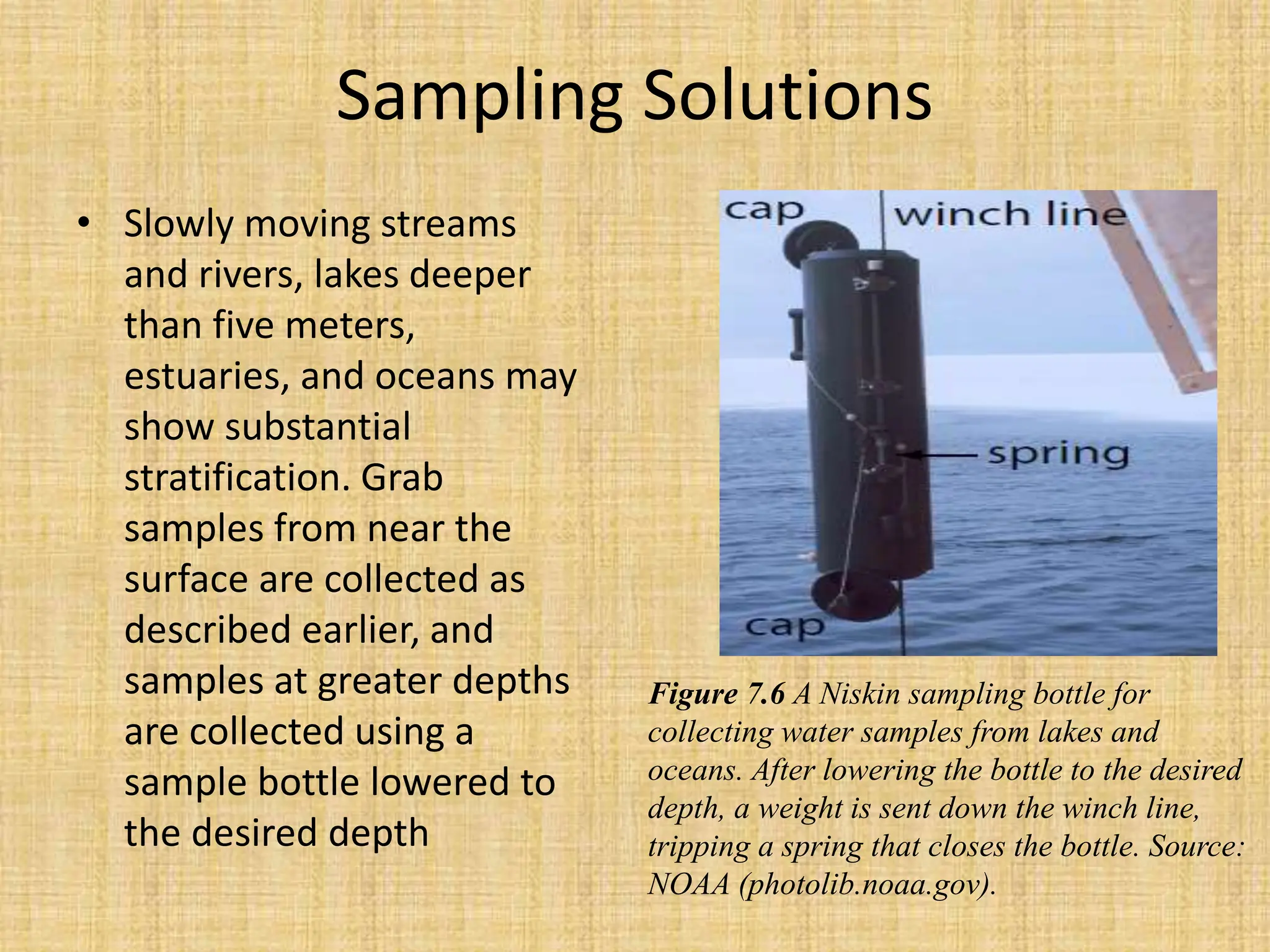

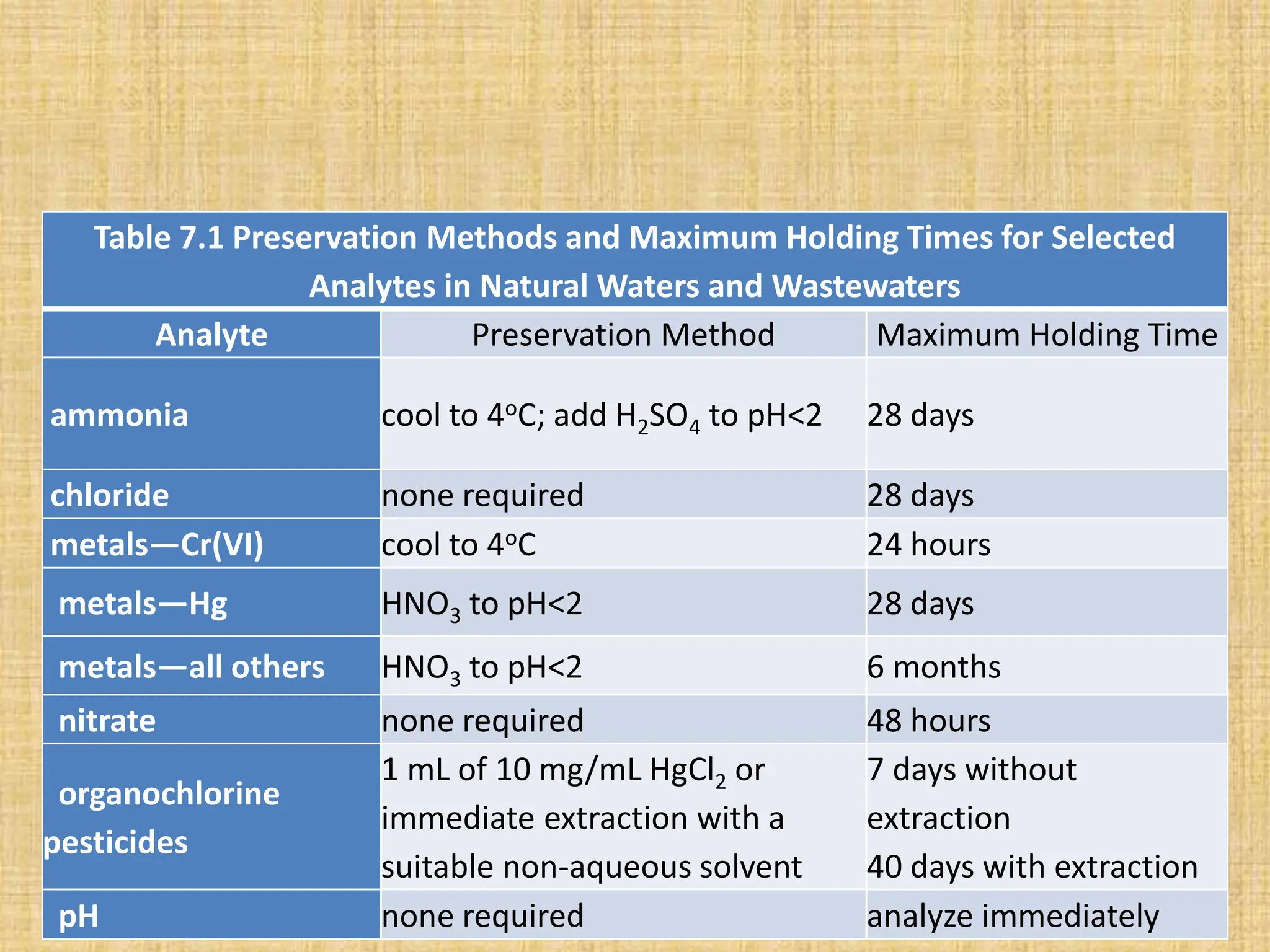

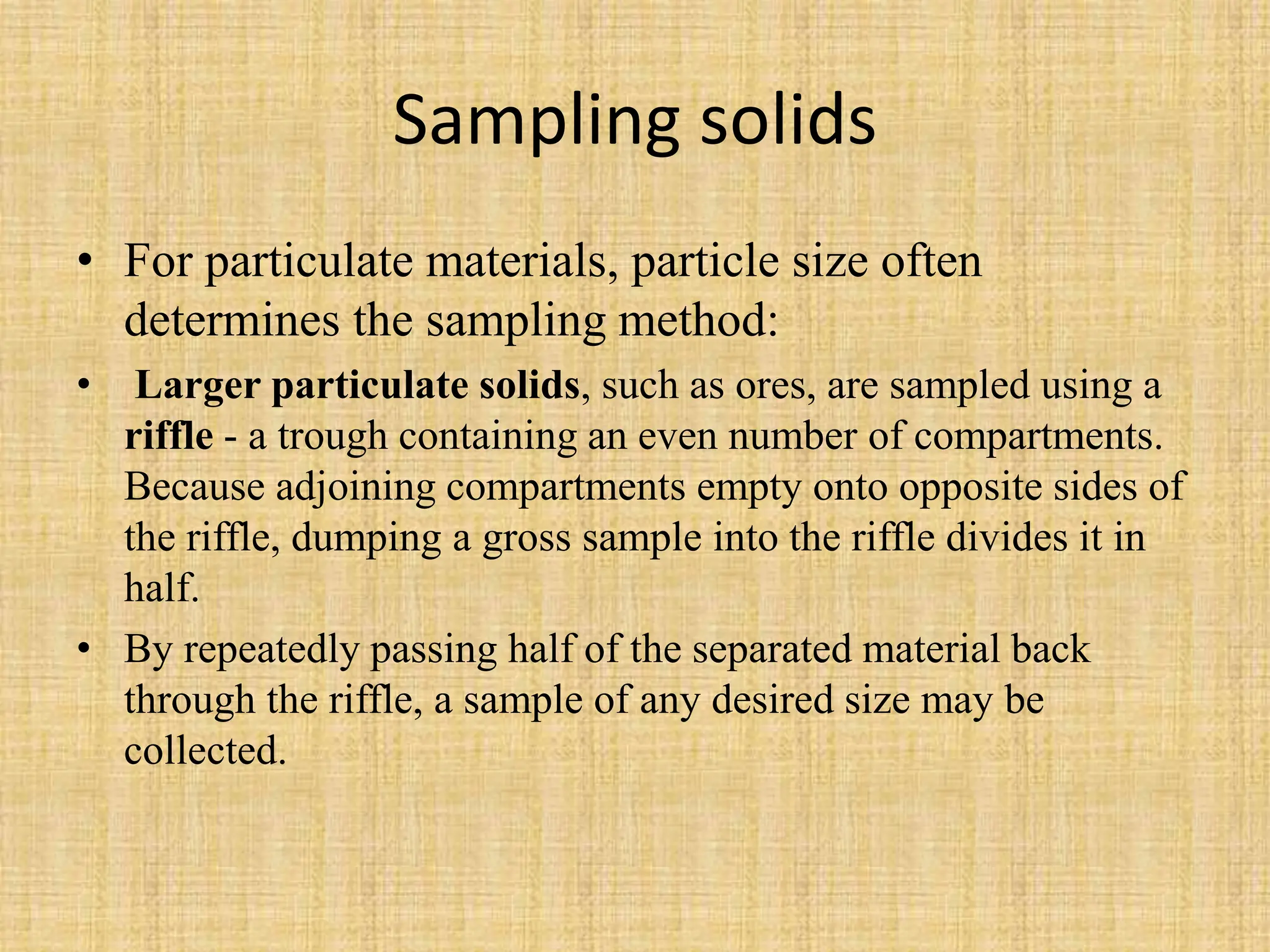

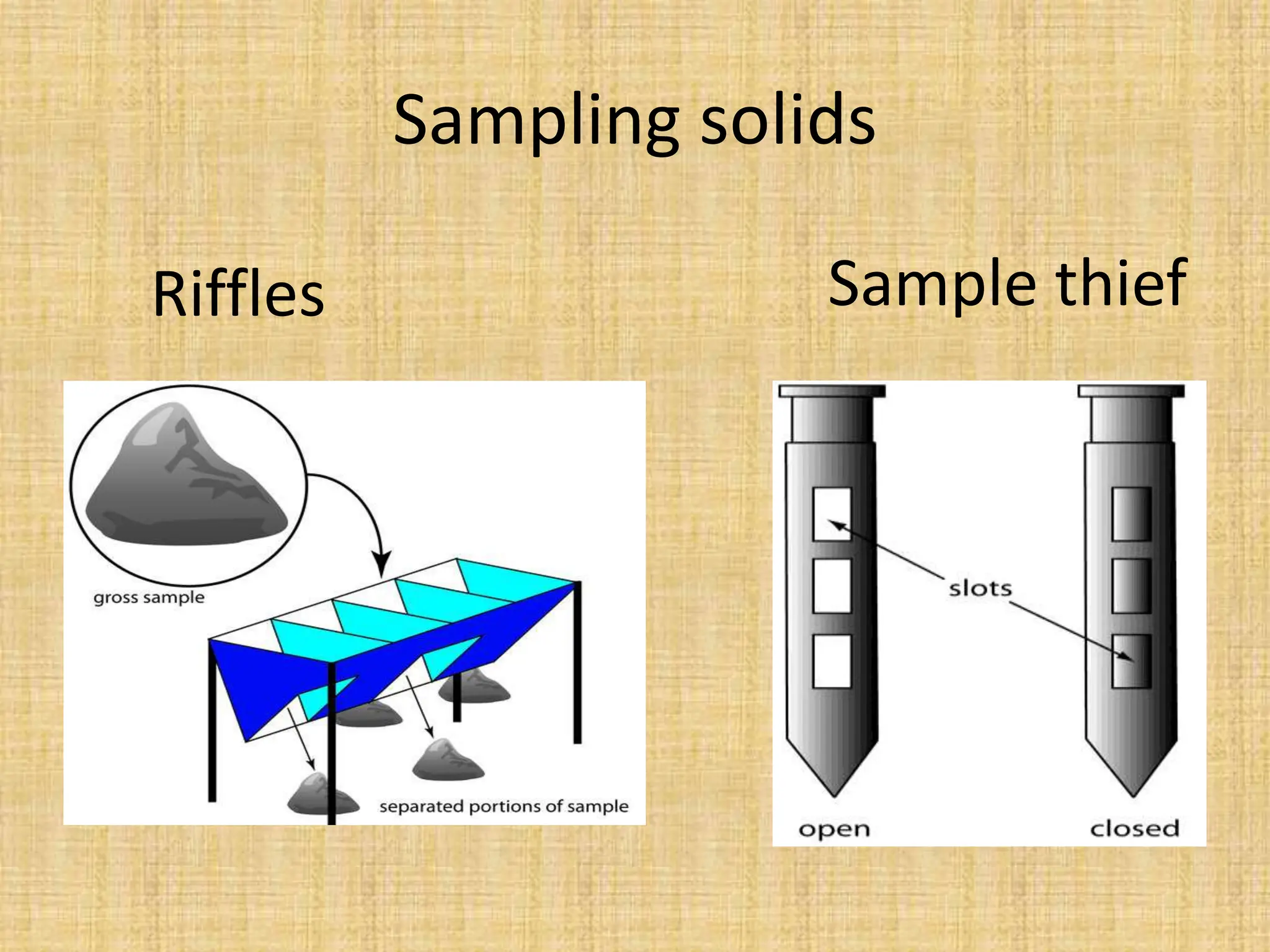

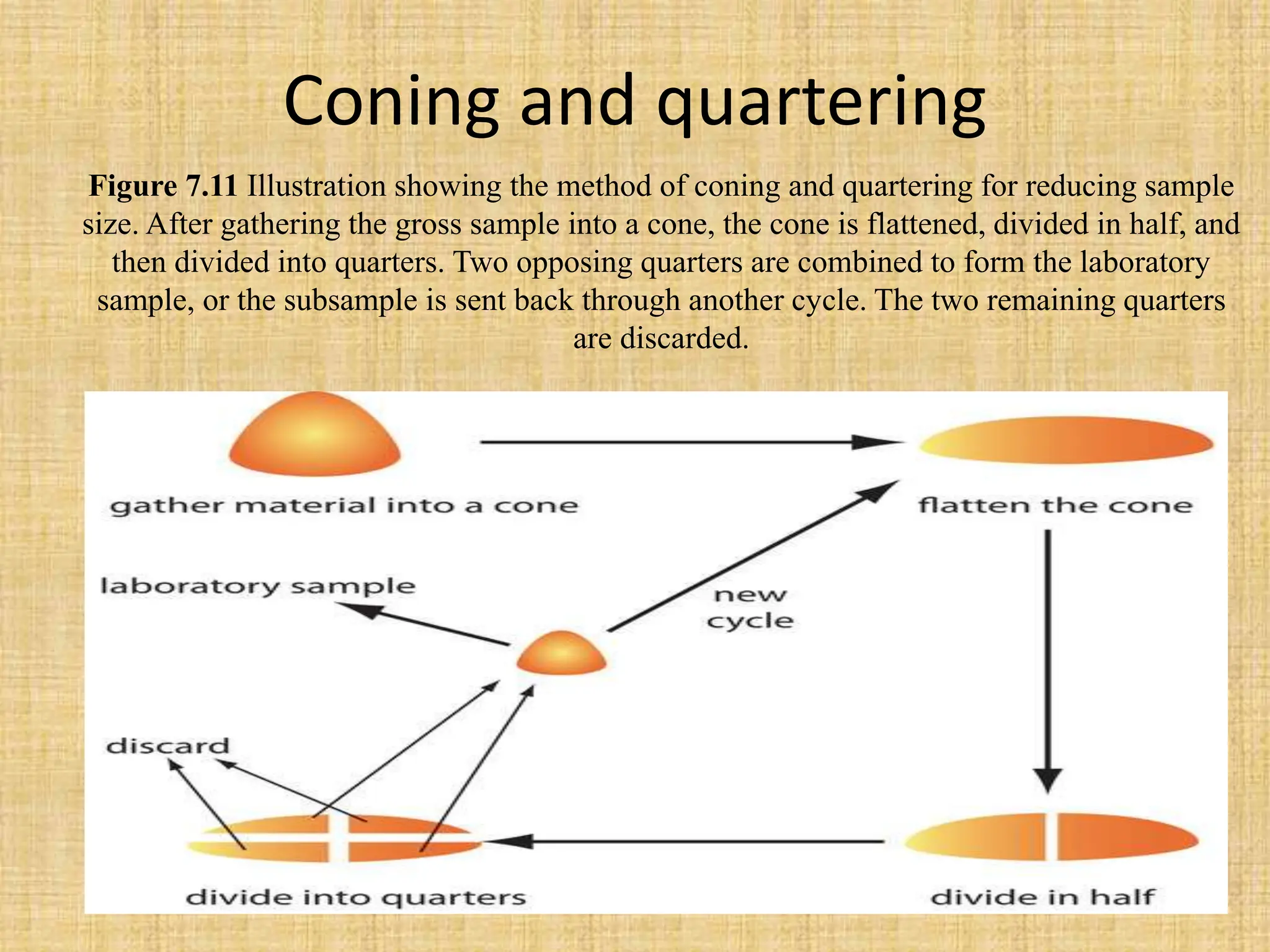

The document provides an in-depth overview of sampling in analytical chemistry, defining it as the process of obtaining a representative portion of a substance from a larger bulk. It discusses various types of samples, techniques for collection and preservation, the importance of a well-structured sampling plan, and methods for minimizing sampling errors. Additionally, it covers sample preparation and analysis, highlighting the importance of controlling conditions to ensure accurate results.