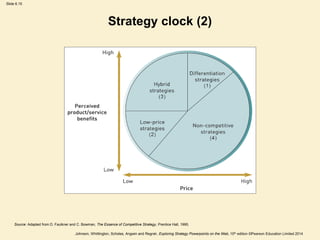

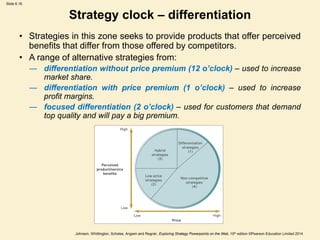

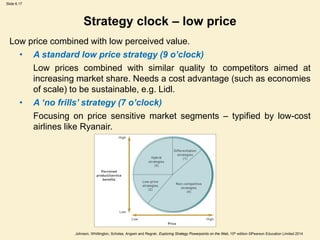

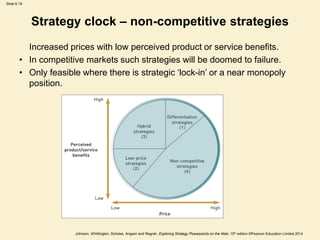

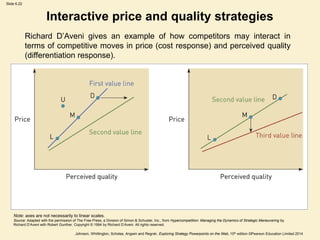

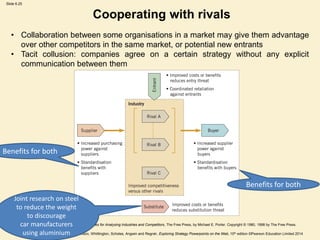

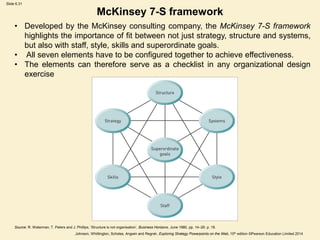

The document outlines various strategic choices and generic strategies that companies can pursue, including cost leadership, differentiation, and focus strategies. It discusses frameworks for analyzing strategies, such as Porter's generic strategies, the strategy clock, and interactive strategies where competitors respond to one another's moves. Game theory and scenarios like the prisoner's dilemma are presented as ways to analyze competitive interactions and strategic interdependence between firms.