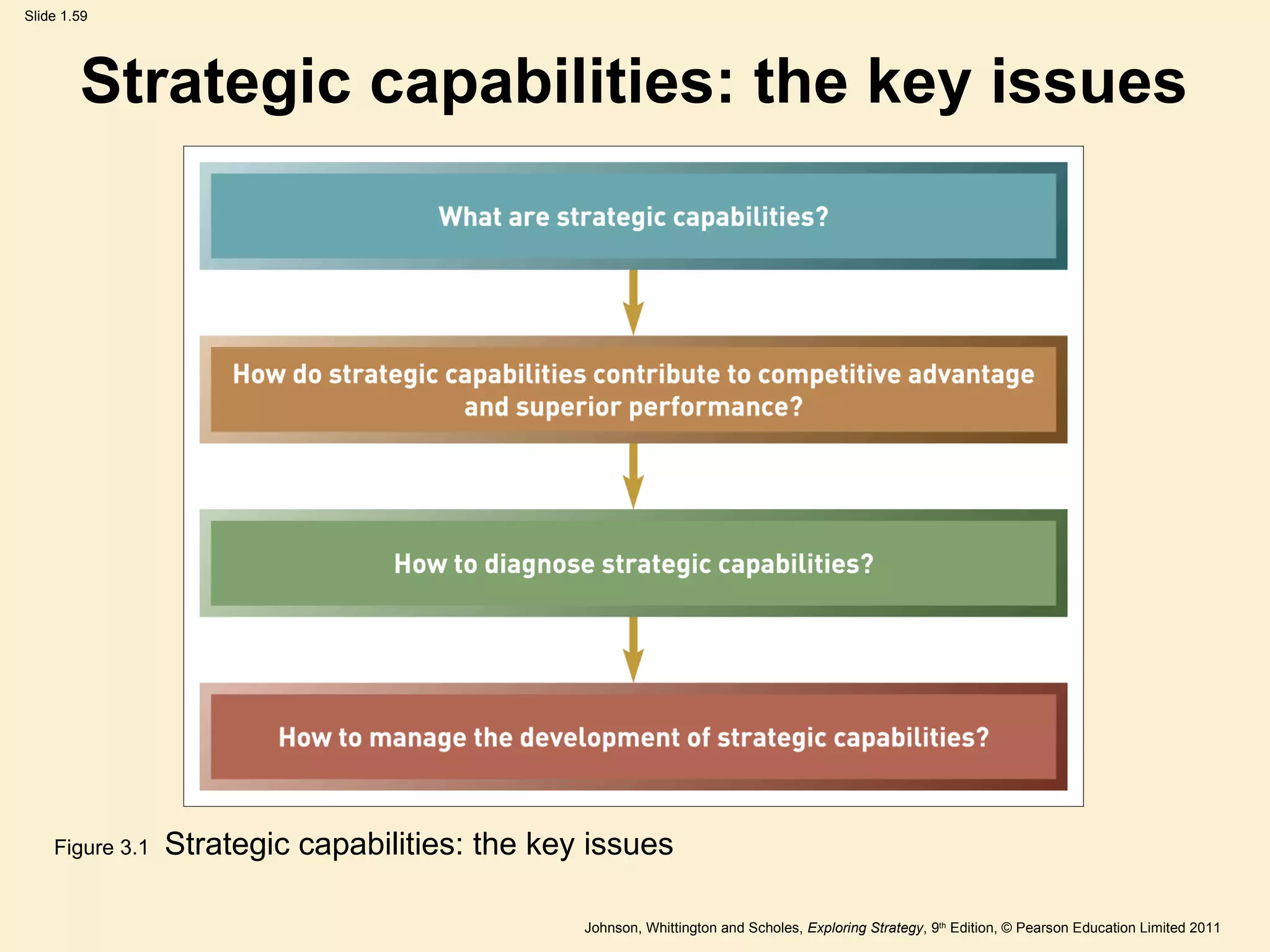

1. The document discusses strategy at different levels of an organization, including corporate, business, and operational strategies. It introduces the Exploring Strategy model for analyzing an organization's strategic position, strategic choices, and strategy in action.

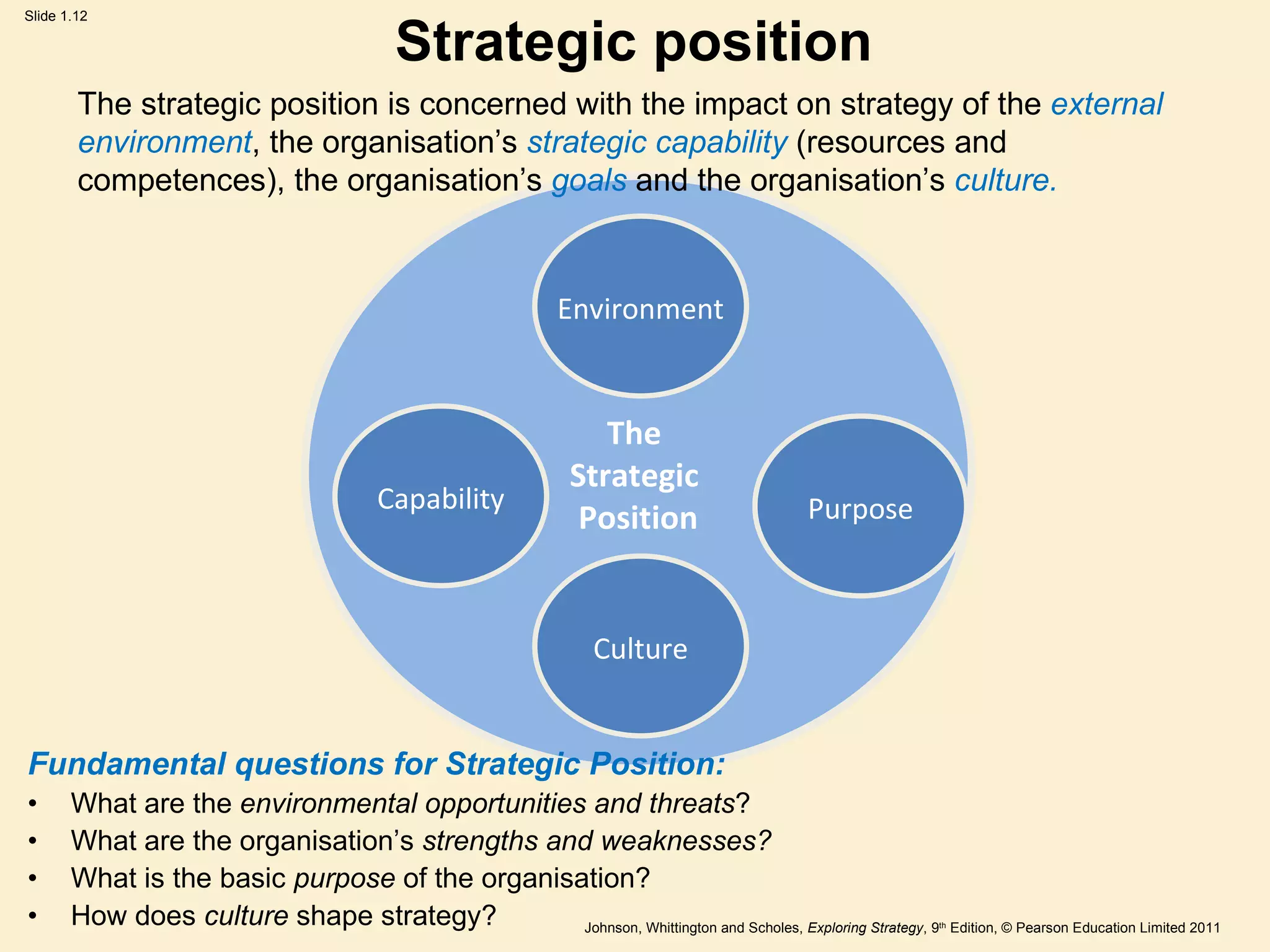

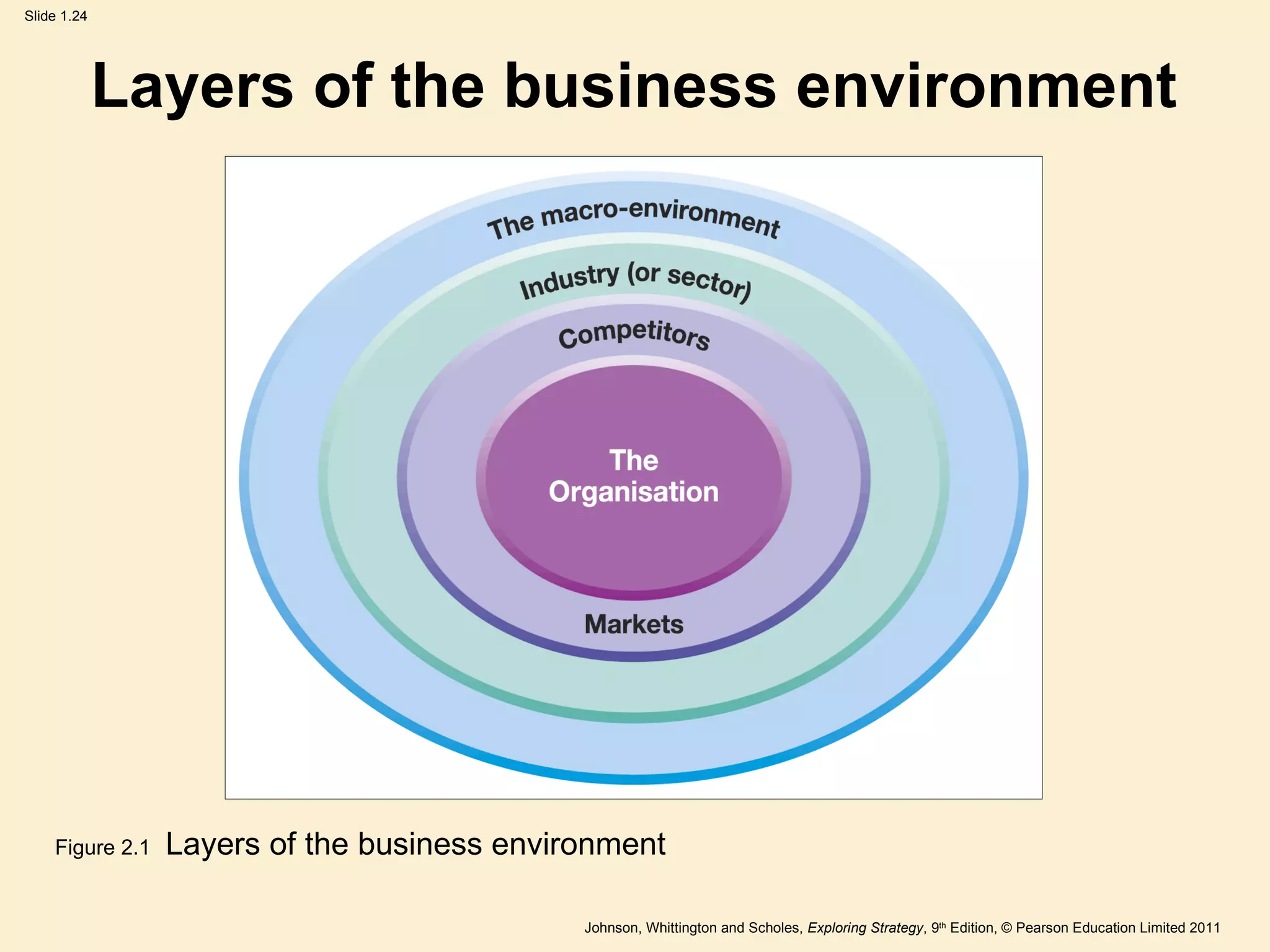

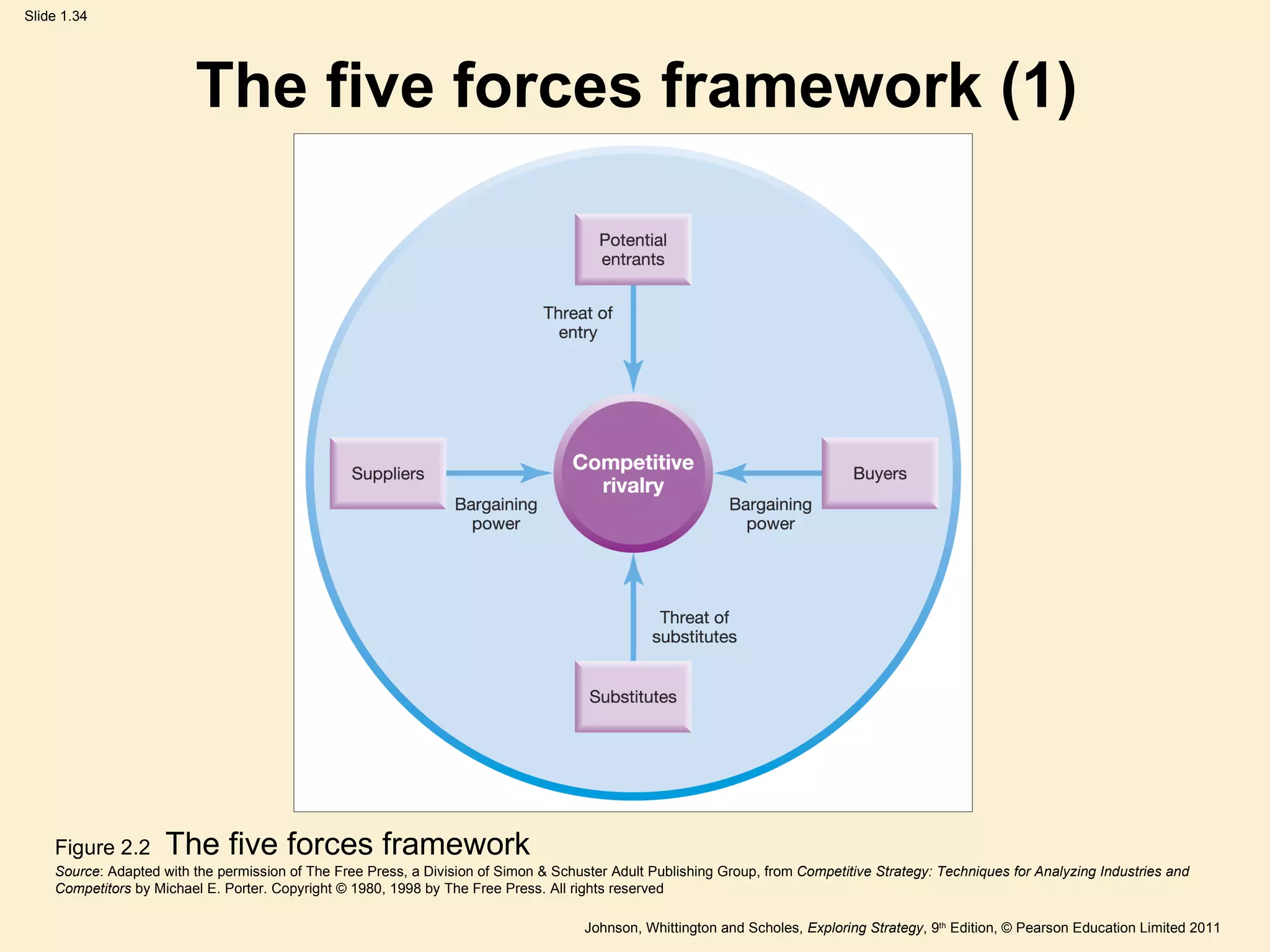

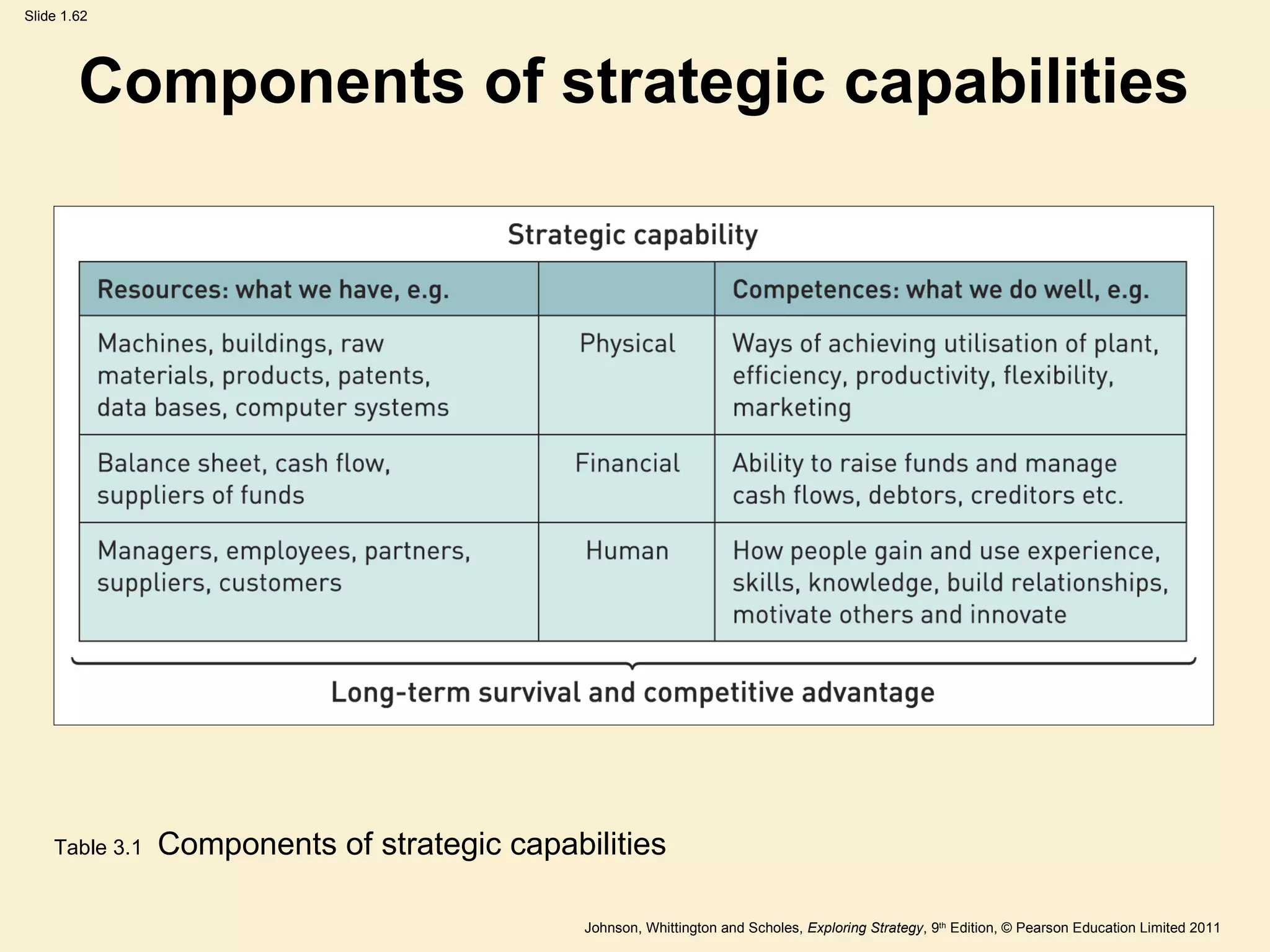

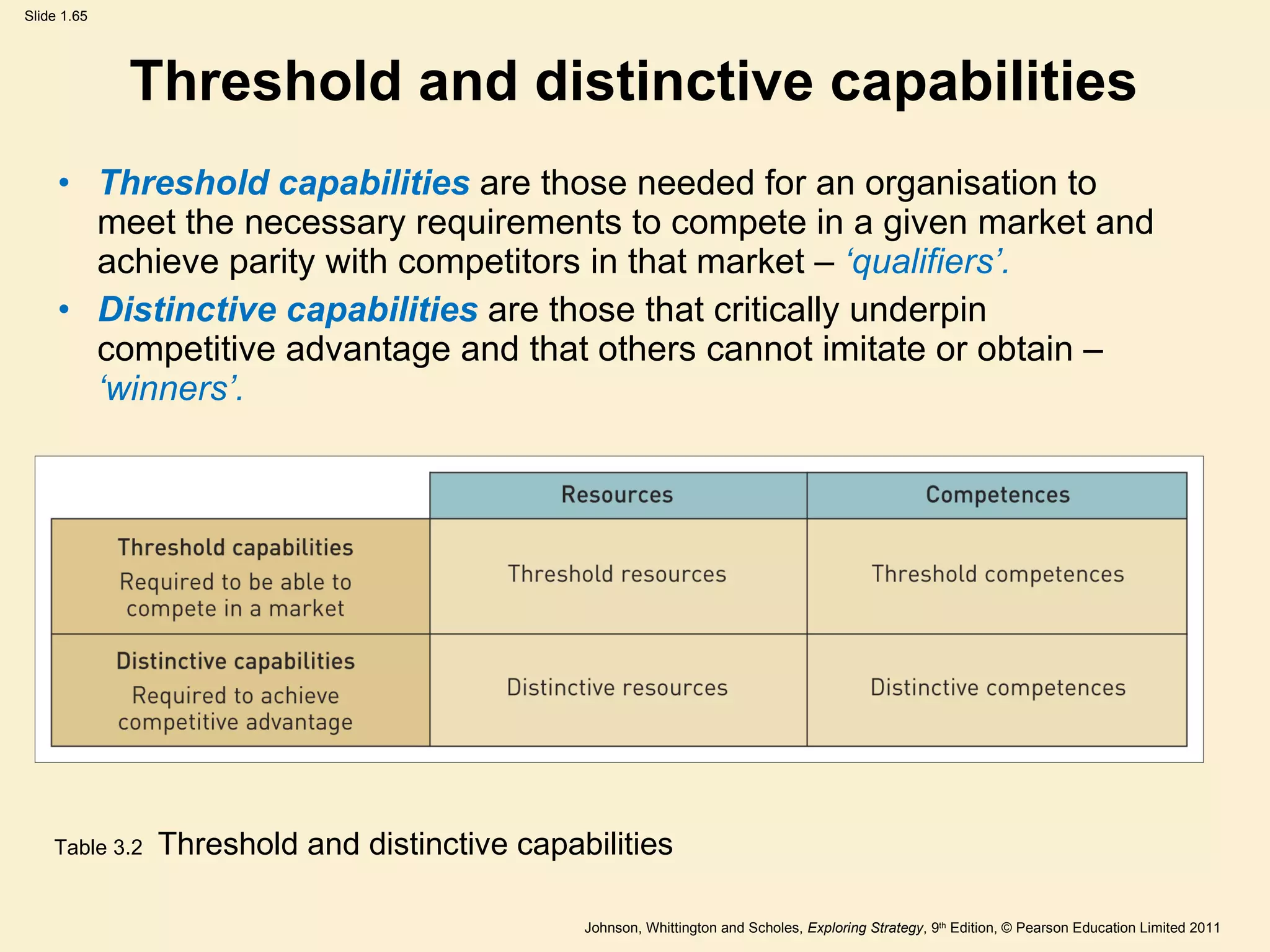

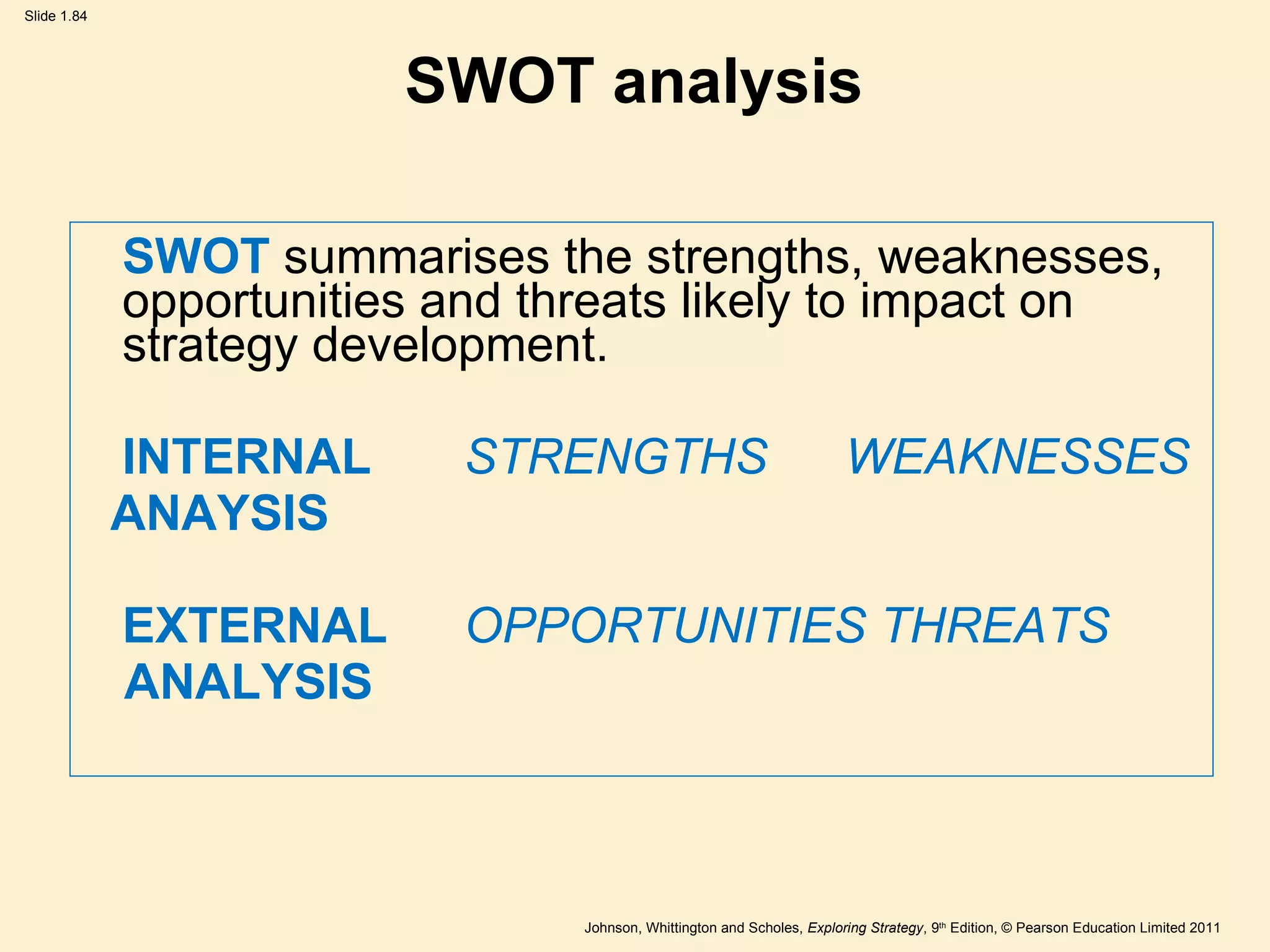

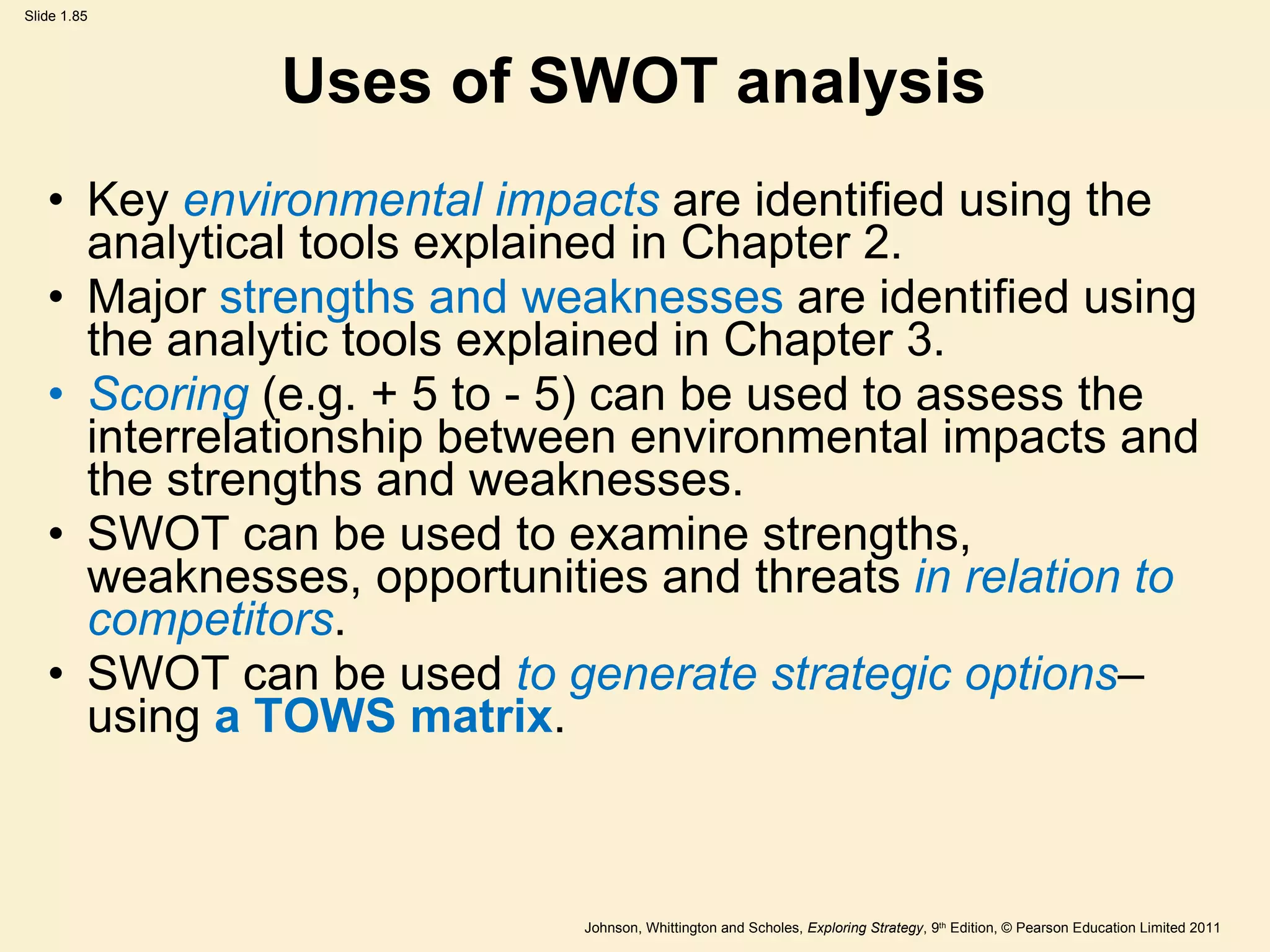

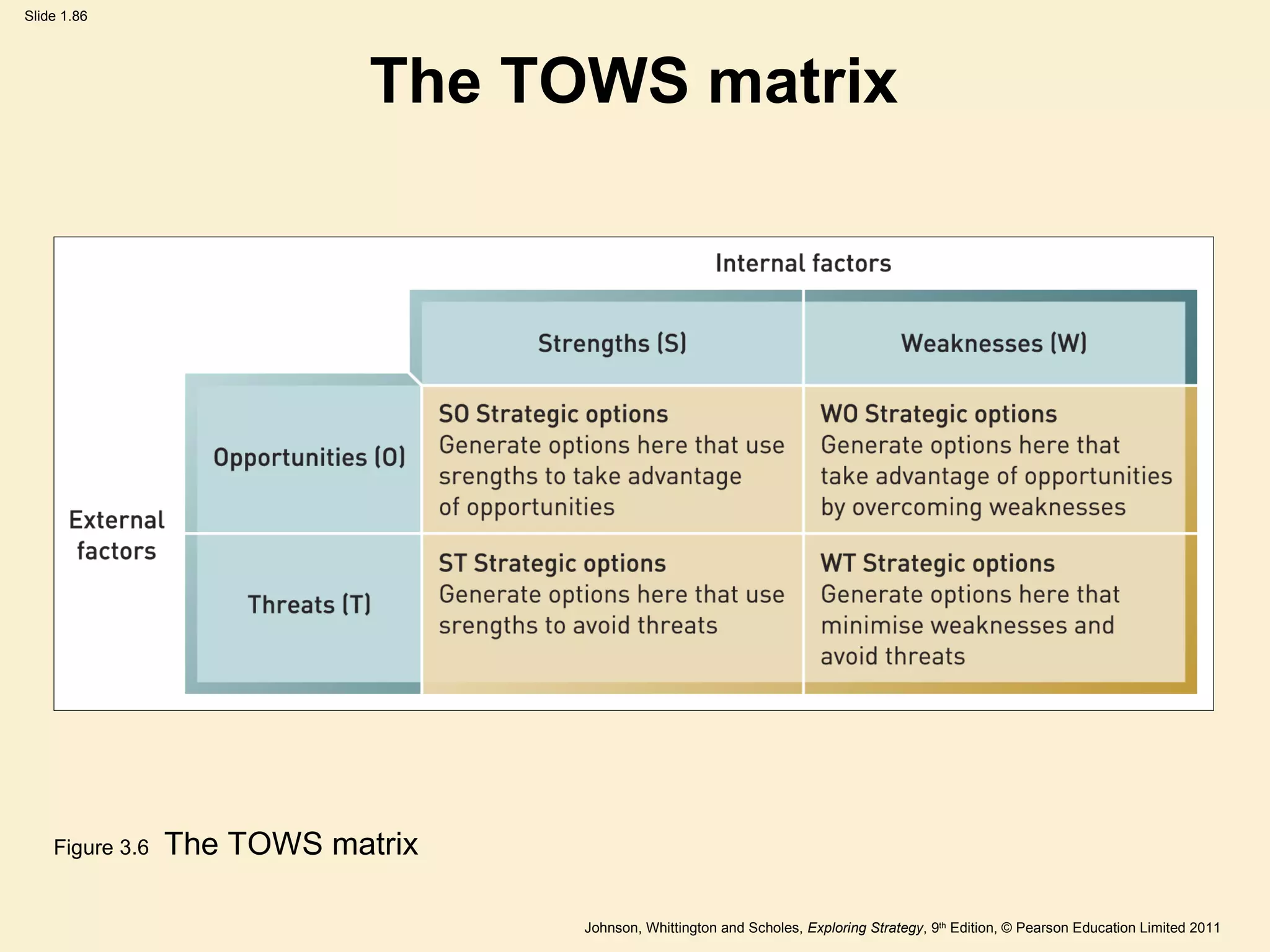

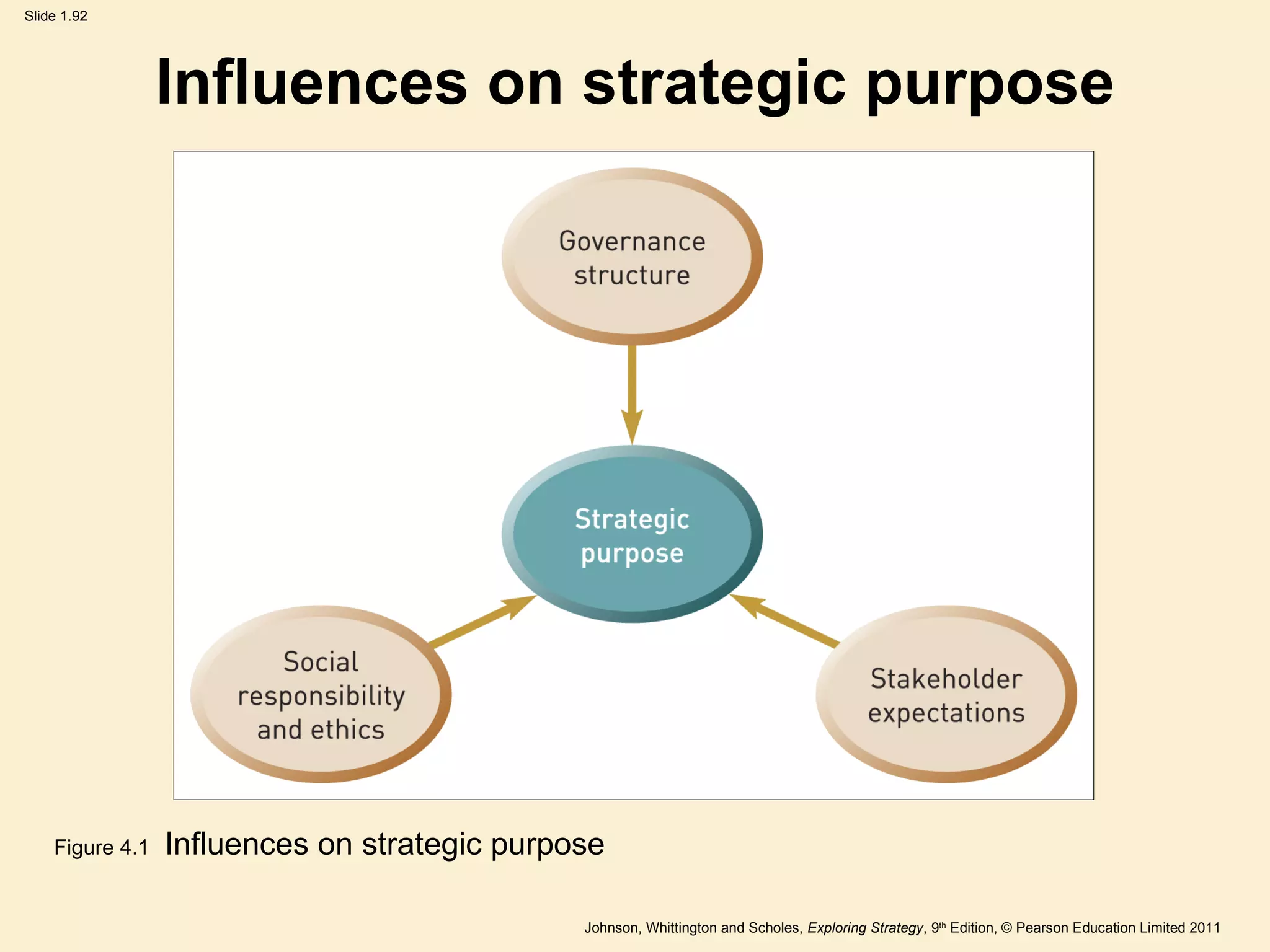

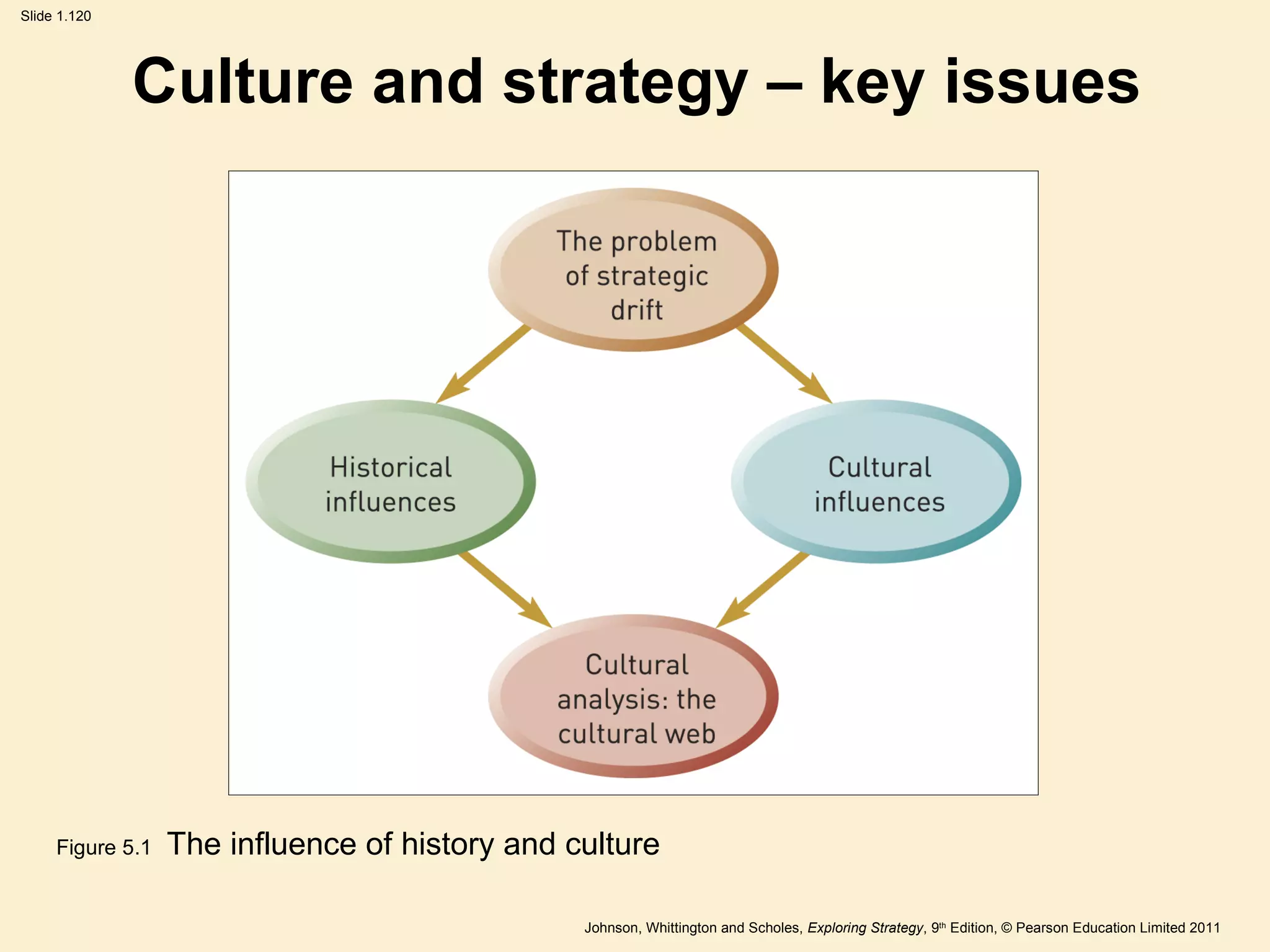

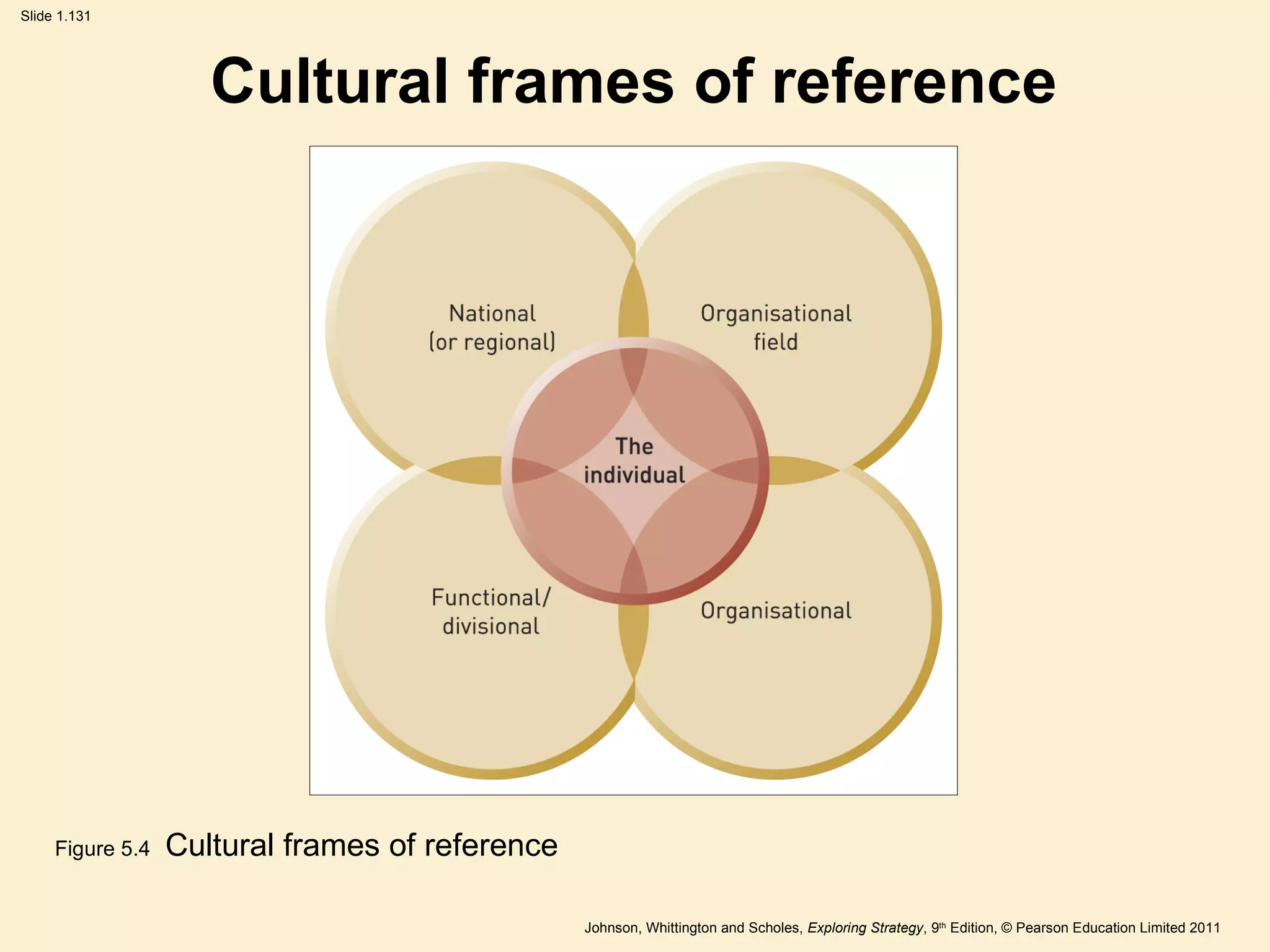

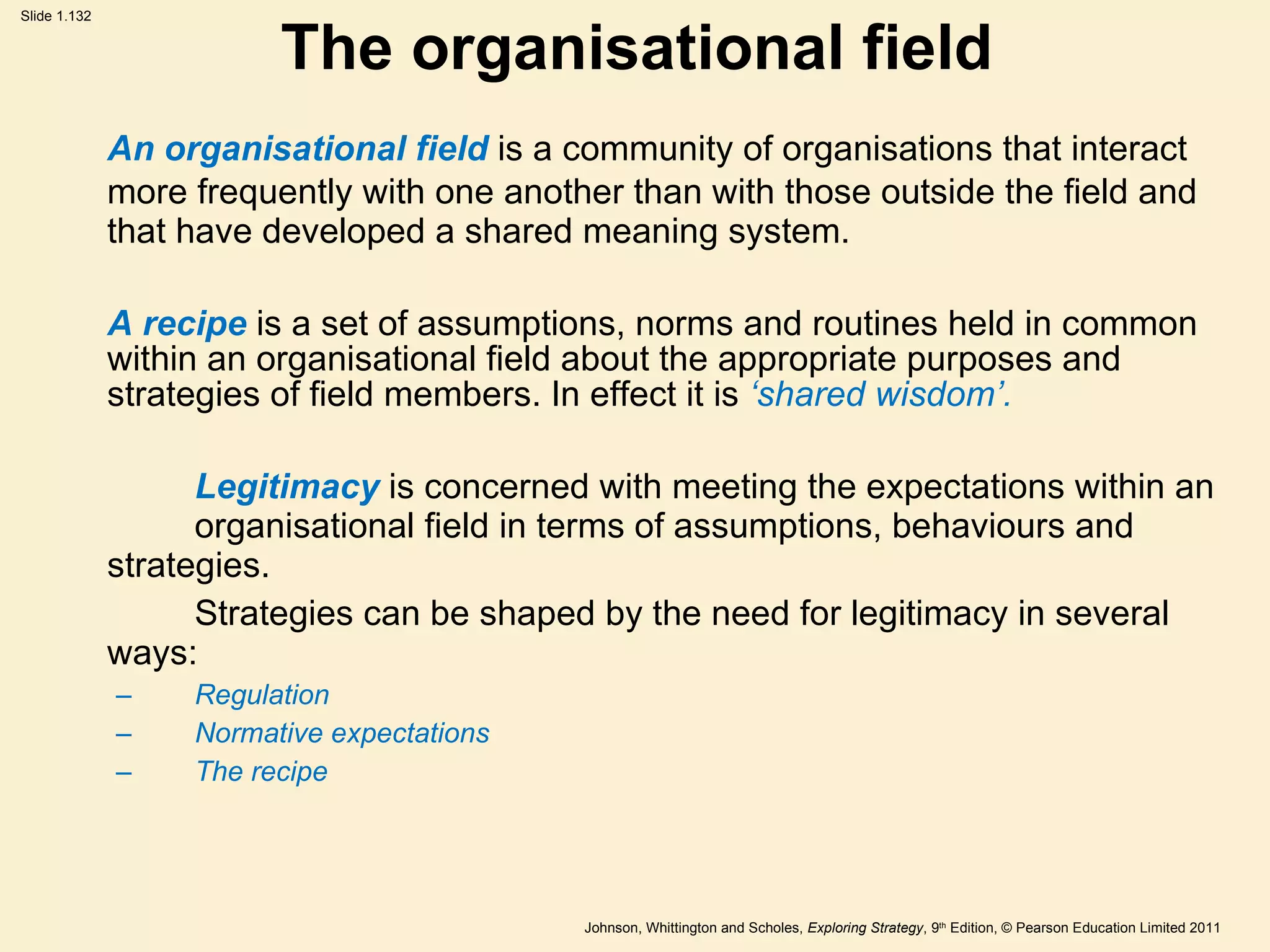

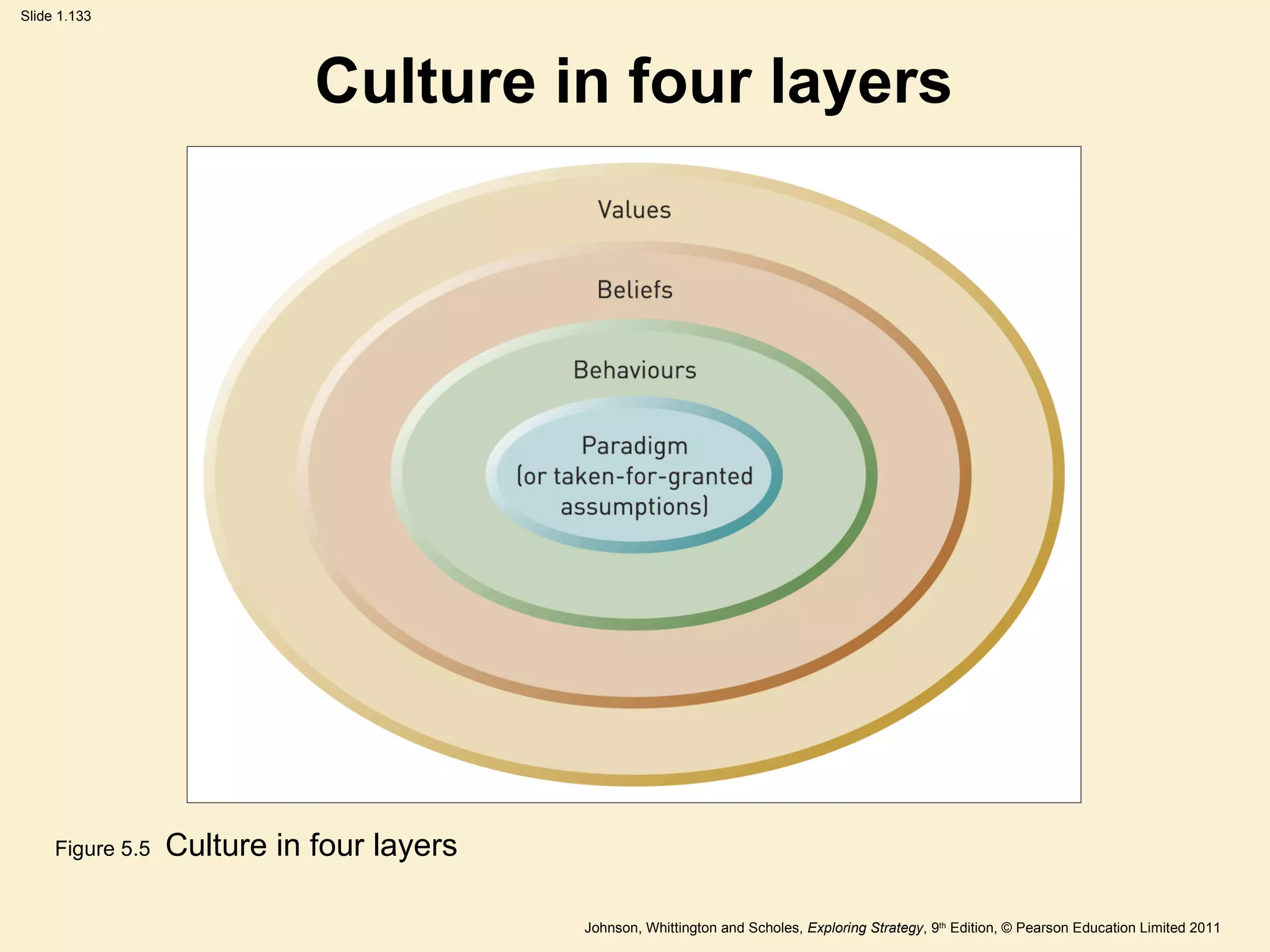

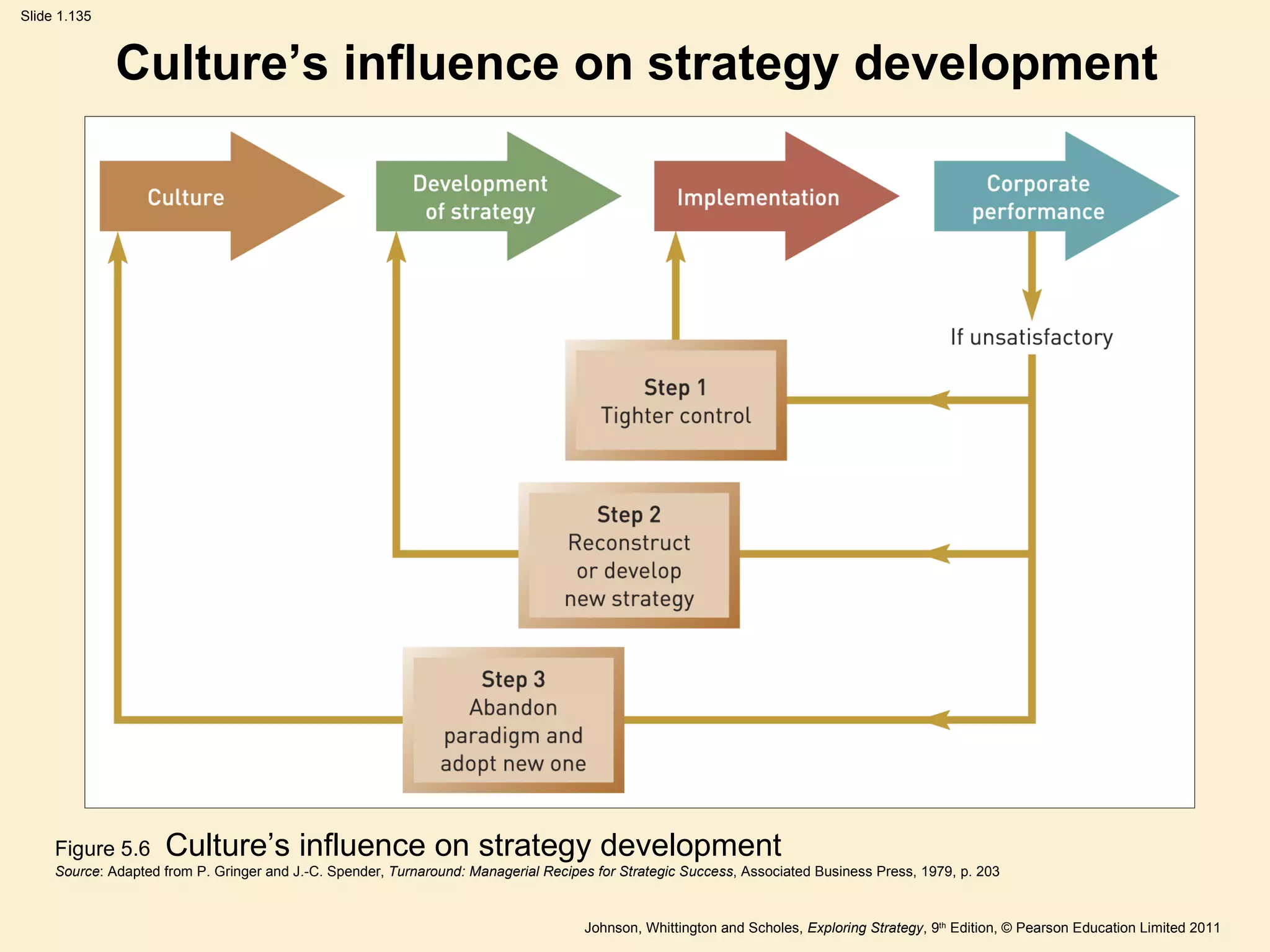

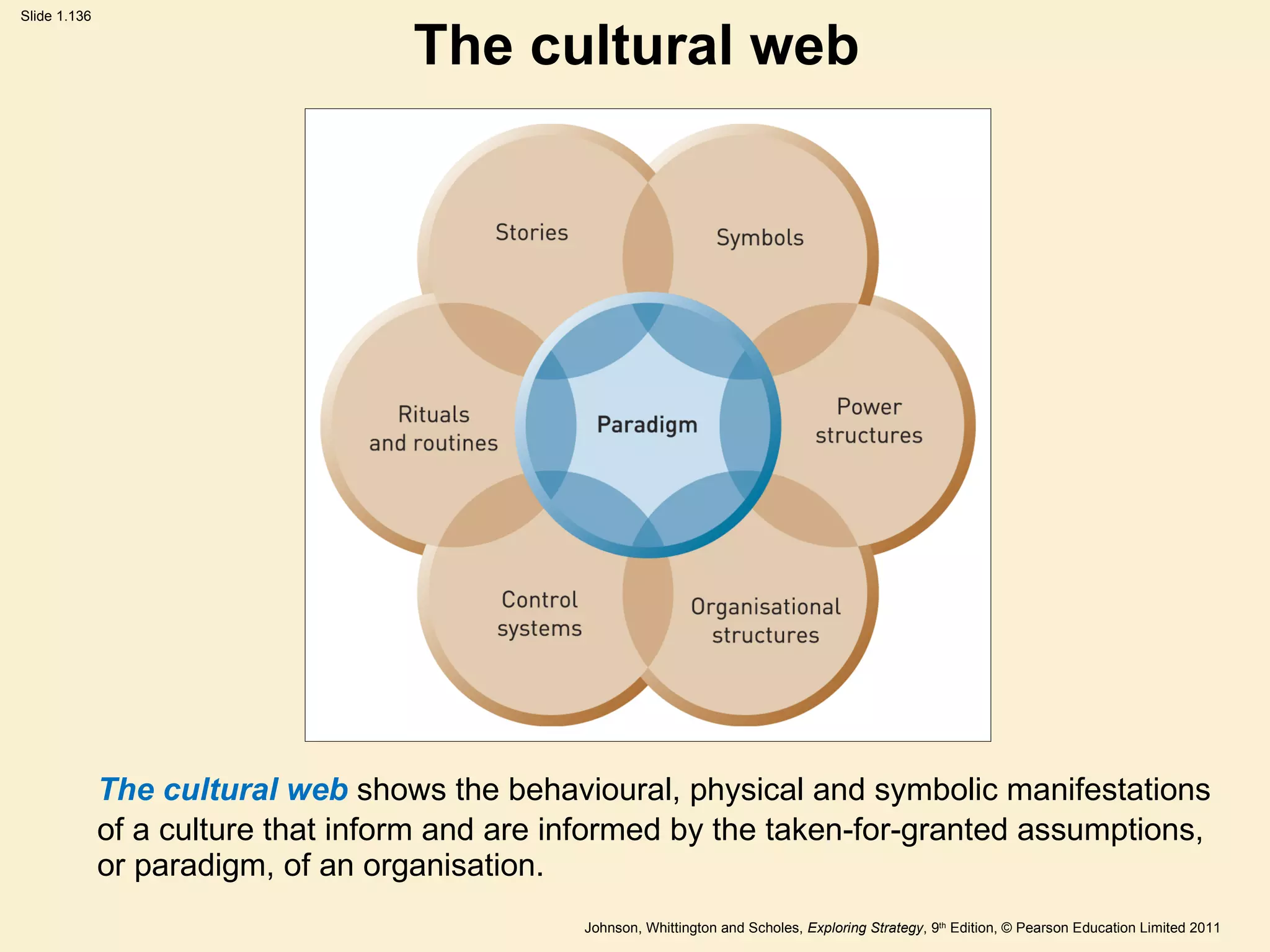

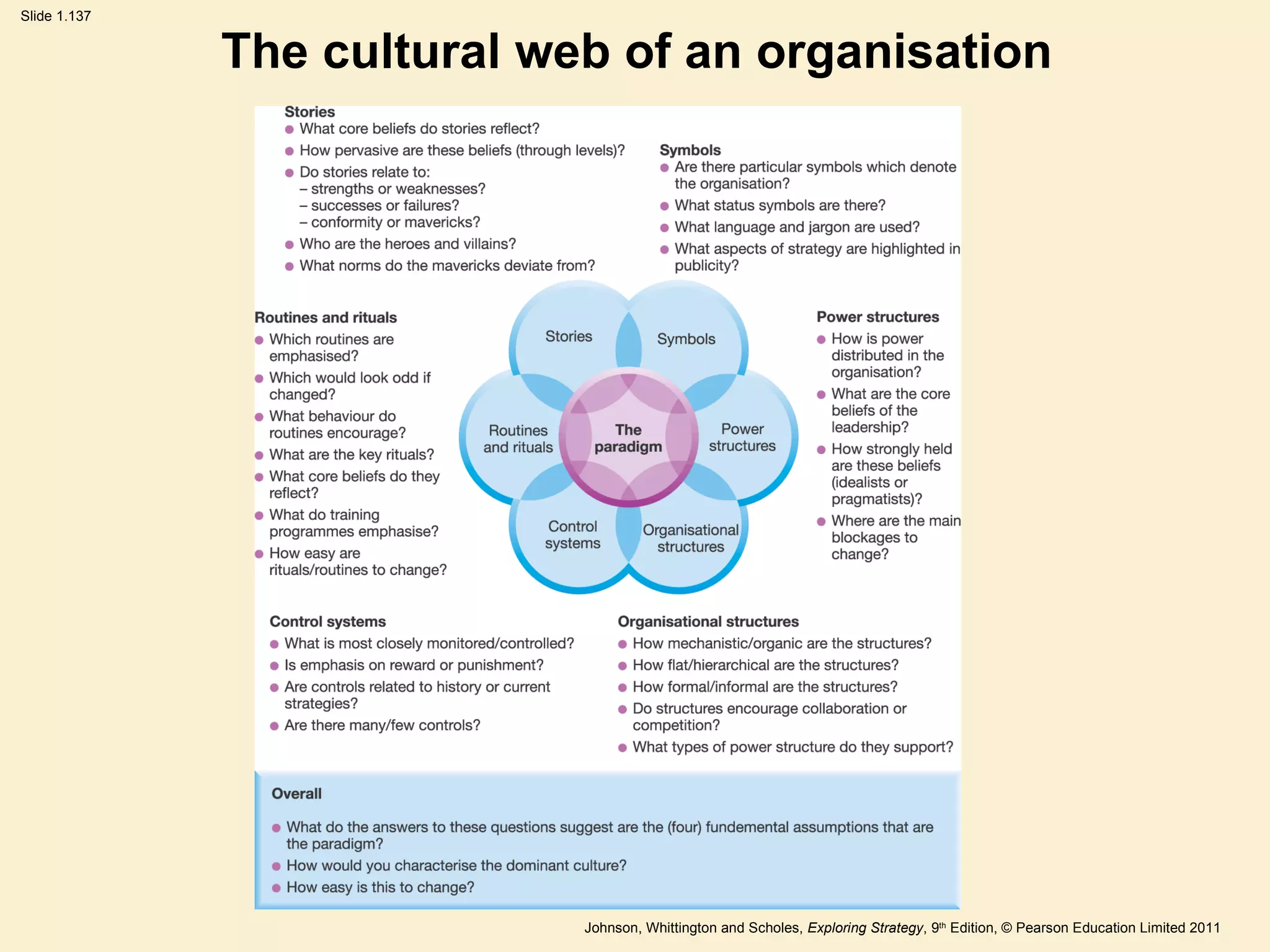

2. The Exploring Strategy model examines the external environment, internal capabilities and resources, organizational culture and purpose, and helps identify threats, opportunities, strengths, and weaknesses.

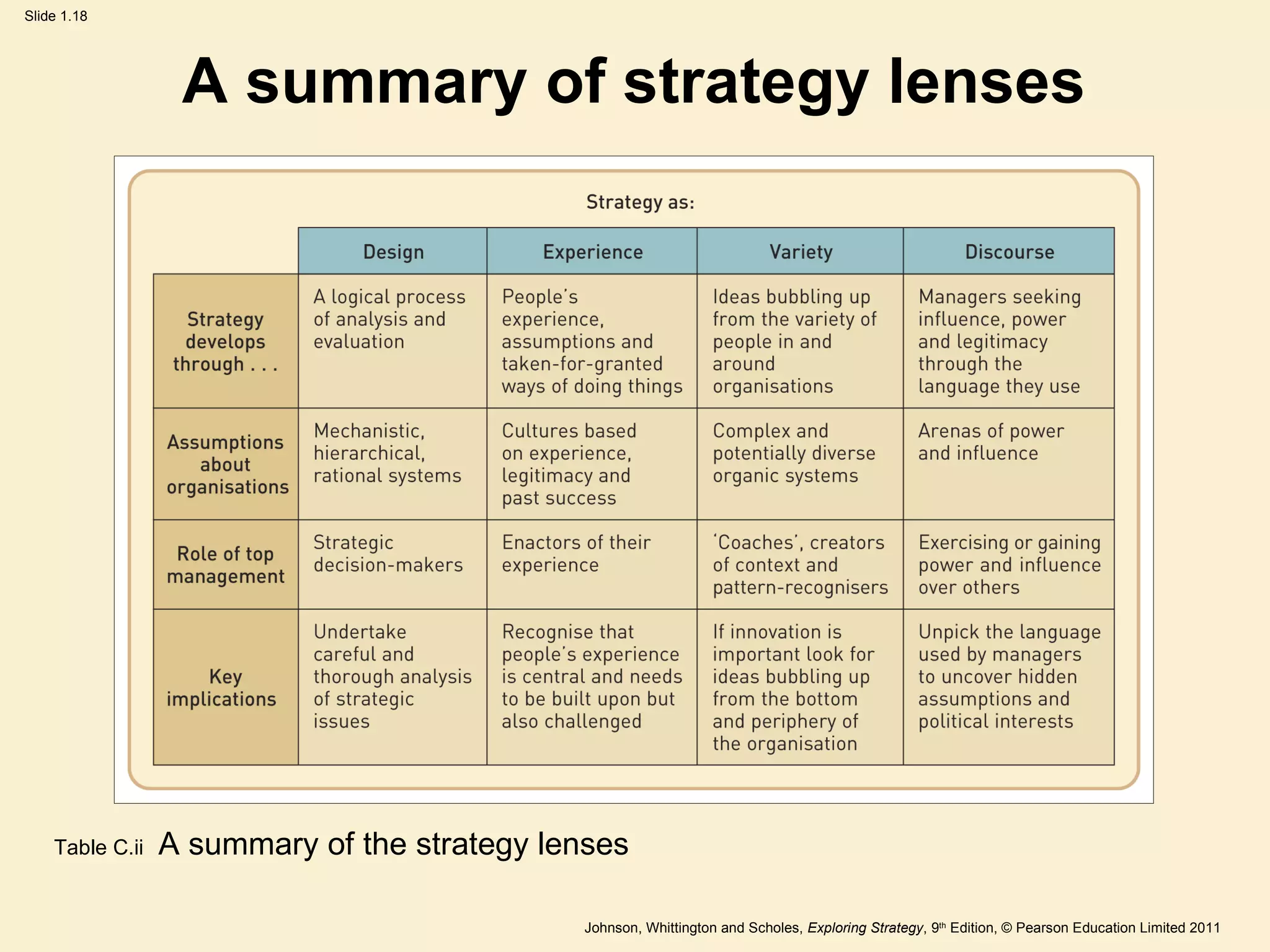

3. Strategic issues can be viewed through different lenses like design, experience, variety, and discourse to generate new insights for strategy analysis.